A new account of simple and complex reflexives in Norwegian

advertisement

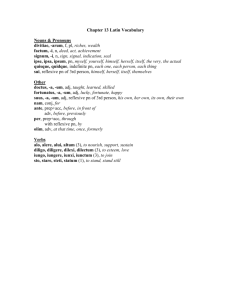

Complex reflexives 1 A new account of simple and complex reflexives in Norwegian Helge Lødrup Helge Lødrup University of Oslo Department of Linguistics and Scandinavian Studies Pb. 1102, Blindern N-0317 Oslo, Norway helge.lodrup@ilf.uio.no Phone +47 22854831 Complex reflexives 2 Abstract This article argues that the complex reflexive in Norwegian has a wider distribution than is usually assumed in the literature (for example Hellan 1988). Both simple and complex reflexives are used in the local domain, which must be defined as the minimal clause. The simple reflexive is used when the physical aspect of the referent of the binder is in focus. It is seen as an inalienable denoting the body of the referent of the binder. Its distribution follows an independently established binding principle for inalienables, while the complex reflexive is an elsewhere form. 1. Introduction Several languages show a distinction between simple and complex reflexives, and the principles for their distribution of have been the object of interesting research. This article will focus upon Norwegian, which has the simple reflexive seg and the complex reflexive seg selv1. Hellan (1988) proposed that the complex reflexive is used in local binding, while the simple reflexive is used in non-local binding (see also Hellan 1991). Local binding was understood as binding by a coargument. On this view, a typical case of the complex reflexive is (1), while a typical case of the simple reflexive is (2)2. (1) Han elsker seg selv he loves REFL SELF He loves himself Complex reflexives 3 (2) Han bad oss hjelpe seg he asked us help REFL He asked us to help him Binding by a coargument means that the antecedent and the reflexive are arguments of the same predicate (called 'strict coarguments' in Hellan 1988:69). Reflexives in PPs are different in this respect. An adjunct PP, as in (3), is outside the coargument domain of the subject. Complement PPs fall in two groups. If their preposition is semantically empty, as in (4), it is not considered a predicate, and the reflexive is a coargument of the subject. If their preposition is semantically contentful, as in (5), it is considered a predicate. The reflexive is then an argument of the preposition, and thus not a coargument of the subject. (3) Dovregubben trenger rom rundt seg Dovregubben needs space around REFL Dovregubben needs room around him (4) Han tenkte på seg selv he thought of REFL SELF He thought of himself (5) Han drar den mot he seg pulls it towards REFL He pulls it towards him Hellan's generalizations about simple and complex reflexives in Norwegian have been a basis for later work on this and other languages. For example, Complex reflexives 4 Dalrymple (1993), Reinhart and Reuland (1993) and Safir (2004) implement corresponding generalizations in different ways. I will show that these generalizations are not empirically correct; complex reflexives can be used in (what was taken to be) non-local domains, and simple reflexives can be used in (what was taken to be) local domains. Focusing upon reflexives that are objects of prepositions, I show that the simple reflexive is used when the preposition is locational, while the complex reflexive is used when the preposition is non-locational (sections 2 and 3). This generalization is independent of the grammatical status of the PP as a complement or an adjunct. I will argue that coargumenthood has no role to play in an account of simple and complex reflexives. Both are used in the local domain, but this domain is usually the minimal clause (section 4). I then argue that the generalization for simple reflexives as objects of prepositions can be extended to cover simple reflexives as objects of verbs (section 5). In both cases, the physical aspect of the referent of the binder is in focus; it is his or her physical body that is relevant. These results then serve as the basis for an account of the distribution of reflexives in which inalienables are taken as the point of departure (section 6). The simple reflexive is seen as an inalienable denoting the body of the referent of the binder, and its distribution follows an independently established binding principle for inalienables. The complex reflexive is seen as an elsewhere form. This article is based upon data from electronic corpora and the world wide web. Most example sentences are from these sources (except in section 6). Complex reflexives 5 2. Binding in adjunct PPs Section 2 shows that both simple and complex reflexives are used in adjunct PPs; the simple reflexive is used with locational PPs, while the complex reflexive is used with non-locational PPs. Adjuncts have never been in the center of research on binding. However, they are important to the understanding of the distribution of simple and complex reflexives. Norwegian is especially interesting in this respect, for two reasons: Norwegian pronouns are usually anti-subject oriented (Hestvik 1990, 1992); they cannot be bound by the subject of the minimal clause they are part of, as shown in (6). (But see notes 4 and 6.) (6) Per så en slange bak *ham / seg Per saw a snake behind him/ REFL Per saw a snake behind him Because of this anti-subject orientation, a reflexive must be used when the subject is a clause-internal binder; a pronominal is not an option (unlike English John looked around him/himself). Besides, Norwegian does not have sentences like (7) and (8) that violate basic binding theory by having antecedents that are too far away from the anaphor, as in (7), or not more prominent than the anaphor, as in (8) (see Hestvik and Philip 2001). Examples (7)-(8) are based upon sentences in Pollard and Sag (1994:270, 272) which are grammatical in English. Complex reflexives 6 (7) Johni skulle bli skuls med Mary. *Bildet av seg (selv)i i avisen ville virkelig ergre henne John should get even with Mary. picture-DEF of REFL SELF in paper-DEF would really annoy her 'John was going to get even with