The mating system of polar bears: a genetic approach

advertisement

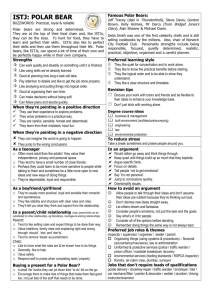

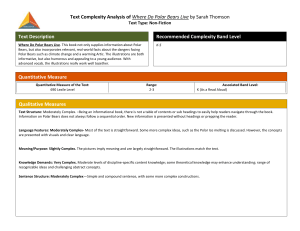

1195 The mating system of polar bears: a genetic approach E. Zeyl, J. Aars, D. Ehrich, L. Bachmann, and Ø. Wiig Abstract: Parentage analysis data for 583 individuals genotyped at 27 microsatellite loci were used to study the mating system of polar bears (Ursus maritimus Phipps, 1774) in the Barents Sea area. We discriminated statistically between full and half-siblings identified through only one common parent. We document for the first time multiple paternity in polar bears. We demonstrated for both sexes low fidelity to mating partners over time. We did not detect any significant difference between the age distribution of adult males at capture and the age distribution of males siring cubs. This might indicate that the male’s age and size are less indicative of the reproductive success than previously thought. This is further supported by a rather long mean litter interval of 3.9 years for males siring several litters. The mating system of polar bears in the Barents Sea appears to be promiscuous, usually with a single successful father siring full siblings within a year, but with consecutive litters of a mother being fathered by different males. We discuss how population density, landscape characteristics, and adult sex ratio might influence the mating system of polar bears. This is of particular importance for management decisions such as, e.g., implementing sex ratios in hunting quotas. Résumé : Nous utilisons les résultats d’analyses de filiation portant sur 583 individus génotypés à 27 loci microsatellites, afin d’étudier le système de reproduction des ours blancs (Ursus maritimus Phipps, 1774) de la région de la Mer de Barents. Nous avons statistiquement discriminé entre les vrais-frères et sœurs et les demi-frères et sœurs identifiés par un seul parent commun. Nous documentons, pour la première fois chez les ours blancs, un cas de parenté multiple dans une même portée. Nous avons démontré une faible fidélité entre partenaires sexuels, lors de différentes reproductions, quel que soit le sexe. Nous n’avons pas détecté de différence entre la distribution des âges des mâles adultes à la capture et la distribution des âges des mâles au moment où ils sont pères. Cela pourrait indiquer que l’âge des mâles et leur taille sont une moindre indication du succès de leur reproduction qu’on ne le croyait. Cela est supporté par un intervalle moyen assez long (3,9 ans) entre les portées pour les pères ayant engendré plusieurs portées. Nos résultats indiquent que le système de reproduction des ours blancs de la mer de Barents semble lié à la promiscuité; ainsi, de manière générale, un mâle est le père de tous les petits d’une portée, mais les portées successives d’une femelle ont des pères différents. Nous discutons comment les variations de densité des populations et des caractéristiques du paysage, ainsi que le rapport des sexes des adultes peuvent influencer le système de reproduction des ours blancs. Ceci est important pour les décisions de gestion des populations, par ex. la fixation du rapport des sexes dans les quotas de chasse. Introduction Information about the mating system and the reproductive biology of both sexes is important for wildlife conservation and management. Mating systems can be viewed as different degrees of female monopolization by males (Le Boeuf 1991). In species where males do not contribute to parental care the main factor influencing the ability of males to monopolize receptive females, and hence the male reproductive success, is the temporal distribution of receptive females. The operational sex ratio (i.e., number of adult males per receptive female; OSR) and female spatial distribution are important factors when there is little estrous synchronization (Ims 1988). In general, the spatial distribution of females is Received 21 April 2009. Accepted 3 September 2009. Published on the NRC Research Press Web site at cjz.nrc.ca on 4 December 2009. E. Zeyl,1 L. Bachmann, and Ø. Wiig. Natural History Museum, National Centre for Biosystematics, University of Oslo, P.O. Box 1172 Blindern, NO-0318 Oslo, Norway. J. Aars. Norwegian Polar Institute, NO-9296 Tromsø, Norway. D. Ehrich. University of Tromsø, Department of Biology, NO-9037 Tromsø, Norway. 1Corresponding author (e-mail: eve.zeyl@nhm.uio.no). Can. J. Zool. 87: 1195–1209 (2009) closely associated with resources necessary for producing and rearing the young (Davies and Lundberg 1984; Gehrt and Fritzell 1998). Among marine mammals such as pinnipeds, the spatial and temporal distribution of females determine the mating system in that the degree of polygyny (where males mate with the same restricted group of females in successive mating attempts; Clutton-Brock 1989) varies with female clumping and estrous synchrony (Boness 1991). In land-breeding pinnipeds such as northern elephant seals (Mirounga angustirostris (Gill, 1866)), the females are spatially clumped. Accordingly, the mating system is highly polygynous and the variance of lifetime reproductive success is estimated to be four times greater among males than females (Le Boeuf and Reiter 1988; Le Boeuf 1991). The mating systems of ice-breeding seals with spatially scattered distribution of females are less well known (Le Boeuf 1991). Promiscuity such as in harp seals (Pagophilus groenlandicus (Erxleben, 1777); Kovacs 1995 in Kovacs et al. 1997) and slight polygyny or serial monogamy (where females (or males) usually mate with a single partner in successive breeding attempts during a single breeding season but mate with several different partners during their lifetime; Clutton-Brock 1989) such as in hooded seals (Cystophora cristata (Erxleben, 1777); Boness et al. 1988; McRae and Kovacs 1994) has been reported. doi:10.1139/Z09-107 Published by NRC Research Press 1196 In many species, females may mate with several males during a mating season (polyandry, where females mate with the same restricted group of males in successive breeding attempts; Clutton-Brock 1989). In mammals, various benefits have been hypothesized for such behavior, e.g., improvement of fecundity by confusing paternity and thus reduction of the risk of infanticide from the mating males (Hosken and Stockley 2003), or avoidance of inbreeding (Stockley et al. 1993). In pinnipeds, the multiple copulations by females have been interpreted as an avoidance strategy toward male harassment in periods when females are spatially clumped (Cassini 1999). Mating with more than one male during an oestrus may result in multiple paternity within a litter. Multiple paternity is common in mammals (Baker et al. 1999; Burton 2002; DeYoung et al. 2002; Crawford et al. 2008) and has also been documented in several bear species, such as in American black bears (Ursus americanus Pallas, 1780; (Schenk and Kovacs 1995; Sinclair et al. 2003). In Swedish brown bears (Ursus arctos L., 1758), a minimum of 10 out of 69 litters (14.5%) were fathered by several males (Bellemain et al. 2006a). However, the frequency of multiple paternity may vary between (Baker et al. 1999; Burton 2002) and within species, and may depend on population density (Say et al. 1999). Multiple paternity is expected to be more common in species with synchronized oestrus and spatially clustered receptive females, making it more difficult for males to monopolize individual receptive females (Clutton-Brock 1989; Isvaran and Clutton-Brock 2007). Polar bears (Ursus maritimus Phipps, 1774) are solitary marine carnivores. Their breeding season extends from March to May (Lønø 1970; Tumanov 2001; Rosing-Asvid et al. 2002). Most ovulations are believed to occur in April and May (Rosing-Asvid et al. 2002) and the oestrus is thus not synchronous. Female polar bears enter oestrus every 2 or 3 years after weaning off their offspring (Ramsay and Stirling 1986; Derocher and Stirling 1998), or after they have lost their offspring before weaning (Ramsay and Stirling 1986). Polar bears live in a highly unstable environment; sea-ice extent and characteristics are constantly changing under the influence of temperature, wind, and sea currents (Ferguson et al. 1998). Females in oestrus are not particularly clustered, but their distribution is