INTRODUCTION The S c a n d i n a...

advertisement

INTRODUCTION

The Scandinavian and the s o - c a l l e d "like-minded" c o u n t r i e s in

g e n e r a l , h a v e earned a reputation for being among the most

" p r o g r e s s i v e " c o u n t r i e s of the Northern Hemisphere in dealing

with the d e v e l o p i n g s o u t h .

T h i s r e p o r t will take a critical

look at this r e p u t a t i o n , which we believe is only partially

deserved.

T h e r e p u t a t i o n , it would seem, h a s been gotten from a

v a r i e t y of s o c i a l , economic, and political s o u r c e s . The social

fabric of these c o u n t r i e s is, r e l a t i v e l y e g a l i t a r i a n , although

c l a s s contradictions and conflicting g r o u p i n t e r e s t s still e x i s t .

T h e y a r e "mixed economies" with a r e l a t i v e l y wide s u p p o r t for

public intervention in the economy.

In the c o n t e x t of the

NIEO d e b a t e , important political factions draw analogies from

these domestic equalizing and public r e g u l a t o r y p r o c e s s e s to

the international s y s t e m :

What is a c h i e v e d domestically must

be to the l a r g e s t possible e x t e n t a c h i e v e d internationally. One

question is whether t h e r e r e a l l y i s public s u p p o r t for s u c h

international solidarity a n d , if s o , to what e x t e n t .

In their foreign p o l i c i e s , Scandinavian countries follow

different p a t h s due to their r e s p e c t i v e s t r a t e g i c geopolitical

positions in the East-West c o n t e x t .

With r e g a r d to their

policies toward d e v e l o p i n g c o u n t r i e s , the Scandinavian g o v e r n ments jointly h a v e come out r e l a t i v e l y s t r o n g l y in s u p p o r t of

decolonization and the liberation movements in A f r i c a , and in

denouncing

apartheid.

T h e i r development aid

policy is

illustrated by the fact that Sweden and Norway now r a n k on

top of the DAC list of industrialized donor countries in terms

of the p e r c e n t a g e of GNP channeled as official development

a s s i s t a n c e , a position t h e y s h a r e with the N e t h e r l a n d s . A l s o ,

WESTERN EUROPE AND THE NIEO

46

the S w e d i s h - N o r w e g i a n " a x i s " has come to form the b a c k b o n e ,

with the D u t c h , of the like-minded c o u n t r i e s of the n o r t h .

T h i s g r o u p i n g was formed d u r i n g p r e p a r a t i o n s to the 1975 7th

Special Session of the UN General A s s e m b l y . It made its first

major demarche t h r o u g h the initiative taken at UNCTAD IV and

r e s u l t i n g In" TS mostly minor industrialized c o u n t r i e s v o t i n g in

favor of Resolution IV (93) on the I n t e g r a t e d Program for

commodities.

Despite these f a c t s , to which we shall r e t u r n , why is the

" p r o g r e s s i v e " reputation of t h e s e countries partially u n d e s e r v e d or at least e x a g g e r a t e d ?

S c a n d i n a v i a is economically

and c u l t u r a l l y closely i n t e g r a t e d with the Western w o r l d . The

question therefore is whether the economic b a s i s of the

Scandinavian societies is so fundamentally' capitalist and so

much a p a r t of the "international division of labor" established

by the economic p o w e r - h o u s e s of the capitalist N o r t h , that

both capital and the state in these c o u n t r i e s are bound to

follow the logic of the s y s t e m ? In other w o r d s , the economic

s t r u c t u r e p u t s absolute limits on what these c o u n t r i e s can do

with their international e n v i r o n m e n t s .

If s u c h a view is

c o r r e c t , it follows that w h a t e v e r p r o g r e s s i v e image is p o r t r a y e d internationally is mostly due to a political and cultural

system which on the one hand r e f l e c t s a certain ideological

tradition (socialist internationalism) and on the o t h e r r e p r e s e n t s c e r t a i n internal p r e s s u r e g r o u p s and idealistic factions

within public opinion.

An a l t e r n a t i v e h y p o t h e s i s would be that the combination

of economic realism and political idealism, which is what we

e x p e c t to f i n d , is d e l i b e r a t e or i n e v i t a b l e .

It is deliberate in

the sense that the S c a n d i n a v i a n s h a v e chosen the path that

can be d e s c r i b e d as the "Peer G y n t a p p r o a c h . " T h i s a p p r o a c h

is named after the main c h a r a c t e r in the famous Ibsen play

.who, when faced with a dilemma, followed the "realist" choice

of his companions, but made it clear that he "protested to the

whole world" while doing s o , knowing there was an a l t e r n a t i v e

"idealist choice.

It is inevitable that the Scandinavian s t a t e s ,

r e p r e s e n t i n g r e l a t i v e l y small economies, h a v e no choice but to

accommodate themselves to the dominant t r e n d s and actors in

the

international system with which they a r e i n t e g r a t e d .

We s u g g e s t that there are five basic o b s t a c l e s to the

implementation of the NIEO.

T h e first and most basic is the

c o n s i d e r a b l e d i s c r e p a n c y between words and d e e d s .

Second,

this d i s c r e p a n c y a r i s e s from the need to accommodate v a r i o u s

factions of society p u r s u i n g different i n t e r e s t s .

Third,

Scandinavian c o u n t r i e s h a v e to adapt to their international

environments.

T h e r e is some truth in the allegation, often

r e p e a t e d by r e p r e s e n t a t i v e s of both state and b u s i n e s s , that

these c o u n t r i e s cannot a c t i v e l y implement the written principles

of the NIEO as long as o t h e r and more powerful industrialized

c o u n t r i e s do not do the same in multilateral! y a g r e e d upon

1

SCANDINAVIA/LIKE-MINDED COUNTRIES

47

schemes.

We w i s h , h o w e v e r , to e x p l o r e whether this is

n e c e s s a r i l y t r u e under all c o n d i t i o n s .

F o u r t h , another possible obstacle to the implementation of

the NIEO in the context of S c a n d i n a v i a , is the insufficient

information on and a w a r e n e s s of the NIEO i s s u e s among the

public.

Furthermore, t h e r e is still a lack of s t r o n g political

s u p p o r t among the informed public to e n s u r e that practice

follows the e s p o u s e d p r i n c i p l e s .

T h e s e h y p o t h e s e s coincide in

part with the first obstacle that assumes that a d i s c r e p a n c y

a r i s e s from the need to accommodate contradicting i n t e r e s t s ,

although they b r i n g in additional factors as well.

Fifth, the effect of the European economic c r i s i s is to

p o s t p o n e , or work a g a i n s t , the NIEO.

P r e s e n t l y , most people

in the like-minded countries of Europe seem to be concerned

with the economic c r i s i s and with unemployment at home r a t h e r

than with the c r i s i s of the NIEO.

In one v e r s i o n of the

unequal e x c h a n g e t h e o r y , the obstacle to justice in the world

economy is not only capital, b u t also labor in industrialized

countries.

Instead of r e o r g a n i z i n g their foreign economies to

meet NIEO demands, the industrialized countries re-emphasize

the unequal international division of l a b o r , although doing so

in new forms.

T h e s e are some of the q u e s t i o n s and h y p o t h e s e s to which

the p a p e r will a d d r e s s itself.

It will do so by r e v i e w i n g the

main NIEO i s s u e s according to the attention paid by v a r i o u s

g r o u p s to them, the political s u p p o r t for the NIEO p r i n c i p l e s ,

and the main o b s t a c l e s to Implementing the p r i n c i p l e s .

Information has been collected from a v a r i e t y of s o u r c e s ,

i n c l u d i n g public statements, statistical material, information

through unstructured interviews,

and o t h e r s .

With this

material the first section documents and d i s c u s s e s stated

policies on the NIEO g i v i n g special attention to the policies of

Norway and S w e d e n r e g a r d i n g the NIEO.

T h e selection of

Norway and Sweden seems to be warranted for other reasons

as w e l l .

Denmark has been a member of the European Community only since 1973; and Finland's and I c e l a n d ' s relations

with d e v e l o p i n g countries h a v e e v o l v e d much l e s s than those of

the o t h e r t h r e e .

In the second s e c t i o n , the main o b s t a c l e s to the NIEO in

the two Scandinavian c o u n t r i e s will be identified and d i s cussed.

In the third and final s e c t i o n , some alternative w a y s

are s u g g e s t e d that Scandinavian and like-minded c o u n t r i e s may

c o n s i d e r should multilateral n o r t h - s o u t h agreements on e s tablishing the NIEO not be .forthcoming.

48

WESTERN EUROPE AND THE NIEO

RELATIONS BETWEEN S C A N D I N A V I A N COUNTRIES

AND THE THIRD WORLD

Trade

High l e v e l s of e x p o r t s and imports, t a k e n as a share of g r o s s

national p r o d u c t , is a common feature of small industrialized

nations, s u c h as the Scandinavian c o u n t r i e s .

T h e y are open

economies, a c h a r a c t e r i s t i c t h e y s h a r e with many d e v e l o p i n g

countries.

The increase in Scandinavian foreign trade in the

period after 1960 w a s , h o w e v e r , not quite as s t r o n g as the

r e s t o f the w o r l d ' s (see table 4 . 1 ) .

Their countries' share of

world e x p o r t s was 4.5 p e r c e n t in 1 9 7 5 , as compared with 4.7

p e r c e n t in 1962.

In 1976 the total trade between Scandinavian

c o u n t r i e s and the T h i r d World amounted to $6.1 billion, of

which $5 billion was the s h a r e of import and e x p o r t .

Since 1960, Norway has had a substantial and steadily

i n c r e a s i n g import s u r p l u s in t r a d e with d e v e l o p i n g c o u n t r i e s .

