I N T E R N A T I O... U N D E R S T R A... The North-South Policies of Canada,

advertisement

INTERNATIONALISM

UNDER STRAIN

The North-South Policies

of Canada,

the Netherlands, Norway,

and Sweden

EDITED BY CRANFORD PRATT

UNIVERSITY OF TORONTO PRESS

Toronto Buffalo London

4

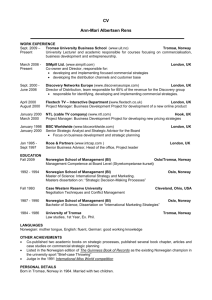

Norway: The Hesitant Reformer

HELGE

HVEEM

In a comparative perspective, Norway appears to have earned a reputation

for being supportive of Third World needs in its foreign economic policy.

Judged by development assistance as a percentage of gross national product ( G N P ) , it is consistently at the head of the ranking of member countries

of the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development ( O I - C D ) .

Norway thus appears to be altruistic. Having supported the demands for

a N e w International Economic Order, in particular the call for an Integrated Programme for Commodities in the United Nations Conference

on Trade and Development ( U N C T A D ) , it also appears to be reformist.

Neither of these characterizations is entirely correct, even if N o r w a y ' s

actual position and policies are viewed in comparative international perspective. This paper examines both the validity and the inadequacy of

this popularly accepted image of Norway. Official policy also includes

a tendency that could be termed conformist. It is partly a consequence

of political and other pressures from fellow O K C D countries, N o r w a y ' s

closest allies in the international political and economic systems, to have

Norway conform to the line adopted by the O K C D collectively. It is partly

a product of perceptions in Norway itself that it ought to follow the U E C D

line in its own self-interest, a self-interest often nurtured by specific and

concrete economic interests. When such economic interests take a rather

shortsighted view or are motivated simply by profit or other interests

specific to domestic Norwegian actors, yet another strand appears in

Norwegian policy - economic self-interest.

The politics of international development is an interplay of these four

tendencies: altruism, reformism, conformism, and self-interest. Their respective strengths on any issue are a function of the resources which the

different groups are able to mobilize for this specific issue. These resources include the support they are able to draw both domestically and

105

Norway

from abroad. The development policy arena is thus to a large extent a

negotiating organization in which a system of tight or loose alliances

operates. However, there is not always a single bargaining process in

which all the tendencies mentioned are necessarily represented, or in

which everybody with a legitimate claim to participate is automatically

present. On the contrary, bargaining is sometimes replaced by hierarchical

and compartmentalized decision-making. Access to the arena is a function

of the power which a specific group can mobilize. Policy-making on

development is thus fragmented, not integrated.

The most important cause of this fragmentation lies in the character

of the development policy-making system which differs from those systems that have developed around well-established public policy sectors

or around specific branches of industrial or economic policy. The policies

of the industrialized developed West can be broadly analysed in terms

of either numeric pluralism (parliamentary representative democracy) or

corporatist policy-making. The latter appears to have grown considerably

in importance over recent decades, and there is wide support for the

proposition that this is certainly true of Norway. Sectors in which corporatism is particularly strong include agriculture, fisheries, and the iron

and steel industries.

Tendencies toward corporatist policy-making have evolved in tandem

with the process of sectoral segmentation. Several important economic

and public policy sectors have developed into segments in which members, problem definitions, values, and standard policy outcomes are well

defined and agreed upon among participants. A segment may also be

defined according to its rules and its routines of problem-solving and

conflict resolution. A segment, finally, cuts across institutions and organizations to which its participants belong. Segment participants often

come to agree more among themselves on how to view problems than

they agree on these issues with members of the institutions to which they

belong or with people who are not members of any segment. The development policy area does not constitute such a segment; rather it appears

to be constantly invaded by other segments. This situation, probably more

than any other, accounts tor the fragmentation of policy-making in regard

to Third World development issues.

As a small and open economy, Norway is naturally strongly influenced

by market fluctuations, by changes in the organization and structure of

world industries, and by the policies and actions of other countries and

of transnational corporations. Aggregate economic calculations that some

three-quarters of the Norwegian GNP is to some extent shielded from the

1

2

1o6

Helge Hveem

3

impact of the international environment appear to underestimate the

impact, including indirect effects, of that environment. International and

domestic processes are thus to be seen as mutually interdependent, not

separate, in the case of Norway.

As a result of the prevalence of corporatist decision-making, the fragmentation of the arena, and the impact of an open economy (here is

almost by necessity a certain diversity, even inconsistency, in N o r w a y ' s

policy on development and Third World issues. There is not one, but

several policies. Nevertheless Norwegian political culture is, relatively

speaking, based on consensus politics. Thus bargaining in a fragmented

decision-making situation promotes positive-sum games, for care is taken

to ensure that divisions do not become too conflictual. The cake is made

bigger so that all the tendencies that demand a bite are able to have one.

Another possible result of such fragmentation is that decision-making in

sub-arenas may become the monopoly of certain interest groups. The

relative strength of the various tendencies and the different fractions is

not, however, constant. It is my belief that the tendencies which I have

named conformist and self-interested have gained strength during recent

years at the expense of the reformist and altruist tendencies. The reformist

mood of the 1970s has ebbed, probably reflecting an international trend

which stems from the perception of economic crisis and the protectionist

mood in the developed industrialized countries. However, factors particular to Norway have also played an important role in changing the political

profile of the country on Third World policy issues.

T H E N E W I N T E R N A T I O N A L DIVISION O F LABOUR

A quick look at N o r w a y ' s economic history in the 1970s and early 1980s

presents a country that has fared well by international standards throughout a decade that many have described as one of general crisis. That

picture could be doubly erroneous. The view that the economic crisis is

a general one has been overemphasized, and the image of Norway as one

of a lucky few is somewhat misleading.

The international crisis is first of all a crisis of institutions and of

policies. This is a period of great instability, most dramatically illustrated

by the immense problems confronting those who attempt to bring even

minimum order to the world's financial and monetary affairs. Moreover,

it is a period of industrial restructuring with the consequent effect, inter

alia, that the already highly inegalitarian distribution of wealth among

107

Norway

and within nations is exacerbated. Only for a few Third World countries

has this change led to rapid industrialization and a narrowing of the gap

between their economies and those of the developed countries. These are

the newly industrializing countries (NICS). Finally, this is a period of

considerable threat to complex social systems, a threat that arises not

least from the danger of nuclear holocaust and serious ecological pressures.

In the long view, the stagflation of the 1970s appears to have arisen

largely from the breakdown of the Bretton Woods regime, from inflationary pressures stemming from the economic policies of the United

States government, and from higher oil prices and the political reactions

(sometimes overreactions)' to those price increases. As isolated factors,

it was the second 'oil shock' that had a serious economic effect on the

world; the first 'shock' was more psychological than economic in its

impact.

Along with these trends there have been some remarkable changes in

the industrial relations among and across nations. An international restructuring race is in progress: all the industrialized countries and several

newly industrializing ones are attempting to secure and consolidate positions in the growth branches of the manufacturing and service sectors.

