SEE Team 3: Plants and People Introduction

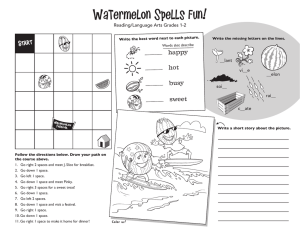

advertisement

SEE Team 3: Plants and People Dr. Michelle Nilson, Dr. David Patterson, Matthew Menzies Introduction Sustainability in higher education has been an implicit concern in international policy since 1972 (Wright, 2002) and has been an explicit concern since The Tbilisi Declaration in 1977. The Tbilisi Declaration resulted from the Tbilisi Conference, held by the United Nations Education, Scientific, and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) in cooperation with the UN Environment Programme (UNEP), and was the first international declaration that recognized the importance of environmental education in both formal and non-formal educational systems. The Declaration provided guidelines for each of the levels responsible for environmental education— local, regional, national, and international. Since that time, environmental concerns and scholarship in education have developed in three main ways. First has been an increased interest in the subject of sustainability-- either directly or indirectly through curriculum. Most notably, the field of sustainability has reached a point where the notion of a canon for sustainability has been suggested for the undergraduate curriculum in sustainability (Sherren, 2007). Second has been an increase in the study of the impact of the enterprise of education. An example of this is in the range of studies presented by the SEE Collaboration, Group 4 is examining the differential impact on resource use of on-line versus on-campus courses. This is an elaboration of several previous studies that have sought to determine the resources and environmental impact of higher education. Many of the American Association for Sustainability in Higher Education (AASHE) supported studies provide frameworks for these types of resource use analyses (see also Cole, 2003). Third has been an increase in the examination of sustainable governance of processes. These types of studies argue for sustainable leadership and education that focuses on the cultural and social aspects of educational processes. These three areas can have implications for other aspects of organizational functioning and are not entirely independent areas for study. For example, in 2000, the Canadian Association of University Business Officers (CAUBO) argued that aging infrastructure is becoming a significant concern for universities, suggesting that “aging and deteriorating facilities will have a negative impact on the ability of universities to fulfill their missions in teaching and research” (CAUBO, 2000, p. 47). A conceptual framework that was developed and tested by Cole (2003) presents the various factors that played a role in sustainability in higher education. The model was a modification of a Wellbeing Assessment that was developed earlier by Prescott-Allen in 2001. This study focuses on the People level of analysis and is specifically looking at Community and Governance issues. SEE Group 3 Report, Plants and People 2 Ecosystem Land Materials Water People Energy Air Knowledge Community Health & Wellness Governance Economy & Wealth Figure 1: Campus Sustainability Assessment Framework (Cole, 2003) Sackney (2007) argues that, “We can no longer operate from a mechanistic model where students are viewed as deficits. Instead, we need to view the educational system fundamentally as an ecological place of and for connections, relationships, reciprocity, and mutuality” (p. 2). Given the deterioration of these buildings, campus administrations are making decisions about building survival and future sustainability. But, what is not well understood is how these decisions are being made, who is involved in the decision-making process, and what happens with stakeholder input. Are there connections, relationships, and reciprocity that are currently extended, as well as being planned for in the future incarnation of the space? What are the environmental factors that community members identify as being important components of where they work and learn? And, how can administrators and those in charge of facilities work with the community to provide a sustainable environment, where the organization is as Sackney describes? The purpose of this study is to explore these questions and to understand the perceptions of four stakeholder groups within one Faculty at a large urban Canadian university about their current working and learning environments, and how they came to be where they are. We sought to explore how the values of sustainability manifest in the culture of an academic Faculty, as specifically manifest in the decision-making processes, and relationships between stakeholders and the facilities they used. We specifically focus on how culture both influences and is influenced both by community members’ perceptions of Faculty spaces, as well as by their perceptions of decision-making processes relating to the use of space. By exploring these relationships, we can gain insight into how the Faculty’s culture has been constructed and SEE Group 3 Report, Plants and People 3 interpreted by community members and their interactions, and may infer ways by which decisions can be better aligned with community members’ values towards a sustainable educational ecology. Positive engagement in working and learning spaces sustains educational organizations and suggests “how particular initiatives can be developed without compromising the development of others in the surrounding environment now and in the future” (Hargreaves & Fink, p. 17). Sustainability The primary purpose of universities is the production, application, or transformation of knowledge; their success depends largely on human relationships and creativity. While most studies of higher education sustainability focus on environmental resources and economic impacts on institutional operations, there are few studies that address the critical social indicators of sustainability (Link, 2007). In an article outlining the misconceptions of sustainability in higher education, Filho (2000) articulates four definitions of sustainable development that can be inferred to the definitions of sustainability that have emerged since the 1970s. The first is “the systematic, long-term use of natural resources” (p. 9), which is consistent with conservation movements that seek to ensure the availability of resources for those locally and nationally. The second is related to a national view of resources, “the modality of development that enables countries to progress, economically and socially, without destroying their environmental resources” (p. 10). The third sustainability is “socially just, ethically acceptable, morally fair and economically sound (here referring to the social ramifications of development)” and sustainability (p. 10); and fourth, “where environmental indicators are as important as economic indicators (here referring to the close links it bears with economic growth).” Consistent with previous work on leadership and sustainability in education (see for example, Hargreaves and Fink, 2005; and Fullan, 2005), the definition of sustainability used in this study is best characterized in Filho’s third description, where relationships and social aspects are taken into consideration. Fullan (2005) describes sustainability as, “the capacity of a system to engage in the complexities of continuous improvement consistent with deep values of human purpose” (iv). An educational organization and building that is sustainable must take into consideration the social indicators and relationships that foster a culture and organizational environment of sustainability that encourages the development of all of the participants in the community. Space and Decision Making Meusburger (2008) notes, “both in traditional and modern societies, authority structures, representations of power, distinctiveness, and differences in rank or status are to a large degree exhibited through ordering, positioning, demarcation, exclusion, and elevation” (p. 46). Day-today habits of decision-making form a reciprocal relationship with an institution’s culture, both contributing to and produced by its dynamic development. Spaces often carry symbolic significance within an institution’s culture; it is generally accepted that people often develop a strong relationship with their workspace (Cavenagh, 2005; Kuntz, 2009; Vischer, 2005). This has been described in different ways, from “a means of constructing one’s identity within a larger world” (Kuntz, 2009, p. 382) to a “non-rational attachment” (Vischer, 2005, p. 20). In a university environment that involves both working and learning spaces, many of which are shared or transient in their purpose, these spaces and what they represent to different people can SEE Group 3 Report, Plants and People 4 have significant effects on the overall workplace environment. Further, one’s workplace can be “a symbol of a [social] contractual agreement between employers and their employees that is implicitly understood and rarely questioned” (Vischer, 2005, p. 5). Cavenagh (2005) writes that “We don’t often talk about the symbolic values of spaces on campuses, and yet these values exist and have impact, as they influence the lives of students, faculty, and many others” (p. 2611). Perceptions of bias and unfairness in decision-making consequently have a detrimental effect on both individuals and the institution’s culture as a whole (Kickul, 2001). It is therefore important for decision-makers to understand the culture of the institution they are a part of. Further, Meusburger notes that “categorizing, organizing, and commanding space and controlling the spatial arrangement of persons, objects, resources, and relations are very effective devices for governing social systems and manipulating people” (p. 46); and, One should always bear in mind that the significance of the built environment and architecture “reveals itself only in combination with people and their agency” (Maran, 2006, p. 13) and, as I would like to add, in combination with their prior knowledge, experience, motives, and expectations. (p. 51) This emphasis on the interplay between governance, human agency, and (literal) structure is the primary reason that we chose to examine the decision-making processes surrounding space allocation and resources. One area in which academic institutions have to make important decisions is with respect to the shared and in-demand resource of space. Academic