In 1976, 11 p e r c e n t of the imports came from d e v e l o p i n g

c o u n t r i e s , and 12 p e r c e n t was e x p o r t e d to them. H o w e v e r , if

we ignore oil i m p o r t s , it a p p e a r s that the d e v e l o p i n g c o u n t r i e s '

s h a r e of N o r w a y ' s total imports declined from about 9 p e r c e n t

in 1960 to somewhat o v e r 6 percent in 1974.

This s h a r e is

v e r y low compared with the a v e r a g e for the industrialized

OECD c o u n t r i e s (approximately 19 p e r c e n t in 1 9 7 5 ) . .

In the case of S w e d e n , the, trade with d e v e l o p i n g c o u n t r i e s d e c r e a s e d d u r i n g the 1960s and the beginning of the

1970s.

From 1974, h o w e v e r , there h a s been a substantial

increase.

In 1976 the d e v e l o p i n g c o u n t r i e s ' part of Swedish

imports r e a c h e d 13 p e r c e n t and 14 p e r c e n t of e x p o r t s .

For

S w e d e n , e x p o r t s to d e v e l o p i n g c o u n t r i e s are as important as

e x p o r t s to North America, Japan, A u s t r a l i a , and New Zealand

put t o g e t h e r .

Developing c o u n t r i e s h a v e had a r e l a t i v e l y small share in

Finnish foreign t r a d e , v a r y i n g from 12 percent in the mid1950s to 6 p e r c e n t in the mid-1960s.

During the 1970s, the

d e v e l o p i n g c o u n t r i e s ' s h a r e has been steadily g r o w i n g .

This

c o n c e r n * first of all imports, which h a v e increased from 5.4

percent in 1970 to 11 p e r c e n t in 1977.

For all the Nordic

c o u n t r i e s s u c h i n c r e a s e s may be explained by the rise in the

price of o i l , although for Finland, oil imports from the Soviet

Union play an essential r o l e .

E x p o r t s to d e v e l o p i n g countries

have o n l y risen from 6.6 p e r c e n t in 1970 to 7 . 7 percent in

1977.

As an a v e r a g e for the Nordic c o u n t r i e s , trade with the

Third World in 1976 r e p r e s e n t e d 1 2 . 1 percent for imports and

1 1 . 0 p e r c e n t for e x p o r t s .

SCAN DIN A VIA/LIKE-MINDED COUNTRIES

49

Table 4 . 1 . The Stand of the Scandinavian C o u n t r i e s on

C o n c r e t e Proposals(a) P r e s e n t e d by the Group of 77

Developing C o u n t r i e s C o n c e r n i n g the New International

Economic O r d e r ( b )

(a) T h e enumeration is based on the following v o t e s :

on the economic r i g h t s and obligations of the s t a t e s :

A r t . 2a, 2b, and 2c, A r t . 6, A r t . 26.

Charter

A r t . 1,

T h e Lima declaration and the action program concerning

industrial development and cooperation: A r t . 1 9 , A r t . 32, A r t .

33, A r t . 47, A r t . 59 ( i ) . A r t . 60 (e) and ( f ) , A r t . 61 ( e ) ,

A r t . 76, on the whole declaration.

[Transnational C o r p o r a tions and Expansion of T r a d e in Manufactures and Semimanufactures, r e s . 9 7 ( i v ) , U N C T A D I V ] ,

(b)

T h e table is quoted from Holm, 1979, p. 5

Source:

Bo Huldt, T h e Nordic C o u n t r i e s and the NIEO: C o n s e n s u s and Dissension within the Nordic G r o u p , LuncTj

1978.

Report from the Danish delegation t o U N I D O ' s

Second General Conference In Lima March 12-26, 1975,

Copenhagen:

T h e Ministry of Foreign A f f a i r s , 1975.

P r o c e e d i n g s of the United Nations Conference on

T r a d e and Development, Fourth Session, Nairobi, May

5 - 3 1 , 1976, New Y o r k : United Nations. 1977.

50

WESTERN EUROPE AND THE NIEO

P O L I T I C A L AND C U L T U R A L RELATIONS

The e x t e n t of political relations with the T h i r d World is well

indicated by the establishment of permanent diplomatic missions.

In 1978, S w e d e n had permanent missions in 42,

Denmark in 35, Norway in 17 and Finland in 20 d e v e l o p i n g

countries.

Diplomatic missions are usually e s t a b l i s h e d in the

major t r a d i n g p a r t n e r c o u n t r i e s and the major r e c i p i e n t s of

development a s s i s t a n c e and cooperation.

During the 1970s there was a rapid g r o w t h in Nordic

diplomatic missions in the Near E a s t .

The trend may be

explained by the i n c r e a s e d political and economic influence of

the oil p r o d u c i n g c o u n t r i e s .

T h i s explanation also applies to

the g r o w i n g number of diplomatic missions in other p a r t s of

the w o r l d .

T h e r e l a t i v e l y low number of permanent missions

for Norway and Finland is to some e x t e n t offset by a high

number of non-permanent diplomatic missions and by a c creditation to n e i g h b o r i n g c o u n t r i e s .

The Nordic c o u n t r i e s

t h u s h a v e established diplomatic relations with most of the

developing countries.

B e s i d e s a g r e e m e n t s with some Mediterranean c o u n t r i e s and

with India, C u b a , and C h i n a , c u l t u r a l relations with d e veloping c o u n t r i e s is still poorly d e v e l o p e d .

T h i s may be offset to some e x t e n t by more intense

cultural e x c h a n g e s in the p r i v a t e and semi-public s e c t o r s .

Radio and television in all Nordic c o u n t r i e s are a state-owned

monopoly i n s t i t u t i o n .

The s h a r e of n e w s and c u l t u r a l l y

relevant programs concerning developing countries, produced

by institutions or i n d i v i d u a l s in these c o u n t r i e s , is not g r e a t ,

however.

NIEO-RELATED POLICIES OF THE S T A T E AND MAIN

INTEREST GROUPS

General Positions

All five Nordic c o u n t r i e s have stated their g e n e r a l support for

NIEO p r i n c i p l e s in multilateral e n c o u n t e r s , notably in the

United

Nations.

Sweden

had

been the most o u t s p o k e n

Scandinavian c o u n t r y in s u p p o r t i n g NIEO demands d u r i n g the

first round of c o n f e r e n c e s d u r i n g the period of 1974-1976,

followed closely by N o r w a y .

Denmark was somewhat more

reticent.

T h i s p a t t e r n was r e v e a l e d in a s t u d y of Nordic voting

behavior in almost 20 roll-calls at t h r e e different s e s sions.(1,2)

After a period of e a r l y e n t h u s i a s m , h o w e v e r ,

d i f f e r e n c e s between the countries have become smaller in

SCAN DIN A VIA/LIKE-MINDED COUNTRIES

51

recent y e a r s .

What most likely has h a p p e n e d is that the

S w e d i s h and Norwegian " p r o g r e s s i v e spirit" has been mode r a t e d , a function both of e x t e r n a l factors - the political and

economic c r i s e s - and the way important factions of the

economic i n t e r e s t g r o u p s and public opinion h a v e reacted to

the NIEO m e s s a g e .

All five countries h a v e s t r e s s e d , in v a r i o u s forms, their

support for i n t e r d e p e n d e n c e , their own role of a mediator, and

their willingness to make concessions and cooperate without

political s t r i n g s a t t a c h e d .

It is thus probably c o r r e c t to say

that their policies, as they like to draw them, are not only

more p r o g r e s s i v e than those of most of the other industrialized

c o u n t r i e s , but also somewhat more incoherent.

T h e best

example of i n c o h e r e n c e is probably found in official Norwegian

policy.

In what is still the main e x p r e s s i o n of state policy

toward the d e v e l o p i n g countries in Norway, Parliamentary

Report no. 94 ( 1 9 7 4 - 7 5 ) , on N o r w a y ' s economic dealings with

d e v e l o p i n g c o u n t r i e s , a d e p e n d e n c y relationship is reflected

when it is stated that the d e v e l o p i n g countries

still find themselves in a position of economic

d e p e n d e n c e on the rich part of the world t h r o u g h a

system of ownership c o n t r o l , division of labour and

power which e f f e c t i v e l y p r e v e n t s them from attaining

full economic and social i n d e p e n d e n c e ,

( p . 9)

A similar, b u t l e s s p r o n o u n c e d , view is e x p r e s s e d by the

S w e d i s h government in its r e p o r t ,

Guidelines for S w e d e n ' s

international development policy ( 1 9 7 8 ) , where it is stated that

for Sweden it is s e l f - e v i d e n t that we must

acknowledge the fundamental lack of balance in

the relationship between poor and rich c o u n t r i e s ,

( p . 73)

In the Norwegian parliamentary r e p o r t , t h e r e is also manifest

s u p p o r t of the view that there is a causal relationship between

development and wealth in the n o r t h , underdevelopment and

p o v e r t y in the s o u t h .

In many w a y s we (Norway) are reaping the

benefits of an economic system which s e t s its mark

on the relations between the rich and the poor

c o u n t r i e s , ( p . 13)

and the r e p o r t g o e s on to criticize the p r e s e n t o r d e r in rather

unmistakable terms:

It is r e c o g n i z e d that the e x i s t i n g international

economic s y s t e m p r o d u c e s e f f e c t s which are d e t r i -

52

WESTERN EUROPE AND THE NIEO

mental to the l e s s d e v e l o p e d c o u n t r i e s .