Mary. The picture of himself in the paper would really annoy her' (8) *Bildet av seg (selv)i i Newsweek dominerte Johnsi tanker picture-DEF of REFL SELF in Newsweek dominated John's thoughts The picture of himself in Newsweek dominated John's thoughts The lack of these 'exempt' (or 'logophoric') anaphors is important, because it means that all anaphors in Norwegian should be expected to follow the basic binding principles3. Hellan's view of simple and complex reflexives predicts that the complex reflexive should not be possible in an adjunct PP, because an adjunct PP is not a coargument of the subject of the sentence. Hellan's view implies that a reflexive in an adjunct PP must be a case of non-local binding, and it should therefore be simple. Hestvik (1990:290-91) argues that this is correct, on the basis of some sentences with locational adjuncts like (9). (9) Jon følte/hørte noe Jon felt/ nær seg *selv (Hestvik 1990:291) heard something near REFL SELF Jon felt/heard something near him Complex reflexives 7 However, these predictions are only true of the locational adjuncts. In all other types of adjuncts, the complex reflexive is used, as will be shown in the following overview of simple and complex reflexives in adjunct PPs. Prepositions can be divided into two groups (parallel to Zwarts 1997 on Dutch). One group is the traditional prepositions that have or can have a concrete locational meaning, for example i 'in', over 'over', om 'around', etc. When these prepositions are used with a locational meaning, they take the simple reflexive, as standardly pointed out in the literature. Examples are (10)-(12) (10) (de så) et stort skrog (…) over seg they saw a large hull over REFL They saw a large hull above them (11) Trond arkiverer kopi av faktura hos seg Trond files copy of invoice at REFL Trond files a copy of the invoice with him (12) Dovregubben trenger rom rundt seg Dovregubben needs space around REFL Dovregubben needs room around him A fact that is not mentioned in the literature is that the these prepositions take the complex reflexive when they are used with a non-locational meaning. Examples are (13)-(15). Complex reflexives 8 (13) Man var i et system hvor man ble bondefanget av seg selv one was in a system where one was tricked by REFL SELF One was in a system where one was tricked by oneself (14) Jernbaneverket skal konkurrere med seg selv railroad-agency-DEF shall compete with REFL SELF The railroad agency is going to compete with itself (15) (det) smertet ham mere enn han ville it pained him more than he innrømme overfor seg selv would admit to REFL SELF It pained him more than he would admit to himself One might suggest that the reason complex reflexives are used in (13)-(15) is that the adjuncts are argument-like, in the sense that they denote participants in an event. However, this idea cannot be generalized to the sentences with the next group of prepositions. The second group of prepositions is prepositions that only have an abstract meaning. Examples are angående 'concerning', av hensyn til 'out of consideration for', ifølge 'according to', på grunn av 'because of'. Some of these prepositions consist of two or three words, and the boundary between multiword prepositions and more complex structures is not clear. This question is of no real consequence in this context, however; the important point is that the reflexive will be part of an adjunct independently of analysis. These prepositions always take the complex reflexive4. Examples are (16)-(18). (16) Noen (…) ringer angående seg selv some call concerning REFL SELF Some people call concerning themselves Complex reflexives 9 (17) hun har ikke vært ute av arbeidslivet på grunn av seg she has not been out of employment-DEF because of selv REFL SELF She has not been out of employment because of herself (18) Mobberne må stanses (…) av hensyn harassers-DEF must stop-PASS til seg selv out-of concern forREFL SELF The harassers must be stopped out of concern for themselves One might suggest that the complex reflexives in sentences like (16)-(18) are bound by a local 'semantic subject' (proposed in Barbiers (2000) for Dutch). This suggestion does not work, however. The intuitive semantic subject of an adjunct is not the syntactic subject of the sentence. For example, the adjunct in (16) does not say what the syntactic subject 'some people' are about (but rather what the calling is about), and the adjunct in (17) does not say what the syntactic subject 'she' is caused by (but rather what her being out of employment is caused by)5. Examples (10)-(18) show that there is a division between adjuncts that take the simple reflexive, as in examples (10)-(12), and adjuncts that take the complex reflexive, as in examples (13)-(18). The semantic distinction between these two groups of adjuncts is clear. In (10)-(12), the adjunct has a concrete locational meaning, while in (13)-(18), it has a more abstract meaning. What kind of abstract meaning is not relevant. For the purposes of binding theory, it is sufficient to distinguish locational and non-locational meaning, with one provisio. The simple reflexive does not only require that the adjunct is locational; the location must be relative to the physical body of the referent of the binder. Complex reflexives 10 The physical body referred to does not have to be the human body. It can also be natural or artificial objects of various kinds6, as in (19). (19) Høyhus med store vindusflater kan forårsake mye ødeleggelser rundt seg high-rise-buildings with large window-faces can cause much damages around REFL High-rise buildings with large window faces can cause much damage around them It is important, however, that the location is relative to the binder's own physical body. When the location is relative to a "proxy", as in (20), the complex reflexive is used. A proxy is "in some way a representation or representative of its antecedent" (Safir 2004:112), like a figure, a picture, a novel, etc. (see Rooryck and Wyngaerd 1998, 1999, Lidz 2001). (20) Per oppdaget Kari like ved seg selv / *seg på