In the process, the goal - or the effect - is that the stagnating branches

are wound down as much and as quickly as possible. The chief actors in

the transformation are financial and industrial capital, generally aided by

government and blocked, to varying degrees, by labour or other types of

interests. There does not appear to be any general lack of investment in

new and promising activities, such as computerization, biotechnology,

and luxury consumer goods. But there has been a lack of resources for

investment in efforts to maintain full or close to full employment during

the transition.

4

5

Whether or not such resources have been available is a function of

government policy, of the strength of the labour movement, of the resilience of a nation's capital-labour consensus and co-operation, and of

such factors as organizational skills, know-how, and the strength and

variety of the productive structure. In many concrete cases, economic

resources strictly speaking have not been nationally available even though

the political will has been there. This has led to serious strains on political

institutions and has threatened reformist policies in particular. However,

the most important reason for rising social conflict within countries would

appear to be the lack of political consensus on the maintenance of employment, particularly in parties in government. At the international level.

108 Helge

Hveem

the explanation most frequently offered is the lack of co-ordination arising

from a widening gap between national economic policies. Schumpeterian

explanations have, in my opinion, a lesser role.

This is not the proper place for a comprehensive analysis of the implications of these macro-political patterns for the future of the international system. Sutlice it to say that the present high degree of competition.

which is in part a result of challenges to United States hegemony, could

very well lead to a partial breakdown in the capacity of the international

system to regulate itself. In this particular context, competitive restructuring is combined with gross imbalances in the national economic and

financial postures of countries; internationalization coexists with strong

protectionist pressures. Regulatory tendencies do exist. Negotiated trade

agreements, mostly bilateral, and a variety of short- or medium-term

contractual arrangements proliferate; they include countertrade, offset,

orderly marketing, and voluntary export restraint agreements. The transnational corporations continue to organize their activities worldwide in

ways and to a degree that make them dominant players in a number of

branches of the world economy. The state plays a role, not primarily

through multilateral institutions, but by affecting the international competitiveness of national industries. The organization of competitive national capabilities and of selective alliances on the international level

takes precedence over multilateral negotiation and co-ordination. This

appears to be particularly true of the economic great powers in such

important sectors as steel, automobiles, and electronics.

6

7

8

9

This pattern of change has some obvious and some less obvious implications for Norway. As a late industrializer in the Gerschenkronian

sense, and endowed with some particular natural advantages especially

hydro-electric power, the logical choice of national entrepreneurs, foreign

investors, and the state's leaders was to establish and develop processing

industries. Along with shipping and the fishing industry, the paper, metallurgical, and chemical industries became the backbone of Norway's

economic development. The strategy, particularly after World War II,

was export-led industrialization. Shipping has not been integrated with

the industrialization process to any great extent. Although this sector

nominally contributes substantially to the national economy, more than

90 per cent of its business in recent decades has related to trade between

other countries and much of its income has been reinvested abroad in

new ships and, more recently, in internationalizing the sector overall.

In Norway, as in most other industrialized countries, there has also

been a steady transfer of labour from the primary to the secondary and

109

Norway

tertiary sectors. At the same time, there has been a comparatively strong

emphasis on the interests of peripheral regions of the country, in part

because they house the fishing population and many of the processing

industries. 'Tertiarization' and urbanization of society have been tempered

by a relatively strong decentralization policy. This has meant a considerable lianslci of income between regions as well as between economic

sectors. Egalitarianism and welfare state policies have been combined

with policies of full employment and export-oriented growth.

During the 1 9 7 0 s . Norway became a petroleum-producing country in

the course of a very few years. The manufacturing industry stagnated

and even receded during the late 1 9 7 0 s , both in terms of its share of G N P

and in terms of employment. Huge foreign loans in anticipation of

oil income buffered the society against the effects of these dramatic

changes. From the end of the 1970s until 1 9 8 6 , net oil income has been

so substantial that it has been possible to finance the employment,

mostly in the public tertiary sector, of those who were laid off in the

process of recession and restructuring as well as new entrants in the

labour force.

Petrodollars thus saved an economy hit by a recession-plagued industrial sector and a stagnating shipping sector. The story is not, however,

that simple. In international comparative terms, Norway appears to be in

good shape with its comparatively low unemployment rate and a surplus

on the current account balance until the fall in oil prices early in 1 9 8 6 .

There are, however, structural weaknesses. Even if Kaldor's law no

longer applies, manufacturing is still a strategic sector in any developed

economy. And N o r w a y ' s role as a processor has left it with a comparatively large share of its industry in low-growth, low-profitability branches.

Two-thirds of total manufactured exports are derived from these branches.

In 1981 only 7 per cent of exports of manufactures were technologyintensive products compared to an average of 12 per cent for the newly

industrializing countries. Some recent examples, including the success

of Norsk Data, indicate that this situation may be changing, but Norway

is bound to face certain handicaps for years to come.

Norwegian industries are also late comers in another sense: they are

late internationalizers. In a small and open economy, internationalization

- the process whereby national firms establish and/or control production,

marketing, and/or financial or other services in a foreign country - is a

two-way affair. Traditionally. Norwegians have been reluctant internationalizers as far as their domestic economy was concerned; foreign firms

have not been encouraged to establish themselves in Norway. This may

10

110

Helge Hveem

be because Norway is also a Mate comer nation,' at least among the

industrialized countries. It won its political independence only in 1 9 0 5 .

During the decades that followed it was preoccupied with consolidating

its newly won autonomy and passed strict concession laws to regulate

the activities of foreign firms in the Norwegian infrastructure and industry.

Economic 'nationalism' was eased after World War II when Norway

received Marshall Plan aid and access to foreign markets in exchange for

deregulation of its foreign economic relations. The principle of reciprocity

was not, however, generally applied; foreign banks and insurance companies were not allowed to enter Norway even though Norwegian banks

and insurance companies started to operate affiliates abroad several decades ago. This has only begun to change recently.

The return from Norwegian affiliates abroad was only one-quarter of

the value of all exports in 1981. Norway has been a traditional exporter

in contrast to Sweden and some other small industrialized countries. But

outward internationalization has grown more rapidly than exports over

the last few years. Shipowners in particular and bankers have become

eager internationalizers. Whereas only a few years ago practically no

ships were registered abroad, in part because Norwegian shipowners were

critical of the increased use of convenience flag countries, by 1986 onethird of the Norwegian-owned fleet, or some 300 ships, was under a

convenience flag or otherwise registered abroad. Similarly, the capital

of Norwegian banks has grown much faster abroad than at home, with

some 25 per cent of total assets at present in foreign affiliates.

Another new element in the Norwegian foreign economic polity is the

preoccupation with economic competitiveness in a narrow sense. One

consequence of the industrial recession has been a relative deterioration

in productivity. Moreover, N o r w a y ' s anti-inflation policies were put in

place later than those in the countries with which it competes. During

the 1 9 8 0 s , N o r w a y ' s inflation rate has been above the O E C D average.