T h e free

market mechanism h a s not led to equitable r e s u l t s ,

but has on the c o n t r a r y s e r v e d to widen the

d i s p a r i t y between the r i c h and the poor c o u n t r i e s ,

( p . 26)

T h i s s t r u c t u r a l - s y s t e m i c c r i t i q u e is not e x p r e s s e d as clearly

by any of the o t h e r Nordic c o u n t r i e s .

It has r e a p p e a r e d in

the S w e d i s h Social Democratic P a r t y ' s statement on the Swedish

Guidelines and in later statements by Norwegian o f f i c i a l s . One

g e t s the impression, h o w e v e r , that the s t r u c t u r a l - s y s t e m i c

critique has b e e n modified o v e r the last two or t h r e e y e a r s ,

e s p e c i a l l y in N o r w a y .

I n s t e a d , more emphasis is put on the

need for internal r e d i s t r i b u t i o n initiated by n e c e s s a r y s o c i o political reforms in the d e v e l o p i n g c o u n t r i e s t h e m s e l v e s .

But

instead of siding e n t i r e l y with those r e p r e s e n t a t i v e s of

d e v e l o p e d c o u n t r i e s who h a v e c o n c e n t r a t e d on the i s s u e s of

basic n e e d s - a p p a r e n t l y p a r t l y in o r d e r to deliberately weaken

the NIEO demands - they a r e t r y i n g to s t r i k e a balance

between the NIEO and basic needs p o l i t i c k i n g .

In the words

of the S w e d i s h g o v e r n m e n t

We must continue to g i v e s t r o n g s u p p o r t to the

ideas behind a new international economic o r d e r , at

the same time as we stick to the demand that improvements (internationally) should be at the benefit

of the poor p e o p l e ,

( p . 73)

T h i s is worded more s t r o n g l y by the S w e d i s h Social Democrats,

p r e s e n t l y in opposition, in terms of a c r i t i q u e :

T h e unjust d i s t r i b u t i o n of power and r e s o u r c e s

in d e v e l o p i n g c o u n t r i e s (is) part of the inequality more to those who already h a v e - which the i n t e r national capitalist s y s t e m e n f o r c e s .

( p . 3 in Motion

1 9 7 7 / 7 8 , 1912)

T h e emphasis on mass-oriented development s t r a t e g i e s in the

d e v e l o p i n g c o u n t r i e s is not a new idea to the Nordic g o v e r n ments.

Since the e a r l y 1970s the S w e d e s , and later the

N o r w e g i a n s , h a v e s t r e s s e d that development aid policies should

f a v o r c o u n t r i e s which c o n d u c t a "socially just" s t r a t e g y of

r e d i s t r i b u t i o n , and that special emphasis is to be put on

development actions which favor the poorest s t r a t a .

Thus

their emphasis on domestic development p r o g r a m s is based on

political decisions taken before the NIEO became an i s s u e ,

although t h e r e may h a v e been some c h a n g e of v o c a b u l a r y and

emphasis since the NIEO was offset by the s t r a t e g y r e g a r d i n g

basic n e e d s by the Western p o w e r s .

SCAN

DIN

A

VIA/LIKE-MINDED

COUNTRIES

53

Both Finland and Denmark h a v e taken part in d i s c u s s i o n s

c o n d u c t e d within the like-minded industrialized c o u n t r i e s .

T h e y h a v e , h o w e v e r , been r a t h e r p a s s i v e p a r t n e r s ; the core

of the g r o u p has remained the N e t h e r l a n d s , S w e d e n , and

Norway.

Danish participation is conditioned by the e x t e n t to

which the Netherlands and Belgium, two members of the

like-minded g r o u p that are also members of the E E C , can side

with like-minded p o s i t i o n s .

As these two c o u n t r i e s seem to

h a v e moderated their a c t i v e i n t e r e s t in the like-minded g r o u p ,

Denmark also has taken l e s s i n t e r e s t .

Denmark's position on the NIEO has been influenced

mainly by t w o , p o s s i b l y t h r e e , f a c t o r s : the economic c r i s i s ;

the need to accommodate to a n d , in case of a conflict of

i n t e r e s t , to follow the EC p o l i c y ; and a somewhat unstable

parliamentary situation.

T h e Danish s u p p o r t of the Common

Fund in Nairobi, for example, was full of r e s e r v a t i o n s , (3)

despite the fact that it is in Denmark's interest to a c h i e v e

s t a b l e p r i c e s on vital raw material imports.

Denmark, howe v e r , is a s t r o n g s u p p o r t e r of free trade regimes in i n t e r n a tional t r a d e and has i n d i r e c t l y sided with the developing

c o u n t r i e s in p r o t e s t i n g great power protectionism on manufactured g o o d s .

Danish r e p r e s e n t a t i v e s have been more

d o w n - t o - e a r t h in their public statements than their Swedish

and Norwegian c o u n t e r p a r t s , s t r e s s i n g the need for go-slow

implementation of the NIEO p r o p o s a l s , in o r d e r not to c a u s e

economic harm to the industrialized world, and pointing out

that Denmark itself only c o n c e d e s to d e v e l o p i n g c o u n t r i e s '

demands at the v e r y optimum of its economic c a p a c i t y .

As one

o b s e r v e r commented.

It

is

somewhat

surprising

that

conference

speeches

(of

Danish

officials)

clearly manifest

specific Danish i n t e r e s t s .

One should think that the

o p p o r t u n i t y to get s t a t u s and an improved s t a n d i n g

would make these statements more v a l u e - p r o m o t i v e ,

more dominated by ideology than they p r o v e to

be.(4)

T h e political instability is only r e l a t i v e ; compared with most

o t h e r c o u n t r i e s , Denmark is a stable p o l i t y .

The t u r n o v e r of

g o v e r n m e n t s in Denmark, h o w e v e r , is g r e a t e r than in Sweden

and N o r w a y , although much l e s s than in Finland.

More

importantly, the social problems seem g r e a t e r due to an

unemployment rate of about 10 p e r c e n t .

T h i s further e x p l a i n s

the r e l a t i v e s e l f - i n t e r e s t in Danish NIEO p o l i c i e s .

One recent and quite o u t s p o k e n e x p r e s s i o n of this

s e l f - i n t e r e s t are the proposals of the Federation of Danish

I n d u s t r i e s for a closer link between aid and trade policies and

the i n t e r e s t s of i n d u s t r y .

T h e Federation ( I n n d u s t r i e n og

u - l a n d e n e , 1977) p r o p o s e s that Danish development aid be used

54 WESTERN EUROPE AND THE NIEO

to promote Danish i n d u s t r y ' s s e a r c h for new markets and its

participation in the industrialization of d e v e l o p i n g c o u n t r i e s .

In o r d e r to make this p o s s i b l e , the Federation p r o p o s e s that

aid e x t e n d e d t h r o u g h the United Nations s y s t e m be cut by

half, so that loans and c r e d i t s to finance the p u r c h a s i n g of

g o o d s in Denmark, and Danish participation in industrialization

p r o j e c t s of the d e v e l o p i n g c o u n t r i e s can be i n c r e a s e d .

This,

a c c o r d i n g to the Federation, would create employment in

Denmark, improve balance of payments and s u p p o r t "the

Danish i n d u s t r y ' s natural Interest in gaining a foot-hold in

developing countries."

As one commentator points o u t , these

p r o p o s a l s attempt to link the i n t e r e s t s of Danish i n d u s t r y and

capital to the NIEO t a r g e t of a 25 p e r c e n t s h a r e for d e v e l o p i n g

c o u n t r i e s in world industrial production by the y e a r 2000.

T h e y do t h i s , h o w e v e r , in a narrow p e r s p e c t i v e and t h r o u g h

an outmoded perception of development g o a l s .

At the same

time they reject a number of o t h e r NIEO principles s t r o n g l y

b a c k e d b y d e v e l o p i n g c o u n t r i e s . (5)

Finland's position is influenced by an o v e r r i d i n g foreign

policy c o n c e r n d e r i v e d from East-West p o l i t i c s , that i s , to

r e d u c e international t e n s i o n s .

Its position u n d e r w e n t c h a n g e s

in the mid-70s, as a d i r e c t r e s u l t of the oil c r i s i s . (6) In the

fall of 1974, the Finnish government p u b l i s h e d the "Program of

Principles for International Development C o o p e r a t i o n . "

The

r e p o r t r e f l e c t s the g r o w i n g emphasis in the OECD c o u n t r i e s on

i n t e r d e p e n d e n c e and " c r i s i s management" as a r e s p o n s e to the

e v e n t s of 1 9 7 3 - 1 9 7 4 .

T h i s is further d e v e l o p e d in the report

of the State Committee for Development Cooperation ( 1 9 7 8 ) .

T h e r e p o r t notes that Finland, for i t s own economic i n t e r e s t s

as well as in the name of international p e a c e , must take a

positive s t a n d toward the NIEO.

On a continuum Finnish

policy seems c l o s e r to the Danish 'national i n t e r e s t s ' than to

the S w e d i s h and Norwegian p r i n c i p l e d and more ideologically

motivated s t a n d .

Finland's policy on NIEO i s s u e s a p p e a r s

d i c t a t e d by trade and i n d u s t r i a l r e l a t i o n s ; the chemical and the

woodpulp i n d u s t r i e s b e i n g p a r t i c u l a r l y influential.

Development aid still is v e r y modest in volume and g e o g r a p h i c a l

e x t e n s i o n , b u t the g o v e r n m e n t seems to emphasize the role of

aid as p a r t of the S c a n d i n a v i a n - N o r d i c c o n t r i b u t i o n .

In that

s e n s e , Finland a c t s as a " f r e e - r i d e r " : It benefits from the

positive image which Nordic aid g e t s internationally, b u t does

not c o n t r i b u t e much to the creation of that image. (7)

It may

be a recognition of this that prompted the Committee to

p r o p o s e to double the volume of aid by 1982, and the g o v e r n ment to a c c e p t this in p r i n c i p l e .

