Standard Definitions Final Dispositions of Case Codes and Outcome Rates for Surveys

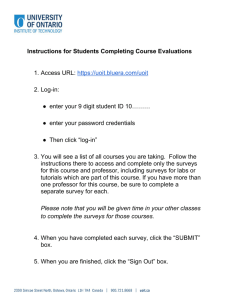

advertisement