Introduction

advertisement

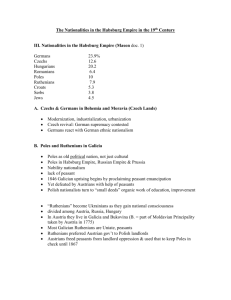

Introduction There has been a significant amount of new literature on nations and nationalism in recent years. (...) Polemically, one might say that at the moment we have an overproduction of theories and a stagnation of comparative research on the topic. Miroslav Hroch 1 The empirical focus of this thesis is the national relations between Czechs and Slovaks during the First Czechoslovak Republic (1918–38). Czechoslovakia was founded in the heyday of the principle of national self-determination. Although one of the nationally most heterogeneous successor-states of the Habsburg empire,2 it was from the outset presented as the nation-state of the "Czechoslovak nation with two tribes." This notion, for which I have adopted the term Czechoslovakism,3 remained the official doctrine throughout the First Republic, and was abandoned only reluctantly after the Munich settlement of 1938. The Czechs and the Slovaks had lived in separate parts of Austria-Hungary before 1918 – the Czechs in Austria, the Slovaks in Hungary. While the Czechs had lost their independence gradually from 1526, the Slovaks had never had a state of their own. Both national revivals started in the late 18th century, but neither the Czechs nor the Slovaks filed demands that went beyond autonomy in a federalized Austria-Hungary until 1915. During the First World War, an exile movement with Tomáš G. Masaryk, Edvard Beneš and Milan R. Štefánik at the helm advocated the establishment of a joint Czecho-Slovak state, and managed to convince the Allies that the Czechs and Slovaks were one nation and deserved their own state. This was accepted by Czech and Slovak elites once they realized that Austria-Hungary was doomed. At the inception of the First Republic, elite relations between the Czechs and Slovaks were fairly cordial. Differences soon arose, however, and for most of the 20 years the First Republic lasted, Slovak autonomists were pitted against Czechoslovak centralists. As these labels suggest, the identity struggle between proponents and opponents of Czechoslovakism was closely linked to a dispute over the political-administrative organization and distribution of power. The federalization of Czechoslovakia following the Munich settlement thus represented a double victory for Slovak autonomists, marking the end of Czechoslovakism. 1 Miroslav Hroch: From national movement to the fully-formed nation, in: New Left review 198/April 1993:3-4. 2 This was also an effect of the fact that historical and strategic considerations were as important as national principles in determining the state borders. According to the Czechoslovak census of 1921, there were 13.4 million Czechoslovak citizens. Of these, Czechs and Slovaks together comprised 65.5 percent, Germans 23.4 percent, Magyars 5.6 percent, Ruthenians 3.5 percent, Jews 1.4 percent, Poles 0.6 percent and "others" 0.2 percent. The largest among "others" were Rumanians (13,974 persons), Gypsies (8,446) and Yugoslavs (2,108). See Sčítání lidu v republice československé ze dne 15. února 1921, Díl I, (1924:60, 66). 3 See e.g. Josef Tomeš: Slovník k politickým dějinám Československa 1918–1992 (1994:17). 2 Linguistically and culturally, the Czechs and Slovaks were close enough that the Czechoslovak nation project conceivably might work. The primary objective of this thesis has been to explain why it did not, and why the level of conflict rose instead. The problem formulation is thus dual: (1) What was the basis for the increased national conflict between Czechs and Slovaks during the First Republic? (2) Why did the Czechoslovak nation project fail? These questions are partly overlapping. On the one hand, the chances that an overarching nation project will succeed may be expected to be inversely related to the conflict level. On the other hand, an attempt to advance an overarching nation project like this in the face of strong opposition from one of the target groups may be expected to exacerbate national conflict. In order to answer the first question, I have analyzed the national complaints and demands that were voiced in debates and interpellations in the Parliament. This approach was based on the assumption that in a democracy, the most important national conflicts will be articulated politically. An interesting question is whether government policies contributed directly or indirectly to the increased national conflict between Czechs and Slovaks. If it did, we need to ask what the government could have done differently, and under what restraints it operated. In order to answer the second question, I have in addition analyzed Czechoslovakism qua ideology – with special focus on its actual dispersal and the content of the ideology. First, if Czechoslovakism was not advocated consistently, this could be part of the reason why it failed. I have thus tried to establish to what extent it was advocated. Second, there may be elements in the ideology that worked against it. In order to identify such controversial points, it has been necessary to go into the scholarly debate about Czechoslovakism in some detail. A secondary objective has been to shed light on what motivated the leading politicians on either side, with special focus on why consecutive Czechoslovak governments kept insisting on a unitary Czechoslovak nation and state, long after it was clear that this had failed. Here it has been necessary to go into the political debate about Czechoslovakism. In terms of theory, this thesis draws on two partly overlapping theory traditions: Theories of nations and nationalism, and typologies of national conflict regulation. Theories of nations and nationalism tend be oriented towards explaining causally why and how nations and nationalism originated in the past, while scholars who focus on national conflict regulation tend to be oriented more towards policy implications in contemporary multi-national states. My ambition has not been to add another theory, but rather to combine existing theories in order to shed light on an empirical material. The main theoretical contribution is the development of a framework to aid the analysis of national conflict in multi-national states, through an elaboration of the nationality policy concept. A nationality policy is defined as a multidimensional concept, involving consciously designed policies at a symbolic level and a practical level within the political, the cultural and the economic domains. By relating common government policies to common demands made on behalf of national groups, this nationality policy framework yields a theoretical grid within which national demands and policies can be said to vary. At the same time, it provides a point of departure for developing explanations to why a certain nationality policy succeeded or failed. 