Health relationships report

advertisement

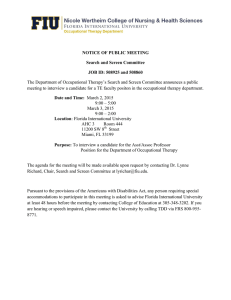

Health relationships report Copyright © RAIL SAFETY AND STANDARDS BOARD LTD. 2013 ALL RIGHTS RESERVED This publication may be reproduced free of charge for research, private study or for internal circulation within an organisation. This is subject to it being reproduced and referenced accurately and not being used in a misleading context. The material must be acknowledged as the copyright of Rail Safety and Standards Board and the title of the publication specified accordingly. For any other use of the material please apply to RSSB's Industry strategy team for permission. Any additional queries can be directed to enquirydesk@rssb.co.uk. This publication can be accessed via the RSSB website: www.rssb.co.uk. Workforce health and wellbeing project Health relationships report Executive summary The purpose of this report is to provoke industry discussion and to provide information to improve the working relationships between rail companies and their health providers. The report studies the relationships between health commissioners and health providers and identifies examples of good practice. It makes a number of recommendations around four key themes for managing occupational health relationships before drawing conclusions on the report's findings. Key theme 1 Contribution of senior clinical and OH leadership to the railway There is no common source of senior specialised clinical advice or leadership within the industry. Health practitioners' day-to-day activities are directed toward meeting the contractual requirements in individual organisations and there is no forum for senior health advisors to focus on strategic decisions. Therefore, industry needs to consider how clinical leadership and senior specialised occupational health advice across the industry can be fostered. New industry leadership approaches could enable health practitioners to tap into advances in clinical practice and health technology. An awareness and understanding of developments in health technology and clinical practice could bring benefits to the rail industry and drive down costs. RSSB and others should work with industry leaders, sponsors and partners to support clinical practice. Key theme 2 - The market for railway OH provision A restricted choice faces rail organisations looking to outsource or re-tender their OH service. Barriers include Link-up accreditation for providers and the distribution of the rail network. Railway organisations need to consider how to facilitate a broader approach to tendering for their occupational health service, so as to ensure that they have sufficient choice and can take advantage of advances in occupational health practice. Key theme 3 Organisational approaches to health management Health commissioners in individual rail organisations should look to improve their commissioning arrangements to ensure: The purchase of a quantum of senior strategic health input That clinical leadership is held to account for health policy at the very top of the organisation RSSB i Health relationships report That services are commissioned to a broader range of interests within railway organisations. Internal organisational arrangements also need to be addressed as there appears to be a poor understanding of the role of occupational health amongst frontline managers, and how to get the best value for money from occupational health professionals and providers. Guidance on provider engagement in the industry may assist with these issues. ii Key theme 4 - Quality assurance and health relationships Health practitioners, especially those working in remote locations or as network physicians, have difficulty in gaining workplace experience in the industry, or obtaining information about it. New and aspirant entrants to the railway industry also struggle to get rapidly up to speed in their knowledge of the industry. The industry needs to consider how it can improve this, so that a wider range of qualified and experienced practitioners are available to the industry. RSSB should work with senior professionals in the industry and the Association of Railway Industry Occupational Health Practitioners (ARIOPS) to develop a suite of supporting information to enable a quality service. Conclusion The railway industry needs to consider its commitment to all of the dimensions of occupational health as set out in the Office of Rail Regulation (ORR) health programme 2010 to 2014. In particular it needs to consider how it can address the challenge of expanding the focus of occupational health to address the adverse effects of work on health and to broaden the approach to wellbeing. A high-profile industry driven initiative similar to the Boorman report process used in the NHS, or Constructing Better Health (CBH) may achieve a sea-change in attitudes and commissioning, especially if tied to government initiatives such as the Public Health Responsibility Deal and was backed by the Department for Transport. A national initiative of this sort will have a short term impact on all organisations but avoid competitive disadvantage and on-going uncertainty as to how to manage health risk. RSSB Table of Contents Health relationships report Executive summary.............................................................................................................i Key theme 1 -Contribution of senior clinical and OH leadership to the railway ................i Key theme 2 - The market for railway OH provision .........................................................i Key theme 3 - Organisational approaches to health management ..................................i Key theme 4 - Quality assurance and health relationships ............................................. ii Conclusion..........................................................................................................................ii Introduction to the Health relationships report...............................................................1 What we mean by 'health'................................................................................................1 Encouraging a culture of excellence in the management of health .................................1 Method.................................................................................................................................2 Survey of OH providers ...................................................................................................2 Survey of OH purchasers ................................................................................................2 Study of comparator organisations ..................................................................................2 Study of the implementation of T663...............................................................................3 Stakeholder views ...........................................................................................................3 The project steering group...............................................................................................3 Contribution of senior clinical and OH