THE LOGICAL BASIS OF EXCLAMATIVES

advertisement

JSM05

ENS, Paris, 17-18 mars 2005

THE LOGICAL BASIS OF EXCLAMATIVES

Kjell Johan Sæbø

Université d’Oslo

•

Long-term task: Learn more about the relation between sentence types and Speech Acts

–

Because: Searle used an indiscriminate notion of Propositional Content; but:

Sentences used as utterances can have various logical types, and not every type

is appropriate for every act

(Ex.: Questions (erotetics) are normally done with interrogative sentences,

of type <<s,t>,t> (Karttunen-style) or <s,<s,t>> (Groenendijk-Stokhof-style);

with some interesting exceptions (Gunlogson 2003))

+

Recent renewed interest in these issues, inspired by Krifka (2001), Zaefferer (2001)

•

Short-term task:

Answer the question "What about sentences of type <s,t>, denoting propositions, as

opposed to sentences of type t, normally used for assertions?"

*

Claim

*

Such utterances are normally used as Expressives:

Exclamatives or Optatives

In fact, I will argue for the following logical type – speech act correspondence chart

(the dotted diagonals reflect the option of type lifting):

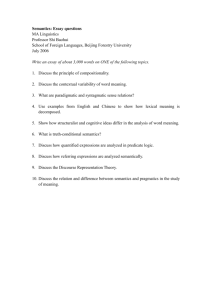

Type

Act

t

assertion

<s,t>

expression

<s,<s,t>>

question

And the following basic act definitions, inter alia:

• Assertion(e)(p)(a)(s) only if e is an utterance of p to a by s designed to add

to CommonGround(a)(s)

• Expression(e)(p)(a)(s) only if e is an utterance of p to a by s designed to

communicate to a a modal attitude of s to p

• Question(e)(p)(a)(s) only if e is an utterance of p to a by s designed to

procure an utterance by a adding p(v) to CommonGround(a)(s)

λv.p

*

Hypothesis

*

Utterances of necessarily or ostensively true <s,t> sentences are used as Exclamatives –

and predictably so:

Whenever a true proposition denoting sentence is uttered, the natural way to make sense of it

is to supplement an exclamative speech act function; the default modal attitude towards a fact

at the speech act origo (I, now), typically astonishment, but occasionally emotionally flavoured

as annoyance, joy, or marvel (similarly Rexach 1996 and Zaefferer 2001). Particularly – contra

e.g. Zanuttini and Portner (2003) – there is no (need for an) exclamative syntax or semantics!

2

Varieties of type <s,t> sentence utterances – mono- and crosslinguistically

2.1

"That" clauses (as ostensively true <s,t> sentences)

English barely makes use of "that" clauses as independent utterances.

French has "que" – but with the indicative, this is a wh- or relative "que" (see section 2.2.1);

and with the (here covert) subjunctive, "que" clauses encode counterfactual wish (optative):

(1)

Que la foudre tombe sur une pareille maison!

Wenn doch der Blitz in so ein Haus einschlagen würde!

I wish lightning would strike that house!

(attested translation)

(attested translation)

(attested translation)

Delimit also from cases of ellipsis (contextual binding), as in (2) (attested translations):

(2)

"I hear you know a great deal about Stine and me. That we live like a married couple!"

"J’me suis laissé dire que Niels en sait un bout sur la vie qu’on mène, Stine et moi.

Qu’on est comme qui dirait mari et femme!"

German (and Scandinavian), however, fairly freely uses "dass" clauses to express facts:

(3)

Dass die U-Bahn noch fährt!

‘Well, I never, the tube is still running!’

(Schwabe 2004)

(4)

Dass du dich daran noch erinnerst...!

‘It’s amazing that you still remember!’

(attested)

The "raw" theory of "that" ("que", "dass", "at") is that it intensionalizes a sentence:

(D1)

that =

λϕ<t> λw ϕ[v/w]

This is in Ty2, a language with possible-world variables w and an actual-world variable v.

The "refined" theory is that it presupposes a proposition (an intensionalized sentence):1

(D2)

that =

λϕ<s,t> ϕ

Anyway, the result is a proposition. Now the assertion operator is usually taken to operate on

propositions (Krifka 2001: 21); but "that" clauses are inappropriate as assertion utterances. !?

Proposal: The assertion function is a function from i.a. type t, truth value denoting sentences.

1

Cf. Fabricius-Hansen and Sæbø 2004 and Sæbø 2001; assuming a composition principle "Intensional Functional

Application" yielding the same result as (D1): ƒ<<s,t>,a>(g<t>) = ƒ(λw g[v/w])

2.2

Indirect Questions (as necessarily true <s,t> sentences)

Standard case:

(5)

How cold it is!

