Microwave and Quantum-Chemical Study of Conformational ‑Hydroxy-3-

advertisement

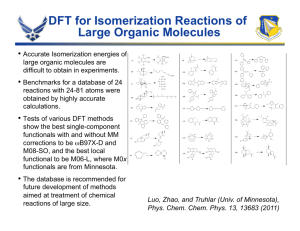

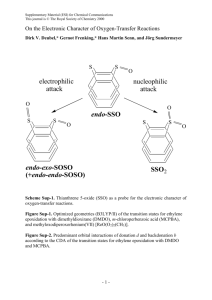

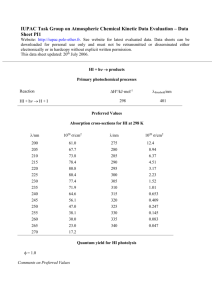

Article pubs.acs.org/JPCA Microwave and Quantum-Chemical Study of Conformational Properties and Intramolecular Hydrogen Bonding of 2‑Hydroxy-3Butynenitrile (HCCCH(OH)CN) Harald Møllendal,*,† Svein Samdal,† and Jean-Claude Guillemin‡ † Centre for Theoretical and Computational Chemistry (CTCC), Department of Chemistry, University of Oslo, P.O. Box 1033 Blindern, NO-0315 Oslo, Norway ‡ Institut des Sciences Chimiques de Rennes, École Nationale Supérieure de Chimie de Rennes, CNRS, UMR 6226, 11 Allée de Beaulieu, CS 50837, 35708 Rennes Cedex 7, France S Supporting Information * ABSTRACT: The microwave spectra of 2-hydroxy-3-butynenitrile, HCCCH(OH)CN, and a deuterated species, HCCCH(OD)CN, have been investigated in the 38−120 GHz spectral region. Three rotameric forms, each stabilized by intramolecular hydrogen bonds, are possible for this compound. The hydrogen atom of the hydroxyl group is hydrogen-bonded to the π electrons of the alkynyl group in one of these conformers, to the π electrons of the cyano group in the second rotamer, and to both of these groups simultaneously in the third conformer. The microwave spectra of the parent and deuterated species of last-mentioned form have been assigned, and accurate values of the rotational and quartic centrifugal distortion constants of these species have been determined. The spectra of two vibrational excited states of this conformer have also been assigned, and their frequencies have been determined by relative intensity measurements. Quantumchemical calculations at the MP2/cc-pVTZ and CCSD/cc-pVQZ levels were performed to assist the microwave work. The theoretical predictions were generally found to be in good agreement with observations. ■ CH3CH(OH)CN,23,24 and (CH3)2C(OH)CN25 as well as the alkynes HOCH 2 CCH, 26 H 3 CCH(OH)CCH, 27 HOCH2CH2CCH,28,29 and HOCH2CH2CH2CCH.9 The situation in HBN is more complex than in these compounds because both the nitrile and alkynyl groups can be involved in internal hydrogen bonding. Rotation about its C−O bond may in fact lead to the three rotameric forms depicted in Figure 1, with atom numbering indicated on conformer I. The H7−C2−O8−H9 dihedral angle can conveniently be used to describe the conformational isomerism. This angle is about +60° in I, approximately 180° in II, and near −60° in III. One intramolecular hydrogen bond between H9 and the π electrons of the C1N6 triple bond is present in I. A similar situation is found in III, where H9 is hydrogen-bonded to the π electrons of the C3C4 triple bond. In conformer II, H9 is hydrogen-bonded to both of these triple bonds at the same time. It should be noted that HBN is chiral and exists in the mirror-image R and S configurations, whose corresponding conformers have identical MW spectra. Figure 1 shows the molecule in the S configuration. There is another important reason for undertaking a study of HBN: Cyanohydrins are versatile building blocks in organic synthesis,30−32 but only a few gas-phase conformational and structural studies have been reported for them.22−24 Further INTRODUCTION Intramolecular hydrogen bonding has for a long time been a favorite research theme of the Oslo laboratory, and a number of hydrogen bonds with a wide variety of hydrogen donors and acceptors have been investigated over the years. In the past several years, we have reported microwave (MW) spectra of the following molecules having internal hydrogen bonds: 2isocyanoethanol (HOCH2CH2NC),1 2-aminopropionitrile (H2NCH(CH3)CN),2 (2-chloroethyl)amine (ClCH2CH2NH2),3 (chloromethyl)phosphine (ClCH2PH2),4 propargylselenol (HCCCH2SeH),5 2-propene-1-selenol (H2CCHCH2SeH),6 2,2,2-trifluoroethanethiol (CF3CH2SH),7 3-butyne-1-selenol (HSeCH2CH2CCH),8 4-pentyn-1-ol (HOCH2CH2CH2CCH),9 (Z)-3-mercapto-2propenenitrile (HSCHCHCN),10 (Z)-3-amino-2-propenenitrile (H 2 NCHCHCN), 1 1 3-butyne-1-thiol (HSCH2CH2CCH),12 (methylenecyclopropyl)methanol (H2CC3H3CH2OH),13 2-chloroacetamide (ClCH 2 CO NH 2 ), 1 4 an d cyclopr opy lm et hy lseleno l (C3H5CH2SeH).15 References to earlier work by us and others are found in these papers as well as in several reviews.16−20 The cyanohydrin 2-hydroxy-3-butynenitrile, HCCCH(OH)CN, henceforth denoted as HBN, was chosen for study this time. It is well-established that the π electrons of nitrile (R−CN) and alkynyl (R−CC−R′) groups can act as acceptors in intramolecular hydrogen bonds where an alcohol group is proton donor. Examples include the nitrile HOCH2CH2CN21 and the cyanohydrins HOCH2CN,22 © 2015 American Chemical Society Received: November 11, 2014 Revised: January 2, 2015 Published: January 5, 2015 634 DOI: 10.1021/jp5112923 J. Phys. Chem. A 2015, 119, 634−640 Article The Journal of Physical Chemistry A on one side and glacial acetic acid (8.0 mL) on the other side were