bildet Per discovered Kari close by REFL SELF / REFL in picture-DEF Per discovered Kari close by himself in the picture If the reflexive must be interpreted as referring to the mind of the binder, as in (21), the complex reflexive is used. (21) (de søkte) løsningen på sine dilemmaer utenfor seg selv they sought solution-DEF to REFL-POSS dilemmas outside REF SELF They sought the solution to their dilemmas outside them Complex reflexives 11 It is possible to construct minimal pairs in which a simple and a complex reflexive give rise to different interpretations. An example is (22). (22) Per kunne ikke finne den hos seg / seg selv Per could not find it with REFL / REFL SELF With the simple reflexive, the adjunct refers to Per's home or office, and 'it' must refer to a concrete object, like a book. With the complex reflexive, the adjunct refers to Per's mind, and 'it' must refer to a property or a feeling. 3. Reflexives in complement PPs This section shows that reflexives in complement PPs are distributed according to the same principle as in adjunct PPs. 3.1. Hestvik's analysis and beyond Complements and adjuncts are traditionally assumed to behave differently with respect to a number of syntactic phenomena, including binding. At the same time, the complement - adjunct distinction is known to be problematic, see for example Bouma et al. (2001). The account proposed here does not depend upon this distinction, as will be seen later. Hellan's view of simple and complex reflexives predicts that a complement PP with an argument-taking preposition should take the simple reflexive as a Complex reflexives 12 case of non-local binding. This prediction is supported by sentences like (23), with the simple reflexive. (23) John kikket bak seg (Hestvik 1990:290) John looked behind REFL John looked behind him The question is what the prediction is for a complex reflexive in a complement PP. Given the view that the complex reflexive and its binder must be coarguments, the prediction is that the complex reflexive is not possible with an argument-taking preposition. A different view of the distribution of complex reflexives can be found in Hestvik (1990), (1991), who claims that both the simple and the complex reflexive can occur in a complement PP with an argument-taking preposition. Hestvik assumes that there are binding domains without subjects (building upon work by Joan Bresnan). In his theory, a PP can be a subjectless binding domain. The simple reflexive in a sentence like (23) is then a non-local reflexive that is free in the PP domain. Hestvik proposes that a complex reflexive does not have to be a coargument of its binder. His alternative is that a complex reflexive and its binder must be in a minimal domain that contains a subject7. For a complex reflexive in a complement PP, this domain is the minimal clause that contains the PP. Hestvik gives examples like (24)-(25) to support his claim that both the simple and the complex reflexive are possible in complement PPs. Complex reflexives 13 (24) John kikket bak seg / seg selv (Hestvik 1990:290) John looked behind REFL / REFL SELF John looked behind him (25) John skjøv Marit fra seg / seg selv (Hestvik 1990:290) John pushed Marit from REFL / REFL SELF John pushed Marit from him Hestvik finds both the simple and the complex reflexive acceptable in (24)(25), but he notes that there are speakers who don't accept the complex reflexive. For one of his example sentences, (26) below, Hestvik (1991:470) observes that the choice between the simple and the complex reflexive gives a difference in meaning. (26) John satte Marit foran seg / seg selv (Hestvik 1991:470) John put Marit in front of REFL / REFL SELF John put Marit in front of him With the simple reflexive, (26) means that John positions Marit physically, relative to his body. With the complex reflexive, it means that John evaluates Marit relative to his own person (for example as an artist, a surgeon, etc.). This is the same kind of difference between locational and non-locational meaning that was found with adjuncts. The basic generalization for complement PPs turns out to be the same as for adjunct PPs. Complement PPs with locational (including directional) prepositions have the simple reflexive, as in (27)-(29). Complex reflexives 14 (27) de er i ferd med å skylle av seg vaskevannet they are in process of to rinse off REFL wash-water-DEF They are rinsing off the wash water (28) Hun tok hånden hans og la den mot seg She took hand-DEF his and put it towards REFL She took his hand and put it towards her (29) (hun) tar et handkle om she puts a towel seg around REFL She puts a towel around her Sentences with non-locational complements have the complex reflexive, as in (30)-(32). (30) Brink burde kreve Brink should demand mer av seg selv more of REFL SELF Brink should demand more of himself (31) Noen folk må reddes fra seg selv some people must save-PASS from REFL SELF Some people must be saved from themselves (32) Han tenkte på seg selv he thought of REFL SELF He thought of himself Complex reflexives 15 3.2 Metaphorical use It is not clear if the prepositions in sentences like (30)-(32) constitute predicates, or if they should be considered semantically empty. If they do not constitute predicates, their object is a coargument of the subject of the clause, and Hellan's view correctly predicts the complex reflexive in (30)-(32). However, at least for some complement PPs with non-locational meanings, it could be argued that their prepositions are not semantically empty, but rather used metaphorically. They would then constitute predicates, and Hellan's theory would predict that they take the simple reflexive. In the account of reflexives presented here, complement PPs are predicted to take the complex reflexive when they are not locational, independently of the predicate status of their preposition. Some prepositions show a rather clear-cut division between a locational and a metaphorical use. The distribution of reflexives is as expected; the metaphorical use takes the complex reflexive, and the