leadership to the railway..................................3 Early health relationships in the rail industry ...................................................................3 Occupational health practice before privatisation ............................................................4 Occupational health practice following privatisation ........................................................5 Leadership.......................................................................................................................5 Educational support for railway medicine ........................................................................6 The market for railway OH provision................................................................................7 Responses to restricted OH market ................................................................................8 Wider consequences of restricted OH market .................................................................8 Organisational approaches to health management......................................................10 Tendered outsource ......................................................................................................10 In-house service ............................................................................................................10 Service level agreement/partial in-house ......................................................................11 Health relationships around the response to T663 ........................................................11 Who commissions OH services? ...................................................................................12 Communications and health relationships .....................................................................14 Quality assurance and health relationships ..................................................................16 Qualifications of practitioners ........................................................................................16 Experience, expertise and health relationships .............................................................17 Conclusion........................................................................................................................19 Achieving transformational change in rail health relationships ......................................19 Introduction to the Health relationships report The purpose of this report is to provide information to improve working relationships between rail companies and their health providers. More proactive health management activities with health providers will create improved business benefits for the rail company through more knowledgeable client's contractual requirements. The business benefits gained through healthy staff will be maximised through better health provider contracts. The report studies relationships between health commissioners and health providers to aid the identification of available good practice. What we mean by 'health' Health, as considered in this report, refers to health as categorised by the ORR's occupational health programme 20102014, under three areas: The effect of work on health, including for example, the adverse effects of exposure to dust, asbestos, noise, vibration or the causes of musculoskeletal disorders (MSDs) or work-related stress. Fitness for work including people's fitness for safety critical tasks and covering for example, drugs and alcohol management, and periodic health assessments. General wellbeing, including health and life-style, sickness absence management and rehabilitation. This includes adjustments to the working environment to support people with certain conditions to work effectively, and the rehabilitation of people who have suffered health disorders. Encouraging a culture of excellence in the management of health In its occupational health programme, ORR seeks to stimulate investment in competent health assistance for managers, enabling them to comply with laws aimed at preventing the ill health of employees, as distinct from merely employing professionals to undertake fitness assessments or to provide counselling. Such professionals would support managers in dealing with the effect of work on health and would be an 'intelligent customer' for contracted health services, such as medical fitness. ORR expects organisations to manage health to at least the minimum standard set by law and would regard an excellent organisation as one that delivers compliance with these laws efficiently, and seeks to go beyond the law by investing in rehabilitation and wellbeing amongst other things. ORR makes it RSSB 1 clear that it will enforce compliance where necessary, and highlights work issues affecting health including musculoskeletal disorders, stress, hand arm and whole body vibration, noise, substances hazardous to health (including diesel exhaust), lead, asbestos, and microbes. It also highlights obesity, cardiovascular disease, back pain, fatigue and sleep disorders as health issues impacting on wellbeing, life-style and attendance at work. The present study seeks to evaluate health relationships to uncover and propose good practice to support the development of a culture of excellence in occupational health. 2 Method The study was undertaken by means of a series of semistructured telephone interviews by the contracted health specialist, with key personnel within and outside the railway industry. Organisations were chosen to reflect existing experience in commissioning and providing occupational health to the industry, and also to elicit the views of key stakeholders in the industry. The study also sampled the delivery of occupational health services outside the railway industry. Survey of OH providers A range of occupational health providers were surveyed including: Survey of OH purchasers A range of railway organisations were surveyed, including the Infrastructure maintainer, a not-for-profit organisation, together with an independent commercial infrastructure provider, a freight operating company and a variety of train operating companies. Companies were chosen to reflect both the perspective of longterm franchise holders, and that of organisations where the franchise is close to expiry. Study of comparator organisations Two comparator organisations were studied. One was a large national organisation with personnel distributed throughout the United Kingdom. The other was the NHS; as a large but devolved national organisation, it is reflective of the diversity of occupational health challenges but with a closed culture similar to that of the railway family, and facing a franchised future rather similar to the railway industry. RSSB Large national organisations Smaller organisations, sometimes acting as subcontractors New entrants to the field of railway occupational health Aspirant companies that wish to provide a service but who have so far been unable to acquire business within the sector An in-house provider Study of the implementation of T663 Participants were questioned regarding their awareness of, and any practical steps which they had taken to implement, the RSSB report 'Managing