MELLON-MIT FOUNDATION ON NGOs AND FORCED MIGRATION ILLEGAL IMMIGRATION FROM

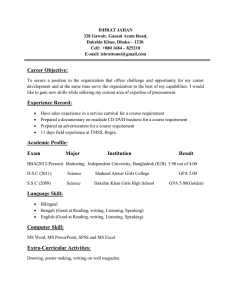

advertisement