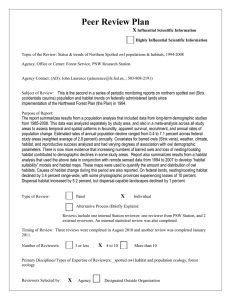

Status and Trends of Northern Spotted Owl Populations and Habitat NORTHWEST FOREST PLAN

advertisement