Working Paper #30 Life in Khartoum: Probing Forced Migration

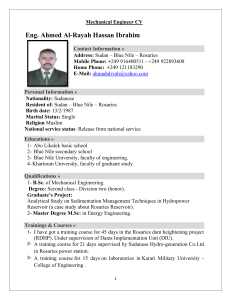

advertisement