DEVELOPING AN OPEN ECONOMY ENTREPRENEURS, INSTITUTIONS AND FOREIGN TRADE IN NORWAY'S TRANSFORMATION 1845-1975

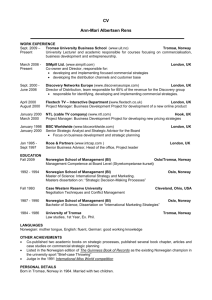

advertisement