SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT FOR DEGREE OF BACHELOR

advertisement

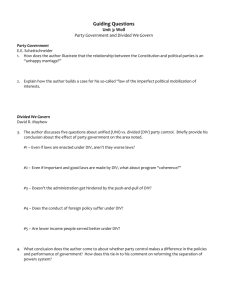

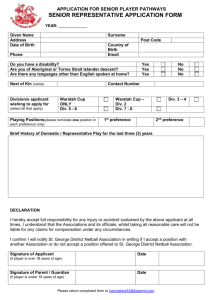

PEAK PRESSURES DUE TO STEAM BUBBLE COLLAPSE-INDUCED WATER HAMMER by GARRY WAYNE PERKINS / SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF BACHELOR OF SCIENCE at the MASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY MAY 1979 Signature of Author, ne r e*a.E De;pArment of Certified by ...---. . echanwla1 Engineering, 5-11-79 .OM '" " ' " s s 0 Thesis Supervisor Accepted by 7 D Cw h w, SChairman, D ARCHIVES MASSACHUSETTS INSTiTUTZ OF TEC HENOI.OGY JUN 26 19t9 LIBRARIES . "zm en .. 6 Committee on Thesis mental -2- PEAK PRESSURES DUE TO STEAM BUBBLE COLLAPSE-INDUCED WATER HAMMER by GARRY WAYNE PERKINS Submitted to the Department of Mechanical Engineering on May 11, 1979 in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Bachelor of Science. ABSTRACT Experiments were conducted, trying various methods of producing inertia and heat transfer controlled steam bubble collapse in a straight pipe geometry of 0.62 inches I.D. A maximum pressure value of 500 psig was observed. It was concluded that, in general, induced water hammer pressure decreases as the water temperature increases to that of saturated vapor. It was also concluded than an inertia controlled, or low water temperature collapse contributed to greater hammer pressures while heat transfer controlled decreased the water hammer effect. Peter Griffith, Professor of Mechanical Engineering -3I. Abstract - - - - - - - TABLE OF CONTENTS - - - - - - - - - Pag, - - - 2 List of Figures - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -4 Introduction - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - 5 Theoretical Analysis A. Water Hammer (General Equations) - - - - - - - - - 6 B. Inertia & Heat Transfer Controlled Water Hammer - -7 Experimental Procedure A. Experimental "Banger" - - - - - - -- - - -- - -9 B. Measuring Water Temperature & Hammer Pressure - - -9 C. Testing Modes - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - 11 Results and Discussion A. Pressure Trace Variation (one temperature) - - -12 B. C. D. E. Pressure Traces & Varying Time Sweeps - - - - - - 17 Pressures Comparing Initial Water Height - -17 Peak Pressure versus Temperature - - - - - - --20 Discussion of Errors - - - - - - --- - - - - -27 Conclusions and Recommendations - - - - - - - - - - - - 28 Acknowledgements - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -31 References - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -31 Appendix As Transducer Operating Specifications B: Thermocouple Calibration Plot - - Ct Sample Data Points for Figure H - Ds Sample Data Points for Figure G - E: Sample Data Points for Figure F - - - - - - - - - 32 33 34 37 38 -r4II. LIST OF FIGURES Page Figure 1: Generation of Water Hammer Pressure Increase - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - 6 Figure 2: Inertia and Heat Transfer Controlled Water Hammer - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - 7 Figure 3: Schematic of Experimental "Banger" - - - - - -11 Figures 4-7, Mode I, Low Temperature Scope Traces Figures 8&9: Mode I, Figure 10s Mode II, -- 13-14 Varying Time Sweep Traces - - - - -19 Varying Time Sweep Trace - - - - - -20 Figures 11-14s Mode II, Peak Pressure vs. Temperature Traces - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - 21-22 Figure Experimental "Banger" - - - - - - - - - - - - 10 Figure Plot of Mode I, Low