Wie kalt es ist!

Combien il fait froid!

(rare; cf. below)

Derivation of "how cold it is", according to Groenendijk and Stokhof (1997 and earlier)

equivalent to "that it is (at least) as cold as it is" (simplified):

(5D)

λw t°w ≤ t°v

how cold

λw t°w ≤ @(t°w)

C

λϕ<s,t> ϕ

t°v ≤ @(t°v)

it is

Ø

t°v ≤ @(t°v)

how

λα α ≥ @(α)

cold

t°v

More complex cases will be more difficult, of course. But this illustrates the general plot:

• The wh- word is assumed to introduce an equation between two values where one is bound

to the actual world through the actuality operator @ – for any w, @ζ = ζ[w/v]

• The raising to Spec,CP is assumed to trigger intensionalization, by making C visible;

a visible C, like a subjunction, introduces the identity function over propositions.

That C is made visible is argued by examples like:

(6) Whan that Aprill with his shoures soote ...

(Chaucer)

There are many variations on this theme and points where exclamatives deviate from "normal"

(embedded) indirect questions, syntactically as well as semantically. I will consider such

deviations in two separate subsections, one for syntax and one for semantics.

2.2.1

Syntactic Specialties

For one thing, in French the customary way to form the exclamative is not as in (5), but as in

(7) (note the stranded adjective in both cases). Swedish has a similar pattern.

(7)

Comme il fait froid!2 / ((Qu’est-)Ce) Qu’il fait froid!

Norwegian has a special "wh- word" reflecting the equative question semantics directly, "så":

(8)

Så lite (som) han forstår!

so little that he understands

How little he knows!

Wie wenig er versteht!

(Corpus original)

(Corpus translation)

(Corpus translation)

The forms in (7) and (8) cannot be embedded under predicates like "ask" or "wonder". But

that is no wonder, since clauses embedded under those predicates have a higher logical type

(in the theory of Groenendijk and Stokhof: <s,<s,t>>) (cannot embed "that" clauses).

The forms in (7) and (8) can to a certain extent be embedded under predicates like "know":

(9)

Elle sait comme il fait froid dehors.

and they can to a great extent be embedded under predicates like "amazing":

(10)

C’est fou comme elle est belle.

C’est fou ce que j’aime cette femme quand elle rit.

(Laurent Réval)

That is not amazing – after all, these predicates seem to mean approximately the same as the

exclamative speech act function.

German has adjective stranding + finite verb raising (V2) as an alternative to (5):

(11)

Heimatliche Natur! Wie bist du treu mir geblieben!

homely

nature how are you faithful me remained

(Hölderlin: Der Wanderer)

There is also the option of "was" (what) instead of "wie" (how):

(12)

Was bist du groß geworden!

what are you big become

This V2 pattern cannot occur embedded. No way.

(13) * Irre, was/wie bist du groß geworden.

crazy what how are you big become

Suggestion:

The syntactic peculiarities of exclamatively used indirect questions

are signs that the clause cannot be embedded

2

Mais le septième trouva Blanche-Neige sur son lit et appela les autres pour la leur montrer;

– Oh! comme elle est belle! dirent-ils tous.

2.2.2

Semantic Specialties

• Not every IQ has the same interpretation as an exclamative as as an embedded question.

• Not every IQ is appropriate as an exclamative (IQ = Indirect Question).

2.2.2.1

Scalar Interpretations

First •: As noted by Elliott (1974), as an exclamative, a wh- word has a scalar interpretation:3

(14)

He may be a genius, but Jesus, how he eats.

(about Duke Ellington)

vs.:

..., but have you noticed how he eats? (nonscalar interpretation possible)

or

..., but do you realize how he eats?

(nonscalar interpretation possible)4

(15)

a.

b.

Quelle voix elle a!

Tu ne sais pas quelle voix elle a.

(only scalar interpretation possible)

(nonscalar interpretation possible)

(15a) seems to mean "that the voice she has is as A as it is" for an underspecified adjective A.

The same sentence in (15b) can have this interpretation, but it can also have a nonscalar one.

(Compare, On sait combien il fait has only a "nonscalar" reading: …

λw t°w = t°v , cf. (5).)

Suggestion:

If a scalar interpretation is available, it is selected because

the utterance communicates that the fact is remarkable

Zanuttini and Portner (2003) encode scalarity in a context change operator Rwidening

(which is supposed to be interpreted into the clause on the basis of pragmatic reasoning).

The IQ is supposed to denote a set of propositions, the set of true answers (Karttunen-style).

Rwidening has a superset condition (i) and an scale condition (ii); jointly they express extremity.