institutions, which are currently experiencing the effects of aging infrastructure (CAUBO, 2000) and increasing population (Schofer & Meyer, 2005), are an especially relevant context for developing understanding about space allocation decisions. Schofer and Meyer (2005) observe that the number of people associated with higher education institutions for either working or learning has grown significantly in recent decades, leading to space being termed as an “increasingly precious commodity” (Burke & Varley, 1998, p. 20). This is certainly a characteristic of the institutional subject of this case study, where more than one-third of the faculty was hired in the past five years, creating a space crunch. Method In order to investigate these process-based questions about space allocation and participant’s perceptions, we used an inductive research approach, drawing on case study methods. The case was selected based on convenience and more specifically, because there was funding provided to explore Sustainability in Education at this institution. The research team consisted of a Research Assistant, who was a Master’s level graduate student from outside the province, an Associate Dean who has been with the institution for several years and who has space allocation in his portfolio, and an Assistant Professor, who was hired three years prior to this study and was from outside the province as well. Due to the potential (and obvious) conflicts of interest, the team determined that the best person to conduct the interviews would be the Research Assistant. Further, the team determined that as the person who was responsible for allocating space, the Associate Dean would have to take on the role of participant as well as researcher. SEE Group 3 Report, Plants and People 5 The Research Assistant conducted a series of 12, forty-five minute interviews over the period of a year. Using a stratified purposeful sampling method, we sought insights from four stakeholder groups: students, staff, faculty, and administrators. We did not seek to draw any conclusions about the specific group’s experiences, but rather hoped that by investigating the process, we would learn more about the status of the current context and to explore the vision for how the future process might look. Delimitations Case studies are bound by space, time, and individuals (Creswell, 2008). This case was bound to one academic Faculty (of seven) located within one campus of a large urban Canadian university. There are four campuses in the region. Based on discussions with potential participants at the campuses, we determined that, because the experiences across each of the campuses were distinctly different, we should delimit this study to one campus-- the main one. We recognize that this delimitation is also a limitation, in that the notion of a university is fluid and is not contained to one campus—or even to a physical manifestation of a campus. In the future, we hope to explore the similarities and differences in the experiences and perceptions of the people at several campuses. Further, while there are many spaces that might be relevant to the culture of the Faculty community (even on the same campus), not all of these spaces have relevance to Faculty level administrators who are making decisions. Because our research questions focus on these decisions, we bounded our study by the space that the Faculty has control over. We sampled for maximal variation, interviewing members of the faculty community that are involved a variety of roles (including students, staff, administrators, and faculty) with the understanding that they are all part of the social construction of its culture. Each constituent’s past experiences are considered to be relevant to how the community member interacts within the community and thus is relevant to culture (Tierney, 1988a). For this reason, our study is not bound by time. Research Design As it will “serv[e] the purpose of illuminating a particular issue,” the ethnographic study we conducted can be further defined as an “instrumental” case study (Creswell, 2008, p. 476). Specifically, we explored the relationship between space, including decisions about space, and a Faculty’s culture. Our goal is to provide a lens through which an administrator might inform decisions about how spaces controlled by the Faculty are used. Data collection methods initially focused on interviews with community members in a variety of roles in the Faculty. This included note-taking by the interviewer, as well as audio recording of what was said during the interview. Recorded interviews were transcribed, and coded using inductive coding methods, and were organized into relevant themes, which are reported below. Data collection procedures Masland (1985) suggests that a more complete picture be captured by an investigation into organizational culture through the inclusion of “members of various campus constituencies such as faculty, students, administrators, and staff” in the interview sample of a study into SEE Group 3 Report, Plants and People 6 organizational culture (p. 163). His sentiments are reinforced by Tierney (1988a), who states that “it is possible for all organizational participants to influence and be influenced by an organization’s