Temperature Data - - Figure Plot of Mode I, Room Temperature Data - - - - 16 Figure Plots of Mode II, Pressure as a Function of Water Height in Reservoir - - - - - - - - -18 -15 Figure Es Plots of Mode I, Low Temperature & Room Temperature Peak Pressures - - - - - - - - - -23 Figure Mode I, Figure Mode II, Pressure vs. Temperature - - - - - - 25 Figure Mode II, Pressure vs. Temperature - - - - - - -24 Pressure vs. Temperature - - - - - - 26 -5III. INTRODUCTION During certain operating transients, such as a main feedwater pump trip, the feedwater sparger in a steam generator can lose its normal liquid cover. Cold auxiliary feedwater continues to be supplied at low flow rates to the steam generator through the sparger. A liquid/steam interface can then exist in the sparger feedpipe, creating the potential for a water hammer in the pipe if a steam bubble becomes trapped by the liquid. Steam discharges into Boiling Water Nuclear Reactor (BWR) pressure suppression pools involve similar phenomena. During the routine actuation of safety relief valves, steam is discharged into a water pool through a load-mitigation device. The violent collapse of the steam bubbles can produce water hammer type loads on the pool boundaries that can cause damage to containment walls. Similar problems would be encountered during a Loss of Coolant Accident (LOCA) in a BWR when steam discharges through the downcomer pipes.* The aim of this experimental investigation is to study the evolution of a water hammer pressure "signature" as a bubble-collapse source signal is transmitted through a piping system of known geometry and properties. Variation of a single parameter in the system will yield peak pressures as a function of the input temperature of the steam-condensing water. The results should be of use as *Taken from P. Huber's, "Proposal on Thermal Hydraulic Aspects of Reactor/Plant Eng. & Safety Analysis,"(MIT,1978,p.2). -6a baseline reference for further investigation involving the variance and measurement of multiple parameters. IV. THEORETICAL ANALYSIS A. Water Hammer(General Equatinons) Water hammer is a series A of shocks, sounding like ham1 mer blows, produced by sud- B denly reducing the flow of a fluid in a pipe. Hammer occurs when a wall of water C in a pipe must pass through a constriction such as a D partially open valve or when it is brought to a complete stop by a fully- FIG. 1-Generation of Water Hammer Pressure Increase closed valve. Figure 1 represents a vertical section of steel piping. Section A-B of the diagram contains a continuous column of moving water with an initial velocity, u initial Section C-D contains a stationary volume of water. Upon impact with the stationary water, the moving column will generate a water hammer pressure rise at C given by the following equations AP =-p c Au (1) where /o= mass density of water Au = for the water in A-B, velocity at impact less - u initial velocity(u final ) initial -7c = speed of sound in water. The value of 4860 feet/second is used when the pipe or tubing containing the water is assumed to be inelastic. When the ratio of the wall thickness to internal diameter is much less than one, the value of c must be modified to account for the elastic stretching of the wall: c* = where B = /O= E = DODi= B (2) Bulk modulus of water mass density of water Elastic modulus of steel outside diameter of pipe inside pipe diameter The time, t, for a pressure wave, produced by the water hammer effect, to travel the length of pipe L and return is given