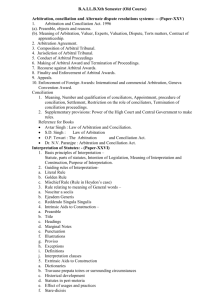

LECTURES ON INTERNATIONAL COMMERCIAL LAW Giuditta Cordero Moss

advertisement