introduced simultaneously via the two dropping funnels over the course of 20 min. The suspension, stirred at room temperature for 5 h, turned brown. It was then filtered, and the solid was washed with 50 mL of ether. The yellow solution was washed with water (4 × 20 mL) and brine (1 × 20 mL) before drying over magnesium sulfate and evaporation of the solvent in vacuo. Purification was performed by slow distillation on a vacuum line (0.1 mbar) with gentle heating of the yellowbrown liquid to 40 °C and selective trapping of the colorless cyanohydrin in a trap immersed in a bath cooled at −15 °C. Yield: 5.67 g (70 mmol, 70%). This cyanohydrin can be stored for months at −20 °C. 1H NMR (CDCl3, 400 MHz) δ 2.80 (d, 1H, 4JHH = 2.6 Hz, CCH), 4.27 (d, 1H, 3JHH = 6.8 Hz, OH), 5.23 (dd, 1H, 3JHH = 6.8 Hz, 4JHH = 2.6 Hz, CHO). 13C NMR (CDCl3, 100 MHz) δ 50.7 (1JCH = 157.5 Hz (d), OCH), 75.3 (2JCH = 51.3 Hz (d), CCH), 76.8 (1JCH = 257.5 Hz (d), CCH), 115.8 (CN). The deuterated species HCCCH(OD)CN was produced by conditioning the MW cell with heavy water and then introducing the parent species. This resulted in roughly 50% exchange of the hydrogen atom of the hydroxyl group with deuterium. Spectroscopic Experiments. The vapor pressure of HBN is roughly 25 Pa at 22 °C. The spectrum was recorded at a pressure of 5−10 Pa. The samples of HBN were stored in a freezer at −80 °C. They had to be warmed to room temperature in order to fill the MW cell with fresh sample. During this process, the compound decomposed partly to propynal and hydrogen cyanide, both of which were identified by their reported MW spectra.42−46 The intensity of the spectrum of propynal increased by a factor of 3 in the cell over the course of 20 min, which showed that the decomposition continued in this environment, possibly catalyzed by the cell walls. The cell was therefore filled frequently with fresh portions of HBN. The MW spectrum was recorded using the Stark MW spectrometer of the University of Oslo described in detail elsewhere.47 Only salient features are reported here, namely, the accuracy of this spectrometer, which is 0.10 MHz for isolated lines, and the resolution, which is about 0.5 MHz for strong transitions. Measurements were made in the 38−120 GHz spectral region. Radiofrequency microwave doubleresonance (RFMWDR) spectra48 were recorded to obtain unambiguous assignments of selected transitions. Figure 1. Models of three conformers of 2-hydroxy-3-butynenitrile. Atom numbering is given on conformer I. The MW spectrum of II was assigned. studies, such as the present, might help us understand better the chemical behavior of this important functional group. It should also be mentioned that cyanohydrins are of astrochemical interest. It has already been shown that the simplest cyanohydrin, hydroxyacetonitrile (HOCH2CN), is formed under astrophysical-like conditions from formaldehyde (H2CO) and hydrogen cyanide (HCN).33 Formally, HBN can be considered to be a hydrogen cyanide adduct to propynal (HCCCHO). Propynal is an interstellar compound,34−36 which is also the case for the hydrogen cyanide molecule, which is ubiquitous in the universe.37 The present study of its rotational spectrum should be very helpful for a potential future identification of interstellar HBN. The several interesting aspects of HBN motivated this first MW investigation. MW spectroscopy was chosen as our method of investigation because of its unsurpassed accuracy and resolution, which is ideal for this type of studies. The MW investigation was assisted by advanced quantum-chemical modeling, which is very useful for the assignment of complex MW spectra because rather accurate values of spectroscopic constants can be predicted in this manner and can be of considerable use in the assignment procedure. Information about parameters that cannot be obtained experimentally can also be derived from these calculations, allowing a more profound analysis of the problem at hand. ■ ■ RESULTS Quantum-Chemical Calculations. Frozen-core MP249 and CCSD50−53 computations were executed using the Abel cluster of the University of Oslo. The MP2 calculations were performed with the Gaussian 09 suite of programs54 while the CCSD computations were done employing the Molpro program,55 observing the default convergence criteria of the two programs. The correlation-consistent cc-pVTZ triple-ζ and cc-pVQZ quadruple-ζ basis sets56 were employed in the MP2 and CCSD calculations, respectively. An MP2/cc-pVTZ potential function for rotation of the hydroxyl group (Figure 2) was obtained by stepping the H7− C2−O8−H9 dihedral angle (see Figure 1) in 10° intervals with all of the remaining structural parameters allowed to vary freely. This function has three minima corresponding to conformers I−III. The MP2 structure of each conformer was optimized, and the results are given in Tables S1−S3 in the Supporting EXPERIMENTAL SECTION Synthesis. A racemic mixture of HBN was synthesized (Scheme 1) as previously reported38,39 