Chapter 3: Review of Other Quantitative Data Introduction

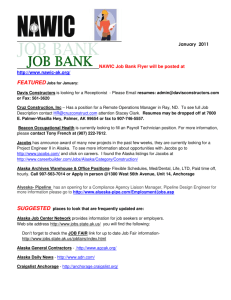

advertisement