Finnish i n d u s t r y t a k e s a mixed view of the NIEO i s s u e s .

It has adopted a r a t h e r n e g a t i v e position on the I n t e g r a t e d

Program of Commodities and the Common F u n d . I t s v i e w s of

the Code of C o n d u c t on T e c h n o l o g y seem p o s i t i v e , h o w e v e r ,

b e c a u s e Finland, as a net importer of t e c h n o l o g y , h a s a com-

SCAN DIN A VIA/LIKE-MINDED COUNTRIES 55

mon interest in this area with d e v e l o p i n g c o u n t r i e s .

When

it comes to r e s t r u c t u r i n g and market a c c e s s , h o w e v e r , the

i n d u s t r y ' s position is not clear b e c a u s e of internal c o n t r a dictions between home m a r k e t - o r i e n t e d and t r a d e or foreign

production-oriented industries.

T h e r e is a mixed attitude

toward protectionism and internationalization as well.

T h e most

dynamic s e c t o r s (those that are the most e x p o r t - o r i e n t e d )

seem, h o w e v e r , to favor a S w e d i s h - t y p e position in the "new

international division of l a b o r . " (8)

Iceland lacks the r e s o u r c e s n e c e s s a r y to take an a c t i v e

p a r t in the NIEO d i s c u s s i o n s at t h e level of the other Nordic

countries.

Iceland was hit much more s t r o n g l y and much

e a r l i e r by the international economic c r i s i s .

Its trade with

d e v e l o p i n g c o u n t r i e s is c o n c e n t r a t e d in e x p o r t i n g fish and fish

p r o d u c t s and importing raw materials and o i l .

Its aid program

was initiated in the b e g i n n i n g of the 1970s, h a v i n g been

d i s c u s s e d since 1965.

In 1977, total appropriations reached

0.6 million US d o l l a r s .

T h i s made Iceland for the first time a

net c o n t r i b u t o r of development a i d .

Until 1976, Iceland itself

r e c e i v e d a i d , mainly t h r o u g h UNDP.

Aid for the period

1 9 7 1 - 1 9 7 6 amounted to $1 million. A similar amount had been

e n v i s a g e d for the period 1977-1982, but in December 1976 the

Icelandic g o v e r n m e n t d e c l a r e d it would no l o n g e r a s k for

f o r e i g n economic a s s i s t a n c e of this k i n d . Since 1973, a small

part of Iceland's ODA is channeled t h r o u g h the joint Nordic

aid p r o g r a m , e s t a b l i s h e d by an agreement in Oslo In the same

year.

P r i v a t e Icelandic investments in d e v e l o p i n g c o u n t r i e s

are not k n o w n .

Industrialization

All the Nordic c o u n t r i e s h a v e a c c e p t e d the principle of r e s t r u c t u r i n g their own economic s y s t e m s and the Lima target for

T h i r d World industrialization, although in v a r y i n g d e g r e e s and

forms.

In this s e c t i o n , the position of Norway and Sweden

will be r e v i e w e d with p a r t i c u l a r emphasis on the i n d u s t r i a l i zation of d e v e l o p i n g c o u n t r i e s , market a c c e s s for manufactured

p r o d u c t s from d e v e l o p i n g c o u n t r i e s , and r e s t r u c t u r i n g in the

S c a n d i n a v i a n countries within that c o n t e x t .

As already noted, S w e d i s h manufacturers are deeply

i n v o l v e d in production and marketing in a number of d e veloping c o u n t r i e s .

T h e r e is a clear t e n d e n c y in the o t h e r

c o u n t r i e s , i n c l u d i n g N o r w a y , to copy the " S w e d i s h p a t t e r n , "

although conceptions of how this should be done v a r y .

N o r w a y ' s official position on the principle of international

r e s t r u c t u r i n g is as positive as the S w e d i s h o n e , but is less

concrete.

Development aid has so far not been channeled to

promote T h i r d World industrialization, e x c e p t for funds which

a r e e x t e n d e d to firms making pre-investraent s t u d i e s and those

56

WESTERN EUROPE AND THE NIEO

s e e k i n g g u a r a n t e e s against economic r i s k s .

Until r e c e n t l y ,

these facilities h a v e b e e n little u s e d b y Norwegian i n d u s t r y .

In r e p o r t 94, the g o v e r n m e n t r a i s e d the idea of c r e a t i n g

another c r e d i t facility which was to be financed by public

g r a n t s in e x c e s s of the official 1 p e r c e n t of GNP t a r g e t for

development aid a p p r o p r i a t i o n s .

T h i s facility was to finance

industrial cooperation p r o j e c t s of an experimental n a t u r e .

The

Norwegian s t a t e was not to assume a d i r e c t role in s u c h

projects,

but inter alia finance the r e s p e c t i v e d e v e l o p i n g

c o u n t r y ' s s h a r e in the e q u i t y capital and p r o v i d e the r e s t of

the capital as n e e d e d .

As appropriations for development aid

had to be flattened out in 1978 due to s t a g n a t i n g income from

oil production and a mounting domestic economic c r i s i s , this

scheme was postponed until 1 9 7 9 . T h e n Parliament adopted i t ,

v o t i n g a first installment of 50 million Norwegian k r o n e r .

T h e r e i s , h o w e v e r , i n c r e a s i n g Norwegian a c t i v i t y r e g a r d i n g the e x p o r t s o f manufactured g o o d s , including capital

g o o d s , to aid the industrialization of d e v e l o p i n g c o u n t r i e s .

T h e state has i n c r e a s e d the volume of e x p o r t c r e d i t s and

s u b s i d i e s c o n s i d e r a b l y in o r d e r to finance s u c h e x p o r t s and to

a s s i s t in obtaining c o n t r a c t s .

T h i s p e r t a i n s in p a r t i c u l a r to

the e x p o r t of s h i p s , which are financed t h r o u g h special

guarantee schemes,

to help p r e s e r v e employment in the

crisis-stricken shipyard industry.

T h e Norwegian Association of I n d u s t r i e s , in a comment on

Government R e p o r t 94,

p r o p o s e s the establishment of a

Norwegian industrialization fund for d e v e l o p i n g c o u n t r i e s and

s u g g e s t s a g r e a t e r role for Norwegian i n d u s t r i e s , p r o v i d e d the

r i g h t i n c e n t i v e s are made a v a i l a b l e .

T h e s e i n c e n t i v e s include

r i s k c a p i t a l , more t y i n g of aid to p u r c h a s e s of Norwegian

capital goods as well as o t h e r goods and s e r v i c e s , and state

s u p p o r t of p r i v a t e

Norwegian

i n v e s t m e n t s in d e v e l o p i n g

countries.

T h e Association also o p p o s e s the g o v e r n m e n t ' s

proposal to limit industrialization a s s i s t a n c e to the least

d e v e l o p e d c o u n t r i e s and those ten or so d e v e l o p i n g c o u n t r i e s

that a l r e a d y r e c e i v e aid from N o r w a y .

It s u g g e s t s that state

s u p p o r t to industrialization be e x t e n d e d to o t h e r , more e c o nomically d e v e l o p e d c o u n t r i e s in the s o u t h , where t h e r e are

p r i v a t e Norwegian i n v e s t m e n t s . T h e Association maintains that

o t h e r i n d u s t r i a l i z e d c o u n t r i e s a r e g i v i n g more state s u p p o r t to

their i n d u s t r i e s ' a c t i v i t i e s in the s o u t h ; that most of the

m u l t i - b i - a s s i s t a n c e ( s u c h as UNDP funds) to which S c a n dinavian c o u n t r i e s are major c o n t r i b u t o r s , a r e b e i n g channeled

to i n d u s t r i e s in o t h e r i n d u s t r i a l i z e d c o u n t r i e s ; and that for

both these r e a s o n s the state o u g h t to i n t e r v e n e to s e c u r e more

c o n t r a c t s and e x p o r t s for Norwegian companies.

The general

view of the Association c o r r e s p o n d s to the concept of a "new

international division of l a b o r " : l e s s economically profitable

and l a b o r - i n t e n s i v e , t e c h n o l o g y - e x t e n s i v e industrial a c t i v i t i e s

should be t r a n s f e r r e d to d e v e l o p i n g c o u n t r i e s , while Norwegian

SCANDINAVIA/LIKE-MINDED COUNTRIES

57

i n d u s t r y should c o n c e n t r a t e on t h e more profitable, a d v a n c e d technology areas.

S w e d e n established a Fund for industrial cooperation with

d e v e l o p i n g c o u n t r i e s in 1978, with an anticipated b a s i s capital

of 100 million S w e d i s h k r o n e r .

T h e p u r p o s e of the fund is to

s u p p o r t p r o c e s s i n g i n d u s t r y projects in developing countries

which h a v e "a positive development effect in the c o u n t r y .

Special emphasis should be placed on the employment e f f e c t . "

( G u i d e l i n e s , p. 121)

Small and medium-sized projects are

e s p e c i a l l y singled o u t , b u t o t h e r w i s e there are no particular

conditions to be met.

O b v i o u s l y , S w e d i s h firms are to be

g i v e n priority when contract p a r t n e r s are s e l e c t e d .

The Fund

is to become an i n d e p e n d e n t s h a r e - h o l d i n g company which can

own s h a r e s in projects in d e v e l o p i n g countries with the

p u r p o s e of t r a n s f e r r i n g o w n e r s h i p (of at least the Fund's own

s h a r e ) to the local government or its a g e n t .

Unlike N o r w a y , Sweden h a s long p r a c t i c e d a policy of

e x t e n d i n g development aid for industrialization p r o j e c t s .

