Running an Effective Induction Program for New Sales Recruits:

advertisement

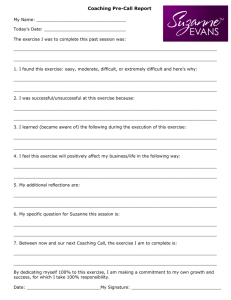

Journal of Selling Running an Effective Induction Program for New Sales Recruits: Lessons from the Financial Services Industry By Zahed Subhan, Roger Brooksbank, Scott Rader, Duncan Steel, and Kimberley Mackey Little research to date has considered how best to deploy the training and coaching activities that typically combine to form the basis of a salesperson induction program. Accordingly, set within the context of the embattled financial services industry, this paper seeks to profile the key characteristics of a successful induction program for new sales recruits. Based on depth interviews with senior business development executives from two “matched pairs” of higher and lower performing financial services companies in the United Kingdom and New Zealand respectively, the study identifies a number of practical “how-to-do-its” for planning and executing a successful induction program. In particular, the findings indicate that above all else, the higher performers are differentiated from their lower performing counterparts by the extent to which they have sought to properly integrate and align their sales training and sales coaching activities. Key Words: Sales training, salesperson induction, coaching, financial services selling, depth interviews Introduction The bar has been raised. In a world where businesses are becoming increasingly proficient at managing a wide range of multi-channel, multi-touch customer interactions, how can we help new salespeople to measure up to customers’ expectations? Across many industries, professional salespeople perform a dizzying number of essential tasks such as prospecting for new customers, selling goods and services that are well matched to each customer’s requirements and, through providing customer service and undertaking other customer care and relationship building activities, facilitating longer term “repeat selling,” “up selling,” and “cross selling” opportunities (Ennew and Waite 2012; Kaishev, Nielsen Zahed Subhan (Ph.D., University of Leeds, UK), Assistant Professor of Entrepreneurship, Sales and Marketing, Western Carolina University, zsubhan@wcu.edu. Roger Brooksbank (Ph.D., University of Bradford, UK), Associate Professor of Marketing, Waikato Management School, University of Waikato, rogerb@waikato.ac.nz. Scott Rader (Ph.D., University of Tennessee, USA), Assistant Professor of Entrepreneurship, Sales and Marketing, Western Carolina University, srader@wcu.edu. Duncan Steel (Master of Sales Management, University of Portsmouth, UK), Managing Director, Sales Training IQ, duncanwsteel@gmail.com. Kimberley Mackey (Bachelor of Management Science, University of Waikato, New Zealand), Marketing Communications and Events Coordinator, Combined Insurance Limited, kimberley.mackey@combined.com. 20 and Thuring 2013; Thuring et al. 2012). Toward this end, firms invest in what is usually, if somewhat loosely, referred to as “sales training” (a processual concept that often includes a blend of different teaching and learning methods). Here, both conventional wisdom (Futrrell 2005) and empirical evidence (Aberdeen Group 2012; Boehle 2010; Valencius 2009) combine to suggest that, to the extent that a sales training program is well funded and properly planned and executed, it can have a dramatically positive, if not transformative impact on sales performance, both at the individual salesperson and sales team level. Despite an emerging recognition of the strategic importance of leveraging personal selling and sales training initiatives amid the increasingly complex and competitive business environments of today (Adamson, Dixon and Toman 2012; Fogel et al. 2012; Lassk et al. 2012; Sarin et al. 2010), little research to date has considered how best to deploy the training and coaching activities that typically combine to form the basis of a salesperson introductory (i.e., “induction”) program. Yet such programs, designed for on-boarding new sales recruits, typically require a good deal of investment (Martini 2012). Moreover, when properly executed they can prove to be an invaluable source of strategic advantage. By reducing the downstream churn rate among new recruits compared with competitors, any potentially negative downstream effects associated with a loss of consistency in the quality of the customer’s buying experience can be mitigated (Callender and Reid 1993; Northern Illinois University Volume 14, Number 1 Jagodic 2012). Hence, the overall purpose of the research reported upon in this paper is to explore and profile the key training and coaching characteristics associated with an effective induction program for new sales recruits in the financial services industry. Specifically, through comparing and contrasting the induction programs used by higher and lower performing financial services companies competing directly with each other in the same marketplace, the research aims to: 1. Identify the key determinants of “best practice” when running an effective sales training program for new recruits. 2. Identify the key determinants of “best practice” when running an effective sales coaching program for new recruits. A research spotlight on the financial services industry can be viewed as both timely and appropriate for a number of reasons. Most notably, in the wake of the 2008 global financial crisis, financial services companies around the world have been facing an extraordinarily difficult strategic environment (Akinbami 2011; Heckl and Moormann 2010). Like other businesses, they have had to navigate their way amid widespread economic recession and some of the most difficult trading conditions on record (Mayer-Foulkes 2009). However, in many respects their macroenvironmental situation has been especially challenging. Under the microscope of much public scrutiny and some criticism of their operational norms, in most Western financial markets there has been a power shift towards political and regulatory bodies, all of which has led to a newly regulated external business environment (Chambers 2010; Lempka and Stallard 2013; Steel 2013). In addition, and primarily due to the Eurozone crisis, a financial power shift from “West” to “East” is currently underway, with new financial services organizations from countries such as China and South Korea further intensifying what is already an ultra-competitive and increasingly internationally competitive marketplace (Cox 2012; Gritten 2011; Hosono, Sakai and Tsuru 2009). Further, unlike many other types of businesses, within a financial services business the selling function typically integrates both horizontally and vertically across all market segments served as well as all of the various divisions or operating units of the organization (Farquhar and Meidan 2010; Steel 2013; Thuring et al. 2012). Consequently, for a financial services company, the personal selling function directly affects virtually every single customer’s buying experience (Rajaobelina and Bergeron 2009). As such, personal