with some small Scheme 1 modifications. Into a 250 mL three-neck flask equipped with a magnetic stirring bar, a nitrogen inlet and two dropping funnels were introduced dry powdered sodium cyanide (0.163 mol, 8.0 g) and dry diethyl ether (125 mL). The suspension was cooled to 0 °C, and 1 mL of glacial acetic acid was added. Propiolaldehyde40,41 (0.10 mol, 5.4 g) in 10 mL of diethyl ether 635 DOI: 10.1021/jp5112923 J. Phys. Chem. A 2015, 119, 634−640 Article The Journal of Physical Chemistry A Table 1. CCSD/cc-pVQZ Structures of Conformers I, II, and III of HCCCH(OH)CN I C1−C2 C1−N6 C2−C3 C2−H7 C2−O8 C3−C4 C4−H5 O8−H9 C1−C2−C3 C1−C2−H7 C1−C2−O8 C3−C2−H7 C3−C2−O8 H7−C2−O8 C2−O8−H9 C2−C1−N6 C2−C3−C4 C3−C4−H5 Figure 2. Relative MP2/cc-pVTZ electronic energy as a function of the H7−C2−O8−H9 dihedral angle. Information. The MP2 computations predict that the global energy minimum occurs for II at an H7−C2−O8−H9 dihedral angle of 185.7° (−174.3°), whereas this angle is 59.6° for I and 284.4° (−75.6°) for III. Conformer II has an MP2 electronic energy that is 6.91 kJ/mol less than the energy of I and 6.65 kJ/ mol less that that of III. Upon correction for zero-point vibrational effects, these differences become 6.30 and 5.79 kJ/ mol, respectively. The potential function has three maxima (transition states). The characteristics of these transition states were calculated at the MP2 level, and the results are displayed in Tables S4−S6 in the Supporting Information. The transition states are located at H7−C2−O8−H9 dihedral angles of 111.3, 256.2, and 355.4° with electronic energies that are 10.47, 7.16, and 12.10 kJ/mol higher than the energy of the global minimum, respectively. MP2 calculations were also undertaken to obtain harmonic and anharmonic vibrational frequencies, the vibration−rotation constants (the α’s),57 the Watson quartic and sextic centrifugal distortion constants,58 the rotational constants r0 and re, and dipole moments (see Tables S1−S3 in the Supporting Information). The procedure recommended by McKean et al.59 was followed when calculating the α’s and the centrifugal distortion constants. The optimized CCSD/cc-pVQZ structures of I−III are listed in Table 1. Further details of the CCSD calculations are listed in Tables S7−S9 of the Supporting Information. Table 2 contains the rotational constants calculated from the CCSD structures, the MP2 quartic centrifugal distortion constants,58 the CCSD dipole moments, and the CCSD electronic energy differences. A few remarks on the CCSD structures are in order. The O8−H9 bond length is 95.8 pm in all forms of HBN (Table 1), which can be compared with the equilibrium O−H bond length in methanol (95.6 pm).60 The slight elongation of this bond length from its value in methanol is expected for the title compound because of the internal hydrogen bonds in the three conformers. The CCSD bond lengths of the C1N6 triple bond are 115.1−115.0 pm, while re = 115.54 pm has been reported for the CN bond in CH3CN.61 The re value of the C3C4 triple bond in acetylene is 120.289 pm,62 which slightly longer than the bond lengths of 119.9−120.0 pm found in the present case. The CCSD method predicts II to be the global minimum (Table 2). The electronic energies of I and III are 6.08 and 5.73 kJ/mol higher, respectively. These values are very similar to the II Bond Distances (pm) 148.5 148.5 115.1 115.1 146.6 147.1 109.3 108.9 140.6 140.3 119.9 120.0 106.2 106.2 95.8 95.8 Bond Angles (deg) 110.5 109.9 106.7 107.2 111.3 111.4 108.3 109.1 108.9 113.2 111.1 105.8 108.5 108.6 178.1 178.5 178.4 177.0 179.4 179.9 Dihedral Angles (deg) −59.7 70.0 178.2 −54.5 59.0 −173.8 −58.5 70.0 177.9 −54.3 177.9 −54.3 C1−C2−O8−H9 C3−C2−O8−H9 H7−C2−O8−H9 N6−C2−O8−H9 C4−C2−O8−H9 H5−C2−O8−H9 III 147.7 115.0 147.1 109.3 140.8 120.0 106.2 95.8 110.7 106.7 107.3 108.3 112.9 110.9 107.8 179.4 176.7 179.0 168.8 46.7 −75.1 169.4 45.6 45.5 Table 2. Theoretical Parametersa of Spectroscopic Interest of Conformers I, II, and III of HCCCH(OH)CN I A B C DJ DJK DK d1 d2 μa μb μc μtot ΔE II Rotational Constants (MHz) 5909.8 5773.6 2856.6 2881.4 2026.2 2038.4 1.39 1.42 −8.03 −7.31 27.2 23.8 −0.597 −0.600 −0.0369 −0.0406 Dipole Moments (Db) 1.83 3.23 1.42 0.51 1.69 0.08 2.87 3.27 Relative Electronic Energiesc (kJ/mol) 6.08 0.0 III 5938.5 2852.7 2027.7 1.36 −7.64 26.6 −0.582 −0.0393 4.38 1.31 1.43 4.78 5.73 a CCSD/cc-pVQZ rotational constants, dipole moments, and relative electronic energies and MP2/cc-pVTZ centrifugal distortion constants are shown. b1 D = 3.33564 × 10−30 C m. cRelative to conformer II. Not corrected for zero-point vibrational effects. MP2 results above. The lower energy of II relative to I and III may reflect the fact that H9 is simultaneously bonded to two πelectron systems in II, whereas only one hydrogen bond is present in the two other conformers. The prediction that I and III have nearly the same energy indicates that the hydrogen bonds in these two conformers have similar strengths. 