However, competitiveness in the narrow economic sense is not the only

problem and perhaps even not the main one. The transition to an 'oil

economy' during the 1970s had an inflationary effect. Moreover Norw a y ' s position in the international division of labour made it particularly

vulnerable to recession internationally and to stiff competition from the

NICS. About half of the loss of foreign markets in manufactures during

the last ten years has occurred in the shipyard and the paper and pulp

s e c t o r s . N o r w a y ' s relatively weak export marketing programme is also

a factor of some importance.

N o r w a y ' s exports to and direct investment in the Third World are

11

12

13

14

15

16

111

Norway

characterized by relatively low processing levels. Imports from the Third

World are primarily raw materials. As Norway has become increasingly

self-sufficient in oil, its overall imports from the Third World have decreased; if oil is excluded, they have stagnated. Exports to the Third

World have increased in recent years mainly because of the sale of ships.

This has led to an imbalance in Norway's favour in trade relations with

the Third W o r l d . Direct investment has been concentrated in the OECD

countries. On average, only about 30 per cent of new direct investment

abroad went to the Third World during the period from 1 9 7 9 to 1 9 8 3 .

Moreover, some four-fifths of this investment was in shipping, mostly

in convenience Hag countries.

17

The implications of the changing position of Norway in the international

division of labour appear to be the following:

1 As a 'late comer adjuster," Norway trails most of its competitors in

international markets, with the notable exception of the shipping sector

where Norwegian firms have made a very rapid adjustment to protect

market shares.

2 The processing bias of Norway's industry makes low-cost countries,

in particular the N I C S , its most likely competitors in some of the most

'problematic' sectors of the global economy.

3 To maintain its competitiveness, Norway has to readjust its industrial

structure towards high-technology production. This has led to pressure

to soften or change its social welfare policies and a need to make major

regional resource transfers to avoid having to require greater geographic

mobility of its working force. Up to 1986 oil income made it possible

to reduce these pressures and new technologies may provide similar

assistance. However, the pressures are real and will continue.

4 The need for rapid adjustment puts increased pressure on the sociopolitical cohesion of Norwegian society and weakens the ability of

corporatist national organizations to take decisions that are fully endorsed by labour and employer alike. Thus, there may, in future, be

more conflict within the Norwegian polity over broad economic and

industrial policies. The dramatic fall in oil prices during the first part

of 1986 and the consequent considerable income loss to the state have

made such friction more likely.

5 The pressures for structural readjustment and the fall in oil income will

put increasing strain on the political consensus and make it even more

difficult to combine welfare policies at home with pro-Third World

trade and aid policies.

112

Hclgc Hvccm

T H E

THIRD

W O R L D

POLICY

S Y S T L M

The reformist trend of the 1970s arose from the gradual spread of tiersmondist world-views combined with traditional radicalism and the widespread perception of a new balance of power between the First and the

Third Worlds. Those who united around ihe call lor a New International

Economic Order ( N I E O ) thus formed a rather heterogeneous alliance. B y

linking the reformist alliance to the two polarities set out in my introduction - reformism-conformism and altruism-self-interest - it is possible

to draw a picture of all the major Norwegian positions and schools of

thought on the Third World. The most visible schools, on the whole,

combine elements of the thought or values of more than one of these four

positions. For example, the missionaries, who in some respects were the

first Third World-ists in the Norwegian polity, combine altruism with

values which are close to those of the conformist tendency. They conform

to certain basic Christian values in Western culture and act as transmitters

of those values, but at the same time they act as altruists in socio-economic

settings and thus are not really conformists in an economic sense. It

should be noted that the people who live in the Norwegian periphery and

belong to the lower wage and income groups also are those who most

readily support activities in the Third World by private contributions.

18

The Christian lobby has a background in long-time and relatively extensive missionary activity in areas which are now part of the Third World.

The lobby includes several nationwide missionary associations, but it also

operates through organizations linked to the state church. Den Norske

K i r k e , notably Church Emergency Aid (Kirkens Nødhjelp) and a consultative institution, the Inter-Church Council (Mellomkirkelig Råd), the

channel for Norwegian representation in the influential World Council of

Churches whose current secretary-general is a Norwegian. The Christian

lobby has become more heterogeneous over the past few decades. The

traditional emphasis on missionary goals is still present, but is now combined with newer emphases on development aid and even on trade reform

including some quite radical changes.

Another and perhaps cleuner example of this combination of values

from the two polarities is what has been called social democralic Third

World-ism.

Internationally, its most celebrated expression is the report

of the Brandt Commission. Its basic assumption is that it is in the selfinterest of rich societies to transfer resources to the poorer countries to

help them grow and become wealthier. In this way the North-South gap

will be narrowed and a mounting tension that could eventually lead to

19

113

Norway

open conflict will be reduced. It will also create greater demand for goods

and services from the First World. Social democratic Third World-ism

thus combines reformism and self-interest.

The reformist-altruist tendency is found in youth organizations and in

groups associated with radical postures on Third World policy. They

range from anti imperialists to ecologists of the fundamental or 'deep'

school of thought which holds that the achievement of conservation and

other ecological goals requires radical changes in the social and economic

structure rather than merely superficial measures for the preservation of

nature. These groups sometimes act in common, usually on a single issue

or for a single event, but on occasion they have organized in a more

permanent way such as when the Idea Group on the N I E O was f o r m e d .

20

Finally, there are the economic interests associated with capital and

labour, which most often organize around a particular economic segment.

In some cases, capital and labour, employers and employees, stand together on an issue. When that happens, a formidable alliance is at work

in the political system. As a separate entity, the business community,

even when only the manufacturing industry is considered, is by no means

homogeneous and fully united on the question of Third World policy.

Some fractions of it supported the idea that a new international division

of labour should mean a gradual transfer of industrial production to developing countries. Some made the distinction clearer by saying that the

new division ought to be between technology-intensive production in the

North and labour-intensive production in the South. But the national

industry organizations have had to accommodate differing interests, especially those of the processing industries which are quite labour-intensive. Even relatively small sectors, such as the textile and clothing industries,

are able to influence overall policy if they are well organized.

As far as the political parties and public administration are concerned,

there may be particular interests and there most certainly are different

policies within their ranks. In the democratic-pluralist model of the polity,

parties act as channels of representation and perform the function of

aggregating interests. The public administration, according to this same

v i e w , acts at arms length from lobbies and executes the policy decided

upon in the democratic-pluralist process. The truer image of the Norwegian polity is, however, the corporatist model presented above. Even

that model falls short when an attempt is made to explain the processes

behind Norwegian Third World policies. The corporatist system organizes

the various interested parties into a single decision-making system which

governs the bargaining in the issue-area concerned. The outcome of this

114

Helge Hveem

negotiation is binding on all parties. There are many illustrations of

corporatist decision-making in Norway - in the agricultural, fisheries,

and manufacturing sectors, for example, and in some service branches.

But there is no comparable 'development sector'; there are no corporatist

structures relating to Third World economic policies in which interested

parties negotiate from a common background, delining problems similarly

and sharing the same evaluations and performance criteria. While almost

everybody agrees on what is needed in agricultural production, for e x ample, there is no agreement on why societies are underdeveloped or on

what development is, or ought to be.