selling plays a uniquely crucial role within a financial service company’s overall marketing strategy. Indeed, throughout the industry it is widely regarded as being a key driver of long-term business success (Brenkert 2011; Drew, Walk and Bianchi 2013). In light of the above it is arguable that across the financial services industry of today, as companies grapple to maintain market share and seek to re-establish themselves within the turbulent “new era” of financial services marketing, an efficient and effective selling effort is more important than ever before. Thus, with these issues in mind, attention next turns to a baseline review of the literature relating to sales training and sales coaching. After this, the exploratory methodology employed in this research is explained, followed by a presentation of the research findings, conclusions, and practitioner implications. Literature Review In order to more accurately define the mix of teaching and learning methods involved in a sales induction program, it is useful to differentiate between two distinct subcomponents or categories of activities, both of which are typically employed to a greater or lesser extent: 1) a sales “training program,” and; 2) a sales “coaching program” (Lambert 2009a, 2009b). The term “training program” refers to a planned and formally organized group activity aimed at imparting information and instructions to facilitate participants’ acquisition of a required level of sales-related knowledge (Mackey 2013). The perceived importance of such training among practitioners is well documented (Steel 2013). Indeed, it is estimated that U.S. companies, for example, spend $7.1 billion annually on training programs and devote more than 33 hours per year training the average salesperson (Lorge 1998). This figure increases to 73.4 training days for an average entry-level sales representative (Kaydo 1998), and in technical markets (e.g., computers, imaging systems, and chemicals), the costs associated with the development of a single salesperson can exceed $100,000 (Dubinsky 1996; Johnston and Marshall 2009). Today more than 21 Journal of Selling ever, salespeople must have a working knowledge across numerous topics in order to meet increasing customer expectations (e.g., changes in market dynamics, business enabling technologies, and business ethics) and firms are utilizing training programs to achieve and maintain high levels of salesperson competence in these areas (Galvin 2001; Steel 2013). Moreover, many firms are using a variety of training evaluation procedures in order to gauge the effectiveness of such programs (Mackey 2013). These range from self-administered reports completed by the trainees, to informal debriefing sessions, to more elaborate calculations of enhanced sales revenue (Attia, Honeycutt and Leach 2005). Certainly, the information and feedback emanating from such evaluation procedures can be considered as central to the successful implementation of strategic organizational initiatives (Moore and Seidner 1998). However, it is noteworthy that over recent years little empirical research that ties sales training (either that which is included within an induction program or that which is carried out on an ongoing basis) to performance has been undertaken (Attia, Honeycutt and Attia 2002; Hill and Allaway 1993; Lassk et al. 2012), although managerial perceptions certainly tend to support the efficacy of such endeavors (Jantan et al. 2004). In contrast to sales training, a “coaching program” is concerned with helping each individual salesperson embark upon a journey of self-improvement within an on-the-job, results-oriented context, and through a process of ongoing one-on-one conversations and dialogue with their coach (Mosca, Fazzari and Buzza 2010; Somers 2012). Here, an analogy is often drawn between the competitive worlds of sports and business sales. Just as an athlete must compete against opposing players to win games, salespeople compete against other companies’ salespeople to win accounts (Rich 1998). As such, rather like the athletic coach, the sales manager plays a similarly critical role in developing the skills of his or her sales team. In fact, the extent to which athletic success stems from natural ability is usually unquestioned, while sales management textbooks often report the idea of the natural-born salesperson as myth (e.g., Stanton, Buskirk and Spiro 1991). 22 Many salespeople reach their full potential through effective coaching and supervision activities that involve continual guidance and feedback by the sales manager at “branch” level (Rich 1998), and practitioners widely recognize this sales coaching process to be critical to the competitive success of the firm (Agarwal, Angst and Magni 2009; Corcoran et al. 1995; Dubinsky and Barry 1982; Mosca, Fazzari and Buzza 2010; Richardson 2009). Accordingly, it is therefore surprising to note that few empirical studies into the beneficial effects of sales coaching on productivity have been reported in the literature. Interestingly however, in the wider domain of executive coaching, Olivero et al. (1997) have reported that coaching (which included goal setting, problem solving, practice, feedback, supervisory involvement, evaluation of end results, and public presentation) increased productivity fourfold over training alone. Moreover, in this particular context (executive coaching in a public sector municipal agency), the authors proposed a qualitative difference in the type of learning that takes place in training and coaching, each phase serving a unique purpose. Whereas the training provided a period of abstract learning principles, the coaching facilitated concrete involvement in a project specific to each participant’s work unit (Olivero, Bane and Kopelman 1997). Thus, in this case, some attempt was made by the authors to distinguish the objectives and outcomes of training versus coaching. Similarly, Bright and Crockett (2012) sought to evaluate the beneficial effects of a classroom-based training session followed by an individual coaching session directed at healthcare executives. The researchers reported a significant difference in an experimental group (that had received training plus coaching), compared to a control group (that did not receive training and coaching) in their ability to identify solutions to issues that positively impacted their work responsibilities, their effectiveness when under pressure, their heightened capacity to deal with changing priorities, and a greater effectiveness in dealing with tight deadlines. The experimental group also showed an increased adeptness for articulating ideas more clearly and concisely when compared to the control group. Northern Illinois University Volume 14, Number 1 In summary, a review of the literature reveals that historically, research has focused on (sales) training and coaching as discrete endeavours. Further, it seems there have been no empirical studies designed to tease out the relative contribution of each to sales performance nor has there been any research that seeks to