locational use takes the simple reflexive. One example is the preposition mot, whose meaning is either the directional 'towards' or the metaphorical 'against' (Kristoffersen 2001), as in (33)-(34). In a similar way, the meaning of the preposition om is either the locational 'around' or the metaphorical 'concerning', as in (35)-(36). (33) (han) drar den mot seg he pulls it towards REFL He pulls it towards him Complex reflexives 16 (34) Forbrukerrådet argumenterer mot consumer-council-DEF argues seg selv against REFL SELF The consumer council argues against itself (35) de spredte en karakteristisk odør om seg they spread a characteristic smell around REFL They spread a characteristic smell around them (36) De vil fortelle om seg selv they will tell about REFL SELF They will tell about themselves In other cases, as in (26) above, it is not the preposition in itself that is used metaphorically, but rather the verb and the preposition together. 3.3 Fixed expressions There is a number of more or less idiomatic fixed expressions in which the simple reflexive is the object of a preposition, for example (37)-(40). (37) koste på seg noe treat on REFL something treat oneself to something (38) ha press på seg have pressure on REFL be under pressure Complex reflexives 17 (39) legge noe put under seg something under REFL conquer something (40) ta mot til seg take courage to REFL pluck up courage This kind of idioms take the simple reflexive (see Everaert 1986:47-49 on Dutch). This fact might be unexpected, because their meaning is not locational. On the other hand, the reflexive cannot be replaced by an ordinary noun phrase (without losing the idiomatic meaning). They could therefore be seen as non-thematic. Non-thematic reflexives are always simple, see note 28. 4. Binding domains This section discusses binding domains for reflexives, arguing that both simple and complex reflexive are used in local binding, and that the local domain should be defined as the minimal clause The basic generalization is the same with adjunct and complement PPs: The simple reflexive is used in a PP that denotes location relative to the physical body of the referent of the binder. The complex reflexive is used elsewhere. This account is very different from Hellan's view that the simple reflexive is used in non-local binding, while the complex reflexive is used in local binding. Hellan's view predicts a syntactically conditioned complementary Complex reflexives 18 distribution that is not empirically correct (see especially (10)-(12) versus (13)(15), and (22)). The account proposed here has consequences for the understanding of binding domains. Hellan takes local binding to be binding by a coargument, predicting that the complex reflexive can only be bound by a coargument. It was shown, however, that both adjunct and complement PPs take the complex reflexive when the meaning is not locational. To single out the obvious cases of non-local binding that require the simple reflexive9, it is necessary to redefine the concept of local domain for Norwegian reflexives. Their local domain must be larger than is usually assumed. It is necessary to go back to a simpler definition of binding domains. In the first generative work on reflexives, locality was defined in terms of the binder and the reflexive being in the "same simplex sentence" (Lees and Klima 1963), or being "clause mates" (Postal 1971:13). The local domain that is needed here is the clause, understood as a predication with a subject and a predicate, and complements and adjuncts, if any. This concept also covers secondary predications, as in (41)-(43). (41) Vi ba [hami kikke bak we asked him look segi] behind REFL We asked him to look behind him (42) Vi gjorde [hami stolt we made him proud av seg selvi] of REFL SELF We made him proud of himself Complex reflexives 19 (43) Vi gjorde [hami til talsmann for seg we made him selvi] into spokesman for REFL SELF We made him a spokesman for himself This clausal domain is the domain in which both the simple and the complex reflexive are used, depending upon meaning. The clausal domain is also the domain for the anti-subject-orientation of pronouns (which requires a special domain in Hellan's theory). Outside this local domain, the simple reflexive is used. An independent argument for this view is given by the proxy reflexives. They must always be complex. The only exception involves non-local binding (Safir 2004:132), as in (44), in which the proxy is in an embedded non-finite clause. (44) Karii bad meg kikke ved siden av segi på bildet Kari asked me look beside REFL in picture-DEF Kari asked me to look beside her in the picture This generalization - and exception - require locality to be defined as above. Proxy reflexives cannot be simple in the other contexts that are non-local when locality means coargumenthood. For example, proxy reflexives must always be complex in adjunct PPs, see (20) above. Binding domains cannot be discussed without mentioning reflexives in noun phrases. They introduce problems for the understanding of binding domains, which can only be discussed briefly here. Complex reflexives 20 Hellan assumed (as is usual in the literature) that noun phrases define separate binding domains when the head noun has argument structure. Consider (45), from Hellan 1988:69, with his question marks. (45) ??Jon leste [noen omtaler av seg selv] Jon read some reviews of REFL SELF Jon read some reviews of himself On Hellan's view, (45) is a case of non-local binding. The reflexive is within the noun phrase, and the binder is the clausal subject. The binder and the reflexive are not coarguments, and the prediction is that the reflexive should be simple. However, web searches show that the complex reflexive is most often used with omtale 'review' and comparable nominalizations. Sentences with the simple reflexive are unusual in texts, even if they are usually acceptable to me and other speakers. This seems to be the basic tendency with other nominalizations as well. Examples are (46)-(47). (46) (Han) opplevde virkelig [overgrep mot seg selv] he experienced really harassments against REFL SELF He really experienced harassments against himself (47) ingen bør påtvinges [følsom informasjon om seg selv] nobody should force-upon-PASS sensitive information about REFL SELF Nobody should be forced to receive sensitive information about themselves Complex reflexives 21 Even in noun phrases with possessives, the complex reflexive is often found when the binder is outside the noun phrase, as in (48). (48) huni vil påkalle [politiets interesse for seg selvi] she will evoke the police's interest for REFL SELF She wants to evoke the police's interest for her This is an important indication that noun phrases are not necessarily separate binding domains (see Keller and Asudeh 2001, Asudeh and Keller 2001 on English picture nouns). 