bys t = (2L)/ o (3) B. Inertia and Heat Transfer-Controlled Water Hammer •seam Dubl±e collapse ou- curs when superheated water is trapped within subcooled c water. Consider a volume of steam in a pipe between a moving column of water and a G stationary column of water. Figure 2 illustrates this phenomenon. A volume of steam is injected at F above a FIG. 2-Inertia & Heat Transfer Controlled Water Hammer -8stationary column of water at G. A moving column of water contacts the steam at E. The steam can affect the velocity of the fluid slug sufficiently to reduce the pressure increase that will occur when the water is stopped at G. Vapor bubble collapse can be classified into three categoriess (I) liquid inertia controlled, (ii) heat trans- fer controlled, and (iii) the intermediate case where both effects are of importance. If collapse is caused by a coupling of heat transfer and inertia effects, collapse rate analysis becomes complex. A dimensionless quantity can be defineds B where/ 0 j2 AT [ L k Ro , / P (4) =O density of liquid = equilibrium vapor density = reference volume of latent heat c = specific heat of liquid T = saturation temperature at final system pressure less system temperature k = thermal conductivity of liquid R = initial vapor bubble radius = final system pressure less initial equilibrium vapor pressure When B is sufficiently small, the vapor pressure becomes nearly equal to the system pressure. This is the situation where heat transfer controls the collapse. The collapse rates are relatively slow and decrease as the collapse proceeds. When B is large enough, the vapor pressure will remain close to its initial value and the collapse will be essentially controlled by liquid inertia effects. The collapse rates are high and continue to increase as the col- -9lapse proceeds. The values, B=0.30 and B=0.036, are values representing inertia dominated and heat transfer dominated collapse, respectively. The value, B=0.10, illustrates what might be termed an intermediate case where neither the heat transfer nor the liquid inertia effect is dominant; both effects play a comparable role. V. EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURE A. Experimental "Banger" Figure A is the design drawing of the "banger" used to obtain data. It is essentially a two and a half gallon steel reservoir supported by three legs in the manner of a tripod. Extending directly beneath it is a five foot length of half inch steel pipe. The floor of the reservoir (attached to the first four inches of pipe is designed to be removable and can be replaced by a drain orifice of another diameter if desired. The two longest pipe sections are joined by a specially-made cross. It allowed a pressure transducer to be placed in a 1-3/4" plug and positioned the transducer within a half inch of the pipe's stationary internal column of water. A steam inlet to the reservoir assists in controlling the bubble-collapsing water temperature. B. Meas-uringWater Temperature and Hammer Pressure A Kristal series 6606 piezoelectric pressure transducer was inserted into the banger's special cross, locating it 1-9/16" below the surface of the stationary wa- -lo- p-4__-i - srI 3 ------- .kr____~~.~_ ~..._..._ ------ 4· a~" _~k .~~__._.... ._..... ..~_~~__ -------.