GAO/NS&Ab-94-179

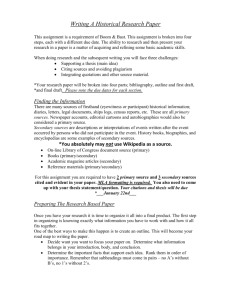

advertisement