5. Reflexive objects of verbs This section argues that the generalization for simple and complex reflexives in PPs is an instance of a more general principle for the distribution of simple and complex reflexives. Hellan (1988) pointed out that the verbs that take a complex reflexive object (like elske 'love') "express a relation with a mental object as the second part, or what we might call a ´full personality´, rather than just a physical aspect of a person" Hellan (1988:113). The verbs that take the simple reflexive, on the other hand, denote actions that are directed towards 'a physical aspect of a person'. Typical examples are verbs denoting grooming actions, but there are also verbs that denote other actions directed towards the body, for example piske 'flog'. Differing from Hellan (1988:104-30), Hestvik (1990:94-120) and others, it is assumed here that these verbs can have an analysis as ordinary Complex reflexives 22 transitive verbs with the simple reflexive as a thematic object. Some arguments can be found in Everaert (1986:96-98), Lødrup (1999), Kiparsky (2002:212), Bergeton (2004: 231-263)10. There is one generalization that covers these verbs and the locational prepositions: the physical aspect of the referent of the binder is in focus; it is his or her physical body that is relevant. This is called a physical context in Lødrup (1999), see also Bresnan (2001:254-61). Physical contexts can be defined as those in which the action is on or in relation to a person's physical body, or something is located relative to a person's physical body (modified from Bresnan 2001:258). Note that a reflexive in a physical context is fundamentally different from a proxy. A reflexive in a physical context refers to the physical body of the referent of the antecedent. A proxy, on the other hand, refers to an object that is distinct from (but related to) the referent of the antecedent. A person is conceptualized as having two 'parts', the body and the mind (or the 'self' and the 'subject' of Lakoff (1996)). The simple reflexive stands for the body of the binder. However, it is not clear that the complex reflexive stands for his or her mind (as hinted in the Hellan quotation above). For example, Norwegian forakte 'despise' and snakke om 'talk about' both take the complex reflexive, but neither excludes one's body from being a part of what is despised or talked about. It would probably be better to see the complex reflexive as an elsewhere form that is used outside the physical contexts. The distribution of the simple and complex reflexive can then be described in the following way: In a local domain (in the sense of section 4), the simple reflexive is used in a physical context, while the complex reflexive is used elsewhere. Complex reflexives 23 6. Inalienables The question is now why the simple reflexive should stand for the body of the binder, or, more generally, why the concept of the physical body is relevant to the distribution of reflexives. The answer is to be found in the relation between reflexives and inalienables. I will argue that the simple reflexive is an inalienable, whose distribution follows an independently established binding principle for inalienables. A traditional idea is that there is some kind of similarity between inalienables and the complex reflexive, or the self element (Faltz 1985:31-34, Guéron 1985, Pica 1987, Safir 1996, Pica and Snyder 1997, Postma 1997, Rooryck and Vanden Wyngaerd 1998, 1999, Safir 2004:195-98). Lødrup (1999) makes use of the relation between reflexives and inalienables in a different way. This approach was based upon the grammatical similarity between inalienables and simple reflexives (an observation attributed to L[ars] Johnsen in Vergnaud and Zubizarreta (1992:622, note 37)). Inalienables usually require a possessor to be syntactically realized. The possessor can be realized internally or externally to the phrase that contains the inalienable. It is internal in (49), in which it is realized as a possessive, and external in (50), in which it is realized as the subject of the sentence. (49) Han elsker hendene he loves sine hands-DEF REFL-POSS He loves his hands Complex reflexives 24 (50) Han vasker hendene he washes hands-DEF He washed his hands The external possessor is always the subject in Norwegian, except in sentences with possessor raising (Hun vasket ham på hendene 'She washed him on the hands')11. An important fact about inalienables is that they do not occur freely with external possessors. For example, (49) above would have been ungrammatical without the internal possessor. Lødrup (1999) shows that definite inalienables with external possessors can be used in the same contexts as the simple reflexive, namely the physical contexts12. Examples are (51)-(53). (51) Han vasket seg he / hendene washed REFL / hands-DEF He washed himself / his hands (52) Hun tar et handkle om she puts a towel seg / hodet around REFL / head-DEF She puts a towel around her / her head (53) Han kjente sagmugg under seg / he felt føttene sawdust under REFL / feet-DEF He felt sawdust under him / his feet Contexts that require the complex reflexive require inalienables with internal possessors, as in (54)-(56). (To avoid the interpretation where the inalienables Complex