the risk associated with sudden incapacity in safety critical occupations' (T663) as a means of evaluating the scope of their health relationships around the handling of a complex piece of research. Stakeholder views A workshop was held to obtain the views and opinions of the railway trade unions that work across the whole industry, and have a long corporate memory. This was complemented by interviews with two long-standing railway physicians whose experience reflects back before privatisation and both within the main provider since privatisation, and outside this organisation in a governance role within the industry. The project steering group The project was overseen by a steering group made up of senior representatives from within the rail industry. Contribution of senior clinical and OH leadership to the railway There is no structure for a common source of senior specialised clinical advice or leadership at the industry level, nor is there a supportive structure for physicians to provide mentoring or to enhance knowledge of railway medicine. Health practitioners' day-to-day activities are directed toward meeting the contractual requirements in individual organisations and there is no forum for senior health advisors to focus on strategic decisions. This part of the report discusses the background to the current situation, and offers suggestions to address these omissions. Early health relationships in the rail industry The association between railways and health care services began following the opening of the Liverpool and Manchester Railway, in 1830, and as the railways rapidly grew in Britain medical services became an early feature. This was especially because the development of railways involved ambitious engineering and construction work on a scale and at a rate previously unknown, and which had tragic consequences in terms of injury and death to construction workers, operating staff and even passengers. The object of early railway medical services was thus very much focused on treatment to maintain and to restore health, especially after serious accidents, in a workforce which was comparatively well paid but dispersed geographically and away from the traditional centres of medical support in towns and cities. RSSB 3 Gradually in the 20th century, railway medical personnel relinquished their treating roles, as public health services developed, culminating in the establishment of the National Health Service in 1948. The railway medical service then focused on health and work, now known as occupational health. Occupational health practice before privatisation The British Rail Occupational Health Service (BROHS) was established following the nationalisation of the UK's railways in 1948, by the amalgamation of the medical services provided by the predecessor companies. The BROHS was a centralised institution organised on regional lines, with occupational health centres situated in most large cities and railways centres, such as Crewe and York. Each centre had its own medical officer who was supported by nurses and administrative staff, and who undertook responsibility for carrying out pre-employment, periodical and management review medicals in the geographical area surrounding the centre. At this time there was no strong tradition of involvement in health surveillance or wellbeing, as this was in the early days of the Health and Safety at Work Act, and before its more detailed regulations became effective. Railway physicians were trained in the occupational health of the railway by an apprenticeship system, without formalised specialist training. The remit of railway doctors and nurses extended beyond the operation of railways, to hotels and specialised engineering works. Familiar with the environment of the integrated railway, the medical staff would see track workers, signallers, station personnel and train operating crews without any distinction as to their employing organisation. The medical service in this era was directed by a chief medical officer who was accountable to the British Railways Board (BRB). Some of today's concepts of modern railway occupational health, for example the adverse effects of hazardous health issues, or broader consideration of wellbeing, would have been raised by top-down action from the BRB, or by input to the BRB from their medical officers, who met quarterly to compare notes and practice and to discuss medical developments. This structure provided mentorship for new entrants to the field and also created a cadre of senior physicians who provided a body of expertise and clinical leadership to the industry's health function. Medical officers' meetings led to the development and on-going maintenance of the BR railway medical officer's handbook. This 4 RSSB was before the 'clinical effectiveness initiative' transformed medical and health practice; so the informal, non-referenced, consensus-based guidance that it contained was comparable to NHS documents of the time. Occupational health practice following privatisation After privatisation, the railway occupational health service was initially floated as an independent company. In the late 1990s, BUPA obtained the service in its entirety. This included the rights to use the existing medical centres at major stations and railway centres and exclusive access to the former BR railway medical officers' handbook. This handbook was regarded by BUPA as 'commercial in confidence', thus later entrants to the railway occupational health have been denied access to the document. More recently, the new providers of railway OH have built their railway medical structure from scratch, recruiting experienced railway physicians from other providers, or from other railway organisations such as London Underground. Individual occupational health physicians have relied on their understanding of occupational health as practised in other comparator industries, such as road transport or civil aviation. Many of these new entrants have a limited amount of high-quality medical information made available to them by the codes of practice associated with the railway group standards. Some may hold personal copies of the old BR railway medical officer's handbook, but this is now out of date. Leadership Whilst fragmentation of the formally comprehensive and universal occupational health service has led to the loss of continuity, both geographically and in time, it has allowed new providers to bring in some new ideas, and to trial innovative approaches from comparator industries. However, many within the industry and its occupational health providers, remain concerned about the loss of continuity and expertise associated with the experience of the former BROHS. As a result, former railway occupational health physicians formed a small voluntary professional association, which for the most recent five years of its existence has been multi-disciplinary, including nurses and allied healthcare professionals and is now called the Association of Railway Industry Occupational Health Practitioners (ARIOPS). As a voluntary body, ARIOPS has struggled to maintain its role, although it is evident, from the many