--- l..ri t i,. za ~ a .4, Dbd ·. ?N /SB 22V I i i i \ \ i \\ i ' /' -11ter column. Transducer specifications are included in Appendix A. A copper/constantan thermocouple was positioned near the drain at the bottom of the reservoir. An ice bath was used as a reference junction. The use of a thermocouple allowed easy temperature measurement of the reservoir water. A characteristic voltage/temperature calibration curve for the thermocouple was established and is reproduced in Appendix B. A schematic of the set-up is shown in Figure 3. E ch cJ amp _j drain FIG. 3-Schematic of Experimental Set-up C. Testing_Modes Experimental data was collected and recorded from two -12methods or modes. The following descriptions refer to Figure 3. 1. MODE Is This procedure has water contained from B to F. Low pressure steam is blown in at A. Valves B and D are then closed and C is opened. E is filled with water of a desired temperature. A and C are then closed, D is opened and a pressure trace is obtained on an oscilloscope. 2. MODE II: Tn this mode, all valves are closed except D. E is again filled with water of a desired temperature and valve A is opened for approximately four seconds, then closed. Again, a pressure trace is obtained. VI. BESULTS AND DISCUSSION A. Pressure Trace Variation for One Temperature Condition To obtain low-temperature traces, a mixture of ice and water was prepared in the banger reservoir. At first glance, the traces in Figures 4 through 7 exhibit similar characteristics. They are nearly all of the same magnitude, positive pressure rise indicated downward. All four traces are outlined by rough, erratic oscillations. This is particu- larly noticeable at the peak of Figure 5. The only significant pattern discernable is that all four traces are more sharply erratic on their initial pressure rise side. All of the traces have secondary reflections. Their outlines are less rough and jagged. -13- FIG. 4-MODE I, Low Temp. Trace Temp=2-8 0 C Scope scale: horz=2ms/div vert=0.1V/div FIG. 5-MODE I, Temp. Trace Temp=2-80C scope scale: horz=2ms/div vert=0. 1V/div Low -14- FIG. 6-MODE I, Low Temp. Trace Temp=2-80C Scope scale: horz=2ms/div vert=0. 1V/div FIG. 7-MODE I, Temp. Trace Temp=2-80 C scope scale: horz=2ms/div vert=0.1V/div Low -15FIGURE B-Mode I, Low Temperature 0C) (2-8 7¼± -T- 500 - ~1 400 - Average: 356psi -·- · -- ---·- ------- 200 - 00 - 0r Consecutive B uns 2 3! 5 . 6 7 8 91n 10 I IM 10 11 12 13 14 3? -16- 450 FIGURE C-Mode I, Room Temperature (25-30 0c) 400-- 350- Ui -- 300 oo-- ) 250 -1- i A4 ~1 200 i- 11-- 150 i Av _1 1 I 'Ki i 100 i t r 50 I i 0 2 314 5 6 i Consecutive Runsi 8 90 12 17 / 1515 3 192j2 i 22 erage i 193psi -17- Figure 6 represents the largest peak pressure obtained during any of the recorded runs for any temperature in either experimental mode. Using the following pressure/ voltage conversion factor; 1 psig = 1 millivolt the value of that pressure is , (5) 500 psi. Figures B and C illustrate the variation in peak oressure for consecutive runs for Mode I low-temperature(2-80 C) and room temperature(25-300C) data. B. Pressure Traces With VaryinS Time Sweeps Figures 8, 9, and 10 are illustrative of the detail obtainable by varying the oscilloscope time sweep speed. Figure 10 allows reasonable detail in secondary reflection traces(not detectable in Figures 4-7). However, increasing the sweep speed can overlap enough traces to become confusing. Figure 9 reduces this overlap problem, and two secondary reflections are detectable. But once again, decreasing the sweep speed can entirely wipe out detail as in Figure 8. C. PRESSURE VARIATION VS. INITIAL RESERVOIR WATER HEIGHT Figure D seems to indicate that there is a variation in peak pressure resulting from initial water height in the banger reservoir(at least at room temperature). In Mode II operation, a reservoir water height of 7*" generated a majority of pressure values above 150 psi. With an initial height of 2", the pressure generated was, generally, less -18- 5 FIGURE D-Mode II, Pressure variation as a function of water hgt in reservoir. Room Temperature. 