A Habitat-Based Point-Count Protocol for Terrestrial Birds, Emphasizing Washington and Oregon

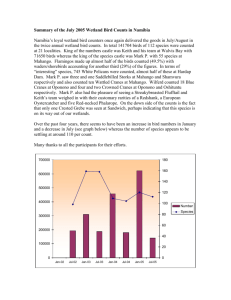

advertisement