Fatty acid-activated nuclear transcription factors and their roles in human placenta

advertisement

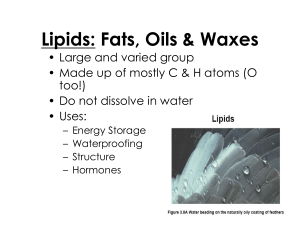

70 DOI 10.1002/ejlt.200500272 Asim K. Duttaroy Fatty acid-activated nuclear transcription factors and their roles in human placenta Department of Nutrition, Institute of Basic Medical Sciences, Faculty of Medicine, University of Oslo, Norway Eur. J. Lipid Sci. Technol. 108 (2006) 70–83 Emerging evidence indicates that fatty acid-activated nuclear transcription factors play very important and complex roles in placental biology. These fatty acid-activated receptors are involved at a number of different levels such as differentiation, proliferation, and hormone synthesis in the feto-placental unit. Since these receptors are also fatty acid sensors, they may be involved in placental fatty acid transport and metabolism. The present article is a review of the complex roles of peroxisome proliferatoractivated receptors, sterol regulatory element-binding proteins and liver X receptors in placental biology. Keywords: PPAR, fatty acid uptake, SREBP, LXR, Placenta. Review Paper 1 Introduction Human placental transport of long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acids (LC-PUFA) from the maternal circulation into the fetal circulation is essential for proper fetal growth and development [12–14]. During this period, recruitment of maternal LC-PUFA, mainly docosahexaenoic acid (DHA, 22:6n-3) and arachidonic acid (ARA, 20:4n-6), is critical for rapid brain and other tissue growth [2, 13, 15, 16]. Several fatty acid-binding and transport proteins are thought to be responsible for effective uptake of maternal plasma fatty acids by the placental trophoblast [17]. Recent studies indicate that PPAR may be responsible for regulating the expression of fatty acid transport or binding proteins in tissues such as adipose, liver and skeletal muscle [18–22]. On the other hand, fatty acids and their oxygenated derivatives directly or indirectly regulate several cellular processes such as differentiation, development and gene expression in tissues through PPAR [23, 24]. Therefore, it is very likely that these nuclear receptors may also be involved in placental fatty acid uptake by modulating expression of fatty acid transport proteins [25–27]. The main aim of this review is to discuss the complex and diverse roles of these fatty acid-activated transcription receptors [i.e. PPAR, sterol regulatory element-binding proteins (SREBP) and liver X receptors (LXR)] in feto-placental growth, development and fatty acid transport function. The human placenta performs several important functions essential for the maintenance of pregnancy and development of the fetus [1]. The human placenta is a hemochorial placenta and therefore provides direct access to the maternal blood for nutrients like glucose, fatty acids, and amino acids [1, 2]. Placental trophoblast cell invasion of uterine tissues and remodeling of uterine spiral arterial walls ensure that the developing feto-placental unit receives the necessary supply of blood and that efficient transfer of nutrients and gases and the removal of wastes can take place. Implantation and the formation of the placenta therefore is a highly coordinated process involving interaction between maternal and embryonic cells. Changes in placental development and function have dramatic effects on the fetus and its ability to cope with the intra-uterine environment. Insufficient growth in utero is associated with diseases of adulthood, such as diabetes, hypertension, and cardiovascular disease [3]. Emerging evidence suggests that peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors (PPAR) are critical players in growth, development and physiological functions of the feto-placental axis [4–7]. These fatty acid-activated nuclear transcription factors also regulate expression of genes responsible for several placental functions including trophoblast invasion, nutrient transport, and hormone synthesis. All PPAR subtypes are present in human placenta and their diverse biological roles have been increasingly realized in placental biology [8–11]. 2 Nuclear transcription factors in human placenta Correspondence: Asim K. Duttaroy, Department of Nutrition, Institute of Basic Medical Sciences, Faculty of Medicine, University of Oslo, P.O. Box 1046 Blindern, N-0316 Oslo, Norway. Phone: 147 22851547, Fax: 147 22851341, e-mail: a.k.dutta roy@medisin.uio.no Nuclear receptors comprise a large family of ligand-regulated transcription factors [28]. They have been divided into two groups: class I nuclear receptors comprising steroid hormone receptors, and class II nuclear receptors which are still named “orphans” because their ligands © 2006 WILEY-VCH Verlag GmbH & Co. KGaA, Weinheim www.ejlst.com Eur. J. Lipid Sci. Technol. 108 (2006) 70–83 have not yet been identified. The modular structure of nuclear receptors is generally conserved in almost all the members of this superfamily (Fig. 1). The structure includes the A/B domain, containing a ligand-independent transcription activation function (AF-1) at the N terminus; the C domain containing a DNA-binding domain (DBD), characterized by two typical zinc-fingers that are involved in the recognition of specific DNA consensus sequences; and the D domain which confers flexibility on the receptor for proper dimerization and for interaction with the DNA consensus sequences located on target genes [29, 30]. The E domain consists of the ligand-binding domain (LBD), a hydrophobic pocket that can accommodate the selective ligand for the receptor, and the ligand-dependent transcription activation function (AF-2). The F domain is present in some nuclear receptors and seems to negatively modulate the transcription activity of the receptor [31, 32]. Upon binding of the ligand, the receptor undergoes a conformational change that exposes a-helix 12, the surface for interaction with transcription co-activators, which has been identified as the AF-2 of the receptor [33]. At the same time, the structural modifications elicited by the ligand decrease the affinity to co-repressors, which are released from the receptors [29–32, 34]. However, nuclear receptors can also be regulated in a ligand-independent fashion through the AF-1. Post-translational modifications such as phosphorylation [35, 36] have been reported to modulate receptor activity. Co-activators and corepressors interacting with nuclear receptors regulate the rate of transcription initiation not only by interacting with proteins of the pre-initiation complex and engaging RNA polymerase II [37], but also by recruiting histone acetyl Fig. 1. Schematic representation of a nuclear receptor. A typical nuclear receptor is composed of several functional domains. The variable N-terminal region (A/B) contains the ligand-independent AF-1 transactivation domain. The conserved DBD is responsible for the recognition of specific DNA sequences. A variable linker region D connects the DBD to the conserved E/F region that contains the LBD as well as the dimerization surface. The ligand-independent transcriptional activation domain is contained within the A/B region, and the ligand-dependent AF-2 core transactivation domain within the C-terminal portion of the LBD. © 2006 WILEY-VCH Verlag GmbH & Co. KGaA, Weinheim PPARs and their roles in human placenta 71 transferases (HAT) or histone deacetylases (HDAC). Some of these co-regulators are also part of the HAT or HDAC complex. HAT and HDAC have opposite effects on the nucleosomal structure and local chromatin assembly and, consequently, they also play a key role in the activation and repression of gene transcription, respectively, by affecting the accessibility of transcription factors to the DNA and the epigenetic marking system constituting the so-called “histone code” [38]. 3 PPAR in human placental trophoblasts PPAR are members of the nuclear receptor superfamily of transcription factors that includes steroid receptors [28]. They bind fatty acids and their oxygenated metabolites and so were identified as regulators of lipid homeostasis. These receptors are involved in a wide variety of physiological processes ranging from cell differentiation, inflammatory response and regulation of vascular biology to reproductive biology, as well as in pathological conditions such as type II diabetes, atherosclerosis and cancers [8– 11, 39]. There are three PPAR subtypes, termed PPARa, PPARd (also referred to as PPARb, NUC1, or FAAR) and PPARg. Analysis of their gene sequences shows that the three PPAR genes are probably derived from a common ancestral gene. PPAR have a similar structural and functional organization to other nuclear receptors [40]. The PPAR are expressed in a broad range of tissues in both rodents and humans [41–44]. PPARa is expressed in liver, kidney, heart, gut, brain, adipose tissue, retina and skeletal muscle in rodents, while in humans it has been shown to be expressed in heart, placenta, lung, liver, muscle, kidney, pancreas and adipose tissue [42–45]. PPARd appears to be expressed ubiquitously, with expression being similar for both rodents and humans [41, 46, 47]. PPARg shows much more restricted expression than PPARa or d. PPARg is expressed in adipose tissue, intestine and immune cells, and at much lower levels in muscle, liver, heart, kidney, pancreas and retina [45, 47–50]. Three forms of PPARg are known and are termed PPARg1, g2 and g3 [51]. PPARg1 has higher levels of expression than PPARg2, which is expressed only in adipose tissue, colon and liver [52]. Expression of PPARg3 mRNA is restricted to adipose tissue and colon, similar to that of PPARg2 [53]. Binding of a ligand to the LBD leads to heterodimerization of the PPAR to the retinoid X receptor (RXR) and, subsequently, binding of the complex to a peroxisome proliferator response element (PPRE) on the target gene, which