considered to be determined by foraging opportunities. Males may be distributed with the same relative densities as solitary females (Ramsay and Stirling 1986). The mating success of female polar bears may depend both on the OSR and on the density of available breeding males (Molnár et al. 2008). In an area such as the Barents Sea with moderate or high densities of polar bears and where hunting is prohibited (Aars et al. 2009), it is unlikely that lack of opportunity to find a male partner restricts female reproduction. Depending on social and ecological conditions, the timing of first reproduction might be delayed well beyond sexual maturity (Say et al. 1999). Male polar bears attain 97% of their asymptotic body mass at approximately 13 years of age (Derocher et al. 2005). Although age of maturity is about 5 years, it is expected that middle-aged males will have preferential access to females owing to increased competitiveness (Bunnell and Tait 1981; Ramsay and Stirling 1986). In addition, most polar bear populations are harvested Can. J. Zool. Vol. 87, 2009 by indigenous people, and harvest is usually male-biased (Derocher et al. 1997). Removal of problem bears is also typically male-biased (Dyck 2006). In a long-term perspective, this could result in a lack of sexually mature males in the population, which could impair fecundity (McLoughlin et al. 2005; Taylor et al. 2008). Knowing how reproductive success of males varies with age would prove valuable to population dynamics modelling and management. In the present study, we use genetic and parentage data from the Barents Sea to gain information about the mating system of polar bears, which is currently known only from behavioral observations (Ramsay and Stirling 1986; Wiig et al. 1992; Rosing-Asvid et al. 2002). First, we assess evidence for multiple paternity. Traditional methods to detect multiple paternity require either that both parents are identified or that incompatible alleles are assessed within litters consisting of at least three siblings (Burton 2002; Bellemain et al. 2006a; Crawford et al. 2008). Here, two statistical likelihood approaches were applied in addition to the traditional method (Bellemain et al. 2006a) to discriminate between half-siblings (HS) and full siblings (FS) within litters. These methods were employed to discriminate between HS and FS identified by at least one common parent (father or mother) assigned through parentage analysis. Considering the male-biased OSR in the Barents Sea population and earlier observations of females consorting successively with several males (Wiig et al. 1992), we expect multiple paternity to occur. However, taking into account the long breeding period and the unpredictability of the spatial distribution of females during the mating season owing to large temporal changes in distribution of sea ice, multiple paternity may also be relatively rare. Second, we investigate to which degree polar bears breed with the same mate in different years. We also estimate the time span between litters sired by the same male. Intense wounding and scaring (Ramsay and Stirling 1986) of males during the breeding season certainly indicates high male competition for mating opportunities. Young males are hypothesized to have lesser competitive abilities than older males (Ramsay and Stirling 1986) and to be less attractive for females (Derocher et al. 2005). We consequently expect low fidelity between mating partners and a short time span between litters sired by reproductively succesful males. Furthermore, we expect a propensity of males siring litters to be older than the mean age of adult males at capture. Finally, we compare the accuracy of the different methods employed for discriminating between HS and FS relationships. Materials and methods Study area, animal sampling, laboratory procedures, and parentage analysis The Barents Sea population of polar bears has been defined as the animals occupying the area between longitudes of 108E and 608E, and latitudes of 728N and 838N (Wiig and Derocher 1999); an area that belongs to Norway and Russia. The population has been protected from harvesting since 1973 (Prestrud and Strirling 1994). The mean density of polar bears in the Barents Sea area is moderate to high (1.1 bear per 100 km2 in August 2004) compared with mean densities reported in several other surveyed areas, but Published by NRC Research Press Zeyl et al. local density varies considerably (Aars et al. 2009). The present study is based on animals captured during spring in the years 1995–2006. A detailed description of the study area and the sampling procedure was provided elsewhere (Wiig 1995; Zeyl et al. 2009). The animal-handling methods used had previously been granted approval by the Norwegian Animal Health Authority (Oslo, Norway). The laboratory methods and basic population genetics analysis tools used in this study have been previously described (Zeyl et al. 2009). In brief, DNA was isolated from tissue samples following a standard chloroform–phenol protocol for 151 samples (Sambrook and Russell 2001) or the manufacturer’s instructions of the DNeasy tissue kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) for 432 samples. Twenty-seven bear-specific polymorphic microsatellite loci (Crompton et al. 2008) were amplified in six multiplex polymerase chain reactions for 583 samples and 126 blind replicates, i.e., 21% of the samples. The mean error rate per locus was 0.004 (range = 0–0.045) for allelic dropout (ADO) and 0.005 (range = 0–0.023) for false alleles. Two of 89 mother–offspring pairs identified by field observations showed one incompatibility each, which is likely to result from the mistyping of adjacent alleles corresponding to an estimated error rate of 8.3 10–5 per locus. Evidence for significant scoring errors was not found when comparing the consensus of 126 samples with the consensus of the 126 blind replicates. The mean number of alleles per locus estimated using GENALEX version 6 (Peakall and Smouse 2006) was 8.04 (SD = 3.07, range = 2–15), the mean observed heterozygosity was 0.61 (SD = 0.24, range = 0.02–0.85), and the mean expected heterozygosity was 0.62 (SD = 0.24, range = 0.02–0.85). The level of resolution was high with an estimated probability of identity of 6.74 10–23, following Paetkau and Strobeck (1994). The probability of identity among siblings, accounting for the presence of relatives in the data set, remained low (1.92 10–9), following Waits et al. (2001). No individuals shared identical genotypes. Deviations from Hardy–Weinberg and linkage equilibriums were tested for each locus using the GENEPOP version 3.4 software (Raymond and Rousset 1995). No deviation from Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium was observed for the adult individuals (FIS = 0.003, p = 0.0798). There was no indication that loci were physically linked (Zeyl et al. 2009). We herein use the results of DNA-based parentage analyses from 583 individuals (309 females, 271 males, and 3 mislabeled samples for which the reference number did not correspond to any individual in the field data; Zeyl et al. 2009), performed using the software Parente (Cercueil et al. 2002). To avoid the incorrect rejection of parentages, a maximum of three incompatibilities between parent–offspring pairs was accepted. Even in the case of a low mean error rate of only 1% over all loci up to 40.7% of erroneous genotypes can be expected, following Bonin et al. (2004). Parentage was assigned when the probability of being the true parent was >0.5, a rather conservative cutoff value. In addition, two mother–offspring relationships were assigned because the mothers had been captured together with the cubs. The respective probabilities of being the true mother in these cases were low (0.2404 and 0.4802), but no genotype incompatibility was observed. In all other cases of parentage assigned with only low probability, we noted that several 1197 relatives of the parent–offspring pairs were included in the data set, which might explain the low probabilities for assigning the true parent (Jones and Ardren 2003; Morrissey and Wilson 2005). The mean probability of being the true parent for assigned parentage was high (0.97 for mother–offspring and 0.96 for father–offspring). Relatedness between individuals was computed using