Document 11405975

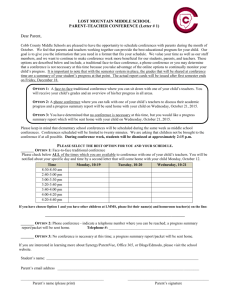

advertisement