references to it in official documents, that others in the industry recognise the need for an institution which focusses professional clinical leadership. RSSB 5 Summary 1 Prior to privatisation, the BROHS provided a continuous source of senior specialised advice within the industry and clinical leadership throughout it, which competitive structures subsequent to privatisation have not been able to replicate. Recommendation 1 Industry needs to consider how clinical leadership and senior specialised occupational health advice across the industry can be fostered. This may differ in its priorities from the day- to-day interests of occupational health contractors, but should help rail organisations to focus on strategic issues such as the adverse effects of work on health and the need to develop broader approaches to wellbeing as set out by the ORR. Educational support for railway medicine Within railway occupational medicine, there is no longer a supportive structure for physicians to provide mentoring or to enhance knowledge of railway medicine. Experienced practitioners may move into and out of the industry as frequently as contracts change. The contrast with aviation medicine could not be greater, for aviation medicine enjoys the support of a bespoke examination and specialist field, and is backed by research funding, appropriate academic support and the RAF. By contrast in the UK, academic and research support for railway medicine is almost non-existent, which means that there is no infrastructure to enable benchmarking or evaluation of the effectiveness of existing services or their focus. Case study: A large comparator organisation runs an annual conference to which all of its occupational health practitioners are obliged to send all of their occupational health staff. The conference is provided by the sponsoring organisation but the contractors are expected to release their staff. At this conference, OH professionals are brought together with health and safety and operational and human resource managers and the focus is on company strategy and what the company wants from their providers. Summary 2 6 RSSB In a competitively tendered 'revolving doors' occupational health environment, support of the educational and academic development of the subspecialty of railway medicine within occupational health is difficult. However, it is essential, so as to make sure that industry gains the maximum advantage from changes in clinical practice and health technology. Recommendation 2 RSSB and others should work with industry leaders, sponsors and partners to provide meetings and educational material to support railway occupational health. An example might include sponsorship of a national railway occupational health event to which health commissioners and health providers should be invited or even mandated to attend by sponsoring rail organisations. The excellent conferences and interactive web forum maintained by ALAMA (the Association of Local Authority Medical Advisers) would form a good example, although much larger in scale than anything that the rail industry could sustain though ARIOPS, the comparator organisation. The market for railway OH provision The number of organisations providing occupational health to the railway industry is slowly growing, as the initial provider loses its monopoly influence. A number of customers have sought alternative providers, regarding existing products as insufficiently flexible and responsive to the needs of the industry, particularly as the turnover of TOC franchises brings new ideas and new approaches to management. Despite reluctance due to the logistics involved, they have sought to transfer their service elsewhere but within the rail industry this is not simple. Responses to restricted OH market Two large rail businesses strongly expressed their frustration at the limited choice of provider in commissioning a service throughout the UK, and this difficulty was also apparent in non-rail purchasers with similar needs. One national organisation had got around this difficulty by commissioning from more than one provider. It recognised that only a small localised OH company could provide the bespoke service which it required for a specific site, but the more generic product available from a large national provider was more reliable in dispersed circumstances. Another large (non-rail) business which was generally characterised by a strongly strategic approach to OH had responded to this challenge by building a small in-house team. Wider consequences of restricted OH market The restricted access to the railway occupational health market means that some opportunities for health processes and techniques, which could be of assistance to the industry in managing absence, such as occupational health linked case management, have not materialised. In other cases, a traditional and transactional approach to commissioning and contract management has resulted in the failure make use of senior RSSB 7 clinical personnel to offer strategic advice. This advice could enable things to be done better or more effectively and develop clinical leadership. Case study: an occupational health provider which was not contracted to undertake any railway work, but which would like to get involved, has developed expertise in case management linked to occupational health. As a result, it had managed to reduce sickness absence in an organisation from 6.9% to 4.1%. Summary 3 Providers and purchasers agreed that there was a restricted choice facing rail organisations looking to outsource or re-tender their OH service. This is especially so for purchasers whose businesses are spread widely throughout the UK. This restriction is true for all nationwide organisations, but the special conditions of the rail industry make it even more challenging. The restricted occupational health market also prevents the rail industry from gaining access to some of the more innovative approaches to occupational health provided by outside providers. Recommendation 3 Railway organisations need to consider how to facilitate a broader approach to tendering for their occupational health service, so as to ensure that they have sufficient choice and can take advantage of advances in occupational health practice. Broader approaches might include contracting with more than one organisation to ensure national coverage, or else to gain especial expertise. The need to acquire experience and expertise in the particular requirements of the industry appears to have acted as a barrier to new providers to enter the field, especially as the necessary experience and expertise has to be sufficient to meet such requirements as Link-up audit and accreditation. Case study: when the Safe Effective Quality Occupational Health Service (SEQOHS) system of accreditation for occupational health services was developing, NHS occupational health services felt under some pressure to be in the forefront of this initiative. However the scheme as set out did not include all of the specialised areas relevant to NHS occupational health practice. So it was agreed that the NHS would work with the Faculty of Occupational Medicine, the sponsor of the scheme, to develop health specific domains within the main scheme. 