ML-Relate (Kalinowski et al. 2006) on all genotyped individuals (n = 583). Allele frequencies were estimated with the software ML-Relate from 412 bears captured as adults, as these should represent the reproductive part of the population. Discriminating between full siblings and half-siblings Directly assessing incompatible alleles within groups of offspring (the traditional method) allows identifying HS only in cases where three or more siblings were assigned to a common parent (parent 1). If, in addition to the two alleles from parent 1, three or more alleles were detected, this was taken as an indication that the siblings were born from at least two different parents of the sex opposite to that of the parent 1 (i.e., that at least one of them was a HS). If no more than two additional alleles were detected, this would, however, not prove that the siblings were FS. Thus, the traditional method provides a minimum estimate of the number of HS. We report the results of this method only for comparison with two other statistical methods that can be applied to the entire data set. The second method uses maximum-likelihood estimates of relatedness and performs a statistical test based on simulated genotypes to assess the significance of the likelihood ratio (LR) between the most likely relationship and an alternative relationship (Kalinowski et al. 2006). The pairwise relationship tests are implemented in the software MLRelate (Kalinowski et al. 2006). For each pair of siblings we tested either FS against HS or HS against FS, depending on which relationship had the highest likelihood. The p value of each hypothesis was computed using 100 000 simulated genotypes. If the p value was £0.05, we accepted the relationship with the highest likelihood; otherwise we considered the relationship as uncertain. The third method uses also LRs to compare the evidence for two alternative relationship hypotheses (Mayor and Balding 2006). It differs from the ML-Relate method by taking into account the genotype of the assigned parent when computing likelihoods. Analysis were run in R version 2.8.0 (R Development Core Team 2008). Mayor and Balding (2006) showed that if the maternal genotype is known, only 22–24 loci are required to obtain misclassification rates below 2%, applying a decision rule based on LRs larger or smaller than 1. We used a somewhat more stringent decision rule, as our objective was to minimize the risk of erroneously accepting a HS relation when a FS relation is true. Thus, individuals were considered FS when LRs were ‡2, and HS when LRs were £0.5. Between those values, the relationship was considered uncertain. In case of incongruent outcomes between the methods, we accepted the results from Mayor’s method (method 3), as it was considered more powerful (see comparison between the methods below). Rejecting the FS hypothesis for siblings from a litter implies multiple paternity. Rejection of the HS hypothesis for Published by NRC Research Press 1198 siblings from different litters suggests that the mother had mated successfully with the same male in different years. Siblings were only attributed to the same litter when they had been captured as dependent young with their mother. When offspring were not captured as dependent young with their mother, their estimated year of birth is uncertain (see below). In such cases, assigning siblings as FS could indicate either that the siblings originated from a single litter or that repeated mating between the same partners occurred in different years. None of the used methods accommodates for genotyping errors. Thus loci, at which offspring showed incompatibility with their assigned parent owing to erroneous genotyping (such as, e.g., allelic dropout), were removed from the analysis. Removed loci were UarMU50, G10C–UarMU61, G10B, LIST11016–G10B, LIST11020, and G10C for individuals O6, O30, O33, O65, O77, and O79, respectively, in Table 1. Removed loci were G10D–G10P–G10B, LIST11020– G10P, and LIST11020 for individuals O100, O105, and O107, respectively, in Table 2. Missing loci owing to amplification failure were also excluded from the analysis with Mayor’s method, as it does not allow for missing information. Excluded loci were UarMU61 for individual M36 in Table 1 and UarMU50, G10D, UarMU10, and MSUT3– G10H for individuals O28, F16, O119, and O120, respectively, in Table 2. Both likelihood methods assume that neither of the two individuals being compared are inbred. This appears to be a reasonable assumption for the polar bear data set, as mating can be considered random within the studied population (E. Zeyl, J. Aars, D. Ehrich, L. Bachmann, and Ø. Wiig, unpublished data). The applied likelihood methods further assume that no migrants are entering the population, in other words allele frequencies do not change from one generation to the next. The no-migrant assumption is likely to be violated. However, we consider this only a minor bias because migrants are likely to originate from neighboring populations with similar allele frequencies (Paetkau et al. 1999). Age of males siring litters and time span between litters Age was known with certainty only for bears captured as dependent offsprings with their mother. For bears captured later in life, age was estimated by the count of cementum growth layers of a vestigial premolar tooth (Calvert and Ramsay 1998) or in a few cases based on field observations of body size and tooth wear. In the Barents Sea polar bears, counts of cementum growth layers result in imprecise age estimates; usually the age of younger bears (<7 years) is overestimated, while the age of older bears (‡7 years) is underestimated (Christensen-Dalsgaard 2006). Age estimates based on count of cementum growth layers were available for 544 samples. For 35 samples, age was estimated from field observations (including 22 samples from which only a minimum age estimate could be deduced according to the categories adult, subadult, or cub, and year of capture). Age estimates were lacking for four samples. In the present study, the minimum age difference for parent–offspring pairs was set to 4 years because this age has been reported as the earliest age of female reproduction in the Barents Sea population (Derocher 2005), and because males in the Barents Sea population, according to Lønø (1970), can be sexually mature at 3.5 years. Can. J. Zool. Vol. 87, 2009 Sixty-one fathers were included to determine the age distribution of males siring cubs. The distribution of age at reproduction was compared with the distribution of age at capture of 190 males that could potentially have been mating (‡4 years of age at capture; Fig. 1). When an adult male had been captured several times, it was included several times in the age distribution of captured bears. Similarly, when a male had fathered several litters, it was included several times in the distribution of age at reproduction. The males with several litters were used to estimate the time span between successive litters. Results Multiple paternity and mate fidelity From the total data set of the 583 individuals, parentage analysis revealed 132 mother–offspring relations and 75 father–offspring relations (Zeyl et al. 2009). Twenty-six litters with two siblings and one litter with three siblings from 26 mothers were identified in the field and confirmed genetically (Table 1). For two additional litters observed with their mothers in the field, genetic data were available only for the cubs and not for the mothers. Consequently, only the ML-Relate method could be applied for those two litters. Both parents were assigned for eight litters. The 29 litters were tested for multiple paternity (Table 1). Of those, 27 litters were confirmed to consist of FS. In one litter, the two siblings were confirmed to be HS, showing a case of multiple paternity (M27; Table 1). Neither of the two fathers was identified. Multiple paternity was likely also in one more litter, also with unidentified fathers. However, only Mayor’s method supported the two siblings being HS in this case (M36; Table 1). Twenty females had two to four litters (consisting of one to three offspring) hypothesized to be from different years. Among those 20 females, it was certain that 1 female (M7) reproduced with the same male in two different years (F8; Table 1), as