4. i 2__ L½z~4ii 1- 0 J 51-100 0-50 - ~_III 01 151-200 1-150 201-250 Peak Pressure (psi) 4, F 714 1 o 1- C-5~L--~--1--- 0-50 ~ -- 1 51-100 I 101-150 - IL~DI S151-200 Peak Pressure (psi) .............. I I 201-250 I -19 - C FIG. 8-MODE I, Pressure Traces of Varying Time Sweeps Room Temp scope scales horz=0. lsec/div vert=O. 1V/di- FIG. 9-MODE I, Pressure Traces of Varying Time Sweeps Room Temp scope scale: horz=20ms/div vert=0.1V/div -20- FIG. 10-MODE II, Pressure Traces of Varying Time Sweeps Room Temp scope scales horz=O, lms/div vert=0.1V/div than 150 psi. D. Peak Pressure VS. Temperature Figures 11 through 14 illustrate the decreasing peak pressure with increasing temperature. This is shown graphically in Figure E as well. Two other characteristics are also noticeable: 1) Secondary reflections die out and become non-existent at higher temperatures. 2) The jagged pressure-trace outlines become more rounded and blunt. This phenomenon begins to occur around 60 0 C. In both experimental modes, it was observed that the time between the water hammer bang and initial reservoir water contact with the steam became longer and longer at higher temperatures. -21- FIG- 11-MODE II, temp=22 0 C FIG. 12-MODE II, temp=310oC Peak Pressure vs Temp Scale: horz=2ms/div vert=0.1V/div Peak Pressure vs Temp Scale: horz=2ms/div vert=0. 1V/div -22- FIG. 13-MODE II, temp=360 C Peak Pressure vs Temp horz=2ms/div Scale vert=0.1V/div FIG. 14-MODE II, Peak Pressure vs Temp Scales horz=5ms/div temp=72 C vert=O. 1V/div -23FIGURE E-Mode I Low Temperature (2-8 5 4. ri I_ K--"1 i i r 0 C) !1 2 11 0 0 1 51 1011 151 201 2517 301 3 51 K401 4511r" -50 -100 -150 -200 -250 -300 -350 -400 -450 -500 Peak Pressure (psi) re re 2 -50 -100 Peak Pressure (psi) 40Q, FIGURE F-Mode I Pressure versus Temperature. Refer to Appendix E for data. * = two points at the same location 3 50. '7* 300- 0-% XX P4 P4 150-" \ 10 O- I>, 50- ~c~i~c - -- 0t Temperature (oC) 8b -25400. FIGURE G-Mode II Pressure versus Temperature. Refer to Appendix D f'or data , * = two points at the 350- same location 2* 300-- CO q4 IoC) P4 100 -- X-- XX -. 5o0 \ I 3o0 I/ II o J I 6 Temperature (oCO • ' 10o 400 _ FIGURE H-Mode II Pressure versus Temperature. Refer to Appendix for data 350 .n 300 - 0 I IJ m )* 50 -100 3 \\ 50 J o 1\ I JI \ L 0 _ ______ " 7a 10 • - • lo Temperature (oC) Intervals of 4 0 C II 80 I1 100 -27Figures F and G are Pressure vs. Temperature plots for Modes I and II. The corresponding scatter in pressure values is indicated. Figure H is a representation of over 300 Mode II data points. To assemble them in a meaningful manner, the data has been plotted at intervals of 4 degrees Celsius. The bars indicate the two most extreme values for that particular interval. The dots are the arithmetic means of the data contained in the interval. E. Discussion of Errors 1. Thermocouple readings: The scope values could only be read to 0.05 divisions on a 2mV/div scale, thus making possible an error of + 0.lmV. This corresponds to a + 20 C conversion. Adding on the possibility of error from determining the thermocouple calibration slope and ice bath temperature variation; temperature error = + 30 C 2. Peak pressure values: Temperature