8 RSSB A further barrier to entry to the railway occupational health market exists in the requirement to provide clinics close to railway centres, often located in the centre of cities and distanced from the more provincial industrial or NHS locations of many occupational health providers. Case study: one occupational health provider with considerable experience in railway occupational health commented that they had turned down additional national railway work because of the requirement to provide clinics within walking distance of railway centres. They had worked out that this was not viable unless the work continued for at least two years, and in this case contract was for no more than nine months. Another provider who is outside the railway occupational health field at present, but would like to participate, remarked that they had so far not tendered for railway work because of the requirements for Link-up accreditation and the obligation to provide additional clinic premises near to rail centres in major cities. Summary 4 Recommendation 4 There are two main barriers to creating a wider market in occupational health, these being the need to meet the specific standards in Link-up accreditation and to provide clinics facilities in each and every railway centre. 1 Opening up the accreditation scheme by integrating Link-up into a railway specific domain of SEQOHS (as with NHS occupational health services), should lead to a significant widening of the occupational health provider market 2 Further measures to expand this market might include looking to provide clinic facilities available to rent in railway centres by landlords such as Network Rail, as occurs with other railway related services 3 The rail industry could arrange frameworks to guide OH provider expertise as highlighted in Summary point 2 Organisational approaches to health management There are three business models used to provide an occupational health service. The commonest model is the tendered outsource. Tendered outsource In this model, health relationships are focused on measurable outputs such as KPIs, rather than on higher level outcomes. Clinicians complain that they have no strategic input into the contracts, which may be of short duration. Meetings, when they RSSB 9 take place, in are 'set pieces' between contract managers and rarely involve clinicians. There is a lot of frustration amongst clinicians who feel that their high-level clinical expertise is not being asked for or used, and generally felt like being 'doc in a box' who was taken out for a specific purpose and then put back in the box. Clinicians also describe difficulties in getting close to the business, such as not having access to the company intranet, so they cannot directly access company health and safety policies or business directories. In some cases they are too far removed to be able to request or arrange site visits to familiarise themselves with rail environments. 10 In-house service The least common model is one of in-house provision. In this nurse-managed model, clinical meetings and case conferences are a strong feature, and the involvement of clinicians is much more strategic and is integrated closely with the business. The approach to clinical advice to managers and the business moves beyond the transactional and becomes educational and outcomefocussed. Clinicians are part of the staff of the rail organisation, have access to the company intranet and business directory and access to a driver's cab, to enable them to get close to the working environment. Senior clinicians, including physicians, are available to the business to give strategic advice if required and have been used to help other rail businesses in the same group to manage their outsource requirements. Service level agreement/partial inhouse This model lies between the two models described above, where the relationship is set out in a service level agreement, and depending on the relationship between the customer's representatives and the clinicians, a greater degree of close working is possible than with the total outsource. In this model, clinicians described moving from formalised relationships based entirely around KPIs, towards a collaborative approach, based on mutual respect. Clinicians working in this model described the need for them to work hard on relationships with managers, trade unions, safety personnel and human resource officers to gain acceptance, so that their influence can move from the transactional to the transformational. Health relationships around the response to T663 Research Project T663 - 'Managing the risk associated with sudden incapacity in safety critical occupations' is a complex and innovative piece of research which was published in 2009. This work is one of a number of studies which have been undertaken to help occupational health practitioners and safety professionals to understand some of the health dilemmas faced within the RSSB industry. The project studies the consequences of health risk, and some of its conclusions are quite challenging, but if applied throughout the industry could lead to considerable economy in the interpretation of fitness for safety critical work. However, there is no evidence that the findings of this research have been applied anywhere in the industry, whatever the business model. Implementing this work would require considerable OH knowledge and expertise within rail organisations and close cooperation between risk and safety managers and senior OH clinicians. In fact it is difficult to conceive of any railway organisation being capable of implementing and operationalizing the consequences and finding of this study, without having its own company medical officer for reference. Case study: one large national organisation, which outsources its occupational health to a number of contractors, also employs a senior chief medical officer to coordinate health activities throughout the organisation. This physician reports to and has a place on the company's board and is able to ensure that health issues are dealt with at the very highest level. He is also able to manage complaints against the contractors, and to take those decisions personally which will have expensive consequences for the company such as ill-health retirements. He also ensures that the OH contractors are fully signed-up with regards to company health policy by coordinating conferences and providing educational material. Another large rail organisation has recently appointed a chief medical officer with a similar remit; an important part of their work will be to ensure compliance by of the outsourced occupational health providers. Summary 5 The broad knowledge and experience of clinicians can respond to the challenges facing the industry to address the adverse effects of work processes and workplace hazards on employees. This may also include the wider determinants of wellbeing as identified by the Office of Rail Regulation (ORR) occupational health programme. The broader utilisation of clinicians can be seen in the in-house model, and