21

On the whole, however, the Norwegian political system is characterized

by strong pressure for consensus. This is expressed in the various sectors

and issue-areas, in organizations, and in several general-purpose umbrella

institutions. The latter perform the aggregation function as do national

political institutions, the Church, and the unitary educational system.

Culturally, Norway has traditionally been a rather divided and in some

periods conflictual society. Cultural differentiation is, however, becoming

less and less obvious under the impact of secularization and materialism.

Still, the political culture contains elements of pre- and post-materialism

as well as simple materialist values. Nor is there one cosmopolitan outlook, but several 'internationalist' currents.

22

The 1 9 7 2 referendum on Norwegian entry into the European C o m munity ( E C ) revealed how conflictual the polity is when cultural differentiation and socio-economic contradictions are put to a serious test.

Nevertheless, to portray the referendum process as a battle between internationalist (pro-entry) and nationalist values is a gross misrepresentation of political cleavages. Nationalist sentiment does of course play a

role in these divisions and so it did in 1 9 7 2 . But among the internationalists there were very different currents: on the one hand, 'Third Worldists' admonishing the EC for its imperialism and, on the other, private

business interests anxious to internationalize their activities in order to

increase their profits.

I have identified two sets of structural factors that act to co-ordinate

policy: corporatism and alliance formation. In addition, the strong urge

for consensus has been pointed out. I have also identified the processes

and structures of differentiation and fragmentation. The latter processes

are particularly visible in the area of Third World policy because neither

a corporatist structure nor a corporatist ethos is present. Their absence

can be explained in some degree by the issue's relative newness, but is

also due to the lack of a Third World constituency within the Norwegian

115

Norway

political system - no work force that will go on strike for the Third World

nor any capitalist fractions that will exert strong pressure on its behalf.

There has thus been no compelling need to arrange for the bargaining

that would generate corporatist processes or for a single decision-making

system.

The pressure for consensus and the unitary tendencies within the Norwegian polity interact with fragmented bargaining in ways which largely

fall outside normal mediating procedures. With fragmentation every major

interest group is involved in the processes that relate to matters of direct

concern to them, but neither they nor anyone else is required to ensure

thai the various decisions produced by the separate processes are integrated harmoniously into a coherent policy towards the Third World. These

interests bargain with their respective counterparts in political institutions

and public administration. They all attempt to influence the various segments of policies that touch Third World interests closely: export promotion, industry subsidies, the development assistance budget, and other

public support mechanisms such as research and development budgets.

21

116

Helge Hveem

tax relief, and supportive or protective measures of various kinds. To

avoid too much noise in the system overall, the various interests and their

political administrative counterparts in each segment of policy-making

tend to be given a fair measure of autonomy - at some cost to the overall

unity of N o r w a y ' s Third World policies.

Figures 1 to 3 depict the distribution of the major interest groups within

the two-dimensional mapping of positions introduced above. The hardline realists are composed of business interests and labour groups; they

work with the industry and trade committees in the Storting (parliament)

and the relevant ministries. Among the political parties the Conservatives

(Høyre) come closest to this category. The enlightened realists are represented in the Norwegian Labour party (Arbeiderpartiet) and in the political centre-left, but they also draw support from public servants and

from employers and employees in the more capital- and technologyintensive sectors of the industrial community. This group includes many

aid administrators. After the establishment of a separate ministry for

117

Norway

development aid in 1 9 8 3 , it seemed easier to organize this fragment than

before. However, that was not everyone's perception. The Labour party

wanted development administration to remain under the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and opposed the establishment of a separate ministry, apparently because it feared a fragmentation of N o r w a y ' s overall Third

World policy.

The evolutionaries comprise church organizations and voluntary organizations such as the Red Cross. They command quite strong sympathies among the general public, partly because of their 'non-political'

character, but they are dominant within no particular part of the public

administration. The special role of the Christian People's party (Kristelig

Folkeparti) in the governing coalition may help to explain the ascendancy

of this group or fragment as a channel for development aid. But these

private organizations also benefit from a general belief that they are more

efficient than public assistance, a belief which has been strengthened by

the strong trend towards privatization that has characterized Norway dur-

118

Hclgc Hvccm

ing the last few years. This trend also partly explains the increase in

private sector claims on the development budget. Between 1 9 8 0 and 1 9 8 5

the share of the total aid budget going to private aid organizations quintupled.

The radicals command much attention but have practically no impact

on policy. Their more or less clearly expressed Third World-ism has some

influence on public attitudes and provides a reference point lot other

groups which tend to oppose it. Naturally, their antagonists are most often

the hard-line realists. During the m i d - 1 9 7 0 s , the influence of the radicals

was at its peak and even had some effect on official decision-making.

With the coming of the international economic crisis, however, their

influence over public opinion has receded, to a large extent to the benefit

of the hard-liners.

The shifts in the comparative strengths of these various currents of

thought are largely explained by external economic pressures and the

demands for adjustment that they create. At the moment, conforming

means adapting to the policies of the countries with which Norwegian

business competes in international markets and which Norway trails behind in important respects.

I have suggested that the corporatist model is the more realistic portrayal

of the Norwegian polity, but that it is less representative when applied

to Third World policy. Let me now describe the evolution of N o r w a y ' s

Third World policies against this background.

A G E N E R A T I O N OK E V O L U T I O N A R Y C H A N G E

For many decades, Norwegian missionaries and seamen opened up contacts with what are now Third World countries. The effect of these

contacts on later policy formation was indirect and is difficult to assess.

At most it may have created a paternalistic attitude, at least in those

Norwegian communities where missionaries and seamen were recruited

(and in many parts of the country they were in fact the same communities).

The formal process of development policy formation dates back to the

establishment of the India Fund and the first assistance project, a hospital

in South Korea, in the early 1 9 5 0 s . The considerations which prompted

this decision were chiefly related to security policy rather than to a preoccupation with the social and economic situation in distant parts of the

world. Norway began to formulate policies on Third World issues because

others wanted it to, not for reasons of its own, and, even then, the reasons

related to the escalation of the Cold War and not to the problems of the

24

119

Norway

South. Norwegian policy was a response to an agenda which others set

and which international events shaped.

The first steps were motivated partly by vague perceptions of conflicts

to come because of the poverty of the southern parts of the globe, and

partly by Norway's decision to abandon its traditional neutrality and take

sides in the Cold War by entering the Western military alliance. Conflict

avoidance was still very much the dominant mood in the country, however, if not always a practical choice. With the Korean War, decolonization, and the emergence of non-alignment, Norway reluctantly developed

a policy on Third World issues, less because it wanted to than because

it had to.

25

A desire for conflict avoidance naturally resulted in compromises.