culture” (p. 10). Participants were enlisted on a volunteer basis, and were recruited in person at staff meetings, and via poster, flyer, and email notification. We interviewed a diverse sample of constituents, selecting the sample purposefully based on the differing characteristic of individuals’ respective roles within the Faculty. We interviewed 12 participants, allowing for both depth and breadth of data collection and interpretation. Adhering to Tierney’s (1991) guidelines, interviews were 45 minutes in length. They were semi-structured in order to allow for open-ended responses, while relying on a framework that focuses on developing the themes of space and decision-making that we are interested in. We also relied on other documents such as the maps of the Faculty building. We allowed for the fact that a wide variety of artifacts can emerge during interactions with Faculty community members, and left open the possibility for their collection and analysis. Instrument Chaffee and Tierney explored the cultures of several campus cultures in 1988, establishing their authority in the ‘academic ethnography’ research field. As a follow-up to this exploration, Tierney (1991) outlined a number of guidelines for researchers conducting ethnographic interviews in academic institutions. We adhered to his following suggestions in conducting interviews for this study: • • • • • Participants were met “on their turf,” preferably an office or similarly private space, in order to ensure that they were comfortable during the interview and that confidentiality was being attended to (Tierney, 1991, p. 12). A mix of recording methods, including digital audio recording and notes written both during and after the interview, were be used. We employed flexible interviewing techniques, tailored to each participant and context. We constructed targeted questions relating to “experience, opinion, feeling, knowledge, sensory, and background in order to elicit relevant information” (Tierney, 1991, p. 15). For trustworthiness, member checking was done during the interview, by summarizing what has been said and moving toward a conclusion. Tierney (1991) emphasizes that the key to the ethnographic interview process is in allowing the interviewee’s knowledge and experience to emerge, noting that “instead of manipulating the research process to fit categories already outlines, the inquirer tries to understand the participants’ worldviews” (p. 10). Research instruments To demonstrate how the interview process unfolded, the following represents types of questions that were asked, as well as potential follow-up questions. In order to allow for rich conversations that delve into participants’ relevant experiences, interviews followed this line of questioning. SEE Group 3 Report, Plants and People 7 Example question 1: What spaces do you use within the Faculty? Example question 2: How would you describe [a particular space]? Example question 3: How would you describe your feelings with respect to the process that led to you being allocated this space? Example question 4: How well does your space facilitate the activities you use it for? Participant’s answers were followed with questions and responses that encouraged discussion about feelings related to the space, interactions in spaces, and decisions leading to the community member’s use of that space. Specific follow-up questions and responses were dependent on the unique answers that were given by participants, and skill on the part of the interviewer will be required in order to effectively probe the aforementioned themes. As Tierney (1991) concisely states, “the interviewers’ adaptability and spontaneity allow for the collection of data that otherwise would be lost” (p. 10). Results Qualities of Concern: How Community Members Relate with their Spaces Physical qualities of spaces in this institution that community members are concerned about have been revealed in this study. Through forty-five minute to hour-long interviews, participants have shared their individual perspectives on what works, and what doesn’t, with respect to the spaces that they use. Among the students, staff, administrators, and faculty members interviewed, certain themes have emerged as particularly salient, which are explored in this section. Proximity to Colleagues and Resources Participating faculty members, and administrators in particular, expressed a sense of value towards their physical proximity to colleagues, resources, and also between main and satellite campuses. A faculty member, for instance, noted that he made arrangements to move his office because of a sense of isolation from colleagues and technical support. An administrator, referring to the effects of splitting members of a special programs unit between two campuses, suggests that “one of the ways mythologies happen is that if people who are involved in them can’t actually talk together, and then they start circulating.” Interviewees expressed concern about the availability of resources in the spaces they use, one suggesting that he is “more likely to book a space that has more equipment [than needed] on a given day” to avoid the hassle of having to “drag all the equipment in and tear it down again.” A graduate student who uses