two of the offspring were captured in 2006 as cubs, whereas the third sibling was captured in 2006 at an estimated age of 4 years (cementum growth layers). It is likely that two additional females (M38 and M39; Table 1) had offspring from an identical but unidentified male in different years because two of their respective offspring (O87– O89 and O90–O93), born in different years, turned out to be FS. The age difference between offspring O87–O89 (5 years) and O90–O93 (9 years) makes it unlikely that they were born in a single litter. However, because of the uncertainty of age estimates (Christensen-Dalsgaard 2006), this cannot be firmly ruled out. Among 17 males siring two to four offspring, 8 males had several offspring (FS) born in the same year. In these cases, the mother was identified genetically (M1–M8; Table 1) and had also been observed with the cubs in the field. Twelve males had sired two or three litters in different years. One male certainly had offspring twice with the same female in different years (F8 and M7; Table 2). If the offsprings’ birth years were estimated correctly, another male is likely to have reproduced with the same female in different years (F17, estimated age difference between O117 and O118 was 4 years based on cementum growth layers; Table 2). Published by NRC Research Press Zeyl et al. Comparison between the methods Siblings for which both parents were assigned through parentage analysis allowed us to assess the accuracy of the two statistical methods: ML-Relate and Mayor’s method. In one case, ML-Relate erroneously classified a pair of HS as being FS (O100 and O36, F9; Table 2). Mayor’s method did not reach any incorrect conclusions with the applied settings for acceptance. ML-Relate was inconclusive in three cases where both parents were assigned (M4 and F3, M6 and F8, M8 and F5, F6; Tables 1 and 2) and in one case where only one parent was assigned (F8; Table 2). Mayor’s method was only inconclusive in the M4–F3 case, when using the genotype of the mother (M4; Table 1) but provided a correct result when using the genotype of the father (F3; Table 2). Overall, ML-Relate was inconclusive in 17 of 114 tests (15%) and Mayor’s method was inconclusive in 3 of 126 tests (2%). Thus, we decided to rely on the results provided by Mayor’s method in case of inconsistencies between methods. In total, four inconsistencies between the two methods were observed (Tables 1 and 2). The traditional method did not reveal any contradiction with the results shown by the two other methods. However, very little information was gained using this method, as it was only applicable in 11 siblings groups out of 41 defined through the mother and in 7 siblings groups out of 17 from a common father. Mayor’s method was inconclusive for the siblings O91 and O92 (M39; Table 1); however, the LR was in favour of FS (LR = 1.26). Mayor’s method was also inconclusive for the siblings O52 and O53 (M21; Table 1). The LR was slightly in favour of HS (LR = 0.9). In both cases, ML-Relate concluded FS. For the siblings O7 and O8, the LR test was inconclusive (LR = 0.59) when using the mother’s genotype (M4; Table 1) but was strongly in favour of FS (LR = 956) when using the father’s genotype (F3; Table 2). Thus, we accepted FS. In that case, the relatedness between the identified parents was high (R = 0.19), possibly leading to the inconclusive outcome of one of the LR tests. Both methods identified the case of multiple paternity (M27; Table 1). The relatedness between the siblings was R = 0.2317, which corresponds to what is expected for HS. ML-Relate was not able to distinguish between HS and FS for siblings O82 and O83 (PFS = 0.08; see M36, Table 1). However, Mayor’s method indicated this was another case of multiple paternity (LR = 0.3014). The relatedness between the siblings was high for HS with R = 0.4261. Thus, we considered this case a likely multiple paternity. Relatedness The mean relatedness among the 583 genotyped bears was R = 0.0428 (SD = 0.06, n = 169 653 pairwise comparisons). The mean relatedness between litter mates was close to the mean expected relatedness for FS: R = 0.47 (SD = 0.013, n = 31 pairwise comparisons from 29 litters consisting of 28 duplets and 1 triplet). Offspring sharing the same mother who were hypothesized not to originate from the same litter had a mean relatedness of R = 0.28 (SD = 0.012, n = 56 pairwise comparisons), a value close to the expected relatedness for HS. Confirmed FS had a mean relatedness of R = 0.486 (SD = 0.010, n = 33 pairwise comparisons). Identified reproductive pairs had a mean 1199 relatedness of R = 0.039 (SD = 0.049, n = 21 pairwise comparisons). Incestuous mating We revealed one case of incestuous mating. F18 successfully mated with his daughter O119, resulting in the inbred offspring O121. The relatedness between F18 and O121 was R = 0.7878, and the relatedness between O119 and O121 was R = 0.6251 (Table 2). F18 was heterozygous at 14 of 27 loci; O119 (which is the mother of O121) was heterozygous at 13 of 26 loci (amplification failure of 1 locus); and O121 was heterozygous at 14 of 27 loci. Manual examination of the raw data indicates that individual O121 can have received one allele from F18 and one allele from O119 at each locus. Such high values of relatedness are in line with the assumption of inbreeding. However, when individuals are inbred, a correction for co-ancestry is required to differentiate between HS and FS. This was not done in our analyses. Nevertheless, Mayor’s method appeared more robust than ML-Relate in detecting HS in case of co-ancestry between parents. Age distribution of males siring cubs and mean time span between litters Comparison of the distribution of the males’ age at capture and the age at reproduction revealed that males from 10 to 14 years of age were slightly under-represented among successful fathers, while young males (4–9 years) and bears aged 15–19 years were slightly over-represented (Fig. 1). However, the differences were not significant (ANOVA, F[1,335] = 0.0472, p = 0.8281), indicating that the mean age at capture was not different than the mean age of reproduction. The mean time span between litters sired by the same male was 3.9 years (n = 18, range 1–11 years). Five males sired litters with an interval of 6 years or more (6, 6, 9, 9, and 11 years, respectively). They were between 13 and 23 years old when they sired their last observed litter (13, 17, 15, 23, and 17 years, respectively). Discussion Copulations with multiple males within one breeding period are known to occur in female polar bears (Ramsay and Stirling 1986; Wiig et al. 1992). We document for the first time that this behavior can result in multiple paternities. One multiple paternity was unambiguously identified among 29 litters and in another case multiple paternity was likely. The frequency of multiple paternities in polar bears was expected to be low because of the rather long breeding period in the population, implying asynchronous oestrus among females. Furthermore, the predictability of female locations in the mating season is low because of the large changes in sea-ice distribution. However, a larger data set is needed to statistically compare the frequency of multiple paternity in polar bears with that reported in brown bears (14.5%; Bellemain et al. 2006a). Multiple paternities in bears occur in general at relatively low rates in comparison with other mammals such as rodents (Baker et al. 1999; Burton 2002; Crawford et al. 2008), insectivores (Stockley et al. 1993), or social carnivores (Randall et al. 2007). In the gray redbacked vole (Clethrionomys rufocanus (Sundevall, 1846)), Published by NRC Research Press 1200 Can. J. Zool. Vol. 87, 2009 Table 1. Full-sibling (FS) and half-sibling (HS) assignments (based on traditional, ML-Relate, and Mayor’s methods) of Barents ML-Relate Mother M1a M2a M3a M4a,b M5a M6a M7a,c M8a M9 M10 M11 d M12 M13 M14 M15 M16 M17 M18 M19 M20 e M21 M22 M23 M24 M25 Offspring O1j O2j O3j O4j O5j O6j O7j O8j O9j O10j O11j O12j O13j O14j O15j O16j O17j O18j O19j O20 O21j O22 O23j O24j O25 O26 O27 O28j O29 O30j O31 O32 O33 O34 O35 O36j O37 O38 O39j O40 O41 O42 O43 O44 O45 O46 O47 O48 O49 O50 O51 O52 O53 O54 O55 O56 O57 O56 O57 O58 O59 Birth 2003 2003 2004 2004 2006 2006 2006 2006 2006 2006 2002 2002 2002 2002t 