GAO RECOVERY ACT Most DOE Cleanup Projects Are

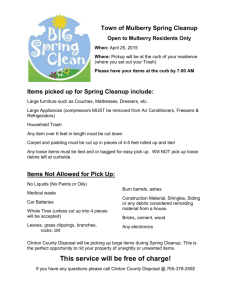

advertisement