leads to gene transcription [54]. By analysis of the promoters of several other peroxisome proliferatorresponsive genes, a PPRE sequence motif was defined as two direct TG(A/T)CCT repeats, known as half-sites, www.ejlst.com 72 A. K. Duttaroy separated by a single nucleotide and thus called a direct repeat one (DR1). PPRE located at variable distances upstream of the transcription initiation site have been identified in other genes known to be activated by peroxisome proliferators, including genes encoding peroxisomal, microsomal, mitochondrial, nuclear, and cytosolic or extracellular proteins [55–57]. Comparison of PPRE sequences with the DNA-binding motifs of other nuclear receptors, including the thyroid hormone receptor (TR), the retinoic acid receptor (RAR), RXR, and the vitamin D3 receptor (VDR), revealed that these receptors all recognize the same half-site sequence motifs (TGACCT). Like PPAR, these receptors bind to direct repeats as heterodimers with a common partner, RXR. The relative spacing and orientation of the half-site motifs determine which nuclear receptor-RXR heterodimer binds to the response element. The RXR heterodimers with RAR, TR, VDR, RAR, and PPAR recognize direct repeats separated by five, four, three, two, or one nucleotide, respectively. A number of studies point to the importance of the sequences flanking the PPRE for maintaining the optimal conformation of the PPAR-RXR heterodimer on the PPRE [58]. Not all of the PPRE in responsive genes act to mediate increases in transcription. A growing number of genes, including transthyretin, some apolipoprotein genes, transferrin, and hepatocyte nuclear factor-4, possess DR1-like motifs but are negatively regulated by peroxisome proliferators through PPAR. PPAR may negatively regulate some genes through DR1-like elements by competing for binding to the DR1 with other nuclear receptors that constitutively activate expression [58]. In addition to PPAR, gene targeting studies in mice have demonstrated a critical role for RXRa also in feto-placental development [59]; however, this review will concentrate only on the roles of the PPAR, LXR, and SREBP. 3.1 PPARÆ The importance of PPARa in placental biology is relatively small compared with that of the other two PPAR [5]. PPARa mRNA has been detected in amnion, choriodecidua, placental syncytial and cytotrophoblast cells at term, as well as in placental choriocarcinoma (BeWo) cell lines [5, 60, 61]. PPARa, however, may not be essential for feto-placental biology [62]. Unlike the situation in PPARg and PPARd knockout mice, normal fertility was observed in PPARa knockout mice. The few available data suggest the existence of metabolic roles of PPARa in placenta. A PPARa agonist, clofibric acid, was reported to suppress proliferation of the trophoblast cell line JEG-3 by stimulating p53 expression [63]. Hashimoto et al. studied the effect of PPARa agonists on cell growth and © 2006 WILEY-VCH Verlag GmbH & Co. KGaA, Weinheim Eur. J. Lipid Sci. Technol. 108 (2006) 70–83 function of the immortalized human extravillous trophoblast cell line TCL.1 [64]. Both gemfibrozil and clofibrate inhibited proliferation of these cells and secretion of human chorionic gonadotrophin (hCG). Moreover, PPARa was suggested to be involved in the development of the fetal epidermal barrier [65, 66]. PPARa agonists accelerated epidermal barrier development in skin explants from fetal rats in vitro [65]. However, further studies are warranted in order to understand the importance of PPARa in the feto-placental unit. 3.2 PPARª The critical importance of PPARg in the regulation of fetoplacental development was first demonstrated in the knockout mouse [4]. PPARg-deficient embryos had abnormal trophoblast differentiation as well as defective placental vasculature. Barak et al. reported a robust expression of PPARgd mRNA in the placenta from embryonic day 8.5 (E8.5) onwards [4]. This is lethal by E10, at the point when the primary responsibility for the maintenance of fetal metabolism is transferred from the yolk sac to the placenta [4, 67]. In addition, a complete absence of all types of adipose tissue in the mutant pups and severe defects of the heart were observed. Disruption of either PPAR-binding protein or PPAR-interacting protein also results in defective placental development and embryonic lethality due to defects in multiple organ systems [67–69]. In order to overcome the problem of embryonic lethality in PPARg null mice, cell-specific deletion of the gene using the Cre-loxP recombination system has been performed. While some cell types did not appear to be dependent on functional PPARg, the loss of the PPARg gene in oocytes and granulosa cells resulted in impaired fertility, featuring reduced progesterone levels and implantation rates [70]. PPARg is expressed in human placental tissues at various stages of gestation. PPARg mRNA was also present in all choriodecidual and villous human placental samples, and its level remained unaltered with the onset of labor [48]. PPARg protein was localized in the nuclei of the syncytiotrophoblast, cytotrophoblast and endothelial cells of the term human placenta. The placental choriocarcinoma cells (BeWo and JEG-3 cells) express PPARg, which is functionally responsive to 15-deoxy-D12,14-prostaglandin J2 (15d-PGJ2) [27, 48, 71, 72]. Implantation of the human conceptus involves invasion of the uterine epithelium and the underlying stroma by trophoblastic cells, which undergo a complex process involving proliferation, migration and differentiation. Trophoblast differentiation is modulated by PPARg, and its effects are reported to be ligand specific [73]. Troglitazone (a synthetic agonist of PPARg) stimulates PPARg activity www.ejlst.com Eur. J. Lipid Sci. Technol. 108 (2006) 70–83 in BeWo cells and enhances the biochemical and morphological differentiation of primary trophoblasts. In contrast, 15d-PGJ2 (endogenous agonist of PPARg) stimulates PPARg activity in BeWo cells, but reduces differentiation and increases apoptosis of human trophoblasts in culture [73]. A similar induction of apoptosis by 15dPGJ2 was observed in many carcinoma cell lines [74–76]. The mechanism of 15d-PGJ2-induced apoptosis is not clearly understood; however, an increased expression of apoptotic proteins (caspase 3, caspase 9, and Bax) and decreased expression of the anti-apoptotic protein Bcl-2 and the transcription factor NF-kB were observed in these cases [75, 77]. In vivo production of diverse PPARg ligands in the feto-placental unit may result in differential and perhaps opposing effects on trophoblast differentiation and apoptosis. PPARg ligands also inhibit extravillous cytotrophoblast invasion in vitro [26, 27, 78]. Both 15d-PGJ2 and rosiglitazone inhibited extravillous cytotrophoblast invasion in a concentration-dependent manner and in synergy with pan-RXR agonists. Both PPARg and pan-RXR antagonists were found to promote cytotrophoblast invasion in this model system [26, 27]. Subsequently, it was shown that other putative natural ligands for PPARg, such as oxidized low-density lipoproteins (oxLDL), also inhibited cytotrophoblast invasion [78]. These data indicate that PPARg may also play a role in human trophoblastic invasion, which, unlike tumor invasion, is precisely regulated. A defective invasion of the uterine spiral arteries is directly involved in preeclampsia. PPARg protein expression and activation are dramatically increased in a trophoblast cell line (JEG-3 cells) when incubated in the presence of serum lipids isolated from pregnant women [79]. In addition, PPARg-RXRa heterodimers have been shown to be important modulators of hormone synthesis in the human trophoblast [27, 73]. Activation of PPARg in these cells by rosiglitazone increased the levels of hCG, leptin, human placental lactogen and human growth hormone [27]. PPARg and RXRa ligands increase the hCGb transcript level; the hCGb promoter was suggested to contain binding sites for PPARg-RXRa heterodimers [27]. Several other endogenous PPARg ligands, such as 9S-hydroxy-10E,12S-octadecadienoic acid (9-HODE), 13S-hydroxy-9Z,11E-octadecadienoic acid (13-HODE), and 15S-hydroxy5Z,8Z,11Z,13E-eicosatetraenoic acid (15-HETE), stimulated hCG production in primary human trophoblasts [80]. This indicates a role for these oxygenated fatty acids and lipids in placental differentiation and function. Interestingly, no effect of these ligands on the expression of markers for syncytium formation (syncytin) or cell cycle progression was observed [80]. All these data warrant further research into the feto-placental synthesis of © 2006 WILEY-VCH Verlag GmbH & Co. KGaA, Weinheim PPARs and their roles in human placenta 73 diverse ligands in relation to PPARg activity, as this may affect pregnancies via cell differentiation and hormone synthesis in the feto-placental unit. The current hypothesis regarding the etiology of preeclampsia is focused on maladaptation of immune responses and defective trophoblast invasion. An excessive maternal inflammatory response perhaps results in a chain of events including shallow trophoblast invasion, defective spiral artery remodeling, placental infarction and release of pro-inflammatory cytokines and placental fragments into the systemic circulation. Several cytokines, produced at the maternal-fetal interface, have an impact on trophoblast invasion. Inflammation is associated with oxidative stress and enhanced expression of adhesion molecules and cytokines in the vasculature, resulting in the infiltration of neutrophils and monocytes/ macrophages [81]. PPARg ligands inhibit the activation of inflammatory gene expression and can negatively interfere with pro-inflammatory transcription factor signaling pathways in vascular and inflammatory cells [81]. Apart from trans-activating genes, a major role of PPARg is in the trans-suppression of inflammatory gene activation, by negatively interfering with the NF-kB, STAT-1, and AP-1 signaling pathways in a DNA binding-independent manner [82]. Several lines of evidence suggest that PPARg exerts anti-inflammatory effects by negatively regulating the expression of pro-inflammatory genes induced in response to macrophage differentiation and activation. An increased oxLDL uptake leads to the formation of foam cells in macrophages, a critical step for the development of atherosclerosis lesions; however, very little information is available with respect to placental trophoblast uptake of oxLDL and subsequent development of pathological states such as preeclampsia. The macrophage scavenger receptor CD36 (FAT) plays a key role in the initiation of atherosclerosis through its ability to bind to and internalize oxLDL. FAT/CD36 is also expressed on the cell surface trophoblasts [12], and therefore it may be involved in the uptake of oxLDL and can thus supply the necessary agonist for activation of PPARg and LXR in trophoblast cells (please see the LXR section). The multifunctional activities of CD36 in trophoblasts suggest that modulation of CD36 expression might lead to a series of potential beneficial or harmful effects in pregnancy. 