During the 1950s and even later, Norway had sought to combine the

pursuit of certain ideals - a strong United Nations and the protection of

the interests of small states - with an avoidance of conflict with its closest

friends and allies. These objectives were not easily combined. In this

period, for example, Norway struggled uneasily with the need to choose

between supporting decolonization and backing those allies, such as France

in Algeria, which sought to maintain colonial rule. In many cases where

Norway had to take a position, if only as a member of the United Nations,

it chose, to use Hirschman's words, loyalty, not voice - if exit was not

feasible. '

The first steps towards a truly national policy on the Third World were

taken at the beginning of the 1960s. During the 1 9 5 0 s , Norway had run

two assistance projects, one in Kerala, India, and another in Seoul, South

Korea. These two projects were clear-cut expressions of the predominance

of security considerations rather than development assistance in policymaking. Development assistance was one of the easier w a y s , politically,

for the government to pursue security considerations, for it helped it to

satisfy groups opposed to membership in the North Atlantic Treaty Organization and the predominance of military policy, particularly those

within the Labour party itself which was in power for practically all the

1 9 4 5 - 6 5 period. These fractions were the forerunners of today's radicals. They were idealists with a distaste for the Realpolitik which governments must address; they were the proponents of the moral imperative.

But their influence on policy remained marginal until international circumstances created a breakthrough for a perspective which the government, supported by other groups (see figure 1 ) , had earlier opposed:

namely, that structural reform was more important than aid.

26

27

120

Helge Hveem

While Norway could move closer to Third World positions on decolonization during the 1960s, mainly because the developing countries

themselves became more moderate on that issue, it opposed their demands

for reforms to international trade. Free trade was the first principle in

N o r w a y ' s foreign economic policy. In principle - and for a long time in

practice

Norway was not willing to make exceptions In that rule in

order to help the developing world. Charges that the international system

was a cause of underdevelopment were squarely rejected. The PrebischSinger-Myrdal critique was not taken seriously, even though a Norwegian

was secretary-general of the United Nations from 1946 until 1 9 5 2 . The

issue was not thought salient enough to warrant a change of policy.

Moreover, the principle that all trading partners must be treated equally

(the most-favoured-nation principle) was the guiding precept, it was said,

for the more open international trading system that was of primary importance to Norwegian decision-makers. Saliency of issues, intensity of

perceived national interests, and the extent of international (and national)

disagreement over issues are the three factors that have determined Norw a y ' s political behaviour on Third World policy.

During the 1960s, there was a gradual shift in perceptions of development problems. The change in view led to the formulation of a set of

principles for development policy at the beginning of the 1 9 7 0 s . The

policy of 1962 was reformulated in 1 9 7 2 . The security motive was now

de-emphasized, quite probably under the impact of détente. The achievement of economic growth, which in 1962 had been assumed to require

massive transfers of capital and technology, was now thought to depend

on structural reform in the developing countries. Economic self-interest

in aid programmes was de-emphasized. Aid should not be tied to Norwegian business interests. Several factors may have caused these shifts.

Among the most important, however, were a certain pressure from the

O E C D ' S Development Assistance Committee ( D A C ) and domestic pressures from youth and Christian organizations, independent intellectuals,

and the media.

When N o r w a y ' s policy towards the New International Economic Order

was formulated in 1 9 7 4 - 5 , most of these principles were retained. What

was new was the recognition, openly rejected in earlier rounds of public

debate, that underdevelopment was caused in large measure by international structures. A report to parliament from the development agency in

1 9 7 4 stated that 'developing countries still find themselves in a position

of economic dependence on the rich part of the world through a system

of ownership control, division of labour and power which effectively

2 8

121

Norway

prevents them from attaining full economic and social independence."

The dependencia thesis had finally made its way into government policy.

The report even stated as an official view that 'the free market mechanism

has not led to equitable results, but has on the contrary served to widen

the disparity between the rich and the poor countries.' When the N I E O

negotiations started in 1 9 7 4 . the Labour parly was in power. Popular

support for the N I E O agenda was strong in Norway, both by historical

and by international standards. There was widespread agreement, which

even included the Norwegian Association of Industries (Norges Industriforbundet), that the N I E O programme ought to be carried through. A

great number of organizations and professions held N I E O meetings. It

was the most frequently discussed issue in the foreign policy debates in

the Storting during 1 9 7 6 and 1 9 7 7 . Then came a change.

24

30

Policy is naturally sometimes of a declaratory nature: principles are

not followed in practice. This is certainly true of elements of N o r w a y ' s

Third World policy. One may even speculate that N o r w a y ' s relative

reformism arose from a rather cynical calculation that since the opposition

of the great powers to N I E O principles guaranteed that they would never

be implemented, there was no risk in supporting them. However, it is

probably truer to liken Norway to Ibsen's Peer Gynt who, having professed a different and more ethical view than that of his fellows, follows

the group 'protesting for the whole world.' But the thesis I have advanced

- that there has been deliberate fragmentation of policy-making on Third

World issues, accomplished through separate channels of decision-making and implementation - is the best explanation. This certainly appears

true for the politics surrounding N I E O issues.

Norway had consistently supported the Integrated Programme for C o m modities ( I P C ) since the U N C T A D secretariat introduced it in 1 9 7 6 . It was

the first of the industrialized countries to pledge a contribution to the

Common Fund which was the central and most important innovation in

the I P C . Norway was active at the 1 9 7 6 U N C T A D conference in Nairobi

in organizing the coalition between the majority of O E C D countries and

the developing countries that launched negotiations on the I P C against

opposition from the major economic powers in the O E C D . However,

Norway did little save support in principle Third World industrialization

and the build-up of independent national research and development capacities as called for in the declaration of the United Nations Conference

on Science and Technology for Development and the Norwegian national

submission to that conference. This clearly reflects the fragmentation

process.

31

122

Helge Hveem

Following the two special sessions of the United Nations in 1 9 7 4 and

1 9 7 5 and the 1 9 7 5 conference of the United Nations Industrial Development Organization ( U N I D O ) , Norwegian authorities issued statements

in support of industrialization targets for the developing countries. However, reports to parliament on both export policy and manufacturing policy

strongly supported almost across-thr board expansion or preservation of

existing Norwegian industries. Moreover, while Norway has supported

international regulation of trade in raw materials, it has been sceptical

about the value of international producer associations except in very

general terms. Norway has also hesitated to support developing countries'

demands for stricter and binding control of transnational corporations and

has only conditionally accepted the right of these countries to nationalize

mining and other industries under foreign control. Until the change of

government in 1 9 8 6 , it never seriously considered seeking closer coordination with the Organization of the Petroleum-Exporting Countries

( O P E C ) , even though its petroleum production was greater than that of

several middle-sized O P E C countries by the mid-1980s and thus could

have had an impact on market developments. In all these instances, then,

policy decisions taken by different structures within the fragmented decision-making process ignored or undermined the broad commitments

made by Norwegian representatives at U N C T A D , U N I D O , and the United

Nations. But conflict avoidance has also led Norway to choose associated

status in the International Energy Authority, the least that was expected

of it as a Western ally, in order to avoid full membership.

32

33

Finally, N o r w a y ' s merchant shipping policy - its most important area

of bargaining vis-å-vis the Third World - has until quite recently been

one of strong opposition to developing countries' demands. Norway worked

actively at liner conferences against the new market-sharing arrangements

sought by the Third World because regulations limiting access of third

country shipping companies would obviously be contrary to its own shipping interests. Then Norway changed its position, moving towards a

compromise and towards setting up affiliates abroad. It even negotiated

an agreement with one developing country whereby one of N o r w a y ' s

shipping companies would carry all that country's share of trade under

the new market-sharing agreement (Leif Høegh's contract with the People's Republic of the Congo).

