A PARADIGM FOR KEMETIC ARCHITECTURAL DESIGN: KEMETIC ARCHITECTURAL

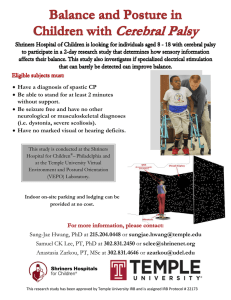

advertisement