elucidate any potential synergistic effects of training and coaching within the context of a salesperson induction program. Methodology For decades, a methodological precedent has been established whereby a variety of authors (e.g., Gardner and Levy 1955; Gill and Johnson 1991; Mintzberg 1979; November 2004; Tapp 2004; Wells 1993) have argued that the best way to study business practice is “from the inside” such that researchers get “closer to the action” and consequently gain meaningful insights into how companies go about doing what they do. This insider’s perspective typically manifests through qualitative models of research design, often inspired by interpretive, naturalistic and immersive methods (Arnould and Wallendorf 1994; Fetterman 2010; Guba and Lincoln 1994; Hirschman 1986; Lincoln and Guba 1985; Polkinghorne 1989). Accordingly, this paper reports the findings obtained from exploratory, depth interviews conducted in late 2012 and early 2013 with senior executives, at the director and vice president levels, with responsibility for business development, sales force management and sales force training in four large financial services companies. Research participants were recruited via two matched pairs of companies (one defined as “low-performing” and the other as “high performing”) competing head-tohead in seeking to serve essentially the same market(s) with a similar range of financial product/service offerings: one matched pair being located in the United Kingdom and the other in New Zealand. The use of matched pairs as the basis for a comparative study is a form of research design that is well established (cf. Brooksbank and Taylor 2007; Doyle, Saunders and Wong 1985) and was chosen because it is a model that allows for a sharp contrast to be drawn between the induction programs of higher and lower performing firms competing with one another in the same market. Note as well that per dicta of qualitative methodologies (Creswell 2003; Krueger 2008; McCracken 1988), a relatively small number of in-depth participant interactions is typically sufficient to generate enough data to ascertain the pertinent elements (i.e. the “phenomenological essence” or “core categories”) of an investigated social-psychological phenomenon. Therefore, a quest for representative “sample size” that might achieve statistical conclusion validity (i.e. an effort more germane to hypothetico-deductive research paradigms) was not pursued. The four participant companies were selected using a three-step process. The first step involved asking a knowledgeable and experienced “industry expert” in each country to compile a short list of companies to approach (two likely high performers and two likely low performers all competing against each other in the same marketplace). The second step entailed contacting these firms by telephone and email with an invitation to respond initially to a short questionnaire, with the promise that information given would be kept confidential. In essence, the questionnaire attempted to ascertain two main pieces of information: (i) the extent to which each company carried out at least some form of induction program for new sales recruits, and whether this program had exceeded, met, or failed to meet its overall objectives during the previous financial year, and; (ii) how the company had performed during the previous financial year relative to its major competitors (“better,” “the same,” “worse,” or “don’t know”) and against four specified performance measures: profit, sales volume, market share and return on investment. Notably, this type of performance measurement has been previously employed by other researchers such as Hooley and Lynch (1985) and Law et al. (1998) and although self-reported measures of relative performance have the potential to contain bias, these and other authors contend that in the absence of objective criteria, they can be both appropriate and reliable (Dess and Robinson 1984; Matear and Garrett 2004). Thus, by using the answers given in the questionnaire as a filter, the third and final step in the process involved inviting executives from one self-reported high performing company and one self-reported low performer in each matched pair (one pair based in the United Kingdom and the other based in New Zealand) to participate in a follow-up interview. 23 Journal of Selling The self-reported performance characteristics for each “matched pair” of firms are shown in Table 1. In a tact similar to Ferrell et al. (2010), subsequent depth interviews with executive participants lasted from 60 to 75 minutes each, with the scope of inquiry aimed largely at encompassing the phenomena of both broad and specific characteristics about each participating company’s planning and execution of their sales training and sales coaching induction program activities. These depth interviews were facilitated by a semi-structured, discovery-oriented interview guidelines developed in the tradition of both broad, initial “grand tour” techniques (Fetterman 2010; McCracken 1988) and more specific and acute phenomenological inquiry (Kvale 1983; Polkinghorne 1989; Rader 2007; Thompson, Locander and Pollio 1989). Interviewees steered the conversations (Morrison, Haley and Sheehan 2002) in a flexible and “informal, interactive process” utilizing “open-ended comments and questions” (Moustakas 1994, p. 114). Responses were recorded and transcribed for analysis. Selected supporting verbatim extracts are included in the body of the paper. Table 1: Self Reported Sample Performance Characteristics High Performer UK Matched Pair Failed to meet induction program Induction program objectives objectives. Performed the “same” “met.” Performed “better” than its or “worse” than major major competitors across the competitors across the measures measures specified. specified. NZ Matched Pair Induction program objectives “exceeded.” Performed “better” than its major competitors across the measures specified. Findings Best practice for running an effective sales training program In the questionnaire, all four participating companies reported that they conducted a formal, classroombased sales training program for their new recruits. The depth interviews further revealed that typically, these programs were run at least twice per year, are of 5-10 days in duration, included a cohort of 8-15 trainees, and are ideally held within the first few weeks of a new recruit’s job commencement. Indeed, in these areas there were no obvious differences between the higher and lower performers. Interestingly, however, whereas 24 Low Performer Failed to meet its induction program objectives. Performed “worse” (or “don’t know”) than major competitors across the measures specified. executives from the lower performing companies said they outsourced a trainer/instructor on an as-required basis, by contrast, it seems the higher performers prefer to use in-house trainers: one or more staff members who typically carry out this duty from time to time alongside their other functional responsibilities within corporate business development. As