Aid

for projects in the manufacturing s e c t o r accounted to 33

p e r c e n t of total S w e d i s h public aid in 1976-1977, against only 2

p e r c e n t in 1 9 7 0 - 1 9 7 1 .

In addition, e x p o r t c r e d i t s to finance

the p u r c h a s e of equipment and capital goods in Sweden i n c r e a s e d r a p i d l y . A considerable number of Swedish firms h a v e

taken p a r t in the e x p o r t c r e d i t a r r a n g e m e n t s .

The newly

e s t a b l i s h e d Fund will c o v e r an aspect that has been mostly

a b s e n t from e x p o r t credit arrangements so far: the possibility

of e n g a g i n g S w e d i s h firms d i r e c t l y in d e v e l o p i n g countries in

joint v e n t u r e s s u p p o r t e d b y the S w e d i s h s t a t e .

Market A c c e s s

All the Nordic c o u n t r i e s are members of OECD and G A T T ;

Denmark is a member of the E C ; I c e l a n d , Norway and Sweden

a r e members of EFT A.

Finland is an associated member of

EFTA and has an agreement with CMEA. T h e s e commitments

s t r o n g l y influence their trade policy toward d e v e l o p i n g c o u n tries.

Norway and S w e d e n in addition h a v e free trade

agreements with the EC which means that they are part of a

trade system which is p r a c t i c a l l y free of customs b a r r i e r s for

manufactured g o o d s .

T h e s e formal commitments are as important in explaining

r e s t r i c t i v e policies toward d e v e l o p i n g c o u n t r i e s as are the

w e i g h t of domestic i n t e r e s t g r o u p s . I n d u s t r i e s like textile and

clothing are fighting against both f a c t o r s , since imports from

OECD c o u n t r i e s account for the lion's s h a r e of global textile

and clothing imports.

But it is imports from developing

c o u n t r i e s and Hong K o n g which are the most affected b e c a u s e

no international multilateral commitments, i n v o l v i n g a s e r i o u s

potential for retaliation, p r e v e n t g o v e r n m e n t s from taking

protectionist m e a s u r e s .

58

WESTERN EUROPE AND THE NIEO

T h e Danish l e a d e r s h a v e o p e n l y s t r e s s e d the free trade

principle in their comments on the NIEO.

T h i s s u p p o r t of a

p r i n c i p l e , which in fact all the Nordic c o u n t r i e s h a v e f a v o r e d ,

is not v e r y well matched in p r a c t i c e .

In a s t u d y of import

r e s t r i c t i o n s applied by OECD c o u n t r i e s on 49 p r o d u c t s or

p r o d u c t g r o u p s of p a r t i c u l a r i n t e r e s t to d e v e l o p i n g c o u n t r i e s ,

the UNCTAD S e c r e t a r i a t r a n k s Denmark as the most r e s t r i c t i v e

of the . four Nordic c o u n t r i e s .

Since the c o u n t r i e s of the

European Community are the most r e s t r i c t i v e in the o v e r a l l

r a n k i n g , EC membership must h a v e influenced Denmark's policy

toward d e v e l o p i n g c o u n t r i e s in the direction of g r e a t e r

protectionism.

( U N C T A D , 1979, T D / 2 2 9 / S u p p 2 , p . 26)

Like o t h e r Nordic c o u n t r i e s , Norway has introduced its

own G S P .

T h e s y s t e m , which was i n t r o d u c e d i n 1 9 7 1 , had

only marginal e f f e c t s on t r a d e . It i n c r e a s e d the p e r c e n t a g e of

manufactured imports from developing c o u n t r i e s exempt from

import tariffs from 92 u n d e r the p r e - 1 9 7 1 G A T T arrangement

to 96 to 9 7 . S t i l l , the GSP s y s t e m c o v e r e d only 2.5 p e r c e n t of

N o r w a y ' s total imports from d e v e l o p i n g c o u n t r i e s , and 83

p e r c e n t of imports u n d e r the GSP came from only 9 c o u n t r i e s ,

mostly n e w l y industrialized o n e s .

T h e s y s t e m has t h u s only

s l i g h t l y c o n t r i b u t e d to i n c r e a s i n g the s h a r e of manufactured

p r o d u c t s in N o r w a y ' s imports from d e v e l o p i n g c o u n t r i e s .

The

s h a r e rose from 6 p e r c e n t in 1961 to 16 p e r c e n t in 1 9 7 7 .

During the "oil boom," the Norwegian government p r o p o s e d more a c t i v e utilization of the GSP and i n t r o d u c e d a

s p e c i a l office in the Ministry of T r a d e to promote imports from

d e v e l o p i n g c o u n t r i e s (NORIMPOD). T h e p u r p o s e of the office

was to r e d u c e some of the nontariff trade b a r r i e r s .

The effect

h a s been v e r y limited.

Norwegian home market i n d u s t r i e s

acted to p r e v e n t imports of d i r e c t l y competing p r o d u c t s .

T e x t i l e and clothing are thus not included in the G S P , and the

government has to set a global quota for imports from d e veloping countries in this s e c t o r .

It is mostly "exotic"

p r o d u c t s that h a v e been promoted by NORIMPOD.

T h e policy d u r i n g the mid-70s was based on the e x pectations of a f u r t h e r oil boom.

T h e Norwegian labor market

was e x p e c t e d to be extremely t i g h t , t h u s favoring domestic

r e s t r u c t u r i n g and the t r a n s f e r of labor into new j o b s .

A

controlled p h a s i n g - o u t of some s e c t o r s , s u c h as textile and

c l o t h i n g , was e n v i s a g e d .

E x p o r t s were not to be s t r o n g l y

promoted b e c a u s e there would be a s u r p l u s of capital a n y w a y ,

which would h a v e to be e x p o r t e d . T h e s e e x p e c t a t i o n s did not

materialize; instead an a d v e r s e trend in trade coupled with

rising unemployment o c c u r r e d , and Norwegian economic policy

was r e v e r s e d .

From 1976 and 1977 o n , emphasis was no

longer on stimulating imports from d e v e l o p i n g c o u n t r i e s , b u t

on exporting.

S w e d e n has p r a c t i c e d a policy of trade liberalism which

h a s r e s u l t e d in lower tariffs than in most o t h e r industrialized

SCAN DIN A VIA/LIKE-MINDED COUNTRIES

59

countries.

Free trade agreement with the EC h a s , as in the

case of N o r w a y , f u r t h e r lowered tariffs for trade with Western

Europe.

Swedish policy toward d e v e l o p i n g c o u n t r i e s i s v e r y

similar to that of N o r w a y .

It is p a r t l y a r e s u l t of Swedish

i n d u s t r y ' s foreign production p o l i c y .

T h e Swedish GSP s y s t e m contains p r o t e c t i v e c l a u s e s and

does not c o v e r the most competitive d e v e l o p i n g c o u n t r y

p r o d u c t s , notably t e x t i l e , c l o t h i n g , and l e a t h e r .

It is, as

with N o r w a y , h e a v i l y c o n c e n t r a t e d on the newly industrialized

s t a t e s : nine c o u n t r i e s accounted for 86 p e r c e n t of imports

under the GSP s y s t e m in 1974.

P r o d u c t s , which d e v e l o p i n g

c o u n t r i e s h a v e a comparative a d v a n t a g e , face e f f e c t i v e tariffs

of up to 60 p e r c e n t . ( 9 )

S t i l l , these seem not to be p a r t i c ularly h i g h compared with tariffs and r e s t r i c t i v e measures

imposed b y other i n d u s t r i a l i z e d c o u n t r i e s .

In some b r a n c h e s , the import s h a r e of the S w e d i s h market

is as high as 90 p e r c e n t .

In the case of clothing it is 75

p e r c e n t on the a v e r a g e .

Only 10 to 15 p e r c e n t , h o w e v e r ,

comes from d e v e l o p i n g c o u n t r i e s and Hong K o n g . A g r e a t deal

comes t h r o u g h affiliates of S w e d i s h companies in Finland and

Portugal - comparatively l o w - c o s t c o u n t r i e s in the OECD

group.

It has been estimated that 29 p e r c e n t of Swedish

e x p o r t g o e s a s inter-company t r a n s f e r s , i . e . , t h r o u g h S w e d i s h

t r a n s n a t i o n a l ( U N C T A D S e c r e t a r i a t , 1 9 7 6 ) . We h a v e no data

to indicate whether inter-company t r a n s f e r s are more or l e s s

dominant in S w e d e n ' s economic e x c h a n g e s with d e v e l o p i n g

c o u n t r i e s than the a b o v e p e r c e n t a g e s h o w s .

A logical a s sumption, h o w e v e r , is that e x p o r t s from Sweden are more tied

to s u c h t r a n s f e r s than Imports to S w e d e n .

Domestic R e s t r u c t u r i n g

As a c o n s e q u e n c e of g e n e r a l developments in s o c i e t y , and the

c h a n g e s in the p r o d u c t i v e s y s t e m s that h a v e favored c e n t r a l ization (rationalization and urbanization) all Nordic c o u n t r i e s

h a v e u n d e r g o n e a fundamental r e s t r u c t u r i n g o v e r the last

decades.

T h i s trend has p r o b a b l y been most prominent in

S w e d e n , w h e r e migration from the c o u n t r y s i d e has been a c t i v e

to s u p p l y labor to a rapidly g r o w i n g manufacturing i n d u s t r y

and s e r v i c e s e c t o r . In N o r w a y , d u e to the p a r t i c u l a r emphasis

on fisheries and small-scale farming, the trend has been much

l e s s prominent.

R e g a r d i n g their policies on NIEO demands for industrial

c o u n t r y r e s t r u c t u r i n g , Norway seems to h a v e modified its

initial favorable attitude at the state l e v e l .