a shared office in her role as a sessional instructor enjoys the location of the space “in the hub of the same hallway as Undergraduate Programs, you know, just up the road from [a communal educational technology and lounge space]...and next to the bathroom, that’s nice too.” A faculty member who is situated on a satellite campus expresses a common perception in these interviews that “splitting the same faculty is a bit nuts” for a variety of reasons, including the fact that students and instructors have to move between campuses for classes; that paper documents requiring review or a signature also require a trip across town; and that important meetings tend to take place on the main campus, thus inconveniencing community members not located there. SEE Group 3 Report, Plants and People 8 Privacy is valued in this institution, as noted by community members who desire private spaces for confidential meetings, storage of confidential information, performing work without interruption, and even to simply disconnect from the environment. One current faculty member recalls that “if you had a student crying” in a former sessional instructor office space, “they were crying in front of all these people.” She continues to suggest that this issue has not been resolved, as “[while] you can close your door, it’s a glass door...also, the walls are like tissue paper here.” A staff member also expressed her desire to have her own door. Another faculty member notes his desire to hold on to a research assistant office space in part for the purpose of securely storing sensitive materials because “on all of your ethics paperwork you have to have a place to store these data and my data tend to take the form of graphs of surveys and videotapes.” He also expresses his perception that other colleagues “are very intentional about staying away from campus when they’re working on tasks that require what [he] would describe as obsessive attention” in order to avoid being interrupted in their office. The ability to have a private space to get work done was expressed in particular by a PhD student who noted that her current office space, though not particularly large or inviting, is “perfect, because it’s very, like, nothing here except me and my work.” As well, another master’s student valued the ability to eat meals and rest, even nap, in his office space. Balancing Privacy and Community Interestingly, community members often expressed ideas about community that might be seen as conflicting with the desire for privacy indicated above. They wanted communal spaces to meet people and form relationships. In this institution, there exists a large educational technology and lounge space that is referred as a “point of gathering” and a “town square” by a graduate student and a faculty member, respectively. Many have expressed concerns about recent renovations that converted part of this space into offices due to its unique purpose as a community-supporting space. Community members also expressed a desire for spaces that support learning and sharing of ideas. A PhD student, for example, discussed a shared teaching assistant space as “[giving him] a chance to actually just engage with the other TAs...and as you get to know people you get more comfortable just spinning around in your chair and going ‘hey, have you thought about this?’” Similarly, an administrator, reflecting on effective work spaces, noted that “math [referring to the mathematics education PhD cohort] basically has a...shared space where students have the opportunity to collaborate and work together on projects.” Participants want an infrastructure that supports learning - with peers, and also with faculty members. A common sentiment among all participant groups was that learning is not restricted to formal coursework and classroom spaces. A staff member noted that “when I run into people in the hallways, you learn so much from them,” and a PhD student shared that he spends “most of my time on my feet in order for the social interactions I engage in and want to engage in, as I see them as learning.” He expressed value in “getting a chance to one, learn from a modeled behaviour...and two, then to be the person that others ask.” To facilitate this kind of interaction, another PhD student recommended having more open spaces as opposed to continuing to increase the number of offices. SEE Group 3 Report, Plants and People 9 The effects of spaces that do not support these kinds of opportunities are reflected in a master’s student’s revelations that “I don’t feel much like a person in this space...I feel very much like an object walking by other objects,” particularly in reference to his observations that beyond the utilitarian, there aren’t “great spaces for friendship, great spaces for dialogue, great spaces for discussion.” A faculty member also noted that “the hallways are not - and I’m sure you’ve heard this - very conducive to collegial talk,” a sentiment shared by a PhD student who added “it’s a transitory space...people walk past it, but not through it...I’ve seen these types of dead spaces around, and they don’t allow for my type of learning.” A staff member mentioned experiences of isolation, saying, “people aren’t really here,” “no one ever sees me,” and