a major challenge is to ensure that this strategic wealth of knowledge is also made available where the choice has been made to outsource occupational health. Recommendation 5 Health commissioners in individual rail organisations should ensure that their commissioning arrangements include the RSSB 11 purchase of a quantum of senior strategic health input to provide clinical leadership to enable the organisation to: 1 Deal with wider issues including the scope of occupational health service, integration of health research such as 'Managing the risk associated with sudden incapacity in safety critical occupations' (T663) and advice on specific strategic issues 2 Ensure that wider health issues (including the adverse effects of work hazards and processes on staff health and the broader determinants of wellbeing) are addressed seriously 3 Ensure that health policy is held to account at the very top of the organisation Who commissions OH services? It is natural that occupational health provision will focus on those areas that are close to the hearts and mind of the sponsoring part of the commissioning organisation. Occupational health services are in general commissioned through human resources rather than health and safety departments and so occupational health professionals are largely accountable to HR departments. Priorities through them focus on operational management responsibilities for implementation of medical fitness decisions made under the railway group standards. Thus, railway occupational health is focussed on attendance management and fitness of safety critical personnel to undertake their work. Occupational health professionals described little direct contact with safety personnel, and in many cases, were not aware of risk assessments and direct involvement of occupational health professionals with risk and safety professionals. Clinicians are thus subservient to sponsors, so are not able to, for example, initiate health surveillance, or to take a broader approach to wellbeing as advised by ORR. ORR has indicated that their inspections will 'evaluate compliance with the law applicable to the particular health risk and take enforcement action in line with our enforcement policy statement to secure any necessary improvements'. It is obviously important that contracting arrangements enable occupational health to play their part in ensuring compliance - not to do so will put their own health practitioners at some risk with clinical governance processes as applied to health practitioners. OH practitioners may find themselves in a difficult ethical situation when they have identified a medical condition caused by work, but where a 12 RSSB suitable risk assessment had not taken place and they know the issue has not been strategically managed. Case study: In the case of Thomas, Studholme and Rogan v Arriva, Swansea County Court, 30th November 2009, His Honour Judge Vosper QC found for the claimants (three train drivers) who claimed that they suffered with Carpal Tunnel Syndrome, caused by their work. He also commented "That the defendant failed in its duty of care towards each of the claimants in failing to risk assess the work system. Any such assessment should have identified the shortcomings in the ergonomic conditions of the cab and observed the individual habits of drivers which gave rise to risk of injury. There was then a failure to take even the most modest of measures to prevent or significantly reduce the risk of injury to the drivers (that is, to fit and maintain adequate seating and arm rests). The study found little evidence of occupational health participation in health surveillance, suggesting that either risk assessments were not revealing any need for it, or else risk assessments were not sufficient or extensive enough. This is worrying for outsourced OH services as they may still share liability for any subsequent claims. Case study: One of the OH providers revealed that they had been advised by their solicitors that they had to pay a share in the settlement of a claim for Hand Arm Vibration Syndrome brought against a large local authority where they had been the OH provider, even though the employer had 44,000 employees and its safety officers and managers had been responsible for undertaking the risk assessments. Summary 6 Occupational health in the rail industry tends to be commissioned and accountable to operational managers and human resource departments where it is measured and delivered in a transactional fashion and focusses on sickness absence and safety critical fitness. Hence the adverse effects of work hazards and work processes on health and the broader determinants of wellbeing, which may be held elsewhere in railway organisations (for example with safety and risk managers) tends to be underplayed. This is important in itself but change is also needed to avoid enforcement action and to prevent the clinical governance support for the health practitioners being compromised. RSSB 13 Recommendation 6 Rail industry health commissioners need to ensure that commissioning processes for occupational health are structured so that services are commissioned and therefore accountable to a broader range of interests within railway organisations, including safety and risk departments. This will ensure that the broader perspectives of occupational health as seen and set out by the ORR are fully addressed. RSSB and others might consider developing guidance on good commissioning in the industry jointly with occupational health bodies such as the Faculty of Occupational Medicine and/or the Society of Occupational Medicine. Communications and health relationships Communications difficulties between providers and contracting organisations were observed on various levels. It was apparent that there is a gap in understanding when considering railways and medicine, both of which have strong cultures that are very different from each other. Railways have a tradition based on rules and certainties, whereas medicine concerns opinion and probability, the two disciplines perhaps overlapping in the concept of risk assessment. Rail managers often felt that they did not get the answers that they wanted from occupational health management reports and that such reports too often reflected the wishes and views of the employee rather than their own. Clinicians commented that too often managers failed to ask clear and direct questions and failed to give more than the most minimum of information about their employees. They also commented that line managers also sometimes failed to understand exactly what an OH report actually says. Occupational health reports advise managers and others of the implication of adverse health on an individual's ability to undertake their work or on the adverse effects of their work on their health. Because of the potential for the findings to impact on the individual's employment status or to initiate a legal claim, they can be quite sensitive documents and hence the language used is often quite subtle. Case study: A senior clinician commented that if the only clear information that they got was from the employee, it was hardly surprising that OH reports could appear to mostly reflect this input. 