T h e Foreign

Ministry in 1977 p r e p a r e d an internal s t u d y that ended up

proposing a fund for financing domestic industrial readjustment

r e s u l t i n g from the i n c r e a s e d imports of goods from d e v e l o p i n g

countries.

T h e s t u d y was a follow-up of the principles set

60

WESTERN EUROPE AND THE NIEO

down in Report n o . 94, on future industrial policies (19741 9 7 5 ) , and of e x p e c t a t i o n s of a tight labor market as a r e s u l t

of the oil boom.

The s t u d y s u g g e s t e d that the role of s u c h a

fund should be to finance e x t r a financial o u t l a y s as a r e s u l t of

lost employment, while the companies c o n c e r n e d work out

a l t e r n a t i v e employment o p p o r t u n i t i e s .

T h e s t u d y was not

e n d o r s e d politically, a p p a r e n t l y b e c a u s e of opposition from

both the Association of I n d u s t r i e s and the Federation of Labor

(LO).

In a r e c e n t s t u d y , no clear t r e n d in p r e s e n t Norwegian

policy was r e p o r t e d . ( 1 0 )

It seems fair to s a y that the i n tentions of g o v e r n m e n t , as e x p r e s s e d in Report n o . 94, and

later r e p e a t e d in i t s long-term program for 1 9 7 8 - 1 9 8 1 , h a v e

been p u t on i c e .

Instead of the planned i n c r e a s e in manufactured imports from d e v e l o p i n g c o u n t r i e s and g r a d u a l r e adjustment at home, import i n c r e a s e s are b a r r e d and g r e a t e r

emphasis is put on promoting e x p o r t s to the Third World.

T h i s t a k e s place p a r t l y in o r d e r to make up for s t a g n a t i n g or

decreasing exports to developed countries.

Present policies

for e x p o r t e x p a n s i o n to T h i r d World c o u n t r i e s are based on

two broad m e a s u r e s : special g u a r a n t e e s against political and

commercial r i s k s in connection with e x p o r t s of capital (which is

still little u s e d ) , and s u b s i d i e s on i n t e r e s t s in connection with

export credits.

T h e l a t t e r h a s been e x t e n s i v e l y used t o g e t

c o n t r a c t s on e x p o r t s of s h i p s to d e v e l o p i n g c o u n t r i e s , i n v o l v i n g state g u a r a n t e e s to the s h i p y a r d i n d u s t r y which

p r e s e n t l y totals 2.5 billion Norwegian k r o n e r .

In S w e d e n , readjustment and r e s t r u c t u r i n g are d i s c u s s e d

as economic, commercial n e c e s s i t i e s , independent of the NIEO.

Until the b e g i n n i n g of the 1960s, S w e d e n ' s position in the

international division of labor was c h a r a c t e r i z e d by production

based on domestic raw materials, with a high d e g r e e of

p r o c e s s i n g and h i g h l y capital i n t e n s i v e e x p o r t s e c t o r s .

During

the 1960s this position was transformed into a more and more

labor i n t e n s i v e p r o d u c t i o n , ( 1 1 )

I n d u s t r y and its spokesmen

want this trend to c o n t i n u e .

A c c o r d i n g to the v i e w s of the

e x p o r t - o r i e n t e d , internationalized s e c t o r s , not only the l a b o r i n t e n s i v e i n d u s t r i e s ( t e x t i l e , l e a t h e r , e t c . ) but e v e n those

p a r t s of the e x p o r t i n d u s t r i e s that still produce from local raw

materials and with r e l a t i v e l y unsophisticated technology ( p a r t s

o f the s t e e l , p a p e r , s h i p y a r d i n d u s t r y , e t c . ) should move

production a b r o a d .

T h e s e are i n d u s t r i e s in c r i s i s which seem

to s u r v i v e only b e c a u s e the state has i n t e r v e n e d h e a v i l y to

s u p p o r t them.

If t h e s e t r e n d s are not related to demands for a NIEO,

the NIEO i s s u e may n e v e r t h e l e s s become linked with them.

Location of production abroad may be defended against p r o t e s t s from w o r k e r s in S w e d e n , by r e f e r e n c e to the demands of

d e v e l o p i n g c o u n t r i e s e v e n t h o u g h the real motive behind the

t r a n s f e r is i n c r e a s i n g p r o f i t a b i l i t y .

On the o t h e r h a n d , the

SCAN DIN A VIA/LIKE-MINDED COUNTRIES

61

demands of d e v e l o p i n g c o u n t r i e s in this field are quite broad

and nonspecific; this i n v i t e s deals where a community of

interest is p o s s i b l e .

The socioeconomic e f f e c t s on Sweden and

on the recipient c o u n t r y , and the question of whose i n t e r e s t s

are actually s e r v e d by s u c h deals are not a l w a y s c l e a r , nor

are they a l w a y s b a s e d on a domestic community of i n t e r e s t .

Critics

of

the

Swedish

practice

make

this

point

strongly.(12,13)

Transnational C o r p o r a t i o n s , Direct I n v e s t m e n t s ,

and T e c h n o l o g y T r a n s f e r

Sweden o c c u p i e s a p a r t i c u l a r l y prominent role in the a b o v e

areas.

Only a v e r y few transnational corporations ( T N C s )

from o t h e r Nordic c o u n t r i e s can actually match the g r e a t

number of S w e d i s h internationalized companies.

(See table

4.2.)

T h e p r e s e n t s h a r e , about 1 5 p e r c e n t , o f the Swedish

T N C s foreign sales in d e v e l o p i n g c o u n t r i e s will, no d o u b t ,

i n c r e a s e in the f u t u r e .

S w e d e n will p r o b a b l y be followed by

the o t h e r c o u n t r i e s in this r e s p e c t .

T h e r e is g e n e r a l s u p p o r t , both in government and among

labor unions in all Nordic c o u n t r i e s , for the need to control

transnational c o r p o r a t i o n s .

I T T in C h i l e , foreign investments

in S o u t h e r n A f r i c a , and similar h i g h l i g h t e d c a s e s of o b v i o u s

political-economic exploitation of T h i r d World economies h a v e

met with political reactions in S c a n d i n a v i a .

In s u c h c a s e s

g o v e r n m e n t s , p a r t i c u l a r l y i n S w e d e n , h a v e intervened t o

control "their" corporations and stop new i n v e s t m e n t s .

These

a r e , h o w e v e r , exceptional c a s e s .

S u p p o r t in principle at the

international level has not been matched by c o r r e s p o n d i n g

action at the national l e v e l .

L a b o r does not come forth with an a c t i v e policy in this

a r e a , but confines its activities to the European section of the

ICFTU and to Nordic cooperation.

In a statement issued by

the Nordic labor federations in 1977, Nordisk facklig samorganisation och en ny ekonomisk v a r l d s o r d n l n g , a more a c t i v e

line is called for in the I L O , t o g e t h e r with a major r e v i s i o n of

the OECD "Code of c o n d u c t " and a g u a r a n t e e of w o r k e r s '

r i g h t s to o r g a n i z e and negotiate with T N C s in d e v e l o p i n g

countries.

Norway s u p p o r t s the claim of d e v e l o p i n g countries to

assume national control o v e r their own r e s o u r c e s t h r o u g h

nationalization.

Norwegians h a v e , h o w e v e r , r e s e r v e d their

position on the question of legal p r o c e d u r e in the compensation

issue.

In Report n o . 94, it is e n v i s a g e d that increased

control o v e r T N C s "can be done p a r t l y by means of agreements

b e t w e e n the interested c o u n t r i e s , p a r t l y b y p r o v i d i n g the

international o r g a n i z a t i o n s with the n e c e s s a r y instruments to

s u p e r v i s e the operations of these c o r p o r a t i o n s . "

( p . 26)

1

1

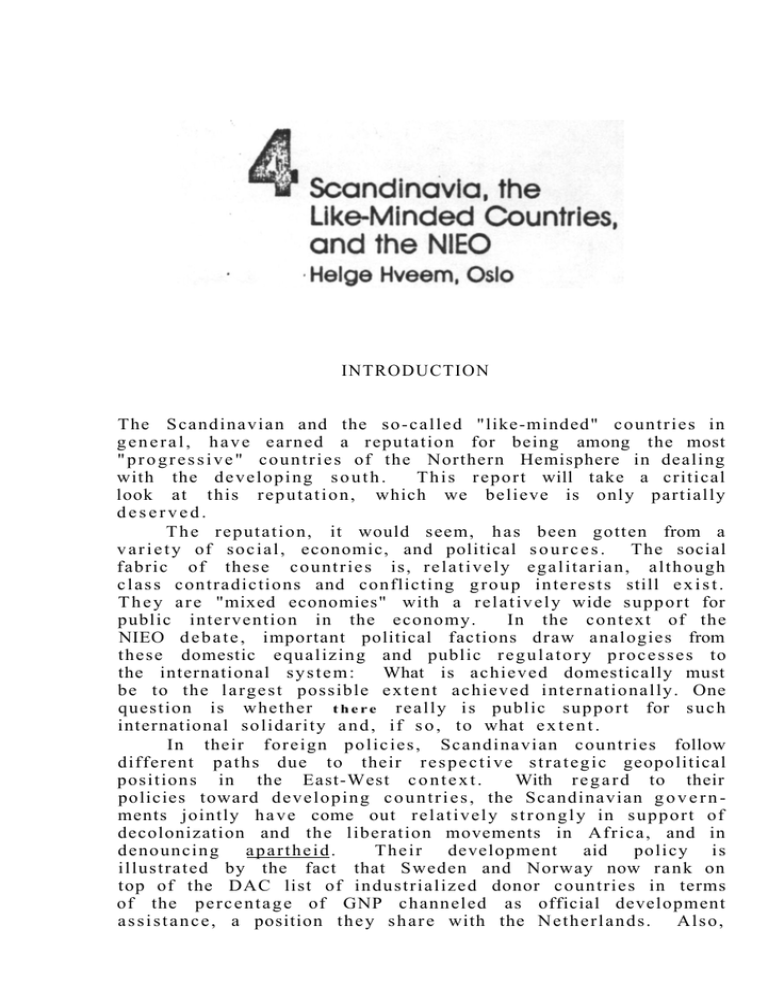

Foreign Content of Major Nordic Industrial Corporations. 1976

Table 4.2.