3 The result of the analysis is admittedly a rather bulky narrative – some might say too bulky. First, the topic is in itself extensive, and I could easily have doubled the length of this presentation. Second, it has been my aim to give as complete and cohesive a picture as possible, both of the dispute about national identity between Czechoslovakists and Slovak autonomists and of the struggle about cultural rights, political power and economic redistribution. I have sought to document what the national conflicts were all about, how they were related and what the government did in order to alleviate them. Third, I have wanted to give a "thick" description, in terms of providing the necessary historical context, and in terms of conveying some of the flavor and texture of the actual disputes. Although the main objective of this thesis is empirical, there are also some interesting theoretical implications. First, the thesis goes right into one of the most crucial disputes in the theoretical debate about nations and nationalism: Whether nations can be purposefully constructed. Official Czechoslovakism is a clear example of an attempt at forging a new overarching national identity. An analysis of why it failed may yield new insight into the conditions for success and failure in the attempted "construction" of national identity. Second, this thesis seeks to contribute to the body of knowledge about what causes national conflict, through the analysis of the national demands made on behalf of the Slovak nation. An interesting point is to what extent such demands or complaints were directly associated with what Hroch calls nationally relevant conflicts, which occur when national divides coincide with some other conflict of interest.4 This is also a question of to what extent national sentiment is susceptible to manipulation. Delimitation It goes without saying that all aspects of the national relations between Czechs and Slovaks during the First Republic could not be included, even in this bulky narrative. I have chosen to exclude from the analysis national minorities as well as foreign policy considerations and international events. My focus will be on elite relations between Czechs and Slovaks. There are partly practical, partly theoretical reasons for this. The focus on national relations between Czechs and Slovaks and the problem formulation on the previous page confines the study theoretically. A practical consideration was that the available time and financial resources were limited. In addition, I encountered problems with the sources. My main reason for excluding the national minorities is that they were never meant to be a part of the Czechoslovak nation project; indeed, in the case of the Germans and Magyars, they were even presented as the enemies of the "Czechoslovak" state-nation. German and Magyar national demands and complaints will thus be mentioned only to the extent that they are relevant to Czecho-Slovak relations. Likewise, foreign policy considerations and international events are generally left out, unless they have a direct bearing on these relations. 4 Miroslav Hroch: Social preconditions of national revival in Europe (1985:185). 4 This also means that although the Munich settlement of September 30th 1938 was obviously an important precondition for the federalization of Czechoslovakia, the event in itself and the background for it are of minor interest in our context.5 More importantly, the study is confined to national relations at the elite level. The elite in question was mainly a political elite (Cabinet members and members of Parliament), but also to some degree an intellectual elite. With respect to the Parliament, I have put main emphasis on the Chamber of Deputies, since this is where the real power lay. In the 20 years of the First Republic, there is not one example of ministers being recruited among the senators, according to Dušan Uhlíř.6 The difference in power and importance is also reflected in the sheer volume of the stenographic notes of the two chambers. My original plan was to find out to what extent the Czechoslovak nation project was a success also at the mass level, and conversely, whether the level of conflict increased among ordinary people. Jiří Musil suggests that the degree of integration at mass level can be investigated by looking at the number of intermarriages, migration of Czechs to Slovakia and vice versa, the number of Czech and Slovak students studying outside their home region, tourism, the volume of cultural contacts and the mutual knowledge of language, culture and history.7 Of Musil's suggestions, the number of intermarriages would probably be the most reliable measure. Several scholars have argued that intermarriage is a sign of social nearness – cf. Mitchell's scale of social nearness or social distance, where willingness to allow someone into the family though marriage signals maximum social nearness. Large-scale intermarriage across the former ethnic boundaries is also the ultimate proof of successful assimilation in McGarry/O'Leary's scheme.8 If the number of intermarriages between Czechs and Slovaks were higher than e.g. between Czechs and Germans or Slovaks and Magyars, and increasing, this would at least suggest that integration was taking place. Here a problem arises. Most statistical data from the inter-war period, including statistics of Czecho-Slovak intermarriages, are obscured by the fact that due to Official Czechoslovakism, Czechs and Slovaks were habitually presented as one nation in statistics pertaining to nationality. This also means that the progress of Czechoslovakism in terms of how many declared "Czechoslovak" nationality in the population censuses cannot be measured. 