2006 2006 2003 2006 2006 1994 2000t 1995 2000 1998t 2002 1996t 2002t 2003 1995t 2002ft 2003 2003 1993 1993 1997t 2000t 2002 2002 2005 1996 1996 1997 1997 1997 1997 1997 1997 1997 1997 1997 1997 2003 2003 2004 2004 2005 2005 2006 2006 2006 2006 Father F7 F7 F1 F1 F2 F2 F3 F3 F4 F4 F6 F6 F6 F8 F8 F8 F6 F5 F5 Traditional na na na na na Negative Negative Different 1 # # # # # # * * # # # # # # & & na F19 F11 na na Different & & & & * * # # F12 Different & & 3 * # 5 & & & 6 # * & & & & & * & & na na na na na na na na na & & & & & & 12 13 14 15 & & & & * # # & & & & & & na 11 & & & & na 10 & * F21 9 # # & Different 8 # # & F9 7 # # & # # 4 * * F7 F20 2 & & * # # # # # # # # # # * * # # # # * * # # # # Published by NRC Research Press Zeyl et al. 1201 Sea polar bears (Ursus maritimus) as determined through the mother. Mayor’s 16 17 18 19 20 21 1 # # # # # # * * # # # # # # & & 2 & & # # 5 & & & 6 # & & & & & & & 10 11 & & & & & & 12 13 14 15 & & & & & 16 17 18 & & & & 19 20 # # & 21 & & & & & & & & & & & & # # & & & * * 9 # # & # # 8 # # & & & 7 # # & # # 4 # & & & & & & & & & 3 & & & & & & & & & & & & & # # # # # # # # # # # # * * # # # # # # # # Published by NRC Research Press 1202 Can. J. Zool. Vol. 87, 2009 Table 1 (concluded). ML-Relate Mother Offspring Birth M26 O60 O61 O62 O63 O64 O65 O66 O67 O68 O69 O70 O71 O72 O73 O74 O75 O76 O77 O78 O79 O80 O81 O82 O83 O84 O85 O86 O87 O88 O89 O90 O91 O92 O93 O94 O95 O96 O97 2006 2006 2006 2006 1986t 1993t 1987t 1987ft 1987t 1993t 1988t 1991t 1989t 1996 1993t 1996t 1995 1997t 1991t 2004 2004 1995t 2006 2006 1989t 1993t 1996 1992t 1994 1997t 1993t 1994 1994 2002t 2001 2001 1992 1992 M27f M28 M29 M30 M31 M32 M33 M34 M35 M36g M37 M38h M39e (M40)i (M41) Father Traditional na na na na na na na na na Different Different Different Different Different 1 # # & & & & & & & & & & & & & & & & & & & & & & * * & & 2 3 na na 5 # # * 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 & & & & & & # # & # # * * & & & & # & # F22 ?F22 4 * & & # # # # Note: The mothers in parenthesis were determined from field data only. Siblings for which both parents were assigned through parentage analysis when age was determined from tooth cementum growth layers and ‘‘ft’’ indicating when age was determined from field measures of body size denotes no indication that the siblings were sired by different fathers, and ‘‘different’’ denotes that there was indication that the siblings were sired ‘‘&’’s; inconclusive assignments are indicated by ‘‘*’’s. a The ML-Relate test for siblings with both parents assigned by parentage analysis is identical in Tables 1 and 2. Both methods were inconclusive. FS was accepted following Mayor’s method using the father’s genotype. c Female that mated twice with the same male. O15 and O16 were captured as dependent cubs in 2006; O14 was captured as subadult in 2006. d Inconsistency between the two methods. Mayor’s results were accepted (see text). e Mayor’s method was inconclusive. f Multiple paternity accepted. g Likely case of multiple paternity. h Same litter or the female mated twice with the same male. i The probability of being the true father (?F22) was low in this case (p = 0.3), but there were no incompatibilities. See parentage analysis (Zeyl et al. 2009). b Published by NRC Research Press Zeyl et al. 1203 Mayor’s 16 17 18 19 20 21 1 # # & & & & & & & & & & & & & & & & & & & & & & & & & & 2 3 4 5 * * & 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21ghifdeabc & & & & & & # # & # # & & & & & & # & # & & & na na are indicated by ‘‘j’’s. The offsprings’ year of birth appears in boldface type when first captured as juveniles together with their mother, with ‘‘t’’ indicating and tooth-wear examination). The fathers in boldface type also appear in Table 2. For the traditional method, ‘‘na’’ denotes not applicable, ‘‘negative’’ by at least two different fathers. For ML-Relate and Mayor’s methods, FS pairwise relationships are indicated by ‘‘#’’s and HS pairwise relationships by Published by NRC Research Press 1204 Can. J. Zool. Vol. 87, 2009 Table 2. Full-sibling (FS) and half-sibling (HS) assignments (based on traditional, ML-Relate, and Mayor’s methods) of Barents Sea polar bears (Ursus maritimus) as determined through the father. ML-Relate Father F1a a F2 a F3 a F4 a F5 a F6 F7a F8a,b F9c,d F10 F11 F12 F13c F14 F15 c F16 F17e F18f Offspring O3j O4j O5j O6j O7j O8j O9j O10j O18j O19j O17j O11j O12j O13j O21j O1j O2j O98j O14j O99 O15j O16j O100 O36j O101 O102 O103 O24j O104j O105 O106 O28j O107 O108 O109 O110 O111 O112 O113 O114 O115 O116 O117 O118 O119 O120j O121j Birth 2004 2004 2006 2006 2006 2006 2006 2006 2006 2006 2000t 2002 2002 2002 2000t 2003 2003 2005 2002t 2004t 2006 2006 1995 2000t 2002 2003t 1989t 1998t 1999 1992t 2001 2003t 1986t 1997t 1989t 1995t 1990t 1996t 1994t 1995t 1999t 1990t 1991t 1995t 1997t 1998ft 2003t Mother M2 M2 M3 M3 M4 M4 M5 M5 M8 M8 M8 M6 M6 M6 M9 M1 M1 M42 M7 M7 M7 (M43) M14 (M44) Traditional na na na na na Different Different Different 1 # # # # * * # # # # & & 2 3 & & & & & & # na na Different (M46) M12 Different * * & na na na Different Different # # & & & & & & & & * # # & & & & # # * na * * & & # # # # 6 2 3 & & & & & & & & # # # & & & & # & & & & # # & & & & # # & & & & & & & & & & # 6 & & & & & & & & & & # # & # # & & 5 # # # & & & & & & 4 & & & & & & & 1 # # # # # # # # # # & & # # & & * * * * & # # & # # # # * * * * 5 # # & & & 4 & & # M11 M45 M47 O119 Mayor’s na & & # # # # Note: Siblings for which both parents were assigned through parentage analysis are indicated by ‘‘j’’s. The offsprings’ year of birth appears in boldface type when first captured as juveniles together with their mother, with ‘‘t’’ indicating when age was determined from tooth cementum growth layers and ‘‘ft’’ indicating when age was determined from field measures of body size and tooth-wear examination). The mothers in boldface type also appear in Table 1; mothers in parenthesis were determined from field data only. For the traditional method, ‘‘na’’ denotes not applicable, ‘‘negative’’ denotes no indication that the siblings were born by different mothers, and ‘‘different’’ denotes that there was indication that the siblings had at least two different mothers. For ML-Relate and Mayor’s methods, FS pairwise relationships are indicated by ‘‘#’’s and HS pairwise relationships by ‘‘&’’s; inconclusive assignments are indicated by ‘‘*’’s. Data in italic type indicate a father who mated incestuously with his daughter. a The ML-Relate test for siblings with both parents assigned by parentage analysis is identical in Tables 1 and 2. Male mated twice with the same female. O15 and O16 were captured as dependent cubs in 2006. O14 was captured as subadult in 2006. c Inconsistency between the two methods. We accepted Mayor’s results (see text). d Inconsistency with the parentage analysis (with assigned mothers). e Same litter or male mated twice with the same female. f Inbreeding case. The female O119 is believed to be the mother of O121. b Published by NRC Research Press Zeyl et al. 1205 Fig. 1. Histogram representing (a) the relative age distribution densities of adult male polar bears (Ursus maritimus) at capture and (b) the relative age distribution densities of males when they sired cubs. For illustration purpose, we used five age categories (4–9, 10–14, 15–19, 20–24, and 25+ years). The number of observations (n) is shown above each bar. the proportion of litters showing multiple paternities was positively correlated with local density of males around females in oestrus (Ishibashi and Saitoh 2008). Further studies are required to examine whether the frequencies of multiple paternity in polar bears vary among populations with different densities. Uncertainty in age estimation limited our ability to distinguish between litters of siblings identified through a common parent. However, our results indicated that both females and males rarely mated with the same partner in different years. Most consecutive litters were sired by different males. Both female and male polar bears show area fidelity during the breeding season; however, gene flow appears to be slightly male-biased within the Barents Sea population (Zeyl et al. 2009). One could therefore expect that specific females frequently mated with the same neighboring male in different years. However, a relatively