DEPARTMENT OF ENERGY Interagency Review Needed to Update

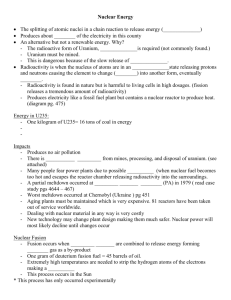

advertisement