5 Through the Munich settlement Czechoslovakia lost the German inhabited border areas to Nazi Germany, and parts of Těšín to Poland. In the Vienna award of November 1938, Czechoslovakia lost the Magyar-inhabited southern rim of Slovakia to Hungary. See e.g. map (and text) in Paul Robert Magocsi: Historical atlas of East Central Europe (1993:132). On Czechoslovak foreign policies, see e.g. Antonín Klimek and Eduard Kubů: Československá zahraniční politika 1918–1938 (1995); Igor Lukes: Czechoslovakia between Stalin and Hitler. The diplomacy of Edvard Beneš in the 1930s (1996). 6 Dušan Uhlíř: Republikánská strana venkovského a malorolnického lidu 1918–1938 (1988:142–43). See also Oskar Krejčí: Kniha o volbách (1994:134); Joseph Rothschild: East Central Europe between the two world wars (1992:93). 7 See Jiří Musil: The end of Czechoslovakia (1995:89). 8 Mitchell referred in Thomas Hylland Eriksen: Ethnicity and nationalism, (1993:25); John McGarry/Brendan O'Leary: The politics of ethnic conflict regulation, (1993:17). 5 As for Musil's other suggestions, an increasing exchange of students, tourists and workers would not necessarily mean that a Czechoslovak nation was coming into being. Given unequal work and study opportunities between regions, it could rather be expected that people would have to move outside their own region to work or study. Internal migration data are available only for the population census years 1921 and 1930, and employment data for Czechs working in Slovakia and Slovaks in the Czech lands were hard to come by. The only such data I have found are from two articles in the statistical journal Československý Statistický Obzor in the 1930s.9 As for cultural contacts and knowledge of language, culture and history, statistics are entirely lacking. Here the situation can be assessed only indirectly. Insufficient data are thus the most important reason for my decision not to focus on mass relations. Outline of the theoretical approach According to Craig Calhoun, the term "theory" is used in three different ways by social scientists; theory as an orderly system of tested propositions; theory as logically integrated causal explanation; and theory as theoretical perspective – approaches to solving problems and developing explanations rather than the solutions and explanations themselves.10 My theoretical approach is theory in the third sense of the word, meaning that it is as much a way "of thinking about the empirical world" as a way of explaining what is going on. In this perspective, theories are seen as instruments of understanding rather than reproductions or recreations of reality. Theories are not "true" or "false", but more useful or less useful; good theories help us to structure our knowledge about the world in meaningful ways. The national conflict level in multi-national states is in my view the outcome of four factors: The existence of national "we-groups"; the actual differences between them in political power, social position and cultural opportunities; how these differences are perceived and presented in terms of national demands on behalf of the various national groups; and how these demands are met by the government in terms of a nationality policy. The former two are seen as preconditions of national conflict, while the dynamics between the two latter are seen as crucial for the outcome. This is also where the main emphasis of this study lies. National demands are based on the perception of a problem and the call for solutions to the problem. Demands are made on behalf of the nation by a group of people claiming to represent it, and are directed against the government. An asymmetric power relation is thus acknowledged. National demands vary in terms of scope and content. They are principally of two different kinds: symbolic demands (mostly) related to recognition of national existence, and practical demands related to the actual situation of the members of the nation. The difference is not always clear-cut. Within the group of practical demands, there are cultural, political and economical demands. 9 10 Antonín Boháč: Češi na Slovensku in: Statistický obzor (1935:183–90), Pavol Horváth: Slováci v Českých zemiach, in the same journal (1938:223–26). I will return to these figures in a later chapter. Craig Calhoun: Critical social theory, (1996:5–6). 6 Governments relate to these demands through a nationality policy, by accommodating or rejecting them. In addition, governments often have an agenda of their own, aims meant to be fulfilled by the nationality policy – as in this case, arguably, the creation of a new national identity. Nationality policies are then more or less efficient means to an end, whether the aim is to pacify a national movement or to form a new nation. This approach to the study of national conflict rests on certain basic assumptions. First, there is an assumption about the nature of national identity. Identity requires (1) that the members of the group have something in common, that there are important others who do not share this feature, who can provide a contrast to the we-group, and (2) that the members of the group recognize each other as belonging to the group, and feel themselves to be a group. This also means that national identity has more to do with feelings, a sense of community with those who are in