high number of available males in most areas may be sufficient to counteract this. Fierce male competition because of a male-biased operational sex ratio should work in the same direction. Accordingly, we detected only one case of incestuous mating. Mating between father and daughter has not been documented previously in polar bears and has been rarely reported in other bear species. A putative case has been mentioned in black bears (Costello et al. 2008). Father– daughter matings were detected in 2 out of 95 litters in Swedish brown bears (Bellemain et al. 2006b). The spatial structure of bears, associated with low recruitment, malebiased dispersal, and male turnover, appears to prevent high rates of incestuous mating. Thus, there is no need for active inbreeding avoidance mechanisms as suggested by Bellemain et al. (2006b) and Costello et al. (2008). The mean relatedness observed between polar bear mating pairs is consistent with the indication that female bears generally do not mate with close relatives, as reported in brown bears (Bellemain et al. 2006b). It has previously been suggested that male polar bears are polygynous (DeMaster and Stirling 1981) and that females are polyandrous (Ramsay and Stirling 1986; Wiig et al. 1992; Molnár et al. 2008). Our results indicate that at least in the Barents Sea, the mating system of polar bears is promiscuous (where males mate with any accessible receptive female and there is no continuing bond between individual males and females after mating has occurred. Females usually mate with different males in successive breeding attempts. In some species, females mate with several different males during each period of receptivity, whereas in others, they typically mate with a single male; Clutton-Brock 1989). Since this conclusion is only based on a limited number of litters, it should be taken with caution. Nevertheless, the results are in accordance with Clutton-Brock (1989), who predicted a promiscuous mating system when females are widely and unpredictably distributed. The mating system of a species is plastic: there is a correlation between the mating system and population densities (Kokko and Rankin 2006). In swift foxes (Vulpes velox (Say, 1823)), the mating system is polygynous in high-density areas, whereas it is monogamous in low-densities areas (Kamler et al. 2004). In European water voles (Arvicola terrestris (L., 1758)), consecutive litters were found fathered by a single male in lowdensity populations and usually by different males in a highdensity population (Aars et al. 2006). The Barents Sea has a moderate to high polar bear density compared with several other areas, but local densities are variable (Aars et al. 2009). A lower density of available breeders within a population that can, e.g., be caused by excessive hunting may induce a change in the mating system of the animals within the area. If human hunting of polar bears is not male-biased, or if no hunting occurs such as in the Barents Sea population, the adult sex ratio become close to 1:1. As many females in the mating season are with cubs and unavailable for mating, more males than females will be available for Published by NRC Research Press 1206 Can. J. Zool. Vol. 87, 2009 mating (Bunnell and Tait 1981; Ramsay and Stirling 1986). Male-biased OSR is expected to favor numerous mating encounters for females (DeYoung et al. 2002). Indeed, field observations indicate that female polar bears in oestrus may copulate with several males (Ramsay and Stirling 1986; Wiig et al. 1992). In contrast, very low densities and a closer to even OSR, e.g., in areas with male-biased hunting could lead to a more monogamous mating system. In black bears, paternity analyses revealed that male reproductive success was dominated by intermediate-aged bears (Costello et al. 2008), which indicates that most males would have a relatively short reproductive tenure. This is congruent with the observation of Ramsay and Stirling (1986) who reported that male polar bears associated with adult females were, on average, older (median = 10.5 years of age) than solitary males (median = 8 years of age). Taking into account the growth pattern in male polar bears, we expected that males belonging to the age class 15–19 would sire most litters. It also corresponds to the period when the foreleg guard hairs, which are hypothetized to be a sexual ornament, reach their maximum length (Derocher et al. 2005) and when most wounds and scars are observed on males (A.E. Derocher et al., submitted).2 Sexual dimorphism can be maintained through sexual selection, with larger body size in males being correlated to higher reproductive success through a better access to females (Andersson 1994). In general, the size difference in polar bears is large (Derocher et al. 2005), indicating that male competition for females is fierce. Our data set was not large enough to test with high statistical power for smaller differences in age for male reproductive success, but showed that such differences seemed small, contrary to our expectation. Some care should be taken in any conclusion based on a comparison between the age distribution of males at capture and the age distribution of males when siring cubs. The youngest males are underrepresented in the capture data owing to lower trapability (Derocher 2005). Older males that sired cubs may have lower survival rates and less chance of being captured. The main conclusion that reproductive success of adult males of different ages were unlikely do differ profoundly still seems to hold. Our results suggest that the male’s size and age might be less indicative of the reproductive success than previously thought. The distribution of female polar bears during the mating season is influenced by the distribution and accessibility of their main prey (Stirling et al. 1993), which in the spring is ringed seal (Pusa hispida (Schreber, 1775); Derocher et al. 2002). The prime habitat of ringed seals in Svalbard is near glacier fronts in sheltered fjords and bays (Smith and Lydersen 1991). The distribution of males in spring appears to be correlated with the distribution of females available for reproduction (Ramsay and Stirling 1986; Stirling et al. 1993). Consequently, some areas have higher local bear densities than others (Wiig et al. 1992). This might influence the pattern of age-related reproduction in males because the level of competition between males may vary with density. Indeed, in some species, fluctuations in population densities might alter the outcome in the breeding success of males of 2 A.E. different age classes. In the Saint Kilda population of promiscuous Soay sheep (Ovis aries L., 1758), the level of male–male competition for mates varies with population size and sex ratio. Old males sire larger sibships (i.e., a group of offsprings produced by a male) than young males at low population size when polygyny of old males is also maximal. However, the size of sibships sired by young males is small at any population size (Pemberton et al. 1999). In polar bears, both scramble competition (males disperse to find receptive females) and contest competition (males fight to establish dominance over other males to get access to females) are believed to occur (A.E. Derocher et al., submitted).2 Sequestration and herding of females toward low-density areas could be advantageous for younger males because it reduces the probability of encountering older males with superior fighting abilities. Some field observations indicate that males might herd females in the Barents Sea population (Wiig et al. 1992), and this behavior has also been reported in Canadian polar bears (Ramsay and Stirling 1986). The mountains and glaciers from the Svalbard archipelago might offer multiple herding opportunities for young males. Thus, the observed absence of age-related breeding success in male polar bears could be related to the mechanism of intermale competition to gain breeding opportunities. The landscape in the Barents Sea might favor a high proportion of young males being able to gain breeding opportunities. The relation between age and breeding success of males may vary between populations according to landscape characteristics, to the distribution of seals, and local bear densities. Limitation of the statistical analysis