reflexives 25 are used as ordinary definite nouns, one could think of the example sentences as the first sentence of a discourse.) (54) Kongen elsker seg *(selv) / hendene king-DEF loves *(sine) REFL SELF / hands-DEF REFL-POSS The king loves himself / his hands (55) Kongen tenkte på seg *(selv) / hendene *(sine) king-DEF thought of REFL SELF / hands-DEF REFL-POSS The king thought of himself / his hands (56) Kongen betrodde seg til meg angående seg *(selv) / hendene ?? (sine) king-DEF confided REFL to me concerning REFL SELF / hands-DEF REFLPOSS The king confided in me concerning himself / his hands The proxy reading requires complex reflexives, and it also requires inalienables with internal possessors. Examples (57)-(58) can only have the 'wax museum interpretation' (Jackendoff 1992) when the inalienables have internal possessors. (57) Ringo vasket hendene (sine) Ringo washed hands-DEF REFL-POSS Ringo washed his hands (58) Ringo tar et håndkle om Ringo puts a towel hodet (sitt) around head-DEF REFL-POSS Ringo puts a towel around his head Complex reflexives 26 We see, then, that the distribution of inalienables with external possessors parallels the distribution of simple reflexives. Inalienables with external possessors are used in physical contexts, while inalienables with internal possessors are used elsewhere. Binding theory must have a principle saying that an inalienable is bound by its possessor in a physical context (Lødrup 1999, Bresnan 2001:254-61). This principle will also account for the simple reflexive in its local use, where it should be seen as an inalienable that denotes the body as a whole. This gives a principled basis for its distribution. The domain in which inalienables are bound by their external possessors is the clause. There are no non-local inalienables with external possessors, as shown in (59). (59) Hani ba meg vaske hendene ??(sinei) he asked me wash hands-DEF REFL-POSS He asked me to wash his hands This means that the local binding domain for inalienables is the one that was proposed for reflexives, namely the minimal clause. This follows from the definition of physical contexts, and gives an argument for the approach to binding domains taken here. Complex reflexives 27 7. Problems and alternatives 7.1 The intensifier selv 'self' The main problem for the present proposal - and probably for any account of simple and complex reflexives in a language like Norwegian - is the existence of selv 'self' as a focusing or intensifying particle (Hellan 1988:63-4, Bergeton 2004). The intensifier selv 'self' is used independently of reflexives. All occurrences of the simple reflexive, except non-thematic and non-local uses, can have intensifying selv 'self', with varying degrees of naturalness. Examples are (60)-(61). (60) Han pisket seg (selv) he flogged REFL SELF He flogged himself (61) Han så en slange bak seg (selv) he saw a snake behind REFL SELF He saw a snake behind him The complex reflexive looks like the simple reflexive followed by the intensifier. It is possible to distinguish between them, however (see Hellan 1988:63-64). The intensifier selv 'self' introduces a "contrastive, contrary-toexpectation element" (Levinson 1991:131). This element is a part of the interpretation of both (60) and (61) - more naturally in (60), in which the meaning of verb makes agent-patient coreference unexpected (see Faltz 1985:239-43). Complex reflexives 28 The complex reflexive is also different from the simple reflexive followed by the intensifier in that the complex reflexive does not necessarily introduce the "contrastive, contrary-to-expectation element". For example, verbs that require the complex reflexive as an object (like elske 'love'), cannot give up this requirement, even if the context makes coreference expected13. Even if the complex reflexive can be distinguished from the simple reflexive followed by the intensifier, care must be taken when simple and complex reflexives are investigated. The question to ask is not where seg selv is possible (because it very often is), but rather where seg is possible, and where seg selv is obligatory. 7.2 Semantic approaches There are other approaches to the distribution of simple and complex reflexives in local domains that have in common with the present approach that they are based on meaning. Even if Norwegian has not been in the focus, they deserve a short mention here. Haiman (1983) proposed that the simple reflexive is used when the verb denotes actions that one usually performs upon oneself, while the complex reflexive is used when the verb denotes actions that one usually performs upon others. This approach is discussed by Smith (2004), who points out its weaknesses, for example its inability to account for the fact that the Norwegian verb piske 'flog' takes the simple reflexive (which is predicted by the present approach). Haiman (1983) also proposed an additional factor, the degree to which the participants in the event denoted by the sentence are Complex reflexives 29 distinguishable; Smith (2004) shows that this principle is empirically inadequate, and that it is problematic on conceptual grounds. 9. Conclusion It has been shown that the local domain for binding must be the clause, rather than a predicate and its arguments, and that this is the local domain for both simple and complex reflexives in Norwegian. The distribution of the simple and complex reflexives in this domain is semantically based. The simple reflexive is an inalienable denoting the physical body of the referent of the binder, while the complex reflexive is an elsewhere form. This gives a very different picture of the distribution of simple and complex reflexives, and of binding domains, than is usually seen in the literature. Danish, Swedish and Dutch have simple and complex reflexives whose distribution is known to be rather similar to Norwegian. No explicit comparison exists, however, and it remains to be seen if the account presented here carries over to these languages. Complex reflexives 30 Notes 1 Forms like ham selv 'him self' (consisting of a non-reflexive pronoun and selv 'self') are assumed to be anaphors in Hellan (1988). I assume that selv with a non-reflexive pronoun is an intensifying particle, which is not subject to binding theory (see Bergeton 2004:212-220). 