one executive explained: We like to use our own people, usually senior managers who have been there done that...we don’t want some off the peg, once size fits all course that’s the same as all the rest.... it’s a matter of branding, credibility and being the best. Northern Illinois University Volume 14, Number 1 When asked to identify the key objectives for their sales training program three of the four interviewees were unable to specify precise metrics. For both the lower performers, training objectives were largely relegated to the seemingly obvious need for recruits to be able to “learn how to do their new job” whereas in the case of the other higher performer, at least it was claimed that training objectives were “under review.” Perhaps this overall profile of response was somewhat surprising in light of the widely received view in learning and pedagogy theory that objectives are paramount to the success of any educational/training curriculum (Bloom 1956; Dean et al. 2012; Mager 1997). However, one executive from a high performing firm was much more forthcoming and explicit in her response to the question relating to setting training objectives. She explained that by the end of her company’s formal sales training program, all new recruits will have taken a series of tests to prove that they could recall and comprehend key information to “an acceptable level,” further elaborating: Pretty much the sole purpose of our training program is the acquisition of basic knowledge... from there, professional skills can go on to be developed and finessed. As might have been expected, one of the most important elements of an effective sales training program, according to all four interviewees, related to the need to design program content in a logical, progressive, step-by-step sequence. There was also general agreement about the key topic areas to cover, which included the following: product knowledge, industry knowledge, customer and market knowledge; the sales process (incorporating a range of selling skills, tools and techniques such as interviewing, presenting, benefit selling, closing and objection-handling); new business prospecting methods; customer service and relationship building procedures; and self-management. Nonetheless, the interviews did indicate that the higher performers were differentiated from their lower performing counterparts by their inclusion of an additional topic: the provision of a detailed understanding of the sales coaching process that was planned to follow-up and build upon the initial sales training program inputs. As one executive put it: Our recruits need to know that learning doesn’t stop when the formal training is over... they also need to understand what’s going to happen next when they get to meet their field manager and all the ins and outs of how they’re going to be managed and coached to become superstars. Interestingly, another topic highlighted by one interviewee from a higher performing company (although not by any of the others), was the need to spend sufficient time on introducing new recruits to their company’s culture. Culture was described as referring to the company’s traditions, values, beliefs, and ethics. In their own words, in short: Right from the start, every new staff member has to understand how we do things around here... it’s what defines us. This interviewee went on to explain that this part of the training program was now considered essential in the post-global financial crisis era because of the imperative for his company to strive to conduct its business to the highest possible professional standards, and to facilitate its ability to attract and retain people of excellence. Another strong theme of agreement among all interviewees related to the need to ensure that the program encompassed a wide range of delivery methods conducive to a “classroom” environment, on the basis that this serves to accommodate the many different preferred learning styles among trainees. Methods highlighted included traditional “chalk and talk” teaching alongside group discussion and brainstorming sessions, individual and group exercises, films, roleplays, online games and simulations, and such like. However, upon further questioning, it became apparent that with regard to the use and application of computer technology, the higher performers were well ahead of their counterparts. Both the interviewees from the higher performing companies explained in detail and with some enthusiasm that their companies had recently developed, or were at least currently in the process of developing, a dedicated intranet-based learning environment. The logic behind these initiatives was succinctly articulated when one executive commented: 25 Journal of Selling We’ve read the tea leaves just like everybody else. So the future is a fully integrated online-offline learning environment that promotes ongoing self-improvement, interfaces with line managers’ performance reviews, with HR, and does the whole nine yards. Thus, with specific regard to the role this system plays in the sales training room, in simple terms it provides a convenient, centrally accessible source of backup teaching and learning support materials such as course notes, fact sheets, checklists, workbooks, selfevaluation tools, video clips and so on. Its real value, however, was much more that of being an “enabling” technology (Lambert 2009a), providing a means by which each trainee’s subsequent experiences of being coached on-the-job could, over time, benefit from previous training inputs and via a process of ongoing application and evaluation, help turn them into wellhoned practical skills and behaviors. Best practice for running an effective sales coaching program In the questionnaire, the four participating companies had indicated that their company’s induction course included some form of sales coaching program. Indeed, the interviews revealed that although the term “coaching” meant different things to different companies, all four companies viewed it as a critically important “in the field” follow-up, complementary activity, to their sales training program -- and one that made up the remainder of a set induction program lasting either three months (one, lower performing company) or six months (one lower performing and the two higher performing companies). Interestingly, however, for the lower performing companies it seems that at the conclusion of this period the new recruit was deemed to have successfully “passed” their probationary period simply on the authority of their field office/branch manager. By contrast, the interviewees from the higher performing companies insisted that achieving the status of a “professional XXXXX” (read here the formal job title used by each company) was dependent upon adherence to a strict assessment procedure including, in both cases, the results of a formal customer service satisfaction survey completed by clients, together with 26 the systematic review of various written assessments and progress reports. As one interviewee asserted: It’s no cake walk. Our recruits