3.3 PPAR PPARd, mRNA and protein, is expressed in human trophoblast cells [47, 83], but its function is still not fully known. Like PPARg, disruption of the PPARd gene in mice results in placental defects, and for more than 90% of fetuses it is lethal early in gestation (E10.5) [84]. Homozygous loss of PPARd resulted in frequent embryonic www.ejlst.com 74 A. K. Duttaroy lethality and revealed an abnormal gap in the placentaldecidual interface by E9.5, 1 day before onset of lethality. Three out of four PPARd null embryos that survived beyond E10.5 exhibited extensive maternal hemorrhages into the labyrinthine zone [84]. PPARd is therefore essential for feto-placental growth and development, but its roles appear to be quite different from PPARg in feto-placental growth and development. While PPARg appears to be required for differentiation of the placental labyrinth, PPARd seems to be more important for the normal development of the placental-decidual interface [4, 84]. A recent study indicates that the prostacyclin (PGI2) analogue carbaprostacyclin (cPGI2), a ligand of PPARd, reduced 11b-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase type 2 (11b-HSD2) activity as well as expression at both protein and mRNA levels in cultured human placental trophoblasts [85]. Placental 11b-HSD2 plays a pivotal role in controlling the precise levels of fetal exposure to maternal glucocorticoids and its modulation within the placenta [86]. An appropriate level of 11b-HSD2 in the human placenta appears to be critical for normal fetal development, because the reduced expression of this enzyme is associated with complicated pregnancies (such as IUGR). PPARd therefore may be involved in the regulation of placental function via 11b-HSD2. PPARd may also be involved in embryo implantation and decidualization [87]. Scherle et al. [88] have shown that activation of the p38 signaling cascade is required for the induction of cyclooxygenase (COX)-2 and PPARd expression during decidualization in the mouse. PPARd is markedly induced in the stroma surrounding the implanting blastocyst from the time when the attachment reaction occurs [89]. cPGI2 enhanced the heterodimerization of PPARd and RXRa within the decidual cell nucleus and induced transcription of a PPRE-containing reporter gene in a human endometrial cell line [87]. The maintenance of early pregnancy requires an intracrine prostanoid signaling pathway involving COX-2, PGI2 and PPARd [89]. Taken together, these results provide evidence that COX-2-derived PGI2 is involved in implantation and decidualization via activation of PPARd. All these data indicate that PPARd is a regulating factor for feto-placental growth and development. An abnormal activity of PPARd in the human placenta may lead to an altered expression of its target genes and thus may contribute to pathological pregnancies. Further research is required at the molecular level for definitive conclusions. Eur. J. Lipid Sci. Technol. 108 (2006) 70–83 to their target DNA sequences as heterodimers with the RXR to direct repeat four (DR-4)-type sequence motifs termed LXR-responsive elements. There are two known types: LXRa (NR1H3) and LXRb (NR1H2) [90]. LXRa and LXRb play a key role in regulating the transcription of multiple genes involved in bile acid and fatty acid synthesis, glucose metabolism, and sterol efflux [90]. LXRb is ubiquitously expressed in all tissues, whereas the expression of LXRa is predominantly restricted to tissues known to play important roles in lipid metabolism, such as liver, kidney, macrophages, small intestine, and adipose tissue [91]. Although sterol loading induces LXR target genes, neither cholesteryl esters nor free cholesterol can act as ligands for LXR and conversion to oxysterols is required for transcriptional activity. The endogenous ligands for both LXR are likely to be intermediates or end products of sterol metabolic pathways, such as 22(R)-hydroxycholesterol, 24(S),25-epoxycholesterol, 24(S)-hydroxycholesterol and 27-hydroxycholesterol [92]. ABCA1 and ABCG1 induction in macrophages, liver, intestine, neuronal cells, and Sertoli cells synergistically occurs with 9-cis retinoic acid as RXR agonist and the natural oxysterols 20-hydroxycholesterol, 22-hydroxycholesterol, 24-hydroxycholesterol, 24,25epoxycholesterol, and 27-hydroxycholesterol. 24-Hydroxycholesterol is very abundant in the brain and the liver, which also produces significant amounts of 22-hydroxycholesterol and 27-hydroxycholesterol. The oxysterols 20-hydroxycholesterol, 22-hydroxycholesterol, and 24,25-epoxycholesterol are not present in cholesterolloaded macrophages, rendering them unlikely to be natural ligands of LXR. In contrast, 27-hydroxycholesterol is the predominant oxysterol in the circulation, as well as in macrophage-derived foam cells from atherosclerotic lesions, directly linking this cholesterol metabolite to processes in atherogenesis. The LXR belong to a subclass of nuclear hormone receptors that form obligate heterodimers with RXR and are bound and activated by oxidized cholesterol [90]. LXR bind The LXR control the expression of several genes required for cholesterol metabolism, such as members of the ATPbinding cassette (ABC) transporters, and apolipoprotein E, CYP7A1 [93]. LXR also influence lipoprotein metabolism through the control of modifying enzymes such as lipoprotein lipase, cholesteryl ester transfer protein and phospholipids transfer protein. [94]. LXRa-deficient mice were devoid of the expression of a number of lipogenic genes, e.g. SREBP-1c, fatty acid synthase (FAS), stearoyl-CoA desaturase-1 (SCD-1) and acetyl-CoA carboxylase-a (ACC-a). FAS, SCD-1 and ACC-a are directly regulated by SREBP-1 [93]. Therefore, LXR are not only involved in sterol metabolism, but also in the general lipid metabolism. Recently, we demonstrated the presence of both LXRa and b in human primary trophoblasts and BeWo cells [95]. The LXR agonist tularic (T0901317) increased the lipid synthesis associated with an increased synthesis of lipogenic target genes, SREBP-1 © 2006 WILEY-VCH Verlag GmbH & Co. KGaA, Weinheim www.ejlst.com 3.4 LXR and SREBP in human placental trophoblasts Eur. J. Lipid Sci. Technol. 108 (2006) 70–83 and FAS, in BeWo cells [95]. SREBP-1 and -2 are separate gene products of approximately 125 kDa located in the membranes of the endoplasmic reticulum and the nuclear envelope [96]. The gene for SREBP-1 has two different transcription start sites that generate two mRNA and proteins: SREBP-1a and -1c. SREBP-1 and -2 are both detected in the placenta. Insulin is also known to act via SREBP-1c via augmenting the nuclear content of SREBP-1c, while LC-PUFA suppress the nuclear content through a post-transcriptional mechanism. The roles of SREBP-1c in placenta are still not elucidated. Although PUFA evidently decrease lipogenesis in adipose tissue, in an SREBP-dependent manner, one cannot yet determine the importance of this effect in relation to the effect of the maternal PUFA transport across the placenta. PPARs and their roles in human placenta 75 effect of PPARg-induced increase of hCG production [27] and thereby contributing to balancing the production of hCG during pregnancy. 4 Fatty acid uptake by the placenta: Roles of PPAR Like PPARa [64], activation of LXR reduced secretion of hCG in trophoblasts [95]. Although the mechanisms of LXR-mediated inhibition of hCG secretion in BeWo cells is not known at present, we can speculate that LXRa may have a regulatory role in trophoblasts, countervailing the Human fetal growth and development have a unique requirement for the supply of dietary lipids. Fetal brain and retina are very rich in ARA and DHA, and a sufficient supply of these LC-PUFA from the maternal plasma by the placenta during the last trimester of pregnancy is of great importance [16, 98]. Free fatty acid (FFA) is the mode of transport of fatty acids across the placenta [17, 99]. The presence of several membrane fatty acid transport proteins [fatty acid binding protein (FABP)pm, fatty acid translocase (FAT), fatty acid transport protein (FATP)] and cytoplasmic fatty acid-binding proteins [liver-type (LFABP) and heart-type (H-FABP)] in human placenta was demonstrated [17]. FAT and FATP are present in placental membranes, microvillous and basal membranes whereas p-FABPpm is only present in microvillous membranes [17] of trophoblasts [100]. Studies in different tissues suggested that these membrane proteins alone or in tandem might be involved in effective uptake of FFA [12, 99, 101]. Unlike p-FABPpm, other fatty acid transporters such as FAT/CD36 and FATP do not have any preference for LCPUFA [102]. Therefore, location of FAT and FATP on