Global Jurist Advances International Arbitration and the Quest for the Applicable Law

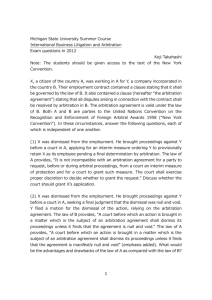

advertisement