2 Non-thematic reflexives, as in (i)-(ii), are always simple (Hellan 1988:120); they will be put aside in this article. (i) Han innfant seg på kontoret he appeared REFL at office-DEF He appeared at the office (ii) Han løp seg he svett ran REFL sweaty He ran himself sweaty 3 Norwegian has reflexives without visible binders, as in (i). (i) Judo utvikler (…) respekt for seg selv og andre judo develops respect for REFL SELF and others Judo develops respect for oneself and others These reflexives always have a generic interpretation, and they are not directly relevant to the discussion here (see Lødrup 2007). 4 In non-local binding (as defined in section 4), the simple reflexive must be used. With some of the prepositions in this group, forms like ham selv 'him self' (consisting of a non-reflexive pronoun and selv 'self') would be a more or less acceptable alternative to the reflexive, violating the general anti-subjectorientation of Norwegian pronouns. 5 Rooryck and Vanden Wyngaerd (1998) mention that the second group of prepositions in Dutch take complex reflexives. They connect this property to Complex reflexives 31 the fact that these prepositions do not allow preposition stranding, assuming that the simple reflexive has to move covertly. Apart from the problems with a movement analysis of reflexives (Safir 2004:164-66), this analysis gets less attractive when one considers the fact that the previous group of prepositions always allow preposition stranding; this is also the case when they are used with a non-locational meaning and take the complex reflexive. 6 It is interesting, however, that an inanimate subject can in some cases bind a pronoun, violating the general anti-subject orientation of pronouns in Norwegian (Lødrup 2006). An example is (i). (i) Enkelte LCD-skjermer har et elektroluminiserende panel bak dem some LCD-screens have an electro-illuminating panel behind them 'Some LCD screens have an electro-illuminating panel behind them' 7 Hestvik makes use of the well-known asymmetry between principle A and principle B (Huang 1983): principle A requires a domain with a subject, while principle B doesn't. 8 A case in which the simple reflexive is unexpected concerns the PP for seg 'for REFL' with verbs like betale 'pay' or svare 'answer'. This case differs from (37)-(40) in that the reflexive can be replaced by an ordinary noun phrase. Even so, the phrases in question might have been lexicalized as fixed expressions. It is striking that the PP does not really add to the meaning; the expression betale for seg 'pay for REFL' usually means the same without the PP. (This is also true of adjunct PPs like uten kostnader for seg 'without expenses for REFL'.) 9 I disregard sentences like (i), which can be reasonably acceptable with a complex reflexive in non-local binding. (i) hun trodde hun gjorde det som var best for seg selv Complex reflexives 32 she thought she did that which was best for REFL SELF She thought she did what was best for herself Sentences like (i) are only acceptable when the subject of the subordinate clause is inanimate. It is well known from many languages that inanimate subjects do not always count as binders (Lødrup 2006). 10 In some cases, it is difficult to distinguish between simple reflexive objects and lexical reflexives (see Lødrup 1999, especially notes 3 and 4). It could also be mentioned that indirect object reflexives are most often complex, as in (i). (i) De ga seg selv poeng they gave REFL SELF points They gave themselves points This is expected, because a benefactive is usually a human or an institution, whose abstract sphere of interests is affected by the action. However, a verb like iføre 'put on' takes an indirect object that is not benefactive. It is locational, and the simple reflexive is used, as in (ii). (ii) Politikeren iførte seg gorilladrakt politician-DEF put-on REFL gorilla-suit The politician put on a gorilla suit 11 Norwegian does not have the external dative possessors that can be found in several European languages, for example German and French. An example is the French sentence (i), from Vergnaud and Zubizarreta (1992:597). Note that the inalienable is the direct object in this construction, while the possessor is the direct object in possessor raising. (i) Le médecin leur the doctor a examiné la gorge to-them examined the throat The doctor examined their throats Complex reflexives 33 12 Inalienables with external possessors also share other properties with simple reflexives. For example, they only allow the sloppy reading in comparative deletion sentences like (i) and (ii) (see Sells, Zaenen and Zec 1987). (i) Bestefar vasket seg bedre enn Lillebror Grandfather washed REFL better than Little-brother Grandfather washed himself better than Little brother (ii) Bestefar vasket hendene bedre enn Lillebror Grandfather washed hands-DEF better than Little-brother Grandfather washed his hands better than Little brother 13 Bergeton (2004) proposes that the complex reflexive should always be seen as seg followed by the intensifiser. This view seems to be hard to reconcile with the fact that the complex reflexive is obligatory in many contexts. Complex reflexives 34 Acknowledgements This work has benefitted from discussions with audiences at Oslo and Stanford, and the LSA Annual Meeting 2006 in Albuquerque, NM. I would especially like to thank Jenny Graver, Trine Egebakken, Janne Bondi Johannessen, Joan Bresnan, Peter Sells and Paul Kiparsky. Thanks also to the three anonymous reviewers for detailed and useful comments. Complex reflexives 35 References Asudeh, Ash and Frank Keller: 2001, 'Experimental Evidence for a Predication-based Binding Theory', in M. Andronis, C. Ball, H. Elston, and S. Neuvel (eds.), CLS 37: The main session, Chicago Linguistic Society, Chicago, pp. 1-14. Barbiers, Sjef: 2000, 'On the