both sides of the bipolar placental cells may allow bi-directional flow of all types of FFA across the placenta, whereas the exclusive location of p-FABPpm on the maternal side may favor the unidirectional flow of maternal plasma LC-PUFA to the fetus (Fig. 2). In addition to these membrane transporters, cytoplasmic fatty acidbinding proteins (L-FABP and H-FABP) were also identified in human placenta [17]. As there are differences in binding affinity and capacity of these two FABP, their expression in the placental trophoblasts may indicate differential fatty acid transport and metabolism. The COX metabolites of ARA, such as prostaglandin (PG)E2, TxB2 and LTB4 do not bind L-FABP, whereas cyclopentenone PG, PGA1, PGA2, PGJ2, and D12-PGJ2, bind more avidly than oleic acid to L-FABP. PGD2, PGE2 and PGF2a are poor competitors, whereas PGE1 is intermediate [103– 106]. It has been demonstrated that L-FABP transports these ligands to PPAR through protein-protein interaction and thus may play an important role in gene expression [107, 108]. In addition, differential effects of FABP on fatty acid uptake and esterification were demonstrated using transfected mouse L-cell fibroblasts [109]. It is possible that these proteins have different roles in terms of intracellular trafficking of fatty acids in the placenta. Daoud et al. reported an increased expression of L-FABP and H- © 2006 WILEY-VCH Verlag GmbH & Co. KGaA, Weinheim www.ejlst.com Expression of LXRa was at higher levels in undifferentiated than in differentiated trophoblasts, while this was opposite in the case of LXRb expression [95]. In addition, LXRa but not LXRb mRNA expression was increased by T0901317 treatment in BeWo cells [95]. LXRb is involved in inhibitory effects of oxLDL on trophoblast invasion in vitro [97]; however, underlying mechanisms are not known yet. LXR may therefore play an important role in preeclampsia, a condition in which lipid peroxidation is increased and invasion of trophoblasts is reduced. The receptors (FAT/CD36) for oxLDL in trophoblasts may supply oxysterols through uptake of oxLDL for activation of LXR and thus may increase fatty acid synthesis. Fatty acid synthesized in the trophoblasts may then contribute to fetal or maternal plasma lipids. Hyperlipidemia is the most common complication of pregnancy and remains a source of maternal-child morbidity; however, the etiology of this disorder is still not understood. Maternal hyperlipidemia is a characteristic feature during pregnancy and corresponds to an accumulation of triglycerides not only in very-low-density lipoproteins (VLDL) but also in LDL and high-density lipoproteins (HDL). In preeclampsia, there is a further increase in plasma lipids compared with normal pregnancy. Maternal liver may play an important role in lipid homeostasis; however, a placental role in the development of hyperlipidemia has been increasingly evident. It is therefore highly likely that LXR-SREBP interaction may work in tandem in regulating lipid metabolism in the placenta. In fact, the simultaneous regulation of enzymes in both cholesterol and fatty acid synthesis pathways by LXR may allow coordinate regulation of overall lipid metabolism in the placenta. 76 A. K. Duttaroy Eur. J. Lipid Sci. Technol. 108 (2006) 70–83 Fig. 2. Schematic diagram of the putative roles of fatty acid binding/transporter proteins in human placental fatty acid uptake and metabolism. The presence of FAT and FATP on both sides of bipolar placental cell membranes allows transport of all sorts of fatty acids in both directions (from the mother to the fetus and vice versa). However, by virtue of its exclusive location on the maternal-facing placental membrane, p-FABPpm sequesters maternal plasma LC-PUFA to the placenta for fetal supply. Cytoplasmic FABP may be responsible for transcytoplasmic movement of FFA to their sites of esterification, b-oxidation, or induce gene expression by interacting with PPAR. FAT, fatty acid translocase; FATP, fatty acid transport protein; L-FABP, liver-type fatty acid-binding protein; H-FABP, heart-type fatty acid-binding protein. The tissue-specific regulation of FAT/CD36 and FATP expression by PPAR has been demonstrated, with hepatic expression of FAT, and FATP under the control of PPARa, whereas in adipose tissue these proteins are controlled by PPARg [11, 71, 110–113]. In contrast, it appears that FABPpm expression is not under control of PPARa and PPARg. Several naturally occurring ligands for PPARg have been identified, including fatty acids, oxLDL derivatives, and PG metabolites (15d-PGJ2). The potential natural ligands involved in activating PPAR/RXR heterodimers in the placenta are not yet known; however, it is possible that these ligands may activate expression of fatty acid binding/transport proteins in human placenta. Expression of p- FABPpm permits the placenta to recruit ARA and DHA which may also act as ligands for PPAR and RXR. The presence of FAT, FATP, L-FABP, and H-FABP in placental trophoblasts may help to deliver the ligands (fatty acid and eicosanoids) to PPARg for gene expression. Therefore, it is conceivable that natural ligands for PPAR are either synthesized or taken up by the trophoblast, enabling PPARRXR heterodimer activation, and this may lead to an increased fatty acid uptake. Schaiff et al. have reported recently that PPARg and RXR regulate fatty acid transport and storage in human placental trophoblasts [114]. They found that stimulation of trophoblast fatty acid uptake by ligand-activated PPARg and/or RXR was associated with enhanced expression of adipophilin and FATP-4 [114, 115]. Their data also suggested that RXR, most possibly in collaboration with other nuclear receptors, may predominantly regulate fatty acid transport in these cells. In fact, we have also observed similar increased fatty acid uptake © 2006 WILEY-VCH Verlag GmbH & Co. KGaA, Weinheim www.ejlst.com FABP in placental trophoblasts during differentiation, although the increased expression of these proteins was not associated with increased fatty acid uptake by these cells [71]. Eur. J. Lipid Sci. Technol. 108 (2006) 70–83 after incubating placental trophoblasts with DHA, which is a known ligand for RXR or PPAR (Tobin et al., unpublished observation). Further systematic studies are required using selective knockdown of these nuclear transcription factors as well as fatty acid transport/binding proteins, in order to determine the relative importance of these transcription factors and their relationships with the fatty acid transport system in the placenta. 5 Placental synthesis of ligands for PPAR Fatty acids have been involved in the proliferation and differentiation of numerous cells mediated via PPAR or their metabolites. The PPAR are a family of nuclear receptors activated by selected long-chain fatty acids and their oxygenated derivatives. In fact, PPARa was identified first as a transcription factor activated by a diverse class of compounds that cause proliferation of peroxisomes, including fatty acids and their metabolites [116]. In general, numerous naturally occurring fatty acids and ARA metabolites have been shown to be putative endogenous ligands for PPAR [87, 117, 118]. PPARs and their roles in human placenta 77 ligand to date, several other eicosanoids have been identified. Ferry et al. [126] identified PGH1 and PGH2 as ligands for PPARg, each having similar affinity to 15d-PGJ2 in both binding and subsequent transactivation assays. The role of a PG endoperoxide-PPAR signaling pathway in pregnancy is a strong possibility, although it is completely unknown. PGF2a is also produced by human placenta and is a known inhibitor of PPARg [127]. Implication of the interaction between PPARg and PGF2a in placental biology is not known. PGI2 and its synthetic analogues (cPGI2 and iloprost), which activate cell surface PGI2 receptors [128], have also been shown to bind and activate PPARd. Therefore, PGI2 can act via two different receptor signaling pathways to control cell metabolism, apparently depending on whether it is produced intracellularly or extracellularly [129]. The feto-placental unit synthesizes diverse eicosanoids and these may serve as putative ligands for PPAR and LXR in the placenta. In fact, PG concentrations in maternal plasma, amniotic fluid, and intra-uterine tissues increase in late human pregnancy [119]. PG are synthesized from ARA by the action of COX-1 or -2 and specific PG isomerases/synthases in human placenta [120, 121]. Once outside the cell, PG may bind to specific plasma membrane receptors to elicit a diverse range of biological responses [122, 123]. High concentrations of PGD2 have been reported in the human placenta, extra-placental membranes and amniotic fluid, with increased amniotic fluid levels at term compared to preterm [120, 121]. Detection and measurement of this PG has been complicated by the fact that PGD2 spontaneously converts into J-series PG, including PGJ2, D12-PGJ2 and 15d-PGJ2, in vitro. It has been speculated that 15d-PGJ2 and other PGJ2 derivatives may contribute to the mechanisms that underlie the rupture of gestational membranes at term or preterm [60, 124]. The pro-apoptotic effect of PGJ2 and its derivatives D12-PGJ2 and 15d-PGJ2 have previously been demonstrated in JEG-3 cells and amnion-like WISH cells, where apoptosis was shown to be caspase dependent and mimicked by the synthetic PPARg ligand, ciglitazone. However, there is increasing evidence that 15d-PGJ2 has nonPPARg-mediated effects in several cell systems. Despite intense investigation of the actions of 15d-PGJ2 in a variety of cell systems, conclusive evidence for its endogenous production and in vivo activity has been lacking until recently. Shibata et al. [125] have now demonstrated in vivo production of 15d-PGJ2 during inflammatory processes. Although 15d-PGJ2 is perhaps the most studied putative natural PPAR Lipoxygenase