Costello et al. (2008) found that ML-Relate was likely to infer genetic relationships between individuals to be closer than they were. This seemed indeed to explain some inconsistencies between ML-Relate and Mayor’s method in this study. However, ML-Relate also failed to distinguish between alternative relationships (FS and HS) in cases where siblings were FS. This might be due to a violation of the assumption of co-ancestry between parents, to the presence of groups of relatives in the data set, or this could also arise because some parents might present genotypes with rare alleles. Indeed, this would influence the discriminating power of the methods. Further studies evaluating the robustness of those methods to hypothesis violation would be welcome. The analysis performed with Mayor’s method appeared to be more reliable than the results based on ML-Relate. This is not surprising, as Mayor’s method uses the additional information provided by the genotype of one of the parents. Moreover, both ML-Relate and Mayor’s method are able to provide more information than the traditional method of parental allele counts, which is applicable only within groups of n ‡ 3 siblings when searching for multiple paternities and studying the mating system of a species. These statistical methods allow the detection of HS within litters with only two siblings, and thus are likely to provide a better estimate of the minimal rate of multiple paternities than the traditional method. Derocher, J. Aars, M. Andersen, and Ø. Wiig. Mating ecology of polar bears at Svalbard. Submitted for publication. Published by NRC Research Press Zeyl et al. Acknowledgements We are grateful to Lianne Dance (previously Mayor) for kindly providing the scripts necessary to perform the analysis. We thank the anonymous reviewers for their constructive comments. This work was supported by the Natural History Museum of the University of Oslo, Norway, and the Norwegian Research Council through the National Centre for Biosystematics (project no. 146515/420). Samples were provided by the Norwegian Polar Institute (Tromsø, Norway). References Aars, J., Dallas, J.F., Piertney, S.B., Marshall, F., Gow, J.L., Telfer, S., and Lambin, X. 2006. Widespread gene flow and high genetic variability in populations of water voles Arvicola terrestris in patchy habitats. Mol. Ecol. 15(6): 1455–1466. doi:10.1111/j. 1365-294X.2006.02889.x. PMID:16629803. Aars, J., Marques, T.A., Buckland, S.T., Andersen, M., Belikov, S., Boltunov, A.N., and Wiig, Ø. 2009. Estimating the Barents Sea polar bear subpopulation size. Mar. Mamm. Sci. 25(1): 35–52. doi:10.1111/j.1748-7692.2008.00228.x. Andersson, M. 1994. Sexual selection. Princeton University Press, Princeton, N.J. Baker, R.J., Makova, K.D., and Chesser, R.K. 1999. Microsatellites indicate a high frequency of multiple paternity in Apodemus (Rodentia). Mol. Ecol. 8(1): 107–111. doi:10.1046/j.1365-294X. 1999.00541.x. PMID:12187947. Bellemain, E., Swenson, J.E., and Taberlet, P. 2006a. Mating strategies in relation to sexually selected infanticide in a non-social carnivore: the brown bear. Ethology, 112(3): 238–246. doi:10. 1111/j.1439-0310.2006.01152.x. Bellemain, E., Zedrosser, A., Manel, S., Waits, L., Taberlet, P., and Swenson, J.E. 2006b. The dilemma of female mate selection in the brown bear, a species with sexually selected infanticide. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 273(1584): 283–291. doi:10. 1098/rspb.2005.3331. Boness, D.J. 1991. Chap. 1. Determinants of mating systems in the Otariidae (Pinnipedia). In Behaviour of pinnipeds. Edited by Deane Renouf. Chapman and Hall, Bristol, UK. pp. 1–44. Boness, D.J., Bowen, W.D., and Oftedal, O.T. 1988. Evidence of polygyny from spatial patterns of hooded seals (Cystophora cristata). Can. J. Zool. 66(3): 703–706. doi:10.1139/z88-104. Bonin, A., Bellemain, E., Bronken Eidesen, P., Pompanon, F., Brochmann, C., and Taberlet, P. 2004. How to track and assess genotyping errors in population genetics studies. Mol. Ecol. 13(11): 3261– 3273. doi:10.1111/j.1365-294X.2004.02346.x. PMID:15487987. Bunnell, F.L., and Tait, D.E.N. 1981. Population dynamics of bears — implications. In Dynamics of large mammal populations. Edited by C.W. Fowler and B.R. Smith. John Wiley and Sons, New York. pp. 75–98. Burton, C. 2002. Microsatellite analysis of multiple paternity and male reproductive success in the promiscuous snowshoe hare. Can. J. Zool. 80(11): 1948–1956. doi:10.1139/z02-187. Calvert, W., and Ramsay, M. 1998. Evaluation of age determination of polar bears by counts of cementum growth layer groups. Ursus, 10: 449–453. Cassini, M.H. 1999. The evolution of reproductive systems in pinnipeds. Behav. Ecol. 10(5): 612–616. doi:10.1093/beheco/10.5. 612. Cercueil, A., Bellemain, E., and Manel, S. 2002. PARENTE: computer program for parentage analysis. J. Hered. 93(6): 458–459. doi:10.1093/jhered/93.6.458. PMID:12642650. 1207 Christensen-Dalsgaard, S.N. 2006. Temporal patterns in age structure of polar bears (Ursus maritimus) in Svalbard, with special emphasis on validation of age determination. M.Sc. thesis, Faculty of Science, University of Tromsø and Norwegian Polar Institute, Tromsø, Norway. Clutton-Brock, T.H. 1989. Review lecture: Mammalian mating systems. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 236(1285): 339–372. doi:10.1098/rspb.1989.0027. PMID:2567517. Costello, C.M., Creel, S.R., Kalinowski, S.T., Vu, N.V., and Quigley, H.B. 2008. Sex-biased natal dispersal and inbreeding avoidance in American black bears as revealed by spatial genetic analyses. Mol. Ecol. 17(21): 4713–4723. doi:10.1111/j.1365294X.2008.03930.x. PMID:18828781. Crawford, J.C., Liu, Z., Nelson, T.A., Nielsen, C.K., and Bloomquist, C.K. 2008. Microsatellite analysis of mating and kinship in beavers (Castor canadensis). J. Mammal. 89(3): 575–581. doi:10.1644/07-MAMM-A-251R1.1. Crompton, A.E., Obbard, M.E., Petersen, S.D., and Wilson, P.J. 2008. Population genetic structure in polar bears (Ursus maritimus) from Hudson Bay, Canada: implications of future climate change. Biol. Conserv. 141(10): 2528–2539. doi:10.1016/j. biocon.2008.07.018. Davies, N.B., and Lundberg, A. 1984. Food distribution and a variable mating system in the dunnock, Prunella modularis. J. Anim. Ecol. 53(3): 895–912. doi:10.2307/4666. DeMaster, D.P., and Stirling, I. 1981. Ursus maritimus. Mamm. Species, 145(145): 1–7. doi:10.2307/3503828. Derocher, A.E. 2005. Population ecology of polar bears at Svalbard, Norway. Popul. Ecol. 47(3): 267–275. doi:10.1007/ s10144-005-0231-2. Derocher, A.E., and Stirling, I. 1998. Geographic variation in growth of polar bears (Ursus maritimus). J. Zool. (Lond.), 245(1): 65–72. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7998.1998.tb00072.x. Derocher, A.E., Stirling, I., and Calvert, W. 1997. Male-biased harvesting of polar bears in western Hudson Bay. J. Wildl. Manage. 61(4): 1075–1082. doi:10.2307/3802104. Derocher, A.E., Wiig, Ø., and Andersen, M. 2002. Diet composition of polar bears in Svalbard and the western Barents Sea. Polar Biol. 25: 448–452. doi:10.1007/s00300-002-0364-0. Derocher, A.E., Andersen, M., and Wiig, Ø. 2005. Sexual dimorphism of polar bears. J. Mammal. 86(5): 895–901. doi:10.1644/ 1545-1542(2005)86[895:SDOPB]2.0.CO;2. DeYoung, R.W., Demarais, S., Gonzales, R.A., Honeycutt, R.L., and Gee, K.L. 2002. Multiple paternity in white-tailed deer (Odocoileus virginianus) revealed by DNA microsatellites. J. Mammal. 83(3): 884–892. doi:10.1644/1545-1542(2002)083<0884:MPIWTD>2.0. CO;2. Dyck, M.G. 2006. Characteristics of polar bears killed in defense of life and property in Nunavut, Canada, 1970–2000. Ursus, 17(1): 52–62. doi:10.2192/1537-6176(2006)17[52:COPBKI]2.0. CO;2. Ferguson, S.H., Taylor, M.K., Born, E.W., and Messier, F. 1998. Fractals, sea-ice landscape and spatial patterns of polar bears. J. Biogeogr. 25: 1081–1092. Gehrt, S.D., and Fritzell, E.K. 1998. Resource distribution, female home range dispersion and male spatial interactions: group structure in a solitary carnivore. Anim. Behav. 55(5): 1211– 1227. doi:10.1006/anbe.1997.0657. PMID:9632506. Hosken, D.J., and Stockley, P. 2003. Benefits of polyandry: a life history perspective. Evol. Biol. 33: 173–194. Ims, R.A. 1988. The potential for sexual selection in males: effect of sex ratio and spatiotemporal distribution of receptive females. Evol. Ecol. 2(4): 338–352. doi:10.1007/BF02207565. Ishibashi, Y., and Saitoh, T. 2008. Effect of local density of males Published by NRC Research Press 1208 on the occurrence of multimale mating in gray-sided voles (Myodes rufocanus). J. Mammal. 