that “the space in this building doesn’t really encourage interaction.” A faculty member notes the unique location of a satellite campus that facilitates university outreach to the surrounding community, noting that she thinks “there’s potential for growth in the Education Faculty over there, and to become an even more prominent part of the community.” She goes on to add that: The university makes intentional, um, outreach type moves to the high schools and there are designated scholarships for [students born in the local community] to come to [the local campus] so they can, they’re really trying to, because, my sense is that the demographics are such that there are a lot of, um, students in [the local community] who come from families where no one maybe has any post-secondary education, and so they’re trying to increase the possibility of those seeing themselves as someone who would come to university. The Ability to do One’s Job In addition to being near colleagues and resources, as well as having opportunities for both privacy and collaboration, participants in this study have expressed needs specific to the ability to do their respective jobs effectively in their spaces. Faculty members, as well as a PhD student who works as a sessional instructor, suggested that flexibility within a space was of great value to them. One faculty member noted that he likes the faculty’s instructional lab “because it’s a very flexible space...it works well because I can transition rapidly from a one-to-one computer activity and then have people circle their chairs without having to move from one room to another.” Another described the fact that “the furniture allows for flexibility in teaching models and styles” as “wonderful.” Referring to the spaces he uses when teaching, the graduate student remarked that: The fact that here we are in a Faculty of Education and we don’t have fixed desks, is a beautiful way for me to use particular metaphors in regard to what is in a design when I’m teaching. So I’ll have students move shit around all the time, and just point out ‘well, how do you feel now, being in rows looking at me? Let’s move into a U-shape. Things like that, and so I quite like the access to resources such as tables, chairs, and things that aren’t fixed.” The ineffectiveness of some spaces for teaching is often related to obstructions in the classroom. The same faculty member that appreciates the instructional lab’s flexibility notes that “with this architecture there are these pillars to support the concrete roof...so I’ve always faced SEE Group 3 Report, Plants and People 10 the issue of how to arrange the furniture around the pillars so you can have line of sight to all your students and so those are minimally obstructive as they can be during discussions.” Another faculty member makes a similar observation, noting, “they haven’t found storage space for [surplus furniture]...get that stuff out of there so that I can circle the chairs!” Other barriers in the classroom are less obvious. Reflecting on his teaching experiences, a PhD student poses the question “can I be an effective teacher if my students are uncomfortable in the room, or uncomfortable in the school? Because that then creates an extra barrier as a teacher that I have to now overcome.” The ability to meet effectively with others was expressed by several participants, often (but not exclusively) in reference to those in administrative roles. Often involved in meetings with other community members, one administrator noted that without a meeting space he would have to “just sort of huddle around that desk [indicates], which I think would be a bit uncomfortable and hard to be able to be hospitable.” One PhD student noted an attempt by a former director to relinquish her private office out of generosity; in the end, another office had to be found, simply because of the need for private conversation. Another PhD student, who also serves as a teaching assistant, shared that while “the students come to [her office] for the office hours, [it is] not very important to have a very big, or nice office.” Physical Characteristics of Spaces More general physical characteristics of spaces such as light, sound, air quality, and general maintenance also represent a common thread among participants’ interview responses. Light Natural light and windows with a view were consistently expressed as desired commodities across interviews, with participants using terms such as “fresh” and “bright,” and mentioning “natural light flooding in,” when describing spaces that they found to be most welcoming and functional. One PhD student described how another institution “made the majority of the grad [graduate student] spaces along the outside wall of the third floor so basically all along the windows, and they did that specifically to give them the benefit of natural light.” A staff member supports this value in her suggestion that “it would be nice if there was a way to design the space so that everyone got to see the outside” A faculty member shared that, during Faculty meetings, “I sort of always try to rush out the back or windows, you know, where you can get a little bit of a glimpse of what the sky is looking like.” One PhD student reflected this sentiment in the context of a graduate student office, where he observed, “individual grad students start kind of moving stuff, to get closer to the light.” Unfortunately, while the consensus seems to reflect a desire for natural light, many participants did not seem to have access to quality light sources. A staff member noted that in general, “this is a dark, dark faculty, like physically.” A master’s student expressed a desire for “real light, not fluorescent light...