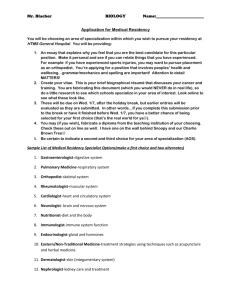

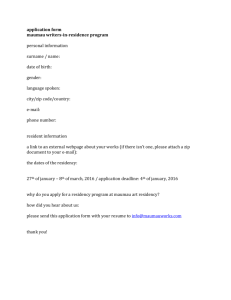

by

advertisement