To be precise, let us try to apply these two conditions to the simple case (5). Suppose that "how cold it is" wrt. w and

[0,-10] denotes the set {it is ≤ 0, ..., it is ≤ -9}. Then "R(how cold it is)" wrt. w and [0,-10] must denote a superset,

say, {it is ≤ 0, ..., it is ≤ -11}. But it cannot, because it is in fact only -9. So the superset condition cannot be met.

Suppose now that "how cold it is" wrt. w and [0,-10] denotes {it is ≤ 0, ..., it is ≤ -10}. Then the exclamative can

denote {it is ≤ 0, ..., it is ≤ -11}. But then the sentence "John knows how cold it is" cannot be true, because it is in

fact -11 and John only knows that it is -10. The problem is that both with and without R, the IQ is to denote the whole

set of true answers, still the exclamative is to denote something more extreme than the interrogative.

Thus the theory is incoherent. Generally, I believe it is misguided to try to encode extremity.

It is unnecessary and it seems impossible.

3

4

Milner (1978: 252): Les énoncés exclamatifs expriment "un haut degré dans l’ordre de la quantité ou de la qualité".

Cf. "It’s how I eat, Sir!" (Beggar in Chicago)

2.2.2.2

Plurality and Habituality

2nd •: First, the observation that a floating universal quantifier can be necessary (German):

(16)

Geilo mit wem ich ?(alles) getanzt hab!

Geilo with whom I all danced have

(attested)

This seems to be related to the preference for a scalar reading: The universal indicates a scale.

But there may be more to it than that: Note that when the wh- value is clearly outlined and

thus easily describable, attitudes of the “astonishing” sort are not appropriate:

(17)

a.

b.

c.

d.

It’s Amazing who won ...

(only Google hit "amazing who won")

# It’s amazing who won.

√ It’s amazing that Bush won.

Isn’t it amazing who wins those damn things?

(attested – habitual!)

It might be that invoking a plurality or habituality is a means to evade competition from "that".

In (17d) there is a scale involved, but merely one of likelihood, which should be easy to read

into (17b). What distinguishes (17d) from (17b) is evidently the difficulty of naming the who.

True, an exclamative remains bad. But in German it is ok; cf. (18a). Even (18b) is accepted:

(18)

a.

b.

Also ich weis warum ich den Eurovision Song Contest nicht mag.

Das hatt doch alles nix mit Musik zu tun! Wer da alles gewinnt!

Wer da wieder gewonnen hat!

who there all wins

who there again won

has

Let us say that

•

indirect questions used as exclamatives or under predicates like "incroyable",

as opposed to predicates like "sait", are S-factive: the speaker knows the proposition

Suggestion:

Preferences for habitual or plural interpretations of S-factive IQs can be

explained as effects of a competition with a more specific clause

Nowhere is the competition from "that" clauses stronger than with indirect polarity questions –

a stronger (more specific) presupposition is to be preferred if only it is justified:5

(19)

a.

b.

# Ob die U-Bahn noch fährt!

# It’s incredible whether the tube is still running.

The denotation of the IQ is ‘that the tube is still running iff it is in fact still running’, and since

the speaker knows the proposition that the tube is still running or the proposition that it is not,

the corresponding sentence with "that" has a nonvacuous presupposition and is preferred.6

Conversely, nowhere is the competition from a "that" clause weaker than with degree IQs

where there is no standard scale ("how beautiful", etc.).

5

6

Note a parallel to David Lewis’ "Whether report": # John believes whether it is raining.

This can be made precise in Bidirectional Optimality Theory (BOT) (e.g. Blutner 2000).

3

Apparent type t exclamatives

A common form of exclamatives is the declarative (root) "so" ("si", "so", "så") sentence:

(20)

C’est si bon!

Zum Augenblicke dürft’ ich sagen: Verweile doch, du bist so schön!

(Hornez)

(Goethe)

These are type t sentences. Still, they can evidently be used alongside <s,t> sentences:

(21)

a.

Så kaldt det er!

so cold it is

b.

Det er så kaldt!

it is so cold

(Norwegian)

(21b) can serve the same function as (21a), beside ellipsis:

(21)

c.

– Pourquoi tu as mis ton pull?

– Il fait si froid!

(# – Comme il fait froid!)

(22)

— Å, jeg er så glad for min skjønnhet, å så glad, så glad jeg er!

"Ach, ich bin so froh, weil ich so schön bin, o so froh, so froh bin ich!"

"Oh, I’m so happy about my beauty; oh so happy, so happy am I!"

"Ah! Comme j’aime ma beauté, comme je l’aime, comme je l’aime!"

(Norwegian)

(corpus transl.)

(corpus transl.)

(corpus transl.)

Suggestion:

These sentences generally mean the same as the corresponding IQs

minus the intensionalization.