636 DOI: 10.1021/jp5112923 J. Phys. Chem. A 2015, 119, 634−640 Article The Journal of Physical Chemistry A Assignment of the Ground-State Spectrum of II. The decomposition of HBN to propynal and hydrogen cyanide was a severe complication because propynal has a very strong MW a-type R-branch spectrum as well as a weaker b-type spectrum, resulting in a dense spectrum over the entire investigated spectral interval (38−120 GHz). Propynal also has several low vibrational frequencies, and the MW spectra of excited states of these vibrations added to the spectral richness. All of this resulted in numerous overlaps with transitions of HBN. It was also unfortunate that most of the transitions belonging to propynal are much stronger than those of HBN. Another negative factor was that the decomposition of HBN resulted in a relatively rapid increase in the intensity of the propynal lines accompanied by a simultaneous reduction in the intensities of the HBN transitions. It can be seen from Table 2 that the lowest-energy conformer II has a comparatively large μa component of about 3.2 D, while μb and μc are much smaller. We therefore concentrated on finding a-type R-branch lines of this conformer using the rotational and quartic centrifugal distortion constants of Table 2 to predict their approximate frequencies. RFMWDR searches for selected transitions in the frequency region above 75 GHz soon met with success. A typical example of an RFMWDR identification is exemplified by the J = 2311 ← 2211 pair of transitions shown in Figure 3. CCSD dipole moment components are rather small (0.51 and 0.08 D, respectively), resulting in very weak transitions. Accurate values of the rotational and quartic centrifugal distortion constants have been obtained (Table 2). Attempts were made to include sextic centrifugal distortion constants in the least-squares fits, but the resulting constants had such large standard deviations that it was decided to limit the fits to include only quartic centrifugal distortion constants. The spectroscopic constants shown in Table 3 should predict the frequencies of rotational transitions that occur outside the investigated spectral interval (38−120 GHz) with a high degree of precision. The CCSD rotational constants of the three conformers (Table 2) have similar values with one exception, namely, the A rotational constant of II, which differs from the two other A constants by more than 100 MHz. The experimental effective (r0) A constant (Table 3) is much closer to the CCSD A constant of II than to the corresponding constants of I and III. It is therefore certain that the spectrum in Table S10 in the Supporting Information indeed belongs to II. The rotational constants of the deuterated species HCCCH(OD)CN discussed below confirm this assignment. The effective (r0) ground-state rotational constants (Table 3) are smaller than the CCSD constants (Table 2) by 16.7, 7.2, and 6.5 MHz in the cases of A, B, and C, respectively. The CCSD rotational constants are approximations of the equilibrium counterparts, which are usually found to be smaller than the effective constants since r0 values are normally longer than re values, resulting in larger principal moments of inertia and smaller values for the effective rotational constants. The MP2 method predicts these differences to be 14.0, 5.9, and 7.6 MHz (Table S2 in the Supporting Information), in fair agreement with the present findings. There is very good agreement between the experimental (Table 3) quartic centrifugal distortion constants and the MP2 equivalents (Table 2) with one exception, namely, d2, but this experimental parameter is the least accurate centrifugal distortion constant. Vibrationally Excited States. The RFMWDR spectrum revealed transitions belonging to several vibrationally excited states. The spectra of two of these were assigned in the same manner as discussed above for the ground-state spectrum. The spectroscopic constants are included in Table 3, and the spectra are found in Tables S11 and S12 in the Supporting Information. The vibration−rotation constants α57 found by subtraction of the excited-state rotational constants from their ground-state equivalents are αA = −9.302(88) MHz, αB = −9.5343(88) MHz, and αC = −0.401 MHz, which can be compared with the MP2 values −11.2, −8.7, and −0.2 MHz, respectively, calculated for the lowest bending vibration (Table S2 in the Supporting Information). Rough relative intensity measurements yielded 110(25) cm−1 for this vibration, compared with the anharmonic MP2 frequency of 127 cm−1 (Table S2). The values αA = −10.70(14) MHz, αB = 6.5467(98) MHz, and αC = −2.670 MHz were calculated in a similar manner from the entries in Table 3 for the other excited state. The corresponding MP2 parameters of the second-lowest bending fundamental are −16.0, 7.6, and −3.1 MHz, respectively. Relative intensity measurements yielded ca. 180 cm−1 for this vibration, in accord with an anharmonic fundamental of 195 cm−1 (Table S2). It is concluded