transients in the pressure transducer acted to trace over the start-up points of the peak pressures. This can contribute to an uncertainty of + 0.2 div on a scale of 0.1V/div. This, in turn, implies that peak pressure values can be off by + 20 psi. 3. Mode errorst In Mode I, several errors can arise. Referring back to Figure 3, while blowing steam from A to C(with all other valves closed), the four inch section above D heated up more rapidly -28than did the water at E. The thermocouple measurements did not account for this four inch column of water. More importantly, this volume of water was what the steam first encountered when D was opened. Therefore, Mode I temperatures recorded are probably about 100C higher. Also, the line pressure of the steam inlet at A was 14 psig. Since the maximum static pressure head at D used in the reservoir was less than 14 psig, the steam pressure had to be reduced by closing C after A. The time delay in closing C varied during Mode I runs. In Mode II, better data was obtained if valve A was held open longer. VII. CONCLUSIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS In equation (4), it can be shown that as the differ- ence between the steam temperature and reservoir temperature becomes less and less, the value of B decreases. This, in turn, signifies that heat transfer-controlled steam bubble collapse is the dominating mechanism. Since collapse rates for this mechanism are relatively slow and decrease as collapse proceeds, the value of u in equation (1), or water velocity, must decrease. This gives rise to a smaller generation of water hammer peak pressures. This corollates extremely well with observations and the results plotted in Figure H. When the temperature difference between steam and reservoir water increases, B is large (signifying inertia controlled collapse). The collapse rates are high and continue to increase as collapse -29proceeds. A larger u will be generated, leading to larger water hammer pressures. This agrees with Figure H also. Evidence was found in both Mode I and II that indicate peak pressure to be a function of initial reservoir height. Comparisons of Figures F and H to Figure G show that all three graphs are similar above 600 C (with Figure F shifted to the right slightly to account for temperature errors previously discussed). Only at lower temperatures are the pressures of Figures F and H much higher than Figure G (which contains only 2 * height of water in reservoir). This does not seem peculiar when one considers that at the lower temperatures, inertia collapse dominates. More mass produces more inertia. The values obtained from both methods indicated fairly good reproducability. Aside from low start-up values in Figures B and C (probably due to trapped air bubbles), the scatter variation was reasonable. Using equation (3), one is able to determine the dura- tion of a positive pressure state. Referring to the largest pressure obtained, Figure 6, the maximum width of the large trace is approximately 1.8 divisions or 3.6 milliseconds. If the drain valve at the bottom of the vertical pipe is shut, it can be modeled as a "closed end." The reservoir can be considered an "open end." Recalling that the pressure resulting in a wave reflection from an open end is opposite in sign and reflection from a closed end retains its sign, -30one can follow the history of the pressure trace. The length of pipe below the transducer is 23 inches and the length above it is approximately 35 inches. The steam bubble-collapsing