89(2): 388–397. doi:10.1644/ 07-MAMM-A-036.1. Isvaran, K., and Clutton-Brock, T. 2007. Ecological correlates of extra-group paternity in mammals. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 274(1607): 219–224. doi:10.1098/rspb.2006.3723. Jones, A.G., and Ardren, W.R. 2003. Methods of parentage analysis in natural populations. Mol. Ecol. 12(10): 2511–2523. doi:10. 1046/j.1365-294X.2003.01928.x. PMID:12969458. Kalinowski, S.T., Wagner, A.P., and Taper, M.L. 2006. ML-Relate: a computer program for maximum likelihood estimation of relatedness and relationship. Mol. Ecol. Notes, 6(2): 576–579. doi:10.1111/j.1471-8286.2006.01256.x. Kamler, J.F., Ballard, W.B., Lemons, P.R., and Mote, K. 2004. Variation in mating system and group structure in two populations of swift foxes, Vulpes velox. Anim. Behav. 68(1): 83–88. doi:10.1016/j.anbehav.2003.07.017. Kokko, H., and Rankin, D.J. 2006. Lonely hearts or sex in the city? Density-dependent effects in mating systems. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 361(1466): 319–334. doi:10.1098/rstb. 2005.1784. PMID:16612890. Kovacs, K.M. 1995. Harp and hooded seal reproductive behavior and energetics — A case study in the determinants of mating systems in pinnipeds. In Whales, seals, fish and man. Edited by A. Schytte-Blix, L. Walloe, and O. Ulltang. Elsevier Science B, Amsterdam, the Netherlands. pp. 329–335. Kovacs, K.M., Lydersen, C., Hammill, M.O., White, B.N., Wilson, P.J., and Malik, S. 1997. A harp seal hooded seal hybrid. Mar. Mamm. Sci. 13(3): 460–468. doi:10.1111/j.1748-7692. 1997.tb00652.x. Le Boeuf, B.J. 1991. Pinniped mating systems on land, ice and in the water: emphasis on the Phocidae. In Behaviour of pinnipeds. Edited by Deane Renouf. Chapman and Hall, Bristol, UK. pp. 45–65. Le Boeuf, B.J., and Reiter, J. 1988. Lifetime reproductive success in northern elephant seals. In Reproductive success. Edited by T.H. Clutton-Brock. University of Chicago Press, Chicago. pp. 344–362. Lønø, O. 1970. The polar bear (Ursus maritimus Phipps) in the Svalbard area. Norsk Polarinstitutt Skrifter. No. 149. Mayor, L.R., and Balding, D.J. 2006. Discrimination of half-siblings when maternal genotypes are known. Forensic Sci. Int. 159(2-3): 141–147. doi:10.1016/j.forsciint.2005.07.007. PMID:16153794. McLoughlin, P.D., Taylor, M.K., and Messier, F. 2005. Conservation risks of male-selective harvest for mammals with low reproductive potential. J. Wildl. Manag. 69: 1592–1600. doi:(2005)69[1592:CROMHF]2.0.CO;2. doi:10.1016/j.forsciint. 2005.07.007. PMID:16153794. McRae, S.B., and Kovacs, K.M. 1994. Paternity exclusion by DNA fingerprinting, and mate guarding in the hooded seal Cystophora cristata. Mol. Ecol. 3(2): 101–107. doi:10.1111/j.1365-294X. 1994.tb00110.x. PMID:8019687. Molnár, P.K., Derocher, A.E., Lewis, M.A., and Taylor, M.K. 2008. Modelling the mating system of polar bears: a mechanistic approach to the Allee effect. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 275(1631): 217–226. doi:10.1098/rspb.2007.1307. Morrissey, M.B., and Wilson, A.J. 2005. The potential costs of accounting for genotypic errors in molecular parentage analyses. Mol. Ecol. 14(13): 4111–4121. doi:10.1111/j.1365-294X.2005. 02708.x. PMID:16262862. Paetkau, D., and Strobeck, C. 1994. Microsatellite analysis of genetic variation in black bear populations. Mol. Ecol. 3(5): 489– 495. doi:10.1111/j.1365-294X.1994.tb00127.x. PMID:7952329. Paetkau, D., Amstrup, S.C., Born, E.W., Calvert, W., Derocher, Can. J. Zool. Vol. 87, 2009 A.E., Garner, G.W., Messier, F., Stirling, I., Taylor, M.K., Wiig, Ø., and Strobeck, C. 1999. Genetic structure of the world’s polar bear populations. Mol. Ecol. 8(10): 1571–1584. doi:10.1046/j.1365-294x.1999.00733.x. PMID:10583821. Peakall, R., and Smouse, P. 2006. GENALEX 6: genetic analysis in Excel. Population genetic software for teaching and research. Mol. Ecol. Notes, 6(1): 288–295. doi:10.1111/j.1471-8286.2005. 01155.x. Pemberton, J.M., Coltman, D.W., Smith, J.A., and Pilkington, J.G. 1999. Molecular analysis of a promiscuous, fluctuating mating system. Biol. J. Linn. Soc. 68(1-2): 289–301. doi:10.1111/j. 1095-8312.1999.tb01170.x. Prestrud, P., and Strirling, I. 1994. The international polar bear agreement and the current status of polar bear conservation. Aquat. Mamm. 20: 113–124. Ramsay, M.A., and Stirling, I. 1986. On the mating system of polar bears. Can. J. Zool. 64: 2142–2151. doi:10.1139/z86-329. Randall, D.A., Pollinger, J.P., Wayne, R.K., Tallents, L.A., Johnson, P.J., and Macdonald, D.W. 2007. Inbreeding is reduced by female-biased dispersal and mating behavior in Ethiopian wolves. Behav. Ecol. 18(3): 579–589. doi:10.1093/beheco/ arm010. Raymond, M., and Rousset, F. 1995. GENEPOP (version 1.2): population genetics software for exact tests and ecumenicism. J. Hered. 86: 248–249. R Development Core Team. 2008. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria. Available from http://www.r-project.org/ [accessed 30 October 2008]. Rosing-Asvid, A., Born, E.W., and Kingsley, M.C.S. 2002. Age at sexual maturity of males and timing of the mating season of polar bears (Ursus maritimus) in Greenland. Polar Biol. 25: 878– 883. doi:10.1007/s00300-002-0430-7. Sambrook, J., and Russell, D.W. 2001. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, New York. Say, L., Pontier, D., and Natoli, E. 1999. High variation in multiple paternity of domestic cats (Felis catus L.) in relation to environmental conditions. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 266: 2071– 2074. doi:10.1098/rspb.1999.0889. Schenk, A., and Kovacs, K.M. 1995. Multiple mating between black bears revealed by DNA fingerprinting. Anim. Behav. 50(6): 1483–1490. doi:10.1016/0003-3472(95)80005-0. Sinclair, E.A., Black, H.L., and Crandall, K.A. 2003. Population structure and paternity in an american black bear (Ursus americanus) population using microsatellite DNA. West. N. Am. Nat. 63: 489–497. Smith, T.G., and Lydersen, C. 1991. Availability of suitable landfast ice and predation as factors limiting ringed seal populations, Phoca hispida, in Svalbard. Polar Res. 10(2): 585–594. doi:10. 1111/j.1751-8369.1991.tb00676.x. Stirling, I., Andriashek, D., and Calvert, W. 1993. Habitat preference of polar bears in the western Canadian Arctic in late winter and spring. Polar Rec. (Gr. Brit.), 29(168): 13–24. doi:10.1017/ S0032247400023172. Stockley, P., Searle, J.B., Macdonald, D.W., and Jones, C.S. 1993. Female multiple mating behaviour in the common shrew as a strategy to reduce inbreeding. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 254(1341): 173–179. doi:10.1098/rspb.1993.0143. Taylor, M., McLoughlin, P.D., and Messier, F. 2008. Sex-selective harvesting of polar bears Ursus maritumus. Wildl. Biol. 14: 52– 60. doi:0.2981/0909–6396(2008)14[52:SHOPBU]2.0.CO;2. Tumanov, I.L. 2001. Reproductive biology of captive polar bears. Ursus, 12: 107–108. Published by NRC Research Press Zeyl et al. Waits, L.P., Luikart, G., and Taberlet, P. 2001. Estimating the probability of identity among genotypes in natural populations: cautions and guidelines. Mol. Ecol. 10(1): 249–256. doi:10. 1046/j.1365-294X.2001.01185.x. PMID:11251803. Wiig, Ø. 1995. Distribution of polar bears (Ursus maritimus) in the Svalbard area. J. Zool. (Lond.), 237(4): 515–529. doi:10.1111/j. 1469-7998.1995.tb05012.x. Wiig, Ø., and Derocher, A.E. 1999. Application of aerial survey methods to polar bears in the Barents Sea. In Marine mammal survey and assessment methods. Edited by G.W. Garner, S.C. 1209 Amstrup, J.L. Laake, B.F.J. Manly, L.L. McDonald, and D.G. Robertson. A.A. Bolkema Publishers, Rotterdam, Holland. pp. 27–36. Wiig, Ø., Gjertz, I., Hansson, R., and Thomassen, J. 1992. Breeding behaviour of polar bears in Hornsund, Svalbard. Polar Rec. (Gr. Brit.), 28(165): 157–159. doi:10.1017/S0032247400013474. Zeyl, E., Aars, J., Ehrich, D., and Wiig, Ø. 2009. Families in space: relatedness in the Barents Sea population of polar bears (Ursus maritimus). Mol. Ecol. 18(4): 735–749. doi:10.1111/j.1365294X.2008.04049.x. PMID:19175504. Published by NRC Research Press