14 RSSB It seems there is a need for work in educating line and other managers in the industry, to ensure that they get good value for money out of their referrals. There is also scope for educating trade union representatives in the role of occupational health and how they can best support those members who need OH opinions. Case study: One large but dispersed non-rail organisation has established a case referral unit, manned by human resource officers working as case managers. As case managers they work with and supervise line managers in completing OH referrals and in interpreting their reports. They work closely with occupational health and are able to interpret reports and explain their significance to managers who may only very occasionally make referrals. Summary 7 Recommendation 7 Quality assurance and health relationships There appears to be a poor understanding of the role of occupational health amongst the frontline managers, and how to get the best value for money from occupational health professionals and providers. This will often require greater commitment in completing referral forms and providing the occupational health professional with sufficient information to be able to make a balanced judgements and recommendation. 1 It is recommended that occupational health commissioners take action to ensure that their line managers and other occupational health referrers understand the purpose of occupational health and how to make good occupational health referrals; including what information the clinician needs to give a cogent report and how to read and interpret that report. 2 RSSB or others might wish to consider commissioning joint work with bodies such as the Faculty or Society of Occupational Medicine to develop guidance for managers on completing referral forms for occupational health opinion. Many highly qualified clinicians employed within occupational health providers are frustrated that they are unable to work in an influencing way. Frequently, their input to the industry is restricted to giving clinical opinions in what are sometimes very narrow circumstances. OH practitioners may find it hard to gain RSSB 15 experience and knowledge to provide improved value to the industry. Qualifications of practitioners Occupational health providers surveyed demonstrated a very high level of qualifications in doctors and nurses. In no cases was there any evidence of substitution of low qualifications (for example, GPs with diploma instead of specialist accredited consultant doctors) or substitution of cheaper professionals (for example, replacement of nurses with technicians) which is otherwise common in occupational health provision. The high level apparent in railway contracts is unusual in occupational health and demonstrates the seriousness with which existing providers approach the industry. However in many cases, the response of managers and commissioners suggested that they were unaware of the senior skills and experience of the practitioners contracted to them. Some of the more experienced OH professionals expressed frustration that commissioners and managers did not understand the level of experience, training and expertise available to them. Within this specialist clinical workforce a more strategic input into employee health, beyond that currently provided by management referrals and periodical reviews, could be made. However, contract management processes such as KPIs just count consultations and form a barrier in utilising clinicians in this way. Strategic input might enable commissioners to obtain a more targeted and cost effective service. In those settings both inside the railway industry and outside of it, where occupational health is at least partially an in-house function, it was evident that senior clinicians were involved at a much higher level in the business. This level of input meant that they were able to influence all of its policies in such a way that health was integral to the organisation's strategy. Case study: an in-house provider of occupational health remarked that because of their status they enjoyed a wide influence within the company which was growing as they continued to educate their colleagues in what could be achieved from good occupational health practice. Their involvement included participation in staff conferences, intranet, staff magazines etc. 16 RSSB Summary 8 Many senior clinicians employed within occupational health providers are frustrated that they are unable to work in an influencing way. Their input into the industry is almost entirely restricted to giving clinical opinions in what are sometimes very narrow circumstances, against referrals which are lacking in detail and focus Recommendation 8 Commissioners and providers of occupational health need to find ways of enabling their senior clinicians to work more strategically with senior operational, human resource and safety managers. These might include: 1 Regular quarterly health strategy meetings including lead physicians, safety and human resource managers. 2 Inclusion of senior clinicians in media including staff conferences intranet and company magazines. 3 Involvement and inclusion of senior clinicians in one-off programs tackling issues where health may be a concern. Experience, expertise and health relationships Gaining access to the industry to understand its organisations is much harder now than in the days of the integrated and nationalised railway with its in-house occupational health service. As occupational health provision to the industry has diversified, practitioners find it much harder to gain experience and knowledge to provide improved value to the industry. Most of the large occupational health providers have made some effort to ensure the exposure of their practitioners to the working railway environment, either through informal educational experience or workshop visits. However, this experience is not available to those providers or practitioners who have yet to secure a significant foothold in the industry. Information could be made available to improve this situation, for instance, formal track awareness courses exist and their availability could be better promulgated to OH providers. Organisations such as ARIOPS or RSSB could also make educational material available through their website or clinical forum and conferences. This information should be available to clinicians who aspire to work in the industry as well as those who actually do so, without distinction. Few providers appeared to have access to their commissioners' intranets, and this prevents clinicians from gaining access to the non-physical aspects of their commissioners businesses such as: Understanding the structure of the business through the management tree RSSB 17 Becoming aware of important contracts inside the business Being able to view highly relevant documents such as safety and human resource policies Much of the day-to-day business of railway occupational health consists of giving opinions regarding fitness to commence or return to work in safety critical positions. Whilst