Interpretation of Movement and Agreement: PPs and Binding', in H. Bennis, M. Everaert and E. Reuland (eds.) Interface strategies: Proceedings of the colloquium, Amsterdam, 24-26 September 1999, Koninklijke Nederlandse Akademie van Wetenschappen, Amsterdam, pp 2136. Bergeton, Uffe: 2004, The Independence of Binding and Intensification, unpublished Ph.D. dissertation, USC. Bouma, Gosse, Rob Malouf, and Ivan A. Sag: 2001, 'Satisfying Constraints on Extraction and Adjunction', Natural Language and Linguistic Theory 19, 1, 1-65. Bresnan, Joan: 2001, Lexical-Functional Syntax. Blackwell, Oxford. Dalrymple, Mary: 1993, The Syntax of Anaphoric Binding. CSLI, Stanford. Everaert, Martin: 1986, The Syntax of Reflexivization. Foris, Dordrecht. Faltz, Leonard M.: 1985, Reflexivization: A Study in Universal Syntax. Garland, New York. Guéron, Jacqueline: 1985, 'Inalienable Possession, PRO-inclusion and Lexical Chains', in J. Guéron, H.-G. Obenauer and J.-Y. Pollock (eds.) Grammatical Representation, Foris, Dordrecht, pp. 43-86. Haiman, John: 1983, 'Iconic and Economic Motivation', Language 59, 4 781-819. Hellan, Lars: 1988, Anaphora in Norwegian and the Theory of Grammar, Foris, Dordrecht. Complex reflexives 36 Hellan, Lars: 1991, 'Containment and Connectedness Anaphors', in J. Koster and E. Reuland (eds.) Long-Distance Anaphora, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 27-48. Hestvik, Arild: 1990, LF Movement of Pronouns and the Computation of Binding Domains, unpublished Ph.D. dissertation, Brandeis University. Hestvik, Arild: 1991, 'Subjectless Binding Domains', Natural Language and Linguistic Theory 9, 3, 455-496. Hestvik, Arild: 1992, 'LF Movement of Pronouns and Antisubject Orientation', Linguistic Inquiry 23, 557-594. Hestvik, Arild and William Philip: 2001, 'Syntactic vs. Logophoric Binding: Evidence from Norwegian Child Language', in P. Cole, G. Hermon and J. Huang (eds). Syntax and Semantics: Long Distance Reflexives, vol. 33, Academic Press, New York, pp. 119-39. Huang, C.-T. James: 1983, 'A Note on the Binding Theory', Linguistic Inquiry 14, 3 554-60. Jackendoff, Ray: 1992, 'Madame Tussaud meets the binding theory', Natural Language and Linguistic Theory, 10, 1 1-31. Keller, Frank and Ash Asudeh: 2001, 'Constraints on Linguistic Coreference: Structural vs. Pragmatic Factors', in Proceedings of the 23rd. Annual Conference of the Cognitive Science Society, Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Mahwah, NJ, pp. 483-488. Kiparsky, Paul: 2002, 'Disjoint Reference and the Typology of Pronouns', in I. Kaufmann and B. Stiebels (eds.), More than Words, Studia Grammatica 53, Akademie Verlag, Berlin, pp. 179-226. Kristoffersen, Kristian: 2001, 'Semantic Structure of the Norwegian Preposition mot', Nordic Journal of Linguistics 24, 1, 3-28. Complex reflexives 37 Lakoff, George: 1996, '"Sorry, I’m Not Myself Today": The Metaphor System for Conceptualizing the Self', in G. Fauconnier and E. Sweetser (eds.) Spaces, Worlds, and Grammars, University of Chicago Press, Chicago, pp. 91-123. Lees, Robert B. and Edward S. Klima: 1963, 'Rules for English Pronominalization', Language 39, 1, 17-28. Levinson, Stephen C.: 1991, 'Pragmatic Reduction of the Binding Conditions Revisited', Journal of Linguistics 27, 107-161. Lidz, Jeffrey: 2001, 'Anti-antilocality', in P. Cole, G. Hermon and J. Huang (eds). Syntax and Semantics: Long Distance Reflexives, vol. 33, Academic Press, New York, pp. 227-254. Lødrup, Helge: 1999, 'Inalienables in Norwegian and Binding Theory', Linguistics 37, 3, 365 - 388. Lødrup, Helge: 2006, Animacy and Long Distance Binding: The Case of Norwegian' http://folk.uio.no/helgelo/index.html Lødrup, Helge: 2007, 'Norwegian Anaphors without Visible Binders'. Journal of Germanic Linguistics 19, 1 1-22. Pica, Pierre: 1987, 'On the Nature of the Reflexivization Cycle', in J. McDonough and B. Plunkett (eds.) Proceedings of the North East Linguistic Society 17. GLSA, Department of Linguistics, University of Massachusetts, pp. 483-499. Pica, Pierre and William Snyder: 1997, 'On the Syntax and Semantics of Local Anaphors in French and English', in A.-M. Di Sciullo (ed.) Projections and Interface Conditions: Essays on Modularity, Oxford University Press, New York, pp. 235-250. Pollard, Carl and Ivan A. Sag: 1994, Head-driven Phrase Structure Grammar. University of Chicago Press, Chicago. Complex reflexives 38 Postal, Paul M.: 1971, Cross-over Phenomena. Holt, Rinehart and Winston, New York. Postma, Gertjan: 1997, 'Logical Entailment and the Possessive Nature of Reflexive Pronouns', in H. Bennis, P. Pica and J. Rooryck (eds.) Atomism and Binding, Dordrecht, Foris, pp. 295-322. Reinhart, Tanya, and Eric Reuland: 1993, 'Reflexivity', Linguistic Inquiry 24, 4, 657-720. Rooryck, Johan and Guido Vanden Wyngaerd: 1998, 'The Self as Other: A Minimalist Account of zich and zichzelf in Dutch', in P. Tamanji and K. Kusumoto (eds.) Proceedings of the North East Linguistic Society 28, GLSA, University of Massachusetts, Amherst, pp. 359-373. Rooryck, Johan and Guido Vanden Wyngaerd: 1999, 'Puzzles of Identity: Binding at the Interface', in P. Tamanji, M. Hirotani and N. Hall (eds), Proceedings of the North East Linguistic Society 29, GLSA, University of Massachusetts, Amherst, Safir, Ken: 1996, 'Semantic Atoms of Anaphora', Natural Language and Linguistic Theory 15, 545-589. Safir, Ken: 2004, The Syntax of Anaphora. Oxford University Press, Oxford. Sells, Peter, Annie Zaenen and Draga Zec: 1987, 'Reflexivization Variation: Relations between Syntax, Semantics, and Lexical Structure', in M. Iida, S. Wechsler and D. Zec (eds.) Working Papers in Grammatical Theory and Discourse Structure, CSLI Publications, Stanford, CA, pp. 169-238. Smith, Mark: 2004, 'Light and heavy reflexives', Linguistics 42, 3 573-615. Vergnaud, Jean-Roger and Maria Luisa Zubizarreta: 1992, 'The Definite Determiner and the Inalienable Construction in French and English', Linguistic Inquiry 23, 595-652. Complex reflexives 39 Zwarts, Joost: 1997, 'Complex Prepositions and P-stranding in Dutch', Linguistics 35, 6 1091-1112.