water impacts above the transducer and as the wave travels downward, there is a large rise in pressure seen at the transducer. This wave rebounds off the closed end, encounters the transducer again and increases the pressure to 500 psi. The wave hits at the open end and reflects a -500 psi pressure wave. This reduces the pressure at the transducer to zero. If the preceeding history is valid, then the wave travels a distance of 2 x (23" + 35*) or 116 inches. Plugging into equation (3) yieldes L = (3.6 ms)(1/1000) 58320in/sec = 104 inches. 2 This value is reasonably close to the correct value. Also, since the distance from the transducer to the closed end is shorter than the distance to the open end, the slope of the trace on the increasing pressure side should be steeper because of the smaller amount of time required. Figures 4 through 7 all exhibit this asymmetry. For 3.6 milliseconds, the piping system was under an induced hammer pressure. If the piping system were even longer, as in an actual nuclear piping system configuration, the piping would have to be designed to sustain high pressures during even longer periods of loading time. Also, the secondary reflected peaks ranged from j to * of the value of the initial hammer peaks. In larger systems, this can be a significant loading. -31Suggestions for future investigations are as follows: 1) Reduce the length of the four inch pipe section beneath the reservoir. Also, construct a reservoir with enough height capacity to generate a higher pressure at the quick-acting reservoir valve than the steamline pressure for Mode I runs. 2) Remove valve and unnecessary pipeline obstructions for Node II runs. 3) Collect data at the extreme temperature points (i.e. 00 C and 10000C). VIII. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I wish to express my thanks and appreciation to the following people for their time and assistance: Fred Johnson Bob Gruel Prof. P. Griffith IX. REFERENCES 1. Florschuetz, L, Chao, B., "On the Mechanics of Vapor Bubble Collapse," ASME 64-HT-35, 1964. 2. Gwinn, J., Wender, P., "Start-up Hammer in Service Water Systems," ASME 74-WA/Pwr-8, 1974. 3. Parmakian, John, Waterhammer Analysis, Dover Publications, Inc., New York, 1963. 4. Tong, L.S., Boiling Heat Transfer and Two-phase Flow, R. Krieger Publishing Co., New York, 1975. -32APPENDIX A Kristal's series 6606 low impedance quartz pressure transducer with integral electronics- - - - - - - - - - - - - - 88 8 o 0 0 6udt oo 0 0 0 U, 00 o o o oo 4 0 0 0 gO r C% < oo C 0 o Co o 0 a; o u) o 0 :- "') Cu) 0) CM E 4 E,! CO It CL a 0. VI 4oi) 0 w " rC 00 Mu ~ VIVI VO o ou d cu to 10) > p0 00oo r8CM 0 o; N 0 EEc 0 · ca 0! cnv Eo,- LLLL N z 0 C.) C1) ,> LL 0) La. I: ILi 0. U, c CC x UJ U) " -a LC) cc +i "• "0 E >, _ CC u. aC 0 ) 4- CU (D E~ +1 VU -C Cn 0,r 0 E Cu 0 , Cu C C N cN 0) 0 a)S >U ZE M . O0 - aOCu 0M LZ% U. .C EC M E EX _LL( r 0 0 ". C M0) C CM (D X 0. .c,)> >(D >' -D- t Cr, r- " :. m 00 a) 00(D 3:cE a >C ao 0 - =M -C a.00 0 : 2U a0 7F) COn cia C "0 W"Oo I Cu E ioi ,CEciE 5 "CLCT~~ " ~ c ;ý!2 = -,4) C/) 4) : ý ' > e E M C 0CC 00 ýM ZC .J C) * 0 Q.. CDe N S C.C +I C Cu,.0 0 m~ C.