observing the workplace is ideal and important, it will never be feasible for this to be part of every consultation. The industry is almost unique in its history of documenting and recording every aspect of its structure and equipment, and this information could be made more readily available to occupational health practitioners so that they understood the differences between the various workplaces. Much of this information is already available in other places within the industry, and with a degree of effort could be made available through IT to occupational health practitioners. Good practice identified in the study, included the making available of cab passes to encourage railway practitioners to observe the workplace of drivers. Summary 9 Railway occupational health practitioners especially those working in remote locations or as network physicians, have difficulty in gaining workplace experience in the industry, or obtaining information about it. The industry needs to consider how it can improve this, so that a wider range of qualified and experienced practitioners are available to the industry. Recommendation 9 Railway organisations need to look carefully at how to enable railway occupational health practitioners to better understand the industry in which they work. This may include: 1 Cab rides, visits to signalling and control centres, and track awareness courses are obvious opportunities. 2 Measures such as making intranet material available to occupational health practitioners (including guidance material regarding locomotives, multiple units, carriages and stations), together with health, safety and human resource policies. RSSB should work with senior professionals in the industry and ARIOPS to develop a suite of supporting information, to enable new and aspirant entrants to the railway industry to get rapidly up to speed in their knowledge of the industry. 18 RSSB Conclusion It is clear from studying a number of documents published by RSSB and ORR that there has been an interest in advancing OH in the rail industry over the last ten years. Both RSSB and ORR have published guidance on OH which is available on their websites. Yet OH provision has failed to expand to fill some of the gaps identified by ORR in its occupational health programs 2010 to 2014. There has been much consideration about setting up a railway occupational health advisory board, but it is difficult to see how such a body could on its own achieve the radical change in occupational health relationships which are the focus of this study. This discussion might lead to more successful and enduring outcomes if it could become joined up and networked across the industry to promote a higher common standard rather than pockets of attainment. Achieving transformational change in rail health relationships What is required is a greater commitment to providing a broader focus of occupational health from railway organisations. CBH appears to have achieved this in the construction industry and because of the crossover between construction and rail infrastructure, this initiative does seem to have some influence in the railway industry. Significantly, one of the providers and one of the commissioners outside of the infrastructure organisations agreed that insufficient focus was being made on compliance with the effect of work on health issues, and the research suggested that this position was common and not unique. Case study: a senior officer in a rail undertaking commented that he regarded his organisation as 'barely compliant' with regard to health issues. The provider organisation for the same undertaking expressed equal concerns as to the sufficiency of risk assessments of health issues, as it appears that little health surveillance is taking place in that undertaking. Ultimately the ORR as regulator can take enforcement action if it feels that compliance is insufficient. Increasing spend on occupational health has a short-term consequence for railway organisations, but in reducing sickness absence, promoting health and wellbeing and reducing harm to workers through workplace hazards, an overall improvement in costs across the industry can be expected, which will help to contribute to savings in costs expected by the McNulty report. Another large organisation outside the railway has also had to address its internal concerns regarding the sufficiency of its approach to workplace health, as the next case study illustrates. RSSB 19 Case study: about five years ago, amid growing concern regarding the relationship between work and health the Department of Health needed to consider whether its own occupational health services for the NHS were fit for purpose. The Department of Health provided the necessary clinical leadership to encourage the improvement and development of workplace health services for which they should be an exemplar. They therefore commissioned a senior occupational physician from outside the NHS, Dr Steve Boorman, to examine the service, report and to make recommendations on it. He did this just at the time that the SEQOHS accreditation scheme was being introduced. This was a high-profile investigation and report, and the work looked closely at NHS services and considered them both strategically and pragmatically. As a result of this stimulus, the NHS moved quickly to implement the SEQOHS scheme, and to consider reconfiguration of services where appropriate so as to achieve optimal outcome and efficiency. Summary 10 The railway industry needs to consider its commitment to all of the dimensions of occupational health as set out in the ORR Health Programme 2010 to 2014. In particular it needs to consider how it can address the challenge of expanding the focus of occupational health to address the adverse effects of work on health and to broaden the approach to wellbeing. Ultimately ORR has the sanction of enforcement action, but this is the least desirable approach. A high-profile industry driven initiative similar to the Boorman report process used in the NHS, or CBH may achieve a step-change in attitudes and commissioning. This would be more effective if tied to government initiatives such as the Public-Health Responsibility Deal and backed up by senior national figures such as Dame Carol Black and the Department for Transport. A national initiative of this sort, will have a short term impact on all organisations but avoid competitive disadvantage, which would itself be a risk if decisive action from the industry regulator were to take place. Recommendation 10 20 RSSB The rail industry should consider undertaking a national initiative on the scale of CBH or the Boorman Report to encourage the industry to commit itself to a greater focus on all of the issues of occupational health as set out by ORR (not just safety critical fitness and sickness absence). This would mitigate the risk to the industry from a higher profile approach from the regulator through enforcement action and reduce health risks thus far accepted by industry. RSSB 21 22 RSSB RSSB Workforce health and wellbeing project Block 2 Angel Square 1 Torrens Street London EC1V 1NY enquirydesk@rssb.co.uk www.rssb.co.uk