Managing Conflict of Interest in AHCs to Assure Healthy Industrial and

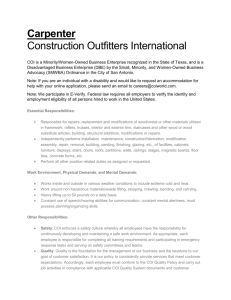

advertisement