know exactly what hoops they have to jump through before they can consider themselves to be a graduate of our academy. As indicated earlier, the interviews also revealed that the higher performing companies were differentiated from their lower performing counterparts by their depth of understanding and application of the term “coaching.” In fact, for the lower performers it was seemingly an extremely loosely defined term that merely meant their office/branch sales manager had been assigned the task of “showing a new recruit the ropes” often by taking him or her out with them on customer visits so that they could learn by “sitting next to Nellie” and/or quite simply, as one interviewee stated: It requires always being on the spot to offer further information, advice, support, guidance and so forth. In sharp contrast, an executive from a higher performing firm commented: Being a coach is not the same as being a manager. It’s a different set of skills that our managers have to learn in order that they can perform the role [of a coach] to the benefit of each new staff member. Indeed, for this high performer the coaching role might be characterized as “textbook” in that it was described by an executive to be an experiential-based, facilitated self-learning process, necessitating that the coach encourages and challenges his or her recruit to develop their own ever-evolving learning goals and sales targets. The coach here helps them to analyse, plan, implement and evaluate incremental improvements to their overall skill set as time goes by. Interestingly, it also became apparent that (at least for the company that was using its own purpose-built online learning platform), each coach was expected to post regular progress reports so that whenever a need arose for additional training on a specific topic, it could easily be spotted and a dedicated, short (half or one day) in-house training course could be arranged in a timely fashion. Northern Illinois University Volume 14, Number 1 In view of the combination of findings reported above, perhaps it was not too surprising that when the four interviewees were asked to identify the main objectives of their company’s sales coaching program, the executives from the higher performing companies were noticeably more assertive in explicating their response. For them, during the first few weeks and months of work, coaching was a means to help cultivate and develop all the necessary skills of the profession, systematically attempting to apply all the tools and techniques that had been learned in the classroom. Moreover, an important secondary objective was to develop the skills of self analysis so that each recruit was empowered to become a lifelong self-learner. As one interviewee put it: Ultimately, we want our people to be all they are capable of becoming, and more! Despite a number of clear differences in the role that sales coaching played among our four participating companies (and notwithstanding the differences in their understanding of the term itself), the interviews did reveal one commonly held perception about the nature of an effective sales coaching program. All four executives stressed that it was up to every new recruit to drive the process. For each recruit, the intrinsic motivation to want to be a success, and the willingness to accept full responsibility and accountability for making the coaching process an effective one, is paramount. Conclusions and Managerial Research This study has served to validate much of the conventional wisdom typically espoused in the literature about the nature of effective sales training (Attia, Honeycutt and Leach 2005; Ricks, Williams and Weeks 2008). In particular, the balance of the reported evidence suggests that when planning and executing a sales training program it is important to: set clear objectives that relate primarily to knowledge acquisition; employ a structured curriculum (to cover company knowledge, product knowledge, industry knowledge, market knowledge, the selling process, new business prospecting methods, customer service/ relationship building procedures, self-management, and the coaching process), adopt a timeline long enough to enable trainees to fully engage in the learning experience; employ a range of pedagogical delivery techniques that cater to varied learning styles; provide trainees with plenty of supporting documentation, and; check that knowledge transfer is actually occurring at frequent intervals throughout the program. However, a number of other key success factors have emerged that appear to be uniquely associated with the training activities of the higher performers. For example, it might well be preferable to use in-house trainers/instructors who will have credibility in the eyes of trainees by virtue of a track record of sales achievement. It might also be necessary to ensure two extra items are included in the training agenda: 1) the provision of a thorough appreciation of the importance of, and the processes involved in, the company’s onthe-job sales coaching program that typically follows as part of the overall salesperson induction period, and; 2) the provision of a thorough understanding of the company’s “culture,” especially those aspects of the company’s operations that are required to be in keeping with the customer-centric ethical standards that are widely expected to be upheld in today’s marketplace. Another distinctive dimension of the higher performers’ training activities lies in the area of technology. It seems that a purpose-built online learning environment is integral to their ability to enable each trainee, his or her line manager/coach, and others within the company, to maximize the exchange of information about progress made to the mutual benefit of all parties. The successful adoption of such computer technologies (for use in sales training programs) may also be indicative of a changing workforce, increasingly comprised of “digital natives” who feel at ease with computer-mediated learning modalities (Palfrey and Gasser 2013). The study findings have also served to validate much of the conventional wisdom typically espoused in the literature about the nature of effective sales coaching (cf. Graham and Renshaw 2005; Rosen 2008). In particular, it has highlighted the very different, yet entirely complementary, role that a sales coaching program plays when compared with a sales training program, as summarized in Table 2. Certainly, the interviews served to confirm that when running a sales coaching program, some of the basic success factors to observe include: the setting of clear objectives and especially those that relate to the 27 Journal of Selling Table 2: Key Features of Sales Training Versus Sales Coaching Table 2: Key Features of Sales Training Versus Sales Coaching Sales Training Program Sales Coaching Program Infrequent / occasional Sales Training Program Frequent / on-going Sales Coaching Program Generalized/ occasional to sales team Infrequent Individualized one on one Frequent / on-going Knowledge acquisition focus Generalized to sales