that the MP2 calculations in Figure 3. RFMWDR spectrum of the J = 2311 ← 2211 pair of transitions. The RF was 5.85 MHz. The frequencies are 116237.69 and 116247.76 MHz for the 2311,13 ← 2211,12 and 2311,12 ← 2211,11 transitions, respectively. The intensity is in arbitrary units. The frequencies of transitions having values of the pseudo quantum number K−1 larger than about 10, which occur in this spectral region, could then be predicted rather precisely. These transitions appear as coalescing pairs with very rapid Stark effects, and this property was useful in obtaining a secure assignment. Further assignments were then gradually made. A total of 275 aR transitions (listed in Table S10 in the Supporting Information) were ultimately assigned and leastsquares-fitted to Watson’s Hamiltonian in the S-reduction Irrepresentation form58 employing Sørensen’s program Rotfit.63 The resulting spectroscopic constants are shown in Table 3. The maximum value of J is 24, and the maximum value of K−1 is 23. None of the transitions displayed a hyperfine structure due to quadrupole coupling of the 14N nucleus. Searches for band c-type lines were made, but none could be unambiguously assigned. This is not surprising because the corresponding 637 DOI: 10.1021/jp5112923 J. Phys. Chem. A 2015, 119, 634−640 Article The Journal of Physical Chemistry A Table 3. Spectroscopic Constantsa of Vibrational States of Conformer II of HCCCH(OH)CN and HCCCH(OD)CN parent Av (MHz) Bv (MHz) Cv (MHz) DJ (kHz) DJK (kHz) DK (kHz) d1 (kHz) d2 (kHz) rmsb Nc deuterated ground lowest bend second-lowest bend ground 5756.892(46) 2874.2429(40) 2031.8990(50) 1.4360(35) −7.358(16) 20.52(61) −0.5912(34) −0.0275(23) 1.296 275 5766.194(76) 2883.7772(78) 2032.300(10) 1.378(12) −6.957(56) 29.4(21) −0.6211(97) −0.0648(87) 1.338 142 5767.59(13) 2867.6962(98) 2034.569(12) 1.202(10) −4.606(43) 20.8(16) −0.708(13) 0.142(10) 1.570 138 5518.987(85) 2854.6171(83) 2011.548(11) 1.3811(81) −6.137(34) 20.5(11) −0.5563(77) −0.0274(45) 1.462 155 a S-reduction Ir representation.58 Uncertainties represent one standard deviation. The spectra are listed in Tables S10−S13 in the Supporting Information. bRoot-mean-square deviation, defined as rms2 = ∑[(νobs − νcalc)/u]2/(N − P), where νobs and νcalc are the observed and calculated frequencies, u is the uncertainty of the observed frequency, N is the number of transitions used in the least-squares fit, and P is the number of spectroscopic constants used in the fit. cNumber of transitions used in the fit. and the π-electron systems of the triple bonds. There are three polar groups in HBN that may interact. The most polar of them is the cyano group, which has a bond dipole moment as large as 3.6 D66 with nitrogen as the negative end. The bond dipole moment of the hydroxyl group is 1.5 D,66 while propyne (CH3CCH) has a dipole moment of 0.7804 D with CH as the negative end.67 In conformer I, the CCSD angle between the C1N6 and O8−H9 bonds is 67.8° (from Cartesian coordinates in Table S7 in the Supporting Information). The two groups are oriented in such a manner that dipole−dipole stabilization should be significant. The O8−H9 and C3C4 bonds are 3° from being parallel, while the associated bond dipole moments are antiparallel, resulting in a minor repulsion. The nonbonded distances between the H9 atom and the C1 and N6 atoms are 256 and 340 pm, respectively (Table S7), which can be compared to the sum of the Pauling van der Waals radius68 of hydrogen (120 pm) and the half-thickness of an aromatic molecule (170 pm), which is 290 pm. This suggests that the covalent stabilization between H9 and the π electrons of the C1N6 bond is not a large effect. Conformer III resembles I. The bond dipole moments of the O8−H9 and C3C4 groups stabilize III in this case, while the electrostatic interaction caused by the O8−H9 and C1N6 groups destabilizes III. The nonbonded distance between H9 and C3 is 240 pm and the distance between H9 and C4 is 334 pm, resulting in a weak covalent stabilization. In conformer II, the electrostatic interactions between the O8−H9 group and both the C1N6 and C3C4 groups are similar to those found in I and III, respectively. The covalent stabilization with the π electrons of the two groups is also similar. The much better situation for both electrostatic and covalent contributions to the hydrogen bonding in II makes this conformer several kJ/mol lower in energy than I and III, in agreement with the present experimental findings. this case were able to predict the correct sign and order of magnitude for the α constants. Deuterated Species. The spectrum of the deuterated species HCCCH(OD)CN, which was assigned in a straightforward manner, is listed in Table S13 in the Supporting Information, and the spectroscopic constants are displayed in Table 3. The substitution coordinates64 of the hydrogen atom of the hydroxyl group in the principal axis system were calculated from the rotational constants of the parent and deuterated