products of ARA and linoleate, the hydroxyeicosatetraenoic acids (HETE) and hydroxyoctadecadienoic acids (HODE), respectively, have been shown to activate PPAR. LTB4 is a downstream product of the 5-lipoxygenase (5-LO) pathway of ARA. 5-LO translocates to the nucleus where it associates with FLAP, and has the potential to generate a nuclear pool of leukotrienes [130, 131]. LTB4 has been reported to bind and activate PPARa with nanomolar affinity [132, 133]. Interestingly, several lipoxygenase metabolites of ARA (LTB4 and LTC4; 5-, 12-, and 15-HETE) are produced by gestational tissues and placental trophoblasts [121, 134–138] and may have a role in the onset of labor [134–139]. Amniotic fluid concentration of LTB4 was suggested as a possible marker for women with preterm labor [140]. A mixture of (S)-enantiomer HETE was shown to activate PPARa but had no effect on the other PPAR subtypes. Most of this activity was shown to be due to 8(S)-HETE and was stereoselective [141, 142], although less is known about the biological role of 8(S)-HETE compared to the more frequently studied 5-, 12-, and 15-HETE [140]. Several other oxidized fatty acids, including 9-HODE and 13-HODE, can activate PPARg and there is evidence to suggest that these endogenous PPARg ligands may be important regulators of gene expression in the feto-placental unit. All these diverse ligands for PPAR produced in the feto-placental unit can modulate the feto-placental unit through both PPAR and non-PPAR pathways and can affect the course of pregnancy. Although the nature of true endogenous PPAR ligands is still not known, PPAR can be activated by a wide variety of ‘endogenous’ or pharmacological ligands. Although fatty acids are generally considered as PPAR agonists, there have been considerable variations among published reports regarding the potency of different types of fatty acids and their oxygenated metabolites on the ligand-binding activity of PPAR and transactivation of PPRE. Tab. 1 summarizes the major endogenous ligands for PPAR. PPARá activators include a variety of endogen- © 2006 WILEY-VCH Verlag GmbH & Co. KGaA, Weinheim www.ejlst.com 78 A. K. Duttaroy Eur. J. Lipid Sci. Technol. 108 (2006) 70–83 ously present fatty acids, LTB4 and HETE, and clinically used drugs such as the fibrates, a class of first-line drugs in the treatment of dyslipidemia. Similarly, PPARg can be activated by a number of ligands, including DHA, linoleic acid, the anti-diabetic glitazones used as insulin sensitizers, and a number of lipids including oxLDL, azoyle-PAF, and eicosanoids such as 5,8,11,14-eicosatetraynoic acid and the prostanoids PGA1, PGA2, PGD2, and their dehydration products of the PGJ series of cyclopentanones. 6 Conclusions Emerging evidence indicates that PPAR, LXR, and SREBP-1c play very important and complex roles in placental biology. The biological responses initiated by these receptors depend on their activation by liganddependent or -independent pathways as well as the cross-talk with each other and their response elements, as well as several transcription factors. It is therefore possible that these nuclear transcription factors (PPAR, SREBP, and LXR), either alone or in tandem, control fetoplacental growth and development. Tab. 2 shows the interaction and function of these transcription factors in human placenta. Since these receptors are fatty acid sensors, their expression in the placenta may also be regulated by the flux of fatty acids in the feto-placental unit. It is important to note that placental uptake of fatty acids and their metabolism (b-oxidation) are not regulated by insulin or leptin as in the case of adipose or other tissues [143]. Tab. 1. Fatty acids and their oxygenated derivative ligands of PPAR. Major endogenous ligands PPARÆ PPAR PPARª Palmitic acid, 16:0 Stearic acid, 18:0 Palmitoleic acid, 16:1n-7 Oleic acid, 18:1n-9 Linoleic acid, 18:2n-6 Arachidonic acid, 20:4n-6 Eicosapentaenoic acid, 20:5n-3 Docosahexanenoic acid, 22:6n-3 LTB4 Fatty acids Prostacyclin Arachidonic acid, 20:4n-6 15d-PGJ2 9-HODE 13-HODE 15-HETE Linoleic acid Arachidonic acid, 20:4n-6 Docosahexaenoic acid, 22:6n-3 Docosahexaenoic acid, 22:6n-3 Tab. 2. Role of nuclear transcription factors in placental trophoblasts. PPARÆ PPAR PPARª LXR SREBP–1c Cell growth Inhibits cell growth Stimulates cell growth Depends on ligands Stimulates cell growth Not known Apoptosis/ differentiation Not known Increases differentiation Depends on ligands Increases differentiation Not known Critical for fetoplacental growth and development Not essential Critically essential Critically essential Not essential Not known hCG secretion Decreases hCG secretion Not known Increases hCG secretion Decreases hCG secretion Not known Trophoblast invasion Not known Not known Inhibits invasion Inhibits invasion Not known Lipid metabolism Not known Increases fatty acid uptake Increases fatty acid uptake Increases fatty acid synthesis via FAS and SREBP-1 expression Increases fatty acid synthesis © 2006 WILEY-VCH Verlag GmbH & Co. KGaA, Weinheim www.ejlst.com Eur. J. Lipid Sci. Technol. 108 (2006) 70–83 Maternal LC-PUFA taken up by the placenta may also act as ligands for these receptors and modulate the placental biology. A recent study by Waite et al. reported that circulating activators of PPAR are reduced in preeclamptic pregnant women’s sera [144]. The reduction was much more prominent for PPARg than for PPARa activation. The endogenous factors in the maternal plasma may play a role in lipid metabolism and immune function in the feto-placental unit as seen in preeclampsia. LTB4, saturated and monounsaturated fatty acids are ligands for PPARa, whereas oxygenated fatty acids (9-HODE, 13-HODE, and 15-HETE) and 15d-PGJ2 are PPARg ligands. Identification of circulating ligands and their interactions with the nuclear transcription factors in the feto-placental unit may be an important aspect of future research in this area. Better understanding of these transcription factors and their ligands in the feto-placental unit possibly gives us clues to prevent maternal, fetal and adult diseases associated with placental dysfunction. Acknowledgment This work has been supported by the grant Throne Holst Foundation, Norway. References [1] N. M. Gude, C. T. Roberts, B. Kalionis, R. G. King: Growth and function of the normal human placenta. Thromb Res. 2004, 114, 397–407. [2] A. K. Duttaroy: Fatty acid transport and metabolism in the feto-placental unit and the role of fatty acid-binding proteins. J Nutr Biochem. 1997, 8, 548–557. [3] K. K. Ong, D. B. Dunger: Perinatal growth failure: The road to obesity, insulin resistance and cardiovascular disease in adults. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2002, 16, 191– 207. [4] Y. Barak, M. C. Nelson, E. S. Ong, Y. Z. Jones, P. Ruiz-Lozano, K. R. Chien, A. Koder, R. M. Evans: PPAR gamma is required for placental, cardiac, and adipose tissue development. Mol Cell. 1999, 4, 585–595. [5] E. B. Berry, R. Eykholt, R. J. Helliwell, R. S. Gilmour, M. D. Mitchell, K. W. Marvin: Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor isoform expression changes in human gestational tissues with labor at term. Mol Pharmacol. 2003, 64, 1586– 1590. [6] N. Z. Ding, C. B. Teng, H. Ma, H. Ni, X. H. Ma, L. B. Xu, Z. M. Yang: Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor delta expression and regulation in mouse uterus during embryo implantation and decidualization. Mol Reprod Dev. 2003, 66, 218–224. [7] Y. Xu, T. J. Cook, G. T. Knipp: Effects of di-(2-ethylhexyl)phthalate (DEHP) and its metabolites on fatty acid homeostasis regulating proteins in rat placental HRP-1 trophoblast cells. Toxicol Sci. 2005, 84, 287–300. [8] M. V. Chakravarthy, Z. J. Pan, Y. M. Zhu, K. Tordjman, J. G. Schneider, T. Coleman, J. Turk, C. F. Semenkovich: “New” hepatic fat activates PPAR alpha to maintain glucose, lipid, and cholesterol homeostasis. Cell Metab. 2005 1, 309–322. © 2006 WILEY-VCH Verlag GmbH & Co. KGaA, Weinheim PPARs and their roles in human placenta 79 [9] H. Glosli, O. A. Gudbrandsen, A. J. Mullen, B. Halvorsen, T. H. Rost, H. Wergedahl, H. Prydz, P. Aukrust, R. K. Berge: Down-regulated expression of PPAR alpha target genes, reduced fatty acid oxidation and altered fatty acid composition in the liver of mice transgenic for hTNF alpha. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2005, 1734, 235–246. [10] C. Hohberg, G. Lubben, T. Forst, N. Marx, M. M. Weber, M. Lobig, A. Pfutzner: PPAR gamma stimulation improves cardiovascular risk profile independent from its glucose lowering effects. Diabetes. 2005, 54, A149–A150. [11] S. Luquet, C. Gaudel, D. Holst, J. Lopez-Soriano, C. JehlPietri, A. Fredenrich, P. A. Grimaldi: Roles of PPAR delta in lipid absorption and metabolism: A new target for the treatment of type 2 diabetes. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2005, 1740, 313–317. [12] A. K. Duttaroy: Transport mechanisms for long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acids in the human placenta. Am J Clin Nutr. 2000, 71, 315S–322S. [13] P. Haggarty: Effect of placental function on fatty acid requirements during pregnancy. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2004, 58, 1559–1570. [14] S. M. Innis: Essential fatty acids in growth and development. Prog Lipid Res. 1991, 30, 39–103. [15] S. M. Innis: The role of dietary n-6 and n-3 fatty acids in the developing brain. Dev Neurosci. 2000, 22, 474–480. [16] S. M. Innis: Essential fatty acid transfer and fetal development. Placenta. 2005, 26 SupplA, S70–S75. [17] F. M. Campbell, P. G. Bush, J. H. Veerkamp, A. K. Duttaroy: Detection and cellular localization of plasma membraneassociated and cytoplasmic fatty acid-binding proteins in human placenta. Placenta. 