SUSTAINABILITY AND HISTORIC FEDERAL BUILDINGS

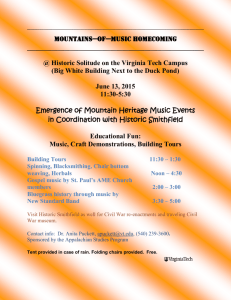

advertisement