species (Table 3) using Kraitchman’s equations65 and were found to be |b| = 158.651(51) pm and |c| = 113.542(51) pm, while the a coordinate has a small imaginary value. The uncertainties (one standard deviation) were calculated from the standard deviations of the rotational constants. The CCSD values of these coordinates are |a| = 8.39 pm, |b| = 157.52 pm, and |c| = 113.89 pm (Table S8 in the Supporting Information), in good agreement with the substitution coordinates above. The corresponding CCSD values for conformer I are |a| = 78.85 pm, |b| = 213.39 pm, and |c| = 1.39 pm (Table S7 in the Supporting Information), while the values for III are |a| = 77.17 pm, |b| = 208.89 pm, and |c| = 16.54 pm (Table S9 in the Supporting Information). The substitution coordinates of the hydroxyl group again show conclusively that the assigned spectra belong to II and that confusion with I or III is out of the question. Searches for the Spectra of I and III. Conformer III has a dipole moment component along the a principal inertial axis as large as 4.4 D according to the CCSD method (Table 2). Searches were performed for selected aR transitions of this rotamer using the RFMWDR technique, but no characteristic double-resonance signals were observed. This is taken as an indication that there is a substantial energy difference between III and II, producing insufficient intensities for the spectrum of III. This is in accord with the MP2 and CCSD calculations, which predict an energy difference of about 6 kJ/mol. Searches for I were also negative. This form is also significantly higher in energy than II as discussed above. ■ ■ ASSOCIATED CONTENT S Supporting Information * DISCUSSION Several intramolecular forces appear to determine the conformational properties of HBN. Internal hydrogen bonding is present in all three forms. The hydrogen bonds are composed primarily of two types of interactions, namely, dipole−dipole interactions and covalent interactions between the H9 atom Results of the theoretical calculations, including electronic energies, molecular structures, dipole moments, harmonic and anharmonic vibrational frequencies, rotational and centrifugal distortion constants, and rotation-vibration constants, and microwave spectra of the ground and vibrationally excited states of the parent species and the ground state of the 638 DOI: 10.1021/jp5112923 J. Phys. Chem. A 2015, 119, 634−640 Article The Journal of Physical Chemistry A troscopy and Quantum Chemical Calculations. J. Phys. Chem. A 2006, 110, 6054−6059. (14) Møllendal, H.; Samdal, S. Conformation and Intramolecular Hydrogen Bonding of 2-Chloroacetamide As Studied by Microwave Spectroscopy and Quantum Chemical Calculations. J. Phys. Chem. A 2006, 110, 2139−2146. (15) Cole, G. C.; Møllendal, H.; Guillemin, J.-C. Spectroscopic and Quantum Chemical Study of the Novel Compound Cyclopropylmethylselenol. J. Phys. Chem. A 2006, 110, 2134−2138. (16) Møllendal, H. Recent Gas-Phase Studies of Intramolecular Hydrogen Bonding. NATO ASI Ser., Ser. C 1993, 410, 277−301. (17) Wilson, E. B.; Smith, Z. Intramolecular Hydrogen Bonding in Some Small Vapor-Phase Molecules Studied with Microwave Spectroscopy. Acc. Chem. Res. 1987, 20, 257−262. (18) Smith, G.; Glaser, M.; Perumal, M.; Nguyen, Q.-D.; Shan, B.; Årstad, E.; Aboagye, E. O. Design, Synthesis, and Biological Characterization of a Caspase 3/7 Selective Isatin Labeled with 2[18F]fluoroethylazide. J. Med. Chem. 2008, 51, 8057−8067. (19) Kovacs, A.; Szabo, A.; Hargittai, I. Structural Characteristics of Intramolecular Hydrogen Bonding in Benzene Derivatives. Acc. Chem. Res. 2002, 35, 887−894. (20) Desiraju, G.; Steiner, T. The Weak Hydrogen Bond: Applications to Structural Chemistry and Biology; Oxford University Press: Oxford, U.K., 1999. (21) Marstokk, K.-M.; Møllendal, H. Microwave Spectrum, Conformational Equilibria, Intramolecular Hydrogen Bonding, Dipole Moment and Centrifugal Distortion of 3-Hydroxypropanenitrile. Acta Chem. Scand., Ser. A 1985, A39, 15−31. (22) Cazzoli, G.; Lister, D. G.; Mirri, A. M. Rotational Isomerism and Barriers to Internal Rotation in Hydroxyacetonitrile from Microwave Spectroscopy. J. Chem. Soc., Faraday Trans. 2 1973, 69, 569−578. (23) Caminati, W.; Meyer, R.; Oldani, M.; Scappini, F. Microwave Investigation of Lactonitrile. Potential Functions to the Hydroxyl and Methyl Group Torsions. J. Chem. Phys. 1985, 83, 3729−3737. (24) Corbelli, G.; Lister, D. G. The Microwave Spectrum of Acetaldehyde Cyanohydrin. J. Mol. Struct. 1981, 74, 39−42. (25) Lister, D. G.; Lowe, S. E. The Conformation of Acetone Cyanohydrin by Microwave Spectroscopy. J. Mol. Struct. 1977, 41, 318−320. (26) Hirota, E. Internal Rotation in Propargyl Alcohol from Microwave Spectrum. J. Mol. Spectrosc. 1968, 26, 335−350. (27) Marstokk, K.-M.; Møllendal, H. Microwave Spectrum, Conformational Equilibrium, Intramolecular Hydrogen Bonding, Dipole Moments and Centrifugal Distortion Constants of 3-Butyn-2ol. Acta Chem. Scand., Ser. A 1985, A39, 639−649. (28) Szalanski, L. B.; Ford, R. G. Microwave Spectrum of 3-Butyn-1ol. J. Mol. Spectrosc. 