a deep sense "like us", than with any rational selection of means to an end. National identity thus has a clearly expressive side, and this is also reflected in the national demands. Second, it is assumed that different national identity is not in itself enough to cause conflict. If a state contains more than one national group, this will not automatically lead to national conflict. It is a necessary, but not a sufficient, precondition for conflict. Assuming the opposite would mean that all multi-national states are doomed to disintegrate sooner or later, and that only nation-states are stable. A third, related, assumption is that actual differences in power and access to goods and values are in fact important in order to understand why national conflict occur, which implies a certain materialist bias. However, it is not assumed that ideas or identities are unimportant, or that national conflict can be reduced to differences in material interests, the way some Marxists seem to think. What is assumed is that differences in national identity must to a certain extent correspond to differences in power or access to goods and values in order to cause conflict. A fourth assumption is that inequality between national groups is deemed illegitimate by the members of the less-favored national group, which means that inequalities become objects of complaints directed against the government of the multi-national state. This also implies that the perception of inequality is just as important as the realities. A corollary is that inequalities deemed legitimate by those concerned do not generate conflicts. In feudal society, inequality was seen as instituted by God, and thus tolerable. In a society of (presumably) equal citizens, this is no longer the case. The notion of equality has become an inherent part of the nation idea – in terms of a world of equal nations as well as a community of equal co-nationals. A fifth assumption is that people who get what they want (national demands are accommodated), become satisfied, which means that national demands that are met disappear from the agenda. Conversely, it is assumed that the failure to meet demands will cause dissatisfaction, which tend to raise the conflict level. This is not entirely unproblematic – national demands tend to escalate, from modest, cultural claims to far-reaching political claims, and if a government gives in to some national demands, new ones may follow. Conversely, a repressive strategy may yield lesser demands, to the extent that some options will be deemed unrealistic or impossible. I will return to some of these problems in Chapter Four. 7 Structure of the thesis The theoretical framework of the study (briefly outlined above) is presented in Part One. First some problems associated with the use of method and sources are addressed. Second, some of the central concepts, chiefly nation and nationalism are clarified. This is followed by an overview of the theoretical debate on these matters. Finally, I propose a framework for the study of national conflict in multi-national states by relating common national demands to common nationality policies. Here I distinguish between a symbolic and a practical level, and I range nationality policies from accommodating via neutral to repressive strategies within a cultural, an economic and a political dimension. Part Two concentrates on the historical context. First an outline of Czech and Slovak history is given, with special emphasis on the foundation for national identity. Then follows an overview of the Czech and Slovak nation-forming process, and finally the changes in Czech and Slovak identity in the course of the national "awakening" are discussed. This historical part provides the necessary historical setting for the analysis of Czecho-Slovak relations in general during the First Republic. In addition, an outline of Czech and Slovak history, and especially the national revival, is necessary as a backdrop to the analysis of the struggle for national identity, since the interpretation of history was such a central part of it. Part Three is the main part of this thesis. It is subdivided in six chapters. Chapter Eight is a presentation of the political and/or intellectual elite that formulated the national demands and the nationality policies. Chapter Nine and Ten focus on the struggle over national identity. Chapter Nine concentrates on documenting Official Czechoslovakism, with special emphasis on the contents and dispersal, while Chapter Ten is about the scholarly and political debate. Part of the answer to why Czechoslovakism failed will be suggested already here. The three next chapters are centered on the dynamics between national demands (mostly on behalf of the Slovaks) and the nationality policies of the Czechoslovak government on a more practical level – concerning cultural rights, economic redistribution and political power. Chapters Eleven and Twelve address nationally relevant conflicts within the cultural and economic dimensions that may have acted to exacerbate national conflict between Czechs and Slovaks, and what the government did to alleviate them. One point of departure for these chapters is the demands and complaints filed on behalf of the Slovak nation (and to a much lesser extent the Czech) in the Parliament. Chapter Thirteen concerns the political dimension, focusing on the admittedly very unequal tug-of-war between Czechoslovak centralists and Slovak autonomists over the political-administrative organization and political-territorial power distribution of the state. The main emphasis is on the autonomy proposals and the arguments in favor of and against Slovak autonomy. Combined with Chapter Ten, this Chapter also sheds light on the motives of central politicians. Finally, in the Conclusion, I will summarize the results, return to the overarching questions that were presented on page 2, and discuss some theoretical implications of the findings of this thesis.