Norway has been moderately conservative as far as demands for reform

of international institutions are concerned. It has usually gone along with

common O E C D policies on International Monetary Fund and World Bank

matters. This conservatism has also meant that Norway has consistently

123

Norway

supported United Nations institutions against attacks from those seeking

to weaken them. Thus, the United States withdrawal from the International Labour Organization and the United Nations Educational, Scientific

and Cultural Organization has not found much support in Norway.

N o r w a y ' s profile on N I E O issues is multifaceted and has changed over

the past ten years Its most consistent reformist stand is thai on the IPC.

the raw materials issue, perhaps because the international stabilization of

commodity prices would benefit some branches of Norwegian industry

as well. During the years when the I P C was debated, the government

spent several hundred million kroner on a domestic price stabilization

fund for a dying copper industry. Nevertheless if the U N C T A D proposal

had been carried through, the net effect on the Norwegian economy of

an across-the-board price stabilization during the years of depressed world

prices would have been to increase the import bill significantly more than

the revenues from the export of the affected commodities.

In other respects, N I E O policy was as much take as give. With respect

to the strong pressure from developing countries for market access, Norwegian policy was no more liberal than that of other O E C D countries. It

created a new institution, N O R I M P O D , to promote imports from the Third

World, but the agency has been weak and the political and economic

resources behind it are very small compared to the support given to export

promotion. In fact, at the same time as the government voted for the first

N I E O resolutions in the United Nations, it also introduced a battery of

incentives for export industries. The amount of export credit was greatly

increased, as were guarantee schemes for both exports to and direct

investment in developing countries. These measures were introduced even

though many questioned the usefulness of such activities for development.

The government had - as we have seen - legitimized the dependency

critique at the same time as it took these trade and investment initiatives.

Was it not inconsistent to seek to increase the very kind of trade and

investment relationship that had created dependency in the first place?

Or is this another example of either declaratory policy. Peer Gynt tactics,

or fragmentation of policy? I favour the latter hypothesis, but it cannot

be denied (hat there was and still is many a Peer Gynt in N o r w a y ' s Third

World polity.

During 1 9 7 7 - 8 government policy changed dramatically. In the two

preceding years, the public authorities had borrowed large amounts in

the international capital markets into which petrodollars were flooding.

Most of this borrowed liquidity was used to finance increased consumption; relatively little was invested. Revenues from oil were just starting,

124

Hclgc Hvccm

and there was no danger of becoming overly indebted; but, as one would

expect, the inflation rate went up, an increase exacerbated by exceptionally high wage increases. Then, suddenly, the brakes were applied in

1 9 7 7 - 8 : a complete wage freeze was imposed (with the consent of labour)

in an attempt to beat back inflation. At the same time, more and more

people realized thai the oil industry was not going to give the mainland

economy as much of a stimulus as was first expected. Mainland industry

continued to lose markets abroad. It was time for Norwegian industry to

concentrate on its competitiveness and to strive to reconquer its markets.

This 'go-stop-go' policy reinforced a basically self-interested mood that

was contrary to international reformism. The business community was

also able to point to what was happening in other O E C D economies and

in the N I C S - increasing protectionism, monetarism or supply side economics in some important places, and less emphasis on full employment

policies. The pressure for Norway to conform with these trends was high.

Increased attention was also directed to those economies that were both

N o r w a y ' s competitors and biggest markets. The self-interest-conformist

tendency was clearly in the ascendant. How did this affect relations with

the Third World?

T H E F R A G M E N T E D S Y S T E M AT WORK

The renewed emphasis on export promotion was accompanied by growing

internationalization, although the drive for internationalization has only

become particularly strong in the past few years. Before that, there was

a major export drive directed towards the Third World in an attempt to

sell ships constructed in Norwegian shipyards which had suffered during

the 1 9 7 0 s from the combined effect of reduced global demand for new

ships and stiff competition from the so-called low-cost producers, especially Japan and South Korea. After reviewing an aborted attempt to

create a restructuring fund for industry, I shall assess this campaign. Then

I will look at the Norwegian policy on the Multi-fibre Arrangement ( M F A )

and offer a short review of the relationship between business and development. Finally, I will examine the new relationship between the Norwegian shipping lines and the Third World.

The

First

NIEO Failure:

A

Fund for Industrial Restructuring

In response to the Second General Conference of U N I D O in Lima in 1 9 7 5 ,

the Norwegian government pledged to work for a transfer of manufacturing to developing countries. A working group was set up in the Ministry

125

Norway

of Foreign Affairs, thus giving the impression of a serious will in government to take practical steps to fulfil the U N I D O goal. Prime Minister

Nordli set out this intention quite strongly in a speech in November 1 9 7 6 .

The working group in turn stressed O E C D reports that rejected the widespread notion that increased imports from the Third World would result

in a direct loss ol jobs in ihe industrialized countries; it noted what were

then seen as the concrete results of the Netherlands' restructuring scheme

which had been adopted in 1 9 7 4 . The working group identified three

situations in which public support for restructuring should be provided:

when the import trade from developing countries was liberalized; when

production facilities were moved from Norway to a developing country;

and when there were considerable fluctuations in the market situation

faced by Norwegian manufacturing industries. The new fund, to be administered through the existing Industrial Fund, would have a first-year

budget of 1 0 0 million kroner (about U S $ 5 . 4 7 million).

The fund proposal did not see the light of day. It should have been

made public at the end of January 1 9 7 7 , when a government decision to

launch it was expected. There are several accounts of what happened.

Some suggest that the project was not well enough prepared and/or that

other schemes were preferred by the decision-makers. Perhaps therefore

the project was simply cancelled. Another version is that industrial leaders

believed that the proposed scheme had insufficient financial backing to

warrant their active support. A third account is the most compatible with

the model of corporatist decision-making. It holds that the Federation of

Trade Unions (Landsorganisasjonen) acted directly on the Labour government with which it has close links. The federation demanded that the

project be cancelled because it would mean a loss of jobs in Norway.

The Labour government had been in a precarious position: its electoral

support in the 1 9 7 3 election had been the lowest since the 1 9 3 0 s and it

badly needed labour's support in the 1 9 7 7 election if it was to stay in

power. The negative reaction of the federation was sufficient to put the

project in a drawer in the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. Having investigated

the case carefully, I am convinced that this third version is the soundest.

Lack of active support for (he project from business leaders made it easy

for labour to veto the fund. However, the primary reason for shelving

the proposal was trade union opposition.

The Ship Export Campaign

When the NIEO process was set in motion internationally, the shipping

crisis was already having serious effects on employment in the world's

126

Helge Hveem

shipyards. In Norway the industry consists of a large number of small

and medium-sized yards and a few big ones. The shipyard workers belong

to one of N o r w a y ' s most influential unions, the Metalworkers' A s s o ciation (Jern-og Metallarbeiderforbundet). Many of the yards are located

in small communities along the coast which offer few alternative sources

of employment. The demand for public support of the shipyards was very

strong and the government and the Storting acted quickly to save them.

