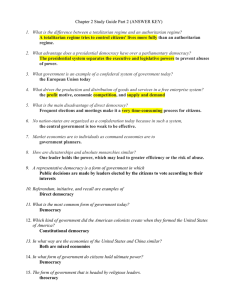

Political regime types and economic growth. UNIVERSITY OF OSLO

advertisement