Robert Lee Metcalf for the degree of presented on

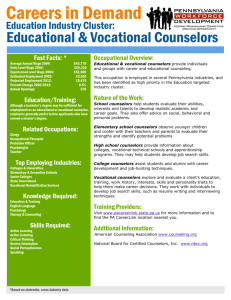

advertisement