1975, 54, 148−155. (29) Slagle, E. D.; Peebles, R. A.; Peebles, S. A. An ab Initio Investigation of Five Conformers of 3-Butyn-1-ol and the Structure of the Most Stable Species from Microwave Spectroscopy. J. Mol. Struct. 2004, 693, 167−174. (30) Holt, J.; Hanefeld, U. Enantioselective Enzyme-Catalysed Synthesis of Cyanohydrins. Curr. Org. Synth. 2009, 6, 15−37. (31) Dadashipour, M.; Asano, Y. Hydroxynitrile Lyases: Insights into Biochemistry, Discovery, and Engineering. ACS Catal. 2011, 1, 1121− 1149. (32) North, M.; Usanov, D. L.; Young, C. Lewis Acid Catalyzed Asymmetric Cyanohydrin Synthesis. Chem. Rev. 2008, 108, 5146− 5226. (33) Danger, G.; Duvernay, F.; Theulé, P.; Borget, F.; Chiavassa, T. Hydroxyacetonitrile (HOCH2CN) Formation in Astrophysical Conditions. Competition with the Aminomethanol, a Glycine Precursor. Astrophys. J. 2012, 756, No. 11. (34) Irvine, W. M.; Brown, R. D.; Cragg, D. M.; Friberg, P.; Godfrey, P. D.; Kaifu, N.; Matthews, H. E.; Ohishi, M.; Suzuki, H.; Takeo, H. A New Interstellar Polyatomic Molecule: Detection of Propynal in the Cold Cloud TMC-1. Astrophys. J. 1988, 335, L89−L93. deuterated species. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org. ■ AUTHOR INFORMATION Corresponding Author *Tel: +47 2285 5674. Fax: +47 2285 5441. E-mail: harald. mollendal@kjemi.uio.no. Notes The authors declare no competing financial interest. ■ ACKNOWLEDGMENTS We thank Anne Horn for her skillful assistance. This work was supported by the Research Council of Norway through a Centre of Excellence Grant (Grant 179568/V30) and by the Norwegian Supercomputing Program (NOTUR) through a grant of computer time (Grant NN4654K).). J.-C.G. thanks the French National Program Physique et Chimie du Milieu Interstellaire (PCMI (INSU-CNRS)) and the Centre National d’Etudes Spatiales (CNES) for grants. ■ REFERENCES (1) Møllendal, H.; Samdal, S.; Guillemin, J.-C. Microwave Spectrum and Intramolecular Hydrogen Bonding of 2-Isocyanoethanol (HOCH2CH2NC). J. Phys. Chem. A 2014, 118, 3120−3127. (2) Møllendal, H.; Margules, L.; Belloche, A.; Motiyenko, R. A.; Konovalov, A.; Menten, K. M.; Guillemin, J. C. Rotational Spectrum of a Chiral Amino Acid Precursor, 2-Aminopropionitrile, And Searches for It in Sagittarius B2(N). Astron. Astrophys. 2012, 538, No. A51. (3) Møllendal, H.; Samdal, S.; Guillemin, J.-C. Microwave Spectrum, Conformational Composition, and Intramolecular Hydrogen Bonding of (2-Chloroethyl)amine (ClCH2CH2NH2). J. Phys. Chem. A 2011, 115, 4334−4341. (4) Møllendal, H.; Konovalov, A.; Guillemin, J.-C. Microwave Spectrum and Conformational Composition of (Chloromethyl)phosphine (ClCH2PH2). J. Phys. Chem. A 2010, 114, 10612−10618. (5) Møllendal, H.; Konovalov, A.; Guillemin, J.-C. Microwave Spectrum and Intramolecular Hydrogen Bonding of Propargyl Selenol (HCCCH2SeH). J. Phys. Chem. A 2010, 114, 5537−5543. (6) Møllendal, H.; Konovalov, A.; Guillemin, J.-C. Microwave Spectrum and Intramolecular Hydrogen Bonding of 2-Propene-1selenol (H2CCHCH2SeH). J. Phys. Chem. A 2009, 113, 6342−6347. (7) Møllendal, H. Microwave Spectrum, Conformation, and Intramolecular Hydrogen Bonding of 2,2,2-Trifluoroethanethiol (CF3CH2SH). J. Phys. Chem. A 2008, 112, 7481−7487. (8) Møllendal, H.; Mokso, R.; Guillemin, J.-C. A Microwave Spectroscopic and Quantum Chemical Study of 3-Butyne-1-selenol (HSeCH2CH2CCH). J. Phys. Chem. A 2008, 112, 3053−3060. (9) Møllendal, H.; Dreizler, H.; Sutter, D. H. Structural and Conformational Properties of 4-Pentyn-1-ol As Studied by Microwave Spectroscopy and Quantum Chemical Calculations. J. Phys. Chem. A 2007, 111, 11801−11808. (10) Cole, G. C.; Møllendal, H.; Khater, B.; Guillemin, J.-C. Synthesis and Characterization of (E)- and (Z)-3-Mercapto-2-propenenitrile. Microwave Spectrum of the Z-Isomer. J. Phys. Chem. A 2007, 111, 1259−1264. (11) Askeland, E.; Møllendal, H.; Uggerud, E.; Guillemin, J.-C.; Aviles Moreno, J.-R.; Demaison, J.; Huet, T. R. Microwave Spectrum, Structure, and Quantum Chemical Studies of a Compound of Potential Astrochemical and Astrobiological Interest: (Z)-3-Amino-2propenenitrile. J. Phys. Chem. A 2006, 110, 12572−12584. (12) Cole, G. C.; Møllendal, H.; Guillemin, J.-C. Microwave Spectrum of 3-Butyne-1-thiol: Evidence for Intramolecular S−H···π Hydrogen Bonding. J. Phys. Chem. A 2006, 110, 9370−9376. (13) Møllendal, H.; Frank, D.; de Meijere, A. Structural and Conformational Properties and Intramolecular Hydrogen Bonding of (Methylenecyclopropyl)methanol, As Studied by Microwave Spec639 DOI: 10.1021/jp5112923 J. Phys. Chem. A 2015, 119, 634−640 Article The Journal of Physical Chemistry A (35) Hollis, J. M.; Jewell, P. R.; Lovas, F. J.; Remijan, A.; Møllendal, H. Green Bank Telescope Detection of New Interstellar Aldehydes. Propenal and Propanal. Astrophys. J. 2004, 610, L21−L24. (36) Requena-Torres, M. A.; Martin-Pintado, J.; Martin, S.; Morris, M. R. The Galactic Center: The Largest Oxygen-Bearing Organic Molecule Repository. Astrophys. J. 2008, 672, 352−360. (37) Snyder, L. E.; Buhl, D. Radio Emission from Interstellar Hydrogen Cyanide. Astrophys. J. 1971, 163, L47−L52. (38) Rambaud, R.; Vessiere, R.; Verny, M. Derivatives of 2-Hydroxy3-Butynoic and 2-Chloro-3-Butynoic Acids. C. R. Hebd. Seances Acad. Sci. 1963, 257, 1619−1621. (39) Wirsching, P.; O’Leary, M. H. 1-Carboxyallenyl Phosphate, an Allenic Analog of Phosphoenolpyruvate. Biochemistry 1988, 27, 1355− 1360. (40) Sauer, J. C. Propiolaldehyde. Org. Synth. 