Document 11448404

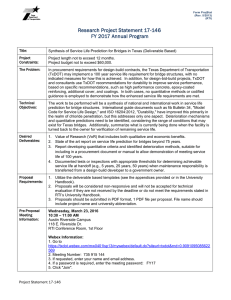

advertisement