team Skill acquisition Individualized onefocus on one Classroom-based learning Knowledge acquisition focus Experiential-based learning Fixed / planned agenda Classroom-based learning Dynamic / adaptive agenda Experiential-based learning Instructor - led Fixed / planned agenda Mandatory Instructor - led Shorter term goals Mandatory Salesperson - led Dynamic / adaptive agenda Voluntary Salesperson - led Longer term goals Voluntary Shorter term goals Longer term goals Skill acquisition focus cultivation of selling skills and self-appraisal; the need for a coach to be constantly questioning, encouraging and challenging their recruits to develop their own ever-evolving learning goals and sales targets and to provide them with ongoing feedback and progress reports, and; the requirement for the recruit to be a self-starter and take full responsibility and accountability for their learning as time goes by. Perhaps the most important and distinctive attribute associated with the higher performers, however, is the extent to which they have sought to properly integrate and align their sales coaching activities with their sales training activities. As the diagram in Figure 1 attempts to illustrate, it seems that the higher performers model the whole of their induction program on an underlying logic that can be directly related to, and explained by, Bloom’s (1956) taxonomy of learning domains. Figure 1: An Integrated Sales Training/Coaching Model Figure 1: An Integrated Sales Training/Coaching Model 29 29 28 Northern Illinois University Volume 14, Number 1 As Figure 1 indicates, at the outset of the induction program the new recruit requires an almost exclusive focus on basic knowledge acquisition and the ability to be able to recall that knowledge (i.e., those domains that relate to the lower levels of Bloom’s taxonomy) in order to provide a strong platform for his or her future development. Then, as time goes by and they gain on-the-job experience, sales coaching assumes an increasingly more important role in taking the salesperson to the next level (i.e., the development of selling skills through knowledge application). To put it another way, it would appear that the higher performers aim to pursue an appropriate and evolving balance of both sales training and coaching throughout the duration of their induction programs -- ideally all the way through to a conclusion which leaves the recruit capable of ongoing independent learning, having by this time reached, at least in theory, the highest levels of Bloom’s (1956) taxonomy (i.e., the skills of analysis, synthesis and evaluation). flourish within a supportive and enabling environment. Certainly, an audit of each sales manager’s ability to effectively coach their staff should be conducted, with a view to upgrading knowledge and skills as necessary. Thirdly, and perhaps most importantly, the degree to which the firm’s training and coaching activities are properly integrated and aligned requires consideration. Here it will be necessary to revise the overall objectives of the firms’ induction program. Again, using Bloom’s (1956) taxonomy of learning as a guide (see Figure 1), the aim should be to ensure that all elements of the program are geared towards encouraging new recruits to build a long term career in sales by “learning how to learn” (Argyris 1991). In pursuit of this goal, a review of the firm’s technological infrastructure is also recommended. The deployment of technology as a means of enhancing all aspects of the leaning process was found to be a key success factor that clearly differentiated the induction programs of the higher performers in our sample from those of their lower performing counterparts. These conclusions give rise to a number of implications for practitioners. It is advised that senior executives at the director and vice president level with responsibility for sales force management and training undertake a comprehensive appraisal of their firm’s salesperson induction program in order to ensure that it aligns with the key determinants of best practice identified above. In particular, attention should be focussed upon the following areas. Firstly, an evaluation of the formal “sales training” component of the firm’s induction program should be conducted. This evaluation should review all aspects of the firm’s training program, including: its stated objectives; the mix, timing and sequencing of topics covered; the range of teaching and learning activities employed, assessment procedures, and; the type of documentation and other supporting materials offered. Secondly, an evaluation of the “sales coaching” component of the firm’s induction program should be undertaken. For many managers it is envisaged that this evaluation might well reveal a need to attach more importance to the role that sales coaching plays within their firm’s induction program. In such cases it might even be necessary to question the firms’ prevailing culture with respect to salesperson learning and development since the evidence reported in this study strongly indicates that effective coaching can only Limitations and Future Research Despite the attributes of the adopted methodology, this study’s findings should nonetheless be viewed in light of a number of potential limitations. As is the case with much social-psychological research, the validity of self-reporting should be kept in mind. That is to say, when questions are used in personal interview studies, researchers are limited by the respondents’ willingness to answer such questions in a forthright manner. However, since the topics covered in the interviews were not of a sensitive nature, concern for the accuracy of the responses may be less of an issue in this case. Another limitation relates to the generalizability of the findings given the small representation of participants. If findings were to be inferred to a greater population then an additional, larger study, using quantitative methods would need to be pursued (i.e. likely surveybased research). Equally an issue meriting further inquiry relates to the generalizability of the findings to firms outside the United Kingdom and New Zealand. Although there is no reason to suspect that executives in companies outside these territories might adopt different or contrary perspectives, clearly the findings in the study might more readily impute to countries exhibiting similar social, regulatory and economic profiles. 