Walter T. Kawamoto for the degree of Masters of Science...

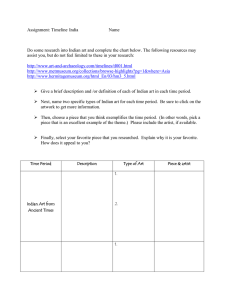

advertisement