fore l,,, ••1••

Tolal

Con 0011... jo1

"ationanl, lndu.try

C:C-pany

laporta

Coy~rnme1'lt

dated

',.om

o_nc,.ah.ip

.al ••

tDuntry

(percent )

(Mm . I I

X.

home-

Saf•• 01 '°"'1"

ov.,. ..... emplo""e.nt

.rn H.t~.

to th ird

2 ar ti e •

pucent o! lotal

.. ptrc«nl

. f total

et!Ipl o'f"'"T'll

conaoJi dated ,al ••

~T",SIATISK

~OIlPACN I

YOI-VO

Denmark

rood

)2U I I'7)

S •• dcn

Woto r

•• tud ••

JUS

44

24

27

, .,.rt.

S1" ATSfORETAK

C R OUP

C'

S",Aa- SCAPiOIA

S • ..cSen

S.eden

Mi ni n,

100

Wotor

Z231

'2

2207

)2

n

14

n

Z9

,.

.thicl ••

l parte

N

ASEA

S .. "dtn

E).e.ctrical

un

£l.ECTROI-UX

S.eden

£ lKtrica1

17S6

)I

55

LN ER ICSO N T

S •• den

Electrical

1.7~

2l

.1

SKf AKTIE8 0l-ACET

S.edcn

Nonelectrical

0

aOl

14

n

M£STE

'inland

'etroa .. wn

100

1360

.7

li l A

li l A

7)

n

"

.0

"

IOO ltSK HYI7RO

NOT • • ,

Ch~ i caJ.

'44

1)

E:.KEII - SPIC£It VERKET

"OTWay

Ch .-nlcala

!IOO

S~

. ORUCAAltO

Nor •• .,

Chemic.b-

410

)4

n

20

400

71

10

U

SI.4

'aper

ASV

Norway

M.laI

,..linln,

1"01 an e..hau.tty. lbt o f compan.i ••.

•'Il . Not applicable .

100

Government officials c o n f i d e , h o w e v e r , that there is a g r o w i n g

disbelief in international regulation of T N C a c t i v i t i e s and that

the only e f f e c t i v e Way is to e q u i p individual d e v e l o p i n g

c o u n t r i e s with the means to b a r g a i n with T N C s t h e m s e l v e s .

V a g u e n e s s as to the c o n c r e t e action to be taken on the

international level is matched by u n c e r t a i n t y as to the action

to be taken on the national l e v e l .

As noted a b o v e , there are

v e r y few Norwegian T N C s , b u t those that e x i s t are increasing

their a c t i v i t i e s a b r o a d .

Most investments still go to developed

c o u n t r i e s , b u t investment in d e v e l o p i n g countries is i n c r e a s i n g , p a r t i c u l a r l y in the m a n u f a c t u r i n g , t r a d e , and shipping

sectors. (14,15)

T w o - f i f t h s of all individual investment in

d e v e l o p i n g c o u n t r i e s was made after 1968.

I n d u s t r y claims

that the main reason why t h e y a r e not y e t approaching a

substantial level of investment is the lack of i n c e n t i v e s by

government.

For its p a r t , government maintains that p r o p e r

i n c e n t i v e s are offered s u b j e c t to an assessment as to "whether

the investment schemes in question do in fact foster d e v e l opment."

( R e p o r t , p . 57)

Political c o n c e r n has been c o n c e n t r a t e d more on the

volume than on the form and the e f f e c t s of p r i v a t e , d i r e c t

i n v e s t m e n t s in developing c o u n t r i e s .

S u c h investments are

p r e s e n t l y s e p a r a t e d from ODA in N o r w a y ' s official p o l i c y ,

a l t h o u g h it is a c k n o w l e d g e d that to some e x t e n t they s u p plement each o t h e r .

New credit arrangements to promote

industrial development in developing countries h a v e been

c r e a t e d , but the government has not had an o p p o r t u n i t y to

apply formally the intended conditions and criteria for e x tending c r e d i t s (see Report n o . 94, p. 60 and p a s s i m ) .

The

question a r i s e s , h o w e v e r , w h e t h e r s u c h conditions would h a v e

been applied e v e n if t h e r e were means to i n t e r v e n e formally.

As an example, two "parastate" companies Invested in a h u g e

mining project in the Amazon despite political and public

questioning of its social, economic, ecological, and political

implications.

Government spokesmen h a v e stated p u b l i c l y that

they do not h a v e the political and legal means to i n t e r v e n e ,

e v e n if t h e y wanted t o , to i n s t r u c t these companies to act

o t h e r w i s e . (16)

S w e d e n ' s official policy follows from its mixed economy,

which Is actively adapting to the c h a n g i n g international

division of l a b o r .

T h e government and the labor movement

follow the social democratic tradition of p r o g r e s s i v e policies on

T N C s and investment in developing c o u n t r i e s . T h e criteria set

down by the p r e s e n t S w e d i s h government for s u p p o r t i n g

i n d u s t r y ' s investments in d e v e l o p i n g countries are s t r i c t e r ,

more c o n c i s e , and - more oriented m a s s - b a s e d development than

the Norwegian o n e s .

And the S w e d i s h labor movement has

been p a r t i c u l a r l y a c t i v e in proposing action to be taken in

T N C s and a r g u i n g for d i r e c t investments in developing c o u n t r i e s , internationally as well as domestically.

S u c h action

i n c l u d e s a s s i s t a n c e to w o r k e r s In affiliates of S w e d i s h T N C s

a b r o a d , and e v e n s y m p a t h y s t r i k e s and e m b a r g o s , and c o ordination of policy to avoid b e i n g s u b j e c t e d to s p l i t - a n d - r u l e

t a c t i c s by T N C s , e t c . ( 1 7 ) T h e demand for a social c l a u s e to

be included in the G A T T r u l e s testifies to the international

c o n c e r n of S w e d i s h social d e m o c r a c y .

On the o t h e r h a n d , c r i t i c s of S w e d e n ' s p o s t w a r policy

h a v e pointed out that it was u n d e r social democracy that

S w e d i s h i n d u s t r y was able to internationalize at a h i g h s p e e d

and on a broad s c o p e . S w e d i s h investments abroad quintupled

o v e r t h e last IS y e a r s and r e p r e s e n t four times the value of

foreign i n v e s t m e n t s in S w e d e n .

T h i s trend seems to be

continuing and may c a u s e economic s t a g n a t i o n , i n c r e a s e d

unemployment and i n c r e a s e d concentration in S w e d i s h s o c i e t y . (18) In some c a s e s S w e d i s h capital p r e f e r s to go a b r o a d

if the w o r k e r s p e r s i s t in demanding industrial d e m o c r a c y , a

partial control o v e r the c o m p a n y ' s s u r p l u s ( L o n t a g a r f o n d ) , and

that new f a c t o r i e s be located in p e r i p h e r a l r e g i o n s of S w e d e n .

In the s h o r t r u n S w e d i s h T N C s are e x p e c t e d to affect p o s i t i v e l y domestic employment b e c a u s e they i n c r e a s e demand for

e x p o r t s from S w e d i s h factories to the new affiliates a b r o a d .

B u t in the medium and long r u n , t h e y will demand more and

more i n p u t , raw materials and o t h e r g o o d s froin a b r o a d , t h u s

h a v i n g a n e g a t i v e effect on S w e d i s h economy and employment.

S c i e n c e and T e c h n o l o g y Policy

S c i e n c e and t e c h n o l o g y in the c o n t e x t of development problems

in the T h i r d World is a r e l a t i v e l y new field for Scandinavian

countries.

In terms of t r a n s f e r s of k n o w l e d g e to d e v e l o p i n g

c o u n t r i e s , Sweden again o c c u p i e s a special position by v i r t u e

of the i n t e r e s t of Swedish capital in internationalized p r o duction.

But e v e n in terms of the public s e c t o r , S w e d e n is in

t h e forefront compared with its Nordic n e i g h b o r s .

Generally,

the role of s c i e n c e and t e c h n o l o g y for development so far has

been marginal in the debate on development aid s t r a t e g i e s .

E x p o r t s and p r i v a t e investments t r a n s f e r r i n g t e c h n o l o g y h a v e

also b e e n by a n d l a r g e outside the control of g o v e r n m e n t .

T h e g o v e r n m e n t , h o w e v e r , h a s not tried t o e x e r c i s e s u c h

control.

S w e d i s h preeminence in this field can be explained by

the c o u n t r y ' s position in the international division of l a b o r .

While the o t h e r Nordic c o u n t r i e s are adapting more p a s s i v e l y to

their international e n v i r o n m e n t , Sweden p u r s u e s a more a c t i v e

s t r a t e g y . (19)

A c c o r d i n g to K a t z e n s t e i n , Denmark and Norway

(and p r e s u m a b l y Finland, which he d o e s not d i s c u s s ) follow a

policy of d e f e n s i v e adaptation.