29 Journal of Selling From an academic perspective, this study also indicates that more research into this much neglected arena is needed. For example, further qualitative research could usefully examine, in greater depth than the present study, the underlying “how-to-do–its” of effective sales coaching, including the various ways and means by which it can be best integrated and aligned with a company’s sales training activities. Equally useful would be a follow-up, survey-based (i.e., quantitative) research program designed to validate this study’s findings both within and beyond the financial services industry. Providing this research retains a practical focus it would likely prove to be extremely valuable in serving to raise standards across the sales profession, and to the ultimate benefit of customers, salespeople, businesses and society. REFERENCES Aberdeen Group (2012), “Train, Coach, Reinforce, Best Practices in Maximising Sales Productivity,” Aberdeen Group Research Library Vault. Adamson, Brent, Matthew Dixon, and Nicholas N. Toman (2012), “The End of Solution Sales,” Harvard Business Review (July-August), 61-68. Agarwal, Ritu, Corey M. Angst, and Massimo Magni (2009), “The Performance Effects of Coaching: A Multilevel Analysis Using Hierarchical Linear Modeling,” The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 20 (10), 2110-2134. Akinbami, Folarin (2011), “Financial Services and Consumer Protection after the Crisis,” International Journal of Bank Marketing, 29 (2), 134-147. Argyris, Chris (1991), “Teaching Smart People How to Learn,” Reflections, 4 (2), 4-15. Arnould, Eric J. and Melanie Wallendorf (1994), “Market-Oriented Ethnography: Interpretation Building and Marketing Strategy Formulation,” Journal of Marketing Research, 31 (November), 484-504. Attia, Ashraf M., Earl D. Honeycutt, and Magdy M. Attia (2002), “The Difficulties of Evaluating Sales Training,” Industrial Marketing Management, 31 (3), 253-259. Attia, Ashraf M., Earl D. Honeycutt, and Mark P. Leach (2005), “A Three-Stage Model for Assessing and Improving Sales Force Training and Development,” Journal of Personal Selling & Sales Management, 25 (3), 253-268. 30 Bloom, Benjamin S. (1956), Taxonomy of Educational Objectives, Handbook I: The Cognitive Domain. New York: David McKay Co, Inc. Boehle, Sarah (2010), “Global Sales Training’s Balancing Act,” Training (January), 29-31. Brenkert, George G. (2011), “Marketing of Financial Services,” in Finance Ethics: Critical Issues in Theory and Practice, John R. Boatright and George G. Brenkert, Eds. Hoboken, NJ, USA: John Wiley & Sons. Bright, Deborah and Anita Crockett (2012), “Training Combined with Coaching Can Make a Significant Difference in Job Performance and Satisfaction,” Coaching: An International Journal of Theory, Research and Practice, 5 (1), 1-18. Brooksbank, Roger and David Taylor (2007), “Strategic Marketing in Action: A Comparison of Higher and Lower Performing Manufacturing Firms in the UK,” Marketing Intelligence and Planning, 25 (1), 31-44. Callender, Guy and Kevin P. Reid (1993), Australian Sales Management. Melbourne, Australia. Chambers, Clare (2010), “Banking on Reform in 2010: Is Regulatory Change Ever Enough and Will the General Election Hold the Answers for the Financial Services Industry?,” The Law Teacher, 44 (2), 218-234. Corcoran, Kevin J., Laura K. Petersen, Daniel B. Baitch, and Mark F. Barrett (1995), High Performance Sales Organizations: Achieving Competitive Advantage in the Global Marketplace. Irwin, New York. Cox, Michael (2012), “Power Shifts, Economic Change and the Decline of the West?,” International Relations, 26 (4), 369-388. Creswell, John W. (2003), Research Design: Qualitative, Quantitative and Mixed Methods Approaches (2nd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications. Dean, Ceri B., Elizabeth R. Hubbell, Howard Pitler, and B. J. Stone (2012), Classroom Instruction That Works: Research-Based Strategies (2nd ed.). Alexandria, Virginia: Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development. Dess, Gregory and Richard Robinson (1984), “Measuring Organizational Performance in the Absence of Objective Measures: The Case of Privately Held Firms and Conglomerate Business Units,” Strategic Management Journal, 5 (3), 264-273. Northern Illinois University Volume 14, Number 1 Doyle, Peter, John Saunders, and Veronica Wong (1985), “Investigation of Japanese Marketing Strategies in the British Market,” Report to the Economic and Scientific Research Council. Drew, Michael, Adam Walk, and Robert Bianchi (2013), “Financial Product Complexity and the Limits of Financial Literacy: A Special Issue of the Journal of Financial Services Marketing,” Journal of Financial Services Marketing, 18 (3), 153-157. Dubinsky, Alan J. and Thomas E. Barry (1982), “A Survey of Sales Management Practices,” Industrial Marketing Management, 11 (2), 133-141. Dubinsky, Alan J. (1996), “Some Assumptions About the Effectiveness of Sales Training,” Journal of Personal Selling & Sales Management, 16 (3), 67-76. Ennew, Christine and Nigel Waite (2012), Financial Services Marketing: An International Guide to Principles and Practice (1st ed.). New York: Routledge. Farquhar, Jillian and Arthur Meidan (2010), Marketing Financial Services (2nd ed.). Hampshire, UK: Palgrave Macmillan. Ferrell, Linda, Tracy L. Gonzalez-Padron, and O. C. Ferrell (2010), “An Assessment of the Use of Technology in the Direct Selling Industry,” Journal of Personal Selling & Sales Management, 30 (2), 157-165. Fetterman, David M. (2010), Ethnography (3rd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications. Fogel, Suzanne, David Hoffmeister, Richard Rocco, and Daniel Strunk (2012), “Teaching Sales,” Harvard Business Review (July-August), 94-99. Futrrell, Charles M. (2005), Abc’s of Relationship Selling through Service. Irwin, New York: McGraw-Hill. Galvin, Tammy (2001), “Training Industry Report 2001,” Training, 38 (10), 40-65. Gardner, Burleigh B. and Sidney J. Levy (1955), “The Product and the Brand,” Harvard Business Review, 33 (2), 33-39. Guba, Egon G. and Yvonna S. Lincoln (1994), “Competing Paradigms in Qualitative Research,” in Handbook of Qualitative Research, Norman K. Denzin and Yvonna S. Lincoln, Eds. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications. Heckl, Diana and Jurgen Moormann (2010), “Operational Process Management in the Financial Services Industry,” in Handbook of Research on Complex Dynamic Process Management Techniques for Adaptability in Turbulent Environments, Minhong Wang and Zhaohao Sun, Eds. Hershey, PA: Business Science Reference. Hill, John S. and Arthur W. Allaway (1993), “How U.S.Based Companies Manage Sales in Foreign Countries,” Industrial Marketing Management, 22 (1), 7-16. Hirschman, Elizabeth C. (1986), “Humanistic Inquiry in Marketing Research: Philosophy, Method, and Criteria,” Journal of Marketing Research (JMR), 23 (3), 237-249. Hooley, Graham J. and James E. Lynch (1985), “Marketing Lesson from the UK’s High-Flying Companies “ Journal of Marketing Management, 1 (1), 65-74. Hosono, Kaoru, Koji Sakai, and Kotaro Tsuru (2009), “Consolidation of Banks in Japan: Causes and Consequences,” RIETI Discussion Paper, 07-E-059. Jagodic, Gregor (2012), “Effectiveness of Communication in Relation to Training of Sales Staff,” in Management, Knowledge and Learning International Conference. Celje, Slovenia. Jantan, Asri, Earl D. Honeycutt, Shawn Thelen, and Ashraf M. Attia (2004), “Managerial Perceptions of Sales Training and Performance,” Industrial Marketing Management, 33 (7), 667-673. Johnston, Mark W. and Greg W. Marshall (2009), Relationship Selling and Sales Management (3rd ed.). Irwin, New York: McGraw-Hill. Gill, John and Philip Johnson (1991), Research Methods for Managers (2nd ed.). London: Paul Chapman. Kaishev, Vladimir. K., Jens P. Nielsen, and Fredrik Thuring (2013), “Optimal Customer Selection for Cross-Selling of Financial Services Products,” Expert Systems with Applications, 40 (5), 1748-1757. Graham, Alexander and Ben Renshaw (2005), Super Coaching: The Missing Ingredient for High Performance. London: Random House. Kaydo, Chad (1998), “Should You Speed up Sales Training,” Sales and Marketing Management, 150 (10), 33. Gritten, Adéle (2011), “New Insights into Consumer Confidence in Financial Services,” International Journal of Bank Marketing, 29 (2), 90-106. Krueger, Richard A. (2008), Focus Groups: A Practical Guide for Applied Research (4th ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications. 