Technology and Assessment Study Collaborative

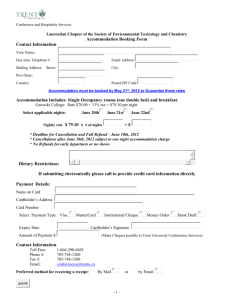

advertisement