Special measures of economic support were introduced. Economic

subsidies were given, apparently on the condition that they be used not

only for immediate needs but also to support measures to readjust production to new products and higher productivity. Many looked to the

Third World as a potential market for Norwegian ships. Shipowners had

requested and received a guarantee scheme whereby the state would

prevent second-hand ships from being dumped by Norwegian shipowners

facing bankruptcy. Measures were now taken to support the yards in ways

that broke several of the accepted 'rules of the g a m e ' in Norway.

First, a group of shipyards got a 450-million-kroner contract for delivery of ships to Indonesia in 1 9 7 6 . Associated with this contract was a

further 70 million kroner in direct aid to the country. The contract had

been negotiated by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs in competition with

several other governments (particularly, it appears, the Dutch), with the

Industry and Commerce Ministries organizing the domestic link, including getting the aid funds to secure the contract. The aid component of

the contract was strongly opposed by the aid bureaucracy. It saw the deal

as a purely commercial one and argued that this type of aid was a contradiction of a long-standing Norwegian principle. Moreover, aid to Indonesia was a negation of the concentration principle. A n d , finally, the

continued harshness of Indonesia's rule in East Timor had caused criticism

of Indonesia in the m e d i a . Those who organized the contract, in contrast,

claimed that it was within the rules set by the O E C D . They also said it

would be a one-time occurrence. An official investigation of the use of

the aid money later showed that one-third had been a simple ' g i v e - a w a y , '

while the rest had been used for relatively acceptable purposes such as

training in Indonesia. "

The largest commercial bank in Norway was apparently instrumental

in setting up the initial contacts and the financial package lor the contract

with Indonesia. The successful negotiation of this aid/trade promotion

package led the government to launch a major campaign to obtain similar

contracts. The political and administrative head of the Ministry of Commerce and Shipping was the lead actor. Its trump card was a scheme that

34

127

Norway

used development assistance funds to offer interest subsidies, nominally

a grant element up to 25 per cent of the contract amount, but in reality

even more than that. Several billion kroner in credits and guarantees

were allocated between 1977 and 1 9 8 0 . At first, the aid agency, the

Direktoratet for utriklingshjelp ( N O R A D ) , was required formally to evaluate and approve the contracts. Later, most ship sales assisted in this

way were exempted from N O R A D evaluation. Attempts to allocate aid

money to cover future defaults on repayments of the credit led to conflicts

that were settled by a compromise. As defaults at present amount to

several hundred million kroner a year, there is still much controversy

about whether they should be covered by the aid budget or that of the

Ministry of Commerce. This conflict reflects a clear and open split between the altruistic and the realist tendencies in the Norwegian polity, a

split that has divided the post-1977 governing coalition.

36

37

The shipyards maintained employment, but these special arrangements

postponed rather than facilitated a restructuring of the shipbuilding industry. The political-administrative leadership felt that they had probably

broken normal rules of risk-avoidance, offended desirable procedures for

the proper administrative handling of contracts, and at best had worked

at the margins of what O E C D rules allowed. According to a junior member

of government at the time, Norwegian negotiators went out of their way

to secure contracts with developing countries, even though many were

uneasy about the negotiating practice and fearful of the risks associated

with the outcome. The strong influence of the industry and its corporatist

structure of bargaining prevented these doubts from surfacing, however.

For the realist, practically any export contract with a Third World

country is a sort of development assistance. For the altruist, there is no

such easy equation; the question must be carefully considered according

to the criteria set down for Norwegian development aid, notably the

targeting of aid to the poorest groups of the population and to the least

developed countries. The conflict over which budget should cover the

risk of default on export credit contracts therefore gave a rather representative picture of the contradictions within the Norwegian Third World

policy system.

38

39

The

Multi-fibre Arrangement:

Norway

as Free

Rider

40

There has always been a relatively strong coalition of political, administrative, and business leaders in Norway that favours multilateral solutions over unilateral action or bilateral deals. The rationale has been

128

Helge Hveem

simple: as a small and open economy, Norway is best served in the long

run by resisting the temptation to be a free rider. To adopt such a role

would mean that Norwegian interests benefited from international arrangements worked out and sponsored by others without having to share

in defending the arrangements or carrying a part of the costs. Such games,

according to the official view, are bound to be won by larger countries

with greater resources; small countries must seek a game regulated by

binding rules. Nonetheless, N o r w a y ' s policies over the past ten years

give some clear illustrations that the temptation to be a free rider has

been irresistible. Policy on the Multi-fibre Arrangement, the agreement

on trade in textiles and clothing, is particularly illustrative.

The Norwegian textile industry has been one of the branches of the

economy most affected by imports following the opening up of the economy. Its share of the domestic textile and clothing market has fallen from

some 70 per cent in 1 9 6 0 to less than 30 per cent in 1 9 8 0 . The industry

is still relatively labour-intensive, it employs a large number of women,

and it is to a large extent located in regions of the country which are on

the periphery and always threatened by unemployment. The proponents

of national protection for the industry have pointed to all these factors

and have also argued that national military preparedness requires a substantial local textile industry.

While the Norwegian industry has lost significant market shares in

Norway, this loss has arisen from the free-trade arrangements under the

European Community and the European Free Trade Agreement. Markets

have not been lost primarily to Third World producers. To maintain the

industry at its present level of employment, the government and the

Storting have appropriated funds to subsidize the industry's wage bill.

These measures have not been considered sufficient by the industry's

lobby which has demanded and obtained sufficiently broad protectionist

measures that Norway was unable to sign the first M F A in 1 9 7 3 . Industrial

policy thus overruled foreign policy.

In 1 9 7 6 , a local unit of the textile workers' union ran an advertisement

in the press stating that it opposed N o r w a y ' s implementing the N I E O .

Since then employers and employees in the textile and clothing sectors

have formed a united front which has commanded the almost unwavering

support of the Ministry of Industry, especially under the Labour government. The sector, in other words, appears to provide a perfect example

of corporatism in action. It managed to keep Norway outside the M F A ;

Norway was the only industrialized country not to join. It alone introduced

bilateral and unilateral quotas to cope with 'problematic export countries'

129

Norway

alongside and in addition to the global quotas that were allowed by the

rules of the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade ( G A T T ) . Six southeast Asian countries were allocated special quotas. Hong Kong at that

time ( 1 9 7 7 ) had some 55 per cent of all 'low-price exports' of textile

products to Norway and had increased its volume of exports to Norway

by 40 percent annually from 1 9 7 3 lo 1 9 7 b . N o r w a y ' s demand that Hong

Kong reduce its exports by 40 per cent was promptly rejected, and Hong

Kong brought the case before the G A T T council.

Earlier, Norway had been instrumental in having G A T T accept the right

of small importing countries to protect 'minimum viable production' in

a domestic industry (the so-called Nordic clause). Nevertheless, and despite considerable pressure from other Nordic countries and from the

United States, Norway also resisted appeals to join the second M F A . This

was a source of some embarrassment, particularly for the Ministry of

Foreign Affairs, because it contrasted starkly with the p r o - N I E O profile

that ministry representatives were attempting to promote.

