Consequences of Armed Conflict in the Middle East and North

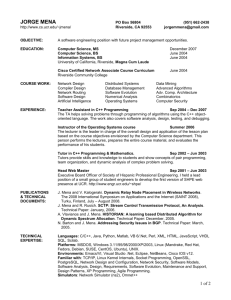

advertisement