1998, 19, 409–415. [18] B. I. Frohnert, T. Y. Hui, D. A. Bernlohr: Identification of a functional peroxisome proliferator-responsive element in the murine fatty acid transport protein gene. J Biol Chem. 1999, 274, 3970–3977. [19] N. M. Lapsys, A. D. Kriketos, M. Lim-Fraser, A. M. Poynten, A. Lowy, S. M. Furler, D. J. Chisholm, G. J. Cooney: Expression of genes involved in lipid metabolism correlate with peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma expression in human skeletal muscle. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2000, 85, 4293–4297. [20] G. Martin, K. Schoonjans, A. M. Lefebvre, B. Staels, J. Auwerx: Coordinate regulation of the expression of the fatty acid transport protein and acyl-CoA synthetase genes by PPAR alpha and PPAR gamma activators. J Biol Chem. 1997, 272, 28210–28217. [21] K. Motojima, P. Passilly, J. M. Peters, F. J. Gonzalez, N. Latruffe: Expression of putative fatty acid transporter genes are regulated by peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor alpha and gamma activators in a tissue- and inducer-specific manner. J Biol Chem. 1998, 273, 16710–16714. [22] K. Schoonjans, B. Staels, J. Auwerx: The peroxisome proliferator activated receptors (PPARs) and their effects on lipid metabolism and adipocyte differentiation. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1996, 1302, 93–109. [23] S. D. Clarke: Polyunsaturated fatty acid regulation of gene transcription: A molecular mechanism to improve the metabolic syndrome. J Nutr. 2001, 131, 1129–1132. [24] D. B. Jump: Fatty acid regulation of gene transcription. Crit Rev Clin Lab Sci. 2004, 41, 41–78. [25] A. K. Duttaroy: Fetal growth and development: Roles of fatty acid transport proteins and nuclear transcription factors in human placenta. Indian J Exp Biol. 2004, 42, 747–757. [26] T. Fournier, L. Pavan, A. Tarrade, K. Schoonjans, J. Auwerx, C. Rochette-Egly, D. Evain-Brion: The role of PPAR-gamma/ www.ejlst.com 80 A. K. Duttaroy RXR-alpha heterodimers in the regulation of human trophoblast invasion. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2002, 973, 26–30. [27] A. Tarrade, K. Schoonjans, J. Guibourdenche, J. M. Bidart, M. Vidaud, J. Auwerx, C. Rochette-Egly, D. Evain-Brion: PPAR gamma/RXR alpha heterodimers are involved in human CG beta synthesis and human trophoblast differentiation. Endocrinology. 2001, 142, 4504–4514. [28 A. Chawla, J. J. Repa, R. M. Evans, D. J. Mangelsdor: Nuclear receptors and lipid physiology: Opening the X-files. Science. 2001, 294, 1866–1870. [29] J. D. Chen, R. M. Evans: A transcriptional co-repressor that interacts with nuclear hormone receptors. Nature. 1995, 377, 454–457. [30] A. J. Horlein, A. M. Naar, T. Heinzel, J. Torchia, B. Gloss, R. Kurokawa, A. Ryan, Y. Kamei, M. Soderstrom, C. K. Glass: Ligand-independent repression by the thyroid hormone receptor mediated by a nuclear receptor co-repressor. Nature 1995, 377, 397–404. [31] M. Hadzopoulou-Cladaras, E. Kistanova, C. Evagelopoulou, S. Zeng, C. Cladaras, J. A. Ladias: Functional domains of the nuclear receptor hepatocyte nuclear factor 4. J Biol Chem. 1997, 272, 539–550. [32] M. D. Ruse, Jr., M. L. Privalsky, F. M. Sladek: Competitive cofactor recruitment by orphan receptor hepatocyte nuclear factor 4alpha1: Modulation by the F domain. Mol Cell Biol. 2002, 22, 1626–1638. [33] B. D. Darimont, R. L. Wagner, J. W. Apriletti, M. R. Stallcup, P. J. Kushner, J. D. Baxter, R. J. Fletterick, K. R. Yamamoto: Structure and specificity of nuclear receptor-coactivator interactions. Genes Dev. 1998, 12, 3343–3356. [34] R. Kurokawa, M. Soderstrom, A. Horlein, S. Halachmi, M. Brown, M. G. Rosenfeld, C. K. Glass: Polarity-specific activities of retinoic acid receptors determined by a corepressor. Nature. 1995, 377, 451–454. [35] E. Hu, J. B. Kim, P. Sarraf, B. M. Spiegelman: Inhibition of adipogenesis through MAP kinase-mediated phosphorylation of PPARgamma. Science. 1996, 274, 2100–2103. [36] E. Soutoglou, N. Katrakili, I. Talianidis: Acetylation regulates transcription factor activity at multiple levels. Mol Cell. 2000, 5, 745–751. [37] M. G. Rosenfeld, C. K. Glass: Coregulator codes of transcriptional regulation by nuclear receptors. J Biol Chem. 2001, 276, 36865–36868. [38] T. Jenuwein, C. D. Allis: Translating the histone code. Science. 2001, 293, 1074–1080. [39] F. M. Gregoire, V. Rakhmanova, F. Zhang, Y. Zhu, J. Y. Ma, P. Cheng, S. Zhao, B. Lavan, T. A. Gustafson: Effects of novel PPAR delta, PPAR dual delta/gamma and PPAR delta/ gamma/alpha (pan (TM)) agonists on PPAR-responsive genes in human adipocytes and macrophages. Diabetes. 2005, 54, A140. [40] T. Lemberger, R. Saladin, M. Vazquez, F. Assimacopoulos, B. Staels, B. Desvergne, W. Wahli, J. Auwerx: Expression of the peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor alpha gene is stimulated by stress and follows a diurnal rhythm. J Biol Chem. 1996, 271, 1764–1769. [41] O. Braissant, F. Foufelle, C. Scotto, M. Dauca, W. Wahli: Differential expression of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors (PPARs): Tissue distribution of PPAR-alpha, -beta, and -gamma in the adult rat. Endocrinology. 1996, 137, 354– 366. [42] T. E. Cullingford, K. Bhakoo, S. Peuchen, C. T. Dolphin, R. Patel, J. B. Clark: Distribution of mRNAs encoding the peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor alpha, beta, and gamma and the retinoid X receptor alpha, beta, and gamma in rat central nervous system. J Neurochem. 1998, 70, 1366–1375. © 2006 WILEY-VCH Verlag GmbH & Co. KGaA, Weinheim Eur. J. Lipid Sci. Technol. 108 (2006) 70–83 [43] S. A. Kliewer, B. M. Forman, B. Blumberg, E. S. Ong, U. Borgmeyer, D. J. Mangelsdorf, K. Umesono, R. M. Evans: Differential expression and activation of a family of murine peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994, 91, 7355–7359. [44] T. Lemberger, O. Braissant, C. Juge-Aubry, H. Keller, R. Saladin, B. Staels, J. Auwerx, A. G. Burger, C. A. Meier, W. Wahli: PPAR tissue distribution and interactions with other hormone-signaling pathways. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1996, 804, 231–251. [45] A. V. Ershov, N. G. Bazan: Photoreceptor phagocytosis selectively activates PPARgamma expression in retinal pigment epithelial cells. J Neurosci Res. 2000, 60, 328–337. [46] D. Auboeuf, J. Rieusset, L. Fajas, P. Vallier, V. Frering, J. P. Riou, B. Staels, J. Auwerx, M. Laville, H. Vidal: Tissue distribution and quantification of the expression of mRNAs of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors and liver X receptor-alpha in humans: No alteration in adipose tissue of obese and NIDDM patients. Diabetes. 1997, 46, 1319–1327. [47] R. Mukherjee, L. Jow, G. E. Croston and J. R. Paterniti, Jr.: Identification, characterization, and tissue distribution of human peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor (PPAR) isoforms PPARgamma2 versus PPARgamma1 and activation with retinoid X receptor agonists and antagonists. J Biol Chem. 1997, 272, 8071–8076. [48] K. W. Marvin, R. L. Eykholt, J. A. Keelan, T. A. Sato, M. D. Mitchell: The 15-deoxy-delta(12,14)-prostaglandin J(2)receptor, peroxisome proliferator activated receptorgamma (PPARgamma) is expressed in human gestational tissues and is functionally active in JEG3 choriocarcinoma cells. Placenta. 2000, 21, 436–440. [49] P. Tontonoz, E. Hu, B. M. Spiegelman: Stimulation of adipogenesis in fibroblasts by PPAR gamma 2, a lipid-activated transcription factor. Cell 1994, 79, 1147–1156. [50] P. Tontonoz, E. Hu, R. A. Graves, A. I. Budavari, B. M. Spiegelman: PPAR gamma 2: Tissue-specific regulator of an adipocyte enhancer. Genes Dev. 1994, 8, 1224–1234. [51] P. Escher, W. Wahli: Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors: Insight into multiple cellular functions. Mutat Res. 2000, 448, 121–138. [52] L. Fajas, D. Auboeuf, E. Raspe, K. Schoonjans, A. M. Lefebvre, R. Saladin, J. Najib, M. Laville, J. C. Fruchart, S. Deeb, A. Vidal-Puig, J. Flier, M. R. Briggs, B. Staels, H. Vidal, J. Auwerx: The organization, promoter analysis, and expression of the human PPARgamma gene. J Biol Chem. 1997, 272, 18779–18789. [53] L. Fajas, J. C. Fruchart, J. Auwerx: PPARgamma3 mRNA: A distinct PPARgamma mRNA subtype transcribed from an independent promoter. FEBS Lett. 1998, 438, 55–60. [54] J. Vamecq, N. Latruffe: Medical significance of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors. Lancet. 1999, 354, 141– 148. [55] C. N. Palmer, M. H. Hsu, A. S. Muerhoff, K. J. Griffin, E. F. Johnson: Interaction of the peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor alpha with the retinoid X receptor alpha unmasks a cryptic peroxisome proliferator response element that overlaps an ARP-1-binding site in the CYP4A6 promoter. J Biol Chem. 1994, 269, 18083–18089. [56] C. N. Palmer, M. H. Hsu, H. J. Griffin, E. F. Johnson: Novel sequence determinants in peroxisome proliferator signaling. J Biol Chem. 1995, 270, 16114–16121. [57] P. Targett-Adams, M. J. McElwee, E. Ehrenborg, M. C. Gustafsson, C. N. Palmer, J. McLauchlan: A PPAR response element regulates transcription of the gene for human adipose differentiation-related protein. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2005, 1728, 95–104. www.ejlst.com Eur. J. Lipid Sci. Technol. 108 (2006) 70–83 [58] J. C. Corton, S. P. Anderson, A. Stauber: Central role of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors in the actions of peroxisome proliferators. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 2000, 40, 491–518. [59] O. Wendling, P. Chambon, M. Mark: Retinoid X receptors are essential for early mouse development and placentogenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999, 96, 547–551. [60] J. Keelan, R. Helliwell, B. Nijmeijer, E. Berry, T. Sato, K. Marvin, M. Mitchell, R. Gilmour: 15-Deoxy-delta12,14-prostaglandin J2-induced apoptosis in amnion-like WISH cells. Prostaglandins Lipid Mediat. 