•4)- O~C iz) I 0) 0) C ) 0 00 0 C Q':C 0O .2 0~ I] -33- APPENDIX B 03 Cv o Y 'i\ Lo rr, cjf-> U " / C1, Fi,. C`43, f---· · -I . _ . I .. __ _____I____I . .. . .. X IL_ __ ___·I _ _~__~ __ _~____~_ 'I ;il Cj APPENDIX C Mode II Pressure vs. Temperature Datas Scope scales 2mV/div 0. Thermocouple Transducer Voltage Voltae_ - -16 0.8 o0.45 0.55 0.75 0.9 1.1 1,2 1.35 1.55 1.7 1.9 1.9 1.85 1.95 1.95 - - - V/div 1.8 2.05 0.7 2 2.1 2 1.8 1.9 1.9 1.5 1 1.3 - plotted on Fig H 2mV/div 0.1V/div Thermocouple Transducer Voltage_ Voltage 0.75 210 1.9 1.9 0.65 2 2 2 0.4 0.5 0.8 1 1.2 1.3 1.5 1.65 1.7 1*95 1.9 1.8 1.6 1.8 1.4 1.1 1.2 1.2 1 1.8 1.9 0.8 0.9 0.7 1*95 0.6 2 2.05 0.6 0.3 0.4 0.8 0.4 1.8 2 2.1 2.1 2.1 0.4 0.2 0.5 1 0.45 0.6 0.65 1.3 0.65 0.75 1.7 2.1 1.3 0*75 0.8 0.9 2 0.95 1.7 1.1 1.8 1.2 1.8 1.25 1.25 1.3 2 1.2 1.35 1.8 1.4 1.5 1.45 1.5 1.2 1.8 1.6 1.2 1.4 1.8 0.9 0.8 1.85 0.8 1.9 1.95 2 0.6 1.95 0.6 2 2.05 0.3 0.6 2.1 0.85 0.85 0.9 12 1.4 1.5 1.55 1.65 1.75 2.1 0.7 0.4 0.3 1.6 2 2.1 2.2 1.1 1.15 1.3 1.6 1.7 1.75 1.85 2.05 2.1 1.4 1.6 1.7 1.6 1.5 1.8 2 1.7 1.8 0.9 0.8 1.1 0.7 0.5 0.5 0.4 0.5 -35APPENDIX C (con't) Mode II Pressure vs. Temperature Data: Scope scale: 2mV/div Thermocouple Volta~ 0.55 0.65 0.7 0.8 0.9 1.1 1.15 1.25 1.35 1.45 1.55 1.65 1.7 1.8 1.9 2 2 2 0.4 0.5 0.65 0.75 0.85 0.95 1.1 1.2 1.25 1.4 1.5 1.55 1.65 1.7 1.8 1.9 2 0.55 0.65 0.75 0.85 0.95 0.1V/div Transducer Voltage 2.3 2 2.2 2.2 1.4 1.9 1.6 2.9 1.9 1.9 1.6 1.5 1.5 1.2 0.9 1 0.9 0.6 0.9 plotted on Fig H 2mV/div Thermocouple Voltage0.5 0.6 0.65 0.75 0.85 1.05 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 O.1V/div Transducer Voltags 2.1 2.4 2.2 1.6 1.8 1.9 2.9 1.8 1.9 1.6 1.7 1.7 0.9 1.85 1.1 1.2 1.2 0.8 1.5 1.65 1.75 1.95 2 2 0.3 0.8 1.5 0.45 2.5 2.1 2.6 2 2.2 2 2 1.8 1.9 1.4 1.7 1.5 1.2 1.1 0.7 0.7 0.6 0.7 2.5 1.6 2 0.7 3 1.9 3 1.8 0.8 0.9 1 1.15 1.25 1.3 1.45 1.5 1.6 1.7 1.75 1.85 1.95 0.5 0.6 0.8 0.9 1 2 2 2 2 2 1.9 1.9 1.6 1.2 1.4 0.9 0.9 0.9 o.6 2.7 1.4 1.9 1.8 3.2 1.6 - -36APPENDIX C (con't) Mode II plotted on Fig H Pressure vs. Temperature Data: Scope seal e: 2mV/div 0.1V/div 2mV/div 0.1V/div Thermocoup)le Voltage Transducer Voltag 2 Thermocouple Transducer 1.05 1.15 3 1.2 1.3 1.2 1.35 1.45 1.55 1.25 2 1.3 1.4 1.5 2.4 1.6 1.6 1.4 1.2 1,65 0.9 1.7 1.8 1.8 1.9 2. 2.05 2.1 0.4 0.45 0.55 1.5 1.15 1.2 1.25 1.3 1.35 1.4 1.45 0.8 0.5 0.5 0.4 2 0.5 0.6 0.65 0.7 0.8 0.85 1.8 1.6 1.1 1.9 1.4 1.4 0.6 0.4 1.3 2 1.6 2 2 1.85 0o.45 0.9 1.2 2 1 1.9 1.7 1.1 0.95 1.1 1.3 1.35 1.4 1.4 1.45 0.8 1.2 1.1 0.8 1.05 1,1 1.15 1.2 1.25 1.5 1.75 1 0.6 1.9 2 0.8 1.9 1.55 1.6 1.7 1.85 0.9 0.9 0.9 0.7 2,1 2.1 2.1 1.8 1 0.8 0.8 1.3 1.5 1.7 1.2 1.6 1.4 1.6 1.3 1 1.9 1.95 0.4 1.5 2 1,05 1.1 Voltage 0.5 1 0.8 1 1.65 1.7 - 1.75 1.6 0.95 1.55 _ 1.1 1.1 0.65 0.7 0.7 0.85 Voltage._ 1.1 0.2 1.6 1.65 1.7 1.8 1.8 2.05 0.7 1.2 2 1 1.3 1.2 1.1 1.3 1 1.2 2 0.8 0.9 1 0.9 0.8 0.6 0.6 0.2 0.3 . -37APPENDIX D Mode II Pressure vs. Temperature Datas plotted on Fig G Scope scales 2mV/div 0.1V/div 2mV/div 0.1V/div Thermocouple Transducer Thermocouple Transducer Voltaxe Voltage 1.8 1 0.8 0.35 0.55 0.8 0.85 1.4 1.5 1.6 1.7 1.75 0.7 1.8 1.65 1.75 1.75 1.8 1.9 2.05 2.15 0.9 1.4 1.25 1.45 1.55 0.8 1.1 1.1 1.3 1 0.8 1.5 1.2 1.4 0.9 1.8 1.4 1 0.6 1.5 2.2 2 0.95 0.5 0.7 Voltagge 0.8 0.9 1.1 0.7 1.05 1.2 1.3 0.8 0.8 1.8 0.7 0.2 2 2.1 0.1 1.85 2.15 0.7 0.6 0.4 0.2 0.1 _ -38APPENDIX E Temperature Datat Mode I Pressure vs. plotted on Fig F Scope scale, 2mV/div 0.1V/div 2mV/div 0.1V/div Thermocouple Transducer Thermocoup)le Transducer Voltage Voltag~ Voltag e 1 3.8 0.8 1.8 2.1 3.3 0.7 1.7 2.1 0.9 0.7 1.9 1.1 1.9 3.1 3.4 0.1 2.4 2.2 0.7 1.4 1.8 SVoltage 0.7 1.4 1.5 3.3 2.1 0.7 1.6 1.3 1.9 2.1 2.4 3.1 0.6 1.3 2.2 1.95 3.25 3.1 1.05 3.3 3.6 1 3.4 0.5 0.1 3.8 0.1 0.6 1.2 1.6 1.8 2.1 2.4 2.55 2.5 0.6 2.5 2.5 2.8 1.1 2.7 0.8 0.9 3 0.1 3.5 3 3.4 3.6 1 1.3 1.5 0.8 4.1 1.7 2 2.2 0.1 3.2 1 1.6 0.8 1.4 0.6 1.5 1.7 3.7 1.6 0.9 0.8 0.9 0.1