That is, (21b) denotes the same as the sentence "it is as cold as it actually is"; "so" translates

as λα α ≥ @(α), just like "how", but because it remains in situ and Spec,CP is thus not filled,

the denotation is not a proposition but a truth value – in fact, 1 regardless of the actual world.

This makes the sentence inappropriate as an assertion. So it is lifted to <s,t> by the principle

Intensional Functional Application (cf. footnote. 3), and digested by the exclamative function.

This explains the contrast in (21c): Ellipsis (implicit parce que) contributes intensionalization

and cannot digest a type <s,t> sentence.

4 Conclusions

This is a weak theory of (clausal) exclamatives, postulating nothing, ascribing no more to the

clauses than what we know about them in advance. I seek to attribute the speech act to the

logical type <s,t> assuming only reasonable general conditions of communication; you utter

something because it is worth mentioning, – and calling attention to a true proposition only

makes sense if that proposition is to the speaker’s mind remarkable.7 In a sense, this is what

Rexach (1996) and Zanuttini and Portner (2003) purport to do; – but they do posit something

(EXC as a semantic function, Rwidening as something contained in a clause). In my picture, there

is no direct link between syntax and exclamative speech acts, and the only direct semantic link

is the logical type; the special interpretational properties of exclamative clauses are strategies

designed to enhance remarkability and to evade competition from more specific sentences.

7

Quite literally!

References

Blutner, Reinhard (2000) "Some Aspects of Optimality in Natural Language Interpretation", in

Journal of Semantics 17, 189-216.

Elliott, Dale (1974) "Towards a Grammar of Exclamations", in Foundations of Language 11,

231-246.

Fabricius-Hansen, Cathrine and Kjell Johan Sæbø (2004) "In a Mediative Mood: The Semantics

of the German Reportive Subjunctive", in Natural Language Semantics 12, 213-257.

Gallin, Daniel (1975) Intensional and Higher Order Modal Logic. Amsterdam: North Holland.

Groenendijk, Jeroen and Martin Stokhof (1997) "Questions", in Johan van Benthem and

Alice ter Meulen (eds.), Handbook of Logic and Language, Amsterdam: Elsevier, 10551124.

Gunlogson, Christine (2003) True to Form: Rising and Falling Declaratives as Questions in

English. New York: Routledge.

Karttunen, Lauri (1977) "Syntax and Semantics of Questions", in Linguistics and Philosophy 1,

3-44.

Krifka, Manfred (2001) "Quantifying into Question Acts", in Natural Language Semantics 9, 140.

Michaelis, Laura (2001) "Exclamative Constructions", in Martin Haspelmath et al. (eds.),

Language Typology and Universals: An International Handbook of Contemporary Research,

Berlin: Walter de Gruyter, 1038-1058.

Milner, Jean-Claude (1978) De la Syntaxe à l’interprétation: Quantités, Insultes, Exclamations.

Éditions du Seuil: Paris.

Munaro, Nicola and Hans-Georg Obenauer (2002) "On the semantic widening of underspecified

wh-elements", in Manuel Leonetti, Olga Fernàndez Soriano and Victoria Escandell Vidal

(eds.) Current Issues in Generative Grammar, Universidad Alcalà de Henares - Servicio de

Publicaciones, Madrid, 165-194.

Reis, Marga (1999) "On sentence types in German: an enquiry into the relationship between

grammar and pragmatics", in Interdisciplinary Journal for Germanic Linguistics and

Semiotic Analysis 4, 195-236.

Rexach, Javier Gutiérrez (1996) "The Semantics of Exclamatives", in Edward Garrett and

Felicia Lee (eds.), Syntax at Sunset (= UCLA Working Papers in Linguistics), 146-162.

Schwabe, Kerstin (2004) "German root declaratives and independently used dass complement

clauses", to appear in Valerie Molnár and Susanne Winkler (eds.) Architecture of Focus,

Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter.

Searle, John R. (1976) "A classification of illocutionary acts", in Language in Society 5, 1-23.

Sæbø, Kjell Johan (2001) "The Semantics of Scandinavian Free Choice Items", in Linguistics

and Philosophy 24, 737-787.

Zaefferer, Dietmar (1983) "The Semantics of Non-Declaratives: Investigating German

Exclamatories", in Rainer Bäuerle, Christoph Schwarze, and Arnim von Stechow (eds.),

Meaning, Use, and Interpretation of Language, Berlin: de Gruyter, 466-490.

Zaefferer, Dietmar (2001) "Deconstructing a classical classification. A typological look at

Searle’s concept of illocution type", in Revue Internationale de Philosophie 216, 209-225.

Zanuttini, Raffaella and Paul Portner (2003) "Exclamative Clauses: at the Syntax-Semantics

Interface", in Language 79, 39-81.