Document 11332980

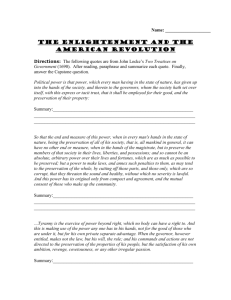

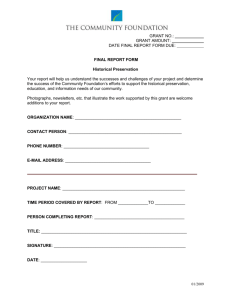

advertisement