2001, 66, 265–282. [61] Q. Wang, D. Herrera-Ruiz, A. S. Mathis, T. J. Cook, R. K. Bhardwaj, G. T. Knipp: Expression of PPAR, RXR isoforms and fatty acid transporting proteins in the rat and human gastrointestinal tracts. J Pharm Sci. 2005, 94, 363–372. [62] S. S. Lee, T. Pineau, J. Drago, E. J. Lee, J. W. Owens, D. L. Kroetz, P. M. Fernandez-Salguero, H. Westphal, F. J. Gonzalez: Targeted disruption of the alpha isoform of the peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gene in mice results in abolishment of the pleiotropic effects of peroxisome proliferators. Mol Cell Biol. 1995, 15, 3012–3022. [63] H. Matsuo, J. F. Strauss, III: Peroxisome proliferators and retinoids affect JEG-3 choriocarcinoma cell function. Endocrinology. 1994, 135, 1135–1145. [64] F. Hashimoto, Y. Oguchi, M. Morita, K. Matsuoka, S. Takeda, M. Kimura, H. Hayashi: PPARalpha agonists clofibrate and gemfibrozil inhibit cell growth, down-regulate hCG and upregulate progesterone secretions in immortalized human trophoblast cells. Biochem Pharmacol. 2004, 68, 313–321. [65] K. Hanley, Y. Jiang, D. Crumrine, N. M. Bass, R. Appel, P. M. Elias, M. L. Williams, K. R. Feingold: Activators of the nuclear hormone receptors PPARalpha and FXR accelerate the development of the fetal epidermal permeability barrier. J Clin Invest. 1997, 100, 705–712. [66] M. Schmuth, K. Schoonjans, Q. C. Yu, J. W. Fluhr, D. Crumrine, J. P. Hachem, P. Lau, J. Auwerx, P. M. Elias, K. R. Feingold: Role of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor alpha in epidermal development in utero. J Invest Dermatol. 2002, 119, 1298–1303. [67] N. Kubota, Y. Terauchi, H. Miki, H. Tamemoto, T. Yamauchi, K. Komeda, S. Satoh, R. Nakano, C. Ishii, T. Sugiyama, K. Eto, Y. Tsubamoto, A. Okuno, K. Murakami, H. Sekihara, G. Hasegawa, M. Naito, Y. Toyoshima, S. Tanaka, K. Shiota, T. Kitamura, T. Fujita, O. Ezaki, S. Aizawa, T. Kadowaki: PPAR gamma mediates high-fat diet-induced adipocyte hypertrophy and insulin resistance. Mol Cell. 1999, 4, 597–609. [68] S. E. Crawford, C. Qi, P. Misra, V. Stellmach, M. S. Rao, J. D. Engel, Y. Zhu, K. Reddy: Defects of the heart, eye, and megakaryocytes in peroxisome proliferator activator receptor-binding protein (PBP) null embryos implicate GATA family of transcription factors. J Biol Chem. 2002, 277, 3585–3592. [69] Y. J. Zhu, S. E. Crawford, V. Stellmach, R. S. Dwivedi, M. S. Rao, F. J. Gonzalez, C. Qi, J. K. Reddy: Coactivator PRIP, the peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-interacting protein, is a modulator of placental, cardiac, hepatic, and embryonic development. J Biol Chem. 2003, 278, 1986– 1990. [70] Y. Cui, K. Miyoshi, E. Claudio, U. K. Siebenlist, F. J. Gonzalez, J. Flaws, K. U. Wagner, L. Hennighausen: Loss of the peroxisome proliferation-activated receptor gamma (PPARgamma) does not affect mammary development and propensity for tumor formation but leads to reduced fertility. J Biol Chem. 2002, 277, 17830–17835. [71] G. G. Daoud, L. Simoneau, A. Masse, E. Rassart, J. Lafond: Expression of cFABP and PPAR in trophoblast cells: Effect of PPAR ligands on linoleic acid uptake and differentiation. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2005, 1687, 181–194. © 2006 WILEY-VCH Verlag GmbH & Co. KGaA, Weinheim PPARs and their roles in human placenta 81 [72] A. K. Duttaroy, D. Crozet, J. Taylor, M. J. Gordon: Acyl-CoA thioesterase activity in human placental choriocarcinoma (BeWo) cells: Effects of fatty acids. Prostaglandins Leukot Essent Fatty Acids. 2003, 68, 43–48. [73] W. T. Schaiff, M. G. Carlson, S. D. Smith, R. Levy, D. M. Nelson, Y. Sadovsky: Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma modulates differentiation of human trophoblast in a ligand-specific manner. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2000, 85, 3874–3881. [74] J. H. Lee, H. S. Kim, S. Y. Jeong, I. K. Kim: Induction of p53 and apoptosis by delta 12-PGJ2 in human hepatocarcinoma SK-HEP-1 cells. FEBS Lett. 1995, 368, 348–352. [75] G. Eibl, M. N. Wente, H. A. Reber, O. J. Hines: Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma induces pancreatic cancer cell apoptosis. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2001, 287, 522–529. [76] Y. Tsubouchi, H. Sano, Y. Kawahito, S. Mukai, R. Yamada, M. Kohno, K. Inoue, T. Hla, M. Kondo: Inhibition of human lung cancer cell growth by the peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma agonists through induction of apoptosis. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2000, 270, 400–405. [77] E. J. Kim, K. S. Park, S. Y. Chung, Y. Y. Sheen, D. C. Moon, Y. S. Song, K. S. Kim, S. Song, Y. P. Yun, M. K. Lee, K. W. Oh, D. Y. Yoon, J. T. Hong: Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma activator 15-deoxy-Delta12,14-prostaglandin J2 inhibits neuroblastoma cell growth through induction of apoptosis: Association with extracellular signalregulated kinase signal pathway. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2003, 307, 505–517. [78] D. Evain-Brion, T. Fournier, P. Therond, A. Tarrade, L. Pavan: Pathogenesis of pre-eclampsia: Role of gamma PPAR in trophoblast invasion. Bull Acad Natl Med. 2002, 186, 409– 418. [79] L. L. Waite, E. C. Person, Y. Zhou, K. H. Lim, T. S. Scanlan, R. N. Taylor: Placental peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma is up-regulated by pregnancy serum. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2000, 85, 3808–3814. [80] R. L. Schild, W. T. Schaiff, M. G. Carlson, E. J. Cronbach, D. M. Nelson, Y. Sadovsky: The activity of PPAR gamma in primary human trophoblasts is enhanced by oxidized lipids. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2002, 87, 1105–1110. [81] L. A. Moraes, L. Piqueras, D. Bishop-Bailey: Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors and inflammation. Pharmacol Ther. 2005 (epub). [82] B. Staels, W. Koenig, A. Habib, R. Merval, M. Lebret, I. P. Torra, P. Delerive, A. Fadel, G. Chinetti, J. C. Fruchart, J. Najib, J. Maclouf, A. Tedgui: Activation of human aortic smooth-muscle cells is inhibited by PPARalpha but not by PPARgamma activators. Nature. 1998, 393, 790–793. [83] Q. Wang, H. Fujii, G. T. Knipp: Expression of PPAR and RXR isoforms in the developing rat and human term placentas. Placenta. 2002, 23, 661–671. [84] Y. Barak, D. Liao, W. He, E. S. Ong, M. C. Nelson, J. M. Olefsky, R. Boland, R. M. Evans: Effects of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor delta on placentation, adiposity, and colorectal cancer. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002, 99, 303–308. [85] L. Julan, H. Guan, J. P. van Beek, K. Yang: Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor delta suppresses 11beta-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase type 2 gene expression in human placental trophoblast cells. Endocrinology. 2005, 146, 1482– 1490. [86] K. Yang: Placental 11 beta-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase: Barrier to maternal glucocorticoids. Rev Reprod. 1997, 2, 129–132. www.ejlst.com 82 A. K. Duttaroy [87] H. Lim, S. K. Dey: PPAR delta functions as a prostacyclin receptor in blastocyst implantation. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2000, 11, 137–142. [88] P. A. Scherle, W. Ma, H. Lim, S. K. Dey, J. M. Trzaskos: Regulation of cyclooxygenase-2 induction in the mouse uterus during decidualization. An event of early pregnancy. J Biol Chem. 2000, 275, 37086–37092. [89] R. J. Helliwell, E. B. Berry, S. J. O’Carroll, M. D. Mitchell: Nuclear prostaglandin receptors: Role in pregnancy and parturition? Prostaglandins Leukot Essent Fatty Acids. 2004, 70, 149–165. [90] C. C. Song, R. A. Hiipakka, S. Liao: Selective activation of liver X receptor alpha by 6alpha-hydroxy bile acids and analogs. Steroids. 2000, 65, 423–427. [91] P. J. Willy, K. Umesono, E. S. Ong, R. M. Evans, R. A. Heyman, D. J. Mangelsdorf: LXR, a nuclear receptor that defines a distinct retinoid response pathway. Genes Dev. 1995, 9, 1033–1045. [92] J. M. Lehmann, S. A. Kliewer, L. B. Moore, T. A. Smith-Oliver, B. B. Oliver, J. L. Su, S. S. Sundseth, D. A. Winegar, D. E. Blanchard, T. A. Spencer, T. M. Willson: Activation of the nuclear receptor LXR by oxysterols defines a new hormone response pathway. J Biol Chem. 1997, 272, 3137–3140. [93] S. M. Ulven, H. I. Nebb: Liver X receptors (LXRs): Important regulators of lipid homeostasis. In: Cellular Proteins and Their Fatty Acids in Health and Disease. Eds. A. K. Duttaroy, F. Spener, VCH-Wiley, Weinheim (Germany) 2003, pp. 209– 220. [94] A. Venkateswaran, B. A. Laffitte, S. B. Joseph, P. A. Mak, D. C. Wilpitz, P. A. Edwards, P. Tontonoz: Control of cellular cholesterol efflux by the nuclear oxysterol receptor LXR alpha. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000, 97, 12097–12102. [95] M. S. Weedon-Fekjaer, A. K. Duttaroy, H. I. Nebb: Liver X receptors mediate inhibition of hCG secretion in a human placental trophoblast cell line. Placenta. 2005, 26, 721– 728. [96] H. Shimano: Sterol regulatory element-binding proteins (SREBPs): Transcriptional regulators of lipid synthetic genes. Prog Lipid Res. 2001, 40, 439–452. [97] L. Pavan, A. Hermouet, V. Tsatsaris, P. Therond, T. Sawamura, D. Evain-Brion, T. Fournier: Lipids from oxidized lowdensity lipoprotein modulate human trophoblast invasion: Involvement of nuclear liver X receptors. Endocrinology. 2004, 145, 4583–4591. [98] P. Haggarty: Placental regulation of fatty acid delivery and its effect on fetal growth – a review. Placenta. 2002, 23 Suppl A, S28–S38. [99] A. K. Duttaroy: Cellular uptake of long-chain fatty acids: Role of membrane-associated fatty-acid-binding/transport proteins. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2000, 57, 1360–1372. [100] F. M. Campbell, A. K. Duttaroy: Plasma-membrane fattyacid-binding protein (FABPpm)) is exclusively located in the maternal facing membranes of the human placenta. FEBS Lett. 1995, 375, 227–230. [101] J. F. C. Glatz, J. J. F. P. Luiken, A. Bonen: Involvement of membrane-associated proteins in the acute regulation of cellular fatty acid uptake. J Mol Neurosci. 