O t h e r small c o u n t r i e s with

some

particular

comparative

advantage,

like

Switzerland

(pharmaceutical i n d u s t r y and b a n k i n g ) and the Netherlands

(some b i g T N C s ) follow a policy of o i l e n s l v e adaptation.

Sweden o c c u p i e s an i n - b e t w e e n position in the international

division of l a b o r , but in the crucial field of science and

t e c h n o l o g y it is quite close to the S w i s s and D u t c h .

While

Denmark and Norway s p e n t 1 p e r c e n t of their GNP on r e s e a r c h

and development in the b e g i n n i n g of the 1970s. S w e d e n s p e n t

1.7 p e r c e n t and the Netherlands 2.0 p e r c e n t - a p e r c e n t a g e

comparable with that of the f i v e big capitalist c o u n t r i e s in the

w o r l d . (20)

All the Nordic c o u n t r i e s are heavily d e p e n d e n t on imports

of capital g o o d s and technology In other forms, Sweden again

being a partial e x c e p t i o n .

T h i s d e p e n d e n c e , which c o r r e s p o n d s in some r e s p e c t s to that which d e v e l o p i n g countries

face, is s t r o n g l y felt in many k e y industrial s e c t o r s .

As an

example, Norway is building its oil economy with the help of

massive and costly imports of foreign t e c h n o l o g y .

T h i s had a

profound impact on Norwegian balance of payments o v e r the

last few y e a r s , s i n c e e x p o r t s h a v e stagnated and e a r n i n g s

from the s h i p p i n g s e c t o r h a v e d e c r e a s e d .

N o r w a y ' s official policy on s c i e n c e and technology for

development is still in the m a k i n g .

T h e national p a p e r

p r e s e n t e d to the UN C o n f e r e n c e on S c i e n c e and T e c h n o l o g y for

Development ( U N C S T D ) s t r e s s e d the need for d e v e l o p i n g

c o u n t r i e s to become more autonomous in s c i e n c e and technology

and that a p r i o r i t y for international cooperation, including

t r a n s f e r of t e c h n o l o g y , is to s t r e n g t h e n their c a p a c i t y in that

respect.

It also called for more emphasis on the development

and utilization of e n d o g e n o u s and available technology in

d e v e l o p i n g c o u n t r i e s and s u g g e s t e d a s s i s t a n c e to achieve t h i s .

As the p a p e r p u t s it, " T h e aim should be to d e v e l o p science

and t e c h n o l o g y as d i r e c t l y as possible where people need them,

b e a r i n g in mind t h a t the i n s i g h t and the technology already

p r e s e n t r e p r e s e n t e d a rationality that should be maximally

e x p l o i t e d and improved u p o n . "

Officially,

NORAD

monitors

technology in bilateral

development aid p r o j e c t s .

H o w e v e r , this monitoring seems not

to h a v e b e e n v e r y e f f e c t i v e so f a r .

One important form of

t e c h n o l o g y t r a n s f e r t h r o u g h Norwegian aid programs is c o n s u l t a n c y s e r v i c e s , where a small number of firms dominate the

m a r k e t . One of them, N O R C O N S U L T , h a s done extremely well

commercially e v e n by international s t a n d a r d s . (21) T h e r e is no

public control o v e r technology in p r i v a t e e x p o r t s and i n vestments.

Until 1977 NORAD had a formal responsibility to

evaluate e x p o r t s , before state s u p p o r t is g r a n t e d in the form

of e x p o r t c r e d i t s on i n t e r e s t s .

T h i s responsibility was withdrawn in 1 9 7 7 , and the decision on s u b s i d i e s , inter alia with

r e g a r d to shipbuilding c o n t r a c t s has been v e s t e d solely with

the Ministry of T r a d e .

S w e d e n ' s c o n t r i b u t i o n s in this field d e r i v e mostly from

unplanned benefits from r e s e a r c h and development activities

due to the internationalization of S w e d i s h i n d u s t r y and planned

a c t i v i t i e s within the state s e c t o r .

I n d u s t r y ' s r e s e a r c h and

development policy has been oriented toward i t s own n e e d s ,

and a global profit s t r a t e g y .

S i n c e the late 1960s, the public

s e c t o r c o n c e r n e d with development aid has b e e n e n g a g e d in

comparatively l a r g e - s c a l e r e s e a r c h p r o g r a m s related t o d e veloping c o u n t r i e s .

S w e d e n ' s financial contribution to r e s e a r c h and d e velopment problems g r e w from 5 to 50 million S w e d i s h k r o n e r

from 1967 to 1973 and continued i t s expotential g r o w t h to reach

100 million in 1978 and 1 9 7 9 . About t w o - t h i r d s is channeled to

international o r g a n i z a t i o n s , with a concentration on family

p l a n n i n g , employment, and n u t r i t i o n .

About 12 p e r c e n t of

total

appropriations

were

channeled d i r e c t l y to r e s e a r c h

institutions in d e v e l o p i n g c o u n t r i e s ( 1 9 7 2 - 1 9 7 3 ) .

In o r d e r to

o r g a n i z e and coordinate these a c t i v i t i e s ,

the g o v e r n m e n t

e s t a b l i s h e d in 1975 a s e p a r a t e institution, the S w e d i s h A g e n c y

for R e s e a r c h Cooperation with Developing C o u n t r i e s ( S A R E C ) .

T h e institution, which is l a r g e l y independent of S w e d i s h

International Development A g e n c y

(SIDA),

h a s the twin

function of s u p p o r t i n g d e v e l o p i n g c o u n t r i e s in their effort to

build their own c a p a c i t y in r e s e a r c h and accumulate and

s p r e a d knowledge about development questions in S w e d e n .

In a s u r v e y of technology t r a n s f e r s by S w e d i s h i n d u s t r y ,

it was found that only in a few c a s e s S w e d i s h firms had

developed

technology

products

and

processes

especially

adapted to the n e e d s of d e v e l o p i n g c o u n t r i e s .

Examples

included

transportation

equipment

and

wood-treating

machinery.

Profitability considerations are still dominant in the

firms' t h i n k i n g about their a c t i v i t i e s in d e v e l o p i n g c o u n t r i e s ,

but a few firms showed c o n c e r n about their social implications.

( U N C S T D National R e p o r t , p . 4 3 f f . ) T h e g o v e r n m e n t seems

to h a v e no p a r t i c u l a r intention to i n t e r f e r e with the a c t i v i t i e s

of S w e d i s h p r i v a t e firms in this field, b e y o n d the g e n e r a l

p r i n c i p l e s it has s e t down for e x t e n d i n g loans t h r o u g h the

newly e s t a b l i s h e d industrialization f u n d .

T h e r e will be more

concern

for selling a p p r o p r i a t e t e c h n o l o g y to d e v e l o p i n g

countries,

a c c o r d i n g to government t h i n k i n g , when these

c o u n t r i e s become more important markets for S w e d i s h firms.

Raw Materials

All the Nordic c o u n t r i e s h a v e p u b l i c l y s u p p o r t e d , in v a r y i n g

d e g r e e s , the I n t e g r a t e d Program for Commodities (IPC) and

the establishment of a Common Fund ( C F ) from the o u t s e t .

Norway h a s been the most e x p r e s s i v e l y p o s i t i v e , Finland and

Denmark the least s o . T h i s difference p r o b a b l y h a s a political

background.

A l t h o u g h Finland's r e l a t i v e l o w - k e y e d policy o n

the CF could be e x p l a i n e d by her d e p e n d e n c e on the im-

portation of raw materials, national economic i n t e r e s t s h a v e

p r o b a b l y not p l a y e d a major r o l e .

It may, h o w e v e r , be said

that h i g h import d e p e n d e n c e on raw materials and their

r e l a t i v e l y small size make the Nordic countries r e c e p t i v e to

NIEO demands.

All four Nordic c o u n t r i e s are dependent on

imports of raw materials o t h e r than food, as shown in table

4,3.

Whereas the d e p e n d e n c e as compared with the position of

the l a r g e OECD c o u n t r i e s is clearly c o n s i d e r a b l e , the difference b e t w e e n the Nordic c o u n t r i e s is i n s i g n i f i c a n t .

Hence,

import d e p e n d e n c e is only p a r t of the explanation for the

v a r y i n g Nordic s u p p o r t of the IPC and the Norwegian p r o g r e s s i v e n e s s on the i s s u e .

It should be noted, h o w e v e r , that

Sweden is a major e x p o r t e r of iron and steel p r o d u c t s and an

important p r o d u c e r of s u g a r and that Norway p r o d u c e s and

e x p o r t s sizable quantities of c o p p e r and iron p r o d u c t s .

State

s u b s i d i e s , to s a v e employment in these s e c t o r s , h a v e been

considerable.

In 1977 the Norwegian government s p e n t more

on s u b s i d i e s to the c o p p e r i n d u s t r y , which is some 60 p e r c e n t

controlled by the s t a t e , than it i n v e s t e d in the C F .

T a b l e 4 . 3 . Import of Selected Raw Materials

( E x c l u d i n g A g r i c u l t u r a l Goods)

as P e r c e n t a g e of G r o s s Factor Income 1972,

N o r w a y ' s position on the IPC and the CF has been consistently

in s u p p o r t of d e v e l o p i n g c o u n t r i e s ' demands, while at the same

time t r y i n g to balance this s u p p o r t with the need to s t a y in

line with the OECD g r o u p .

T h i s balancing act led to U n d e r S e c r e t a r y of State S t o l t e n b e r g ' s election as chairman of the

n o r t h - s o u t h committee for the CF d i s c u s s i o n s .

Norway was the

first among the industrialized c o u n t r i e s to p l e d g e a c o n tribution to the C F .

T h e $25 million offered at UNCTAD IV

was far in a c c e s s of the contribution e x p e c t e d of Norway