The domestic bargaining over the M F A and Hong Kong issues attracted

a good deal of public attention. Formally, it was up to the Ministry of

Commerce and Shipping to decide policy on these issues, and the ministry

appears to have been firmly behind the industry's refusal to join the M F A

II until about 1980. At that time, the chairman of the Labour party was

appointed minister of commerce and shipping. That party's leaders had

been influenced to a considerable extent by the Brandt Commission both directly and indirectly through the Socialist International which had

been penetrated by its ideology. Under the new minister, the ministry

amended its active protectionist stance and attempted to mediate between

the reformist coalition on the one hand and the industrial hard-line realist

lobby on the other by exploiting the preference for consensus which is a

feature of Norwegian politics. Other factors also favoured a change of

policy. There was the need for Norway to conform to the dominant

international trend while it occupied the chair of the North-South C o m mittee of the O E C D . Moreover, Norway was losing its case in the G A T T .

The ministry, therefore, sought an agreement with Hong Kong and moved

to make Norway a member of MFA II . It failed in both projects.

The textile and clothing lobby (in which the textile and clothing workers

and the manufacturers co-operate closely) is considered one of the most

effective pressure groups in the Storting. It had succeeded in getting the

Industry Committee unanimously to oppose the agreements. It had also

worked so effectively on the Foreign Affairs Committee, normally a firm

supporter of the Foreign Ministry's point of view and often more refor-

13o

Helge Hveem

41

mist-altruist than the rest of the Storting, that the committee supported

the lobby's view. The lobby's influence on politicians is of long standing,

but it was helped by the fact that the decision was taken only months

before a parliamentary election. Moreover, the Labour party supported

the lobby and the Association of Industries did not oppose it. It was left

to fractions of the evolutionaries and the radicals to support the p r o - M F A

v i e w , as the support of enlightened realists dropped away under the

pressure of the lobby and upcoming elections. Another factor was that

the pro-Third World coalition was not firmly convinced that Hong Kong

and the other cheap-labour textile and clothing exporters in Asia were a

particularly good cause to defend. Nor was it a natural ally for the Foreign

Ministry or the textile and clothing importers' organization which also

supported M F A membership. The Foreign Ministry's strongest card was

the advantage to be gained from conformity with the United States and

other O E C D countries, and officials pointed to the hazards of being left

alone and outside 'the club' of industrialized countries to which Norway

otherwise clearly belonged. But the segmentation of corporatist decisionmaking worked against those who supported the M F A . The firmness of

the 'core' coalition - the textile and clothing employer-employee lobby,

the Ministry of Industry, and the Industry Committee in the Storting was invincible. It was even able to force the Ministry of Commerce and

Shipping back into the fold when the latter sought to abandon the position

supported by the corporatist coalition.

Norway finally did join the M F A during 1 9 8 4 - 5 after securing a compromise solution in G A T T negotiations over the Hong Kong complaint.

This does not, however, mean that the lobby has had to give in. Rather,

the M F A had become so protectionist that joining it involved little concession towards more open trading. At the same time, the Norwegian textile

and clothing industry has finally begun adapting to new technology and,

more important, to product innovation, making it more competitive. It

is thus conforming to the international trend: restructuring towards the

higher value-added levels of the product chain and letting low-cost producers take a larger share of the lower level products.

42

Commercialization

of Aid: Altruism

vs Self-Interest

One of the more important battlefronts in the Norwegian Third World

policy system has been the issue of tied aid. Since 1 9 6 7 , the stated

principle in government documents has been that there should be no tying

of aid to Norwegian commercial interests. Both moral and practical eco-

131

Norway

nomic reasons have been given in defence of the principle against the

inevitable attempts of industrial lobbies to gain special advantage through

the tying of Norwegian aid to Norwegian goods and services. The tying

of aid in this way has been opposed by a loose coalition, with ethical

evolutionaries siding with Third World-ists of various kinds to lobby the

Foreign Affairs Committee to maintain the principle set down most firmly

in the 1 9 7 2 report to parliament. The altruist coalition has seen its moral

and political arguments supported by macro-economic arguments such

as those O E C D studies which concluded that tying aid increased real costs

of projects for recipients. A number of public servants, notably in N O R A D ,

have adopted its view and even become outright members of the alliance.

The embryo of a segment - a development-oriented alliance - has emerged.

To widen and consolidate this support, the altruists have not totally opposed a linking of commercial interests with the aid sector. Their openness

to bargaining has led to compromises, but it has also enabled them to

defend some territory for a Third World-ist policy with an emphasis on

targeting poor groups and countries, the satisfaction of basic needs, and

self-help.

43

The p r o - N i E O position of the Norwegian government in 1 9 7 4 - 5 was

accompanied by a battery of incentives meant to induce industry to become involved in the Third World, mainly through investments, joint

ventures, and similar activities. These incentives were largely in conformity with O E C D and World Bank standards and rules. They did not

result in any major increase in Norwegian direct investment, joint ventures, or other forms of activity. The considerable internationalization

effort that did occur, as noted earlier, has been directed towards the other

O E C D countries and a few N I C S , not towards the great majority of L D C S .

Before proceeding, it may be useful to clarify the concept 'commercialization of aid.' It occurs when an actor consciously appropriates public

funds that have been allocated for development aid according to specific

publicly known guidelines in such a way that the specific commercial

interests of that actor take precedence over those guidelines. But where

is the line to be drawn? When is an aid project commercialized (according

to the definition offered here) and when is it development-oriented? Are

there circumstances and conditions under which commercial interests and

development goals can be combined to yield both a development effect

and a profit to some Norwegian commercial interest? The public debate

over these questions in Norway has split into three positions: the altruists

who oppose the tying of aid; the position of many industrialists and labour

spokesmen that all projects with participation by Norwegian industry in

132

Helge Hveem

and by themselves would yield a development effect and that there is no

conflict between the tying of aid and the pursuit of development; and a

middle position which accepts that there is a potential conflict between

development concerns and commercial interests but believes that the

conflict can be resolved by setting detailed conditions for the participation

of private business.

I would suggest that the business position has been gaining ground

despite attempts by some altruists to defend their view by advancing

compromise solutions supporting the middle position. Three recent developments provide evidence of the rising force of economic self-interest

in N o r w a y ' s Third World policy.

The first concerns what may be termed the geopolitical location of

publicly aided business activities in the Third World. At intervals since

1 9 7 2 this issue has provoked controversy. The altruist-reformist coalition

has attempted to encourage the private business community to locate

some of its activities in those countries which are the main recipients of

Norwegian development aid. Most of these are classified as least developed countries. A great number of feasibility and preparatory studies,

wholly or partly financed by N O R A D , have been carried out in these

countries by Norwegian firms, but Norwegian business has rarely decided

to invest in them or to commit itself in other permanent w a y s . There are

three main reasons for this. First, the N I C S are more attractive commercial

prospects because of their potential as markets - a view Norwegian business shares with the international business community at large. Second,

Norwegian business decision-makers are on the whole risk avoiders - in

contrast to the average international business leader who is relatively

more of a risk taker. The poorer L D C S often exhibit weak infrastructures,