2001, 16, 123– 132. [102] F. M. Campbell, M. J. Gordon, A. K. Duttaroy, Preferential uptake of long chain polyunsaturated fatty acids by isolated human placental membranes. Mol Cell Biochem. 1996, 155, 77–83. [103] A. K. Duttaroy, N. Gopalswamy, D. V. Trulzsch: Prostaglandin-E1 binds to Z-protein of rat liver. Eur J Biochem. 1987, 162, 615–619. © 2006 WILEY-VCH Verlag GmbH & Co. KGaA, Weinheim Eur. J. Lipid Sci. Technol. 108 (2006) 70–83 [104] R. A. Peeters, M. A. in ’t Groen, M. P. de Moel, H. T. van Moerkerk, J. H. Veerkamp: The binding affinity of fatty acidbinding proteins from human, pig and rat liver for different fluorescent fatty acids and other ligands. Int J Biochem. 1989, 21, 407–418. [105] J. H. Veerkamp, H. T. van Moerkerk, C. F. Prinsen, T. H. van Kuppevelt: Structural and functional studies on different human FABP types. Mol Cell Biochem. 1999, 192, 137– 142. [106] A. W. Zimmerman, H. T. van Moerkerk, J. H. Veerkamp: Ligand specificity and conformational stability of human fatty acid-binding proteins. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2001, 33, 865–876. [107] C. Wolfrum, T. Borchers, J. C. Sacchettini, F. Spener: Binding of fatty acids and peroxisome proliferators to orthologous fatty acid binding proteins from human, murine, and bovine liver. Biochemistry. 2000, 39, 14363– 14370. [108] C. Wolfrum, C. M. Borrmann, T. Borchers, F. Spener: Fatty acids and hypolipidemic drugs regulate peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors alpha – and gamma-mediated gene expression via liver fatty acid binding protein: A signaling path to the nucleus. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001, 98, 2323–2328. [109] E. J. Murphy, D. R. Prows, J. R. Jefferson, F. Schroeder: Liver fatty acid-binding protein expression in transfected fibroblasts stimulates fatty acid uptake and metabolism. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1996, 1301, 191–198. [110] J. C. Fruchart, P. Duriez, B. Staels: Peroxisome proliferatoractivated receptor-alpha activators regulate genes governing lipoprotein metabolism, vascular inflammation and atherosclerosis. Curr Opin Lipidol. 1999, 10, 245–257. [111] B. D. Hegarty, S. M. Furler, N. D. Oakes, E. W. Kraegen, G. J. Cooney: Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor (PPAR) activation induces tissue-specific effects on fatty acid uptake and metabolism in vivo – a study using the novel PPARalpha/gamma agonist tesaglitazar. Endocrinology. 2004, 145, 3158–3164. [112] B. Staels, J. Dallongeville, J. Auwerx, K. Schoonjans, E. Leitersdorf, J. C. Fruchart: Mechanism of action of fibrates on lipid and lipoprotein metabolism. Circulation. 1998, 98, 2088–2093. [113] Y. Tamori, J. Masugi, N. Nishino, M. Kasuga: Role of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma in maintenance of the characteristics of mature 3T3-L1 adipocytes. Diabetes. 2002, 51, 2045–2055. [114] W. T. Schaiff, I. Bildirici, M. Cheong, P. L. Chern, D. M. Nelson, Y. Sadovsky: Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma and retinoid X receptor signaling regulate fatty acid uptake by primary human placental trophoblasts. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2005, 90, 4267–4275. [115] I. Bildirici, C. R. Roh, W. T. Schaiff, B. M. Lewkowski, D. M. Nelson, Y. Sadovsky: The lipid droplet-associated protein adipophilin is expressed in human trophoblasts and is regulated by peroxisomal proliferator-activated receptorgamma/retinoid X receptor. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2003, 88, 6056–6062. [116] I. Issemann, S. Green: Activation of a member of the steroid hormone receptor superfamily by peroxisome proliferators. Nature. 1990, 347, 645–650. [117] K. Ohta, T. Endo, K. Haraguchi, J. M. Hershman, T. Onaya: Ligands for peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma inhibit growth and induce apoptosis of human papillary thyroid carcinoma cells. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2001, 86, 2170–2177. [118] B. H. Rovin, W. A. Wilmer, L. Lu, A. I. Doseff, C. Dixon, M. Kotur, T. Hilbelink: 15-Deoxy-Delta12,14–prostaglandin J2 www.ejlst.com Eur. J. Lipid Sci. Technol. 108 (2006) 70–83 regulates mesangial cell proliferation and death. Kidney Int. 2002, 61, 1293–1302. [119] J. R. G. Challis, S. J. Lye: Parturition. In: The Physiology of Reproduction. Eds. E. Knobill, J. D. Neill, Raven Press, New York (USA) 1994, pp. 985–1031. [120] M. D. Mitchell, D. L. Kraemer, D. M. Strickland: The human placenta: A major source of prostaglandin D2. Prostaglandins Leukot Med. 1982, 8, 383–387. [121] M. D. Mitchell, C. F. Grzyboski: Arachidonic acid metabolism by lipoxygenase pathways in intrauterine tissues of women at term of pregnancy. Prostaglandins Leukot Med. 1987, 28, 303–312. [122] A. K. Duttaroy, N. N. Kahn, A. K. Sinha: Interaction of receptors for prostaglandin-E1, prostacyclin and insulin in human erythrocytes and platelets. Life Sci. 1991, 49, 1129– 1139. [123] A. K. Duttaroy: Insulin-mediated processes in platelets, erythrocytes and monocytes macrophages – effects of essential fatty-acid metabolism. Prostaglandins Leukot Essent Fatty Acids. 1994, 51, 385–399. [124] J. A. Keelan, T. A. Sato, K. W. Marvin, J. Lander, R. S. Gilmour, M. D. Mitchell: 15-Deoxy-Delta(12,14)–prostaglandin J(2), a ligand for peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma, induces apoptosis in JEG3 choriocarcinoma cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1999, 262, 579– 585. [125] T. Shibata, M. Kondo, T. Osawa, N. Shibata, M. Kobayashi, K. Uchida: 15-Deoxy-delta 12,14-prostaglandin J2. A prostaglandin 14;D2 metabolite generated during inflammatory processes. J Biol Chem. 2002, 277, 10459–10466. [126] G. Ferry, V. Bruneau, P. Beauverger, M. Goussard, M. Rodriguez, V. Lamamy, S. Dromaint, E. Canet, J. P. Galizzi, J. A. Boutin: Binding of prostaglandins to human PPARgamma: Tool assessment and new natural ligands. Eur J Pharmacol. 2001, 417, 77–89. [127] K. J. Lee, H. A. Kim, P. H. Kim, H. S. Lee, K. R. Ma, J. H. Park, D. J. Kim, J. H. Hahn: Ox-LDL suppresses PMAinduced MMP-9 expression and activity through CD36mediated activation of PPARg. Exp Mol Med. 2004, 36, 534–544. [128] A. K. Duttaroy, A. K. Sinha: Purification and properties of prostaglandin-E1/prostacyclin receptor of human-blood platelets. J Biol Chem. 1987, 262, 12685–12691. [129] T. Hatae, M. Wada, C. Yokoyama, M. Shimonishi, T. Tanabe: Prostacyclin-dependent apoptosis mediated by PPAR delta. J Biol Chem. 2001, 276, 46260–46267. [130] F. R. Homaidan, I. Chakroun, H. A. Haidar, M. E. El Sabban: Protein regulators of eicosanoid synthesis: Role in inflammation. Curr Protein Pept Sci. 2002, 3, 467–484. [131] T. G. Brock, E. Maydanski, R. W. McNish, M. PetersGolden: Co-localization of leukotriene a4 hydrolase with 5lipoxygenase in nuclei of alveolar macrophages and rat basophilic leukemia cells but not neutrophils. J Biol Chem. 2001, 276, 35071–35077. © 2006 WILEY-VCH Verlag GmbH & Co. KGaA, Weinheim PPARs and their roles in human placenta 83 [132] P. R. Devchand, H. Keller, J. M. Peters, M. Vazquez, F. J. Gonzalez, W. Wahli: The PPARalpha-leukotriene B4 pathway to inflammation control. Nature. 1996, 384, 39–43. [133] P. R. Devchand, A. K. Hihi, M. Perroud, W. D. Schleuning, B. M. Spiegelman, W. Wahli: Chemical probes that differentially modulate peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor alpha and BLTR, nuclear and cell surface receptors for leukotriene B(4). J Biol Chem. 1999, 274, 23341–23348. [134] S. S. Edwin, S. L. LaMarche, D. Thai, D. W. Branch, M. D. Mitchell: 5-Hydroxyeicosatetraenoic acid biosynthesis by gestational tissues: Effects of inflammatory cytokines. Am J Obstet Gynecol.1993, 169, 1467–1471. [135] S. S. Edwin, M. D. Mitchell: Arachidonate lipoxygenase metabolite formation in gestational tissues. J Lipid Mediat Cell Signal. 1994, 9, 291–300. [136] S. S. Edwin, D. Thai, S. LaMarche, D. W. Branch, M. D. Mitchell: The regulation of arachidonate lipoxygenase metabolite formation in cells derived from intrauterine tissues. Prostaglandins Leukot Essent Fatty Acids. 1995, 52, 229–233. [137] S. S. Edwin, R. J. Romero, H. Munoz, D. W. Branch, M. D. Mitchell: 5-Hydroxyeicosatetraenoic acid and human parturition. Prostaglandins. 1996, 51, 403–412. [138] S. S. Edwin, M. D. Mitchell, D. J. Dudley: Action of immunoregulatory agents on 5-HETE production by cultured human amnion cells. J Reprod Immunol. 1997, 36, 111– 121. [139] B. A. Lopez, D. J. Hansell, T. Y. Khong, J. W. Keeling, A. C. Turnbull: Placental leukotriene B4 release in early pregnancy and in term and preterm labour. Early Hum Dev. 1990, 23, 93–99. [140] R. Romero, Y. K. Wu, M. Mazor, J. C. Hobbins, M. D. Mitchell: Amniotic fluid concentration of 5-hydroxyeicosatetraenoic acid is increased in human parturition at term. Prostaglandins Leukot Essent Fatty Acids. 1989, 35, 81–83. [141] B. M. Forman, J. Chen, R. M. Evans: Hypolipidemic drugs, polyunsaturated fatty acids, and eicosanoids are ligands for peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors alpha and delta. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997, 94, 4312–4317. [142] K. Yu, W. Bayona, C. B. Kallen, H. P. Harding, C. P. Ravera, G. McMahon, M. Brown, M. A. Lazar: Differential activation of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors by eicosanoids. J Biol Chem. 1995, 270, 23975–23983. [143] A. K. Duttaroy, A. Jørgensen: Insulin and leptin do not affect fatty acid uptake and metabolism in human placental choriocarcinoma (BeWo) cells. Prostaglandins Leukot Essent Fatty Acids. 2005, 72, 403–408. [144] L. L. Waite, R. E. Louie, R. N. Taylor: Circulating activators of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors are reduced in preeclamptic pregnancy. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2005, 90, 620–626. [Received: September 23, 2005; accepted: December 13, 2005] www.ejlst.com