MIT Sloan School of Management January 2002 Labor-Management Cooperation on Teaching

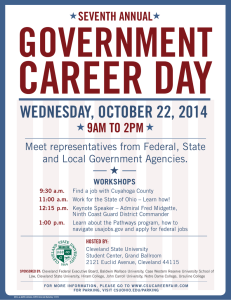

advertisement