31 Journal of Selling Kvale, Steinar (1983), “The Qualitative Research Interview: A Phenomenological and Hermeneutical Mode of Understanding,” Journal of Phenomenological Psychology, 14 (2), 171-196. Lambert, Brian (2009a), “Barriers to Appropriate Sales Training,” Training and Development, 64 (6), 22. Lambert, Brian (2009b), “Sales Training Takes Center Stage,” Training and Development, 3 (6), 62-63. Lassk, Felicia G., Thomas N. Ingram, Florian Kraus, and Rita Di Mascio (2012), “The Future of Sales Training: Challenges and Related Research Questions,” Journal of Personal Selling and Sales Management, 32 (1), 141-154. McCracken, Grant (1988), The Long Interview. Newbury Park, CA: Sage Publications. Mintzberg, Henry (1979), “An Emerging Strategy of Direct Research,” Administrative Science Quarterly, 24 (4), 582-589. Moore, Carol A. and Constance J. Seidner (1998), “Organizational Strategy and Training Evaluation,” in Evaluating Corporate Training: Models and Issues, Stephen M. Brown and Constance J. Seidner, Eds. Vol. 46. Morrison, Margaret A., J. Eric Haley, and Kim Bartel Sheehan (2002), Using Qualitative Research in Advertising. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications. Law, Kenneth S., Chi-Sum Wong, and William H. Mobley (1998), “Toward a Taxonomy of Multidimensional Constructs,” Academy of Management Review, 24 (4), 741-755. Mosca, Joseph B., Alan Fazzari, and John Buzza (2010), “Coaching to Win: A Systematic Approach to Achieving Productivity through Coaching,” Journal of Business Economics Research, 8 (5), 115-130. Lempka, Robert and Paul D. Stallard (2013), Next Generation Finance: Adapting the Financial Services Industry to Changes in Technology, Regulation and Consumer Behaviour. Hampshire, UK: Harriman House. Moustakas, Clark (1994), Phenomenological Research Methods. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications. Lincoln, Yvonna S. and Egon G. Guba (1985), “Designing a Naturalistic Inquiry,” in Naturalistic Inquiry. Newbury Park, CA: Sage Publications. Lorge, Sarah (1998), “Getting into Their Heads,” Sales and Marketing Management, 150 (February), 58-64. Mackey, Kimberley (2013), “An Investigation into the Salesperson’s Induction Program,” Unpublished Master’s Dissertation, University of Waikato. Mager, Robert F. (1997), Preparing Instructional Objectives: A Critical Tool in the Development of Effective Instruction (3rd ed.). Atlanta, Georgia: Center for Effective Performance Martini, Nancy (2012), Scientific Selling: Creating High Performance Teams through Applied Psychology and Testing. Hoboken, New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons. Matear, Sheelagh M., Tony Garrett, and Brendon J. Gray (2004), “Market Orientation, Brand Investment, New Service Development, Market Position, and Performance for Service Organisations,” International Journal of Service Industry Management, 15 (3), 284-301. Mayer-Foulkes, David A. (2009), “Long-Term Fundamentals of the 2008 Economic Crisis,” Global Economy Journal, 9 (4). 32 November, Peter (2004), “Seven Reasons Why Marketing Practitioners Should Ignore Marketing Academic Research,” Australian Marketing Journal, 12 (2), 39-50. Olivero, Gerald, K. Denise Bane, and Richard E. Kopelman (1997), “Executive Coaching as a Transfer of Training Tool: Effects on Productivity in a Public Agency,” Public Personnel Management, 26 (4), 461-470. Palfrey, John G. and Urs Gasser (2013), Born Digital: Understanding the First Generation of Digital Natives. New York: Perseus Books Group. Polkinghorne, Donald E. (1989), “Phenomenological Research Methods,” in Existential Phenomenology Perspectives in Psychology, Ronald S. Valle and Steen Halling, Eds. Vol. 41-60. New York: Plenum Press. Rader, Scott (2007), “A Phenomenological Inquiry into the Essence of the Technologically Extended Self,” in Academy of Marketing Science World Congress. Verona, Italy: Academy of Marketing Science. Rajaobelina, Lova and Jasmin Bergeron (2009), “Antecedents and Consequences of Buyer-Seller Relationship Quality in the Financial Services Industry,” International Journal of Bank Marketing, 27 (5), 359-380. Northern Illinois University Volume 14, Number 1 Rich, Gregory A. (1998), “The Constructs of Sales Coaching: Supervisory Feedback, Role Modeling and Trust,” Journal of Personal Selling & Sales Management, 18 (1), 53-63. Steel, Duncan (2013), “The Effectiveness of Integrated Sales Training and Sales Coaching within Private Banking,” Master’s Thesis, The University of Portsmouth. Richardson, Linda (2009), Sales Coaching: Making the Great Leap from Sales Manager to Sales Coach (2nd ed.). Irwin, New York: McGraw-Hill. Tapp, Alan (2004), “A Call to Arms for Applied Marketing Academics,” Marketing Intelligence and Planning, 22 (5), 579-590. Ricks, Joe M., Jacqueline A. Williams, and William A. Weeks (2008), “Sales Trainer Roles, Competencies, Skills and Behaviors: A Case Study,” Industrial Marketing Management, 37 (5), 593-603. Thompson, Craig J., William B. Locander, and Howard R. Pollio (1989), “Putting Consumer Experience Back into Consumer Research: The Philosophy and Method of Existential-Phenomenology,” Journal of Consumer Research, 16 (2), 133. Rosen, Keith (2008), Coaching Salespeople into Sales Champions. Hoboken, New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons. Sarin, Shikhar, Trina Sego, Ajay K. Kohli, and Goutam Challagalla (2010), “Characteristics That Enhance Training in Implementing Technological Change in Sales Strategy: A Field-Based Exploratory Study,” Journal of Personal Selling & Sales Management, 30 (2), 143-156. Somers, Matt (2012), Successful Coaching. London: Hodder Education. Stanton, William J., Richard H. Buskirk, and Rosann L. Spiro (1991), Management of the Sales Force. Irwin, New York: McGraw-Hill. Thuring, Fredrik, Jens P. Nielsen, Montserrat Guillén, and Catalina Bolancé (2012), “Selecting Prospects for Cross-Selling Financial Products Using Multivariate Credibility,” Expert Systems with Applications, 39 (10), 8809-8816. Valencius, Matthew G. (2009), “Better, Cheaper, Faster: Ibm Identifies Designs, Deploys and Measures Sales Training to Fit an Accelerated World,” Training and Development, 63 (June), 60-63. Wells, William D. (1993), “Discovery-Oriented Consumer Research,” Journal of Consumer Research, 19 (4), 489-504. 33