1956, 36, 66−69. (41) Sauer, J. C. Propiolaldehyde. Organic Syntheses; Wiley and Sons: New York, 1963; Collect. Vol. IV, 813. (42) Costain, C. C.; Morton, J. R. Microwave Spectrum and Structure of Propynal (HCCCHO). J. Chem. Phys. 1959, 31, 389−393. (43) Winnewisser, G. Ground State of Propynal. J. Mol. Spectrosc. 1973, 46, 16−24. (44) Jaman, A. I.; Bhattacharya, R.; Mandal, D.; Das, A. K. Millimeterwave Spectral Studies of Propynal (HCCCHO) Produced by DC Glow Discharge and ab Initio DFT Calculation. J. At., Mol., Opt. Phys. 2011, No. 439019. (45) Nethercot, A. H., Jr.; Klein, J. A.; Townes, C. H. The Microwave Spectrum and Molecular Constants of Hydrogen Cyanide. Phys. Rev. 1952, 86, 798−799. (46) Gordy, W. Microwave Spectroscopy above 60 KMc. Ann. N.Y. Acad. Sci. 1952, 55, 774−788. (47) Samdal, S.; Grønås, T.; Møllendal, H.; Guillemin, J.-C. Microwave Spectrum and Conformational Properties of 4-Isocyano1-butene (H2CCHCH2CH2NC). J. Phys. Chem. A 2014, 118, 1413−1419. (48) Wodarczyk, F. J.; Wilson, E. B., Jr. Radio Frequency-Microwave Double Resonance as a Tool in the Analysis of Microwave Spectra. J. Mol. Spectrosc. 1971, 37, 445−463. (49) Møller, C.; Plesset, M. S. Note on the Approximation Treatment for Many-Electron Systems. Phys. Rev. 1934, 46, 618−622. (50) Cizek, J. Use of the Cluster Expansion and the Technique of Diagrams in Calculations of Correlation Effects in Atoms and Molecules. Adv. Chem. Phys. 1969, 14, 35−89. (51) Purvis, G. D., III; Bartlett, R. J. A Full Coupled-Cluster Singles and Doubles Model: The Inclusion of Disconnected Triples. J. Chem. Phys. 1982, 76, 1910−1918. (52) Scuseria, G. E.; Janssen, C. L.; Schaefer, H. F., III. An Efficient Reformulation of the Closed-Shell Coupled Cluster Single and Double Excitation (CCSD) Equations. J. Chem. Phys. 1988, 89, 7382−7387. (53) Scuseria, G. E.; Schaefer, H. F., III. Is Coupled Cluster Singles and Doubles (CCSD) More Computationally Intensive Than Quadratic Configuration Interaction (QCISD)? J. Chem. Phys. 1989, 90, 3700−3703. (54) Frisch, M. J.; Trucks, G. W.; Schlegel, H. B.; Scuseria, G. E.; Robb, M. A.; Cheeseman, J. R.; Scalmani, G.; Barone, V.; Mennucci, B.; Petersson, G. A.; et al. Gaussian 09, revision B.01; Gaussian, Inc: Wallingford, CT, 2009. (55) Werner, H.-J.; Knowles, P. J.; Knizia, G.; Manby, F. R.; Schütz, M.; et al. MOLPRO: A Package of Ab Initio Programs, version 2010.1; http://www.molpro.net/. (56) Peterson, K. A.; Dunning, T. H., Jr. Accurate Correlation Consistent Basis Sets for Molecular Core−Valence Correlation Effects: The Second Row Atoms Al−Ar, and the First Row Atoms B−Ne Revisited. J. Chem. Phys. 2002, 117, 10548−10560. (57) Gordy, W.; Cook, R. L. Microwave Molecular Spectra; Techniques of Chemistry, Vol. XVII; John Wiley & Sons: New York, 1984. (58) Watson, J. K. G.: Vibrational Spectra and Structure; Elsevier: Amsterdam, 1977; Vol. 6. (59) McKean, D. C.; Craig, N. C.; Law, M. M. Scaled Quantum Chemical Force Fields for 1,1-Difluorocyclopropane and the Influence of Vibrational Anharmonicity. J. Phys. Chem. A 2008, 112, 6760−6771. (60) Koput, J. The Equilibrium Structure and Torsional Potential Energy Function of Methanol and Silanol. J. Phys. Chem. A 2000, 104, 10017−10022. (61) Puzzarini, C.; Cazzoli, G. Equilibrium Structure of Methylcyanide. J. Mol. Spectrosc. 2006, 240, 260−264. (62) Lievin, J.; Demaison, J.; Herman, M.; Fayt, A.; Puzzarini, C. Comparison of the Experimental, Semi-Experimental and Ab Initio Equilibrium Structures of Acetylene: Influence of Relativisitic Effects and of the Diagonal Born−Oppenheimer Corrections. J. Chem. Phys. 2011, 134, No. 064119. (63) Sørensen, G. O. Centrifugal Distortion Analysis of Microwave Spectra of Asymmetric Top Molecules. The Microwave Spectrum of Pyridine. J. Mol. Spectrosc. 1967, 22, 325−346. (64) Costain, C. C. Determination of Molecular Structures from Ground-State Rotational Constants. J. Chem. Phys. 1958, 29, 864−874. (65) Kraitchman, J. Determination of Molecular Structure from Microwave Spectroscopic Data. Am. J. Phys. 1953, 21, 17−24. (66) Exner, O. Dipole Moments in Organic Chemistry; Thieme: Stuttgart, Germany, 1975. (67) Muenter, J. S.; Laurie, V. W. Deuterium Isotope Effects on Molecular Dipole Moments by Microwave Spectroscopy. J. Chem. Phys. 1966, 45, 855−858. (68) Pauling, L.: The Nature of the Chemical Bond; Cornell University Press: Ithaca, NY, 1960. 640 DOI: 10.1021/jp5112923 J. Phys. Chem. A 2015, 119, 634−640