GAO NUCLEAR WASTE Further Actions Needed to Increase the

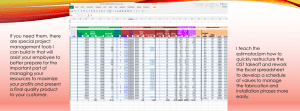

advertisement