[which] is kinda cold and clinical.” A PhD student recognized that “natural lighting may not [always] be an option,” but suggested that “there are subtle ways of lighting it up in such a way that people want to be, want to reside there for awhile.” Such techniques, he says, may involve channeling large amounts of light that come in through doors at the ends of hallways through the hallways themselves, as well as the replacement of spotlighttype lamps that project light directly downwards with more diffuse backlighting. SEE Group 3 Report, Plants and People 11 Sound Community members at this institution also held quiet and private spaces in high regard. A staff member noted that “the way I work, if I need to focus I need it to be quiet.” She goes on to explain, however, that “the walls are paper-thin,” and that “for all intents and purposes when it comes to having a private conversation there is no such thing.” This sentiment was echoed by a faculty member who shared that “it was certainly my experience that there is no such thing as a private phone conversation.” Sound is not only a problem between rooms, but also within particular spaces. A PhD student described the pervasive noise emitted by the HVAC system in rooms throughout this academic institution in saying “you’ll be sitting in a room, you can’t hear someone five feet away from you in a seminar. But then 7:30 when they shut off, ‘hey, I can hear you, but we’ve already been through three hours of this.’” He notes that, as a teacher, “I’m fighting the lights and the ventilation.” The conditions of shared spaces The institution that is subject of this case study is over 40 years old, and is showing signs of its age in the physical conditions of spaces. Air quality is one concern that has been expressed by both students and administrators, with one PhD student stating that “we have the dust issue in all of the rooms...I mean, above here, you know if you go above there [indicating the ceiling], it’s a sea of dust of there,” and an administrator expressing that the common gathering space “was becoming a very dusty, a very kind of dingy, stale space.” This administrator continued by sharing efforts that were being made to mitigate this particular problem, referring to recent renovations as “bring[ing] in fresh air,” and “blow[ing] the centre out of [the space].” (Here, the participant is referring to the recent renovations, which removed all of the walls that were blocking air flow in this space.) Other concerns about the physical state of spaces include stories from Faculty members about water leaking during rainfall, rodents, and ants. A PhD student noted that carpeting has deteriorated to the point where “you take your students and you want to go sit on the floor in a circle...yeah, sometimes you don’t want to.” Discussion The kind of broad transformation that will be necessary to change the course of higher education has implications for the entire community. Decision-making processes do not take place in a vacuum; they take place in a complex environment where individuals and resources need to be considered. For example, there are community norms and ways of being that inform how decisions in a given circumstance should proceed, who should be involved or consulted, the use of information, and the timing or flow of the release of the decisions taken. In his article arguing for the critical role of higher education in creating a sustainable future, Cortese suggests that: Planners must focus as much on the education and research being done in higher education as on the physical, operational, and external community functions of the university and do so in an integrated, independent manner. This is profound. I believe that a college or university that models sustainability in all its operational functions and actions to collaborate with local and regional communities but does not involve the faculty and students as an integral part of the educational process will lose 75 percent of the value of its efforts and cannot fulfill its role in society. (p. 22) SEE Group 3 Report, Plants and People 12 Implications for Pedagogy There are several groups of students, administrators, staff, and faculty that will be able to use the findings of this study. To begin, sustainable leadership is a prerequisite for sustainable education. Students and faculty in architecture, planning, higher education leadership, or development should note that in any planned architectural renovation or design of an institution, the feedback and input of those who will or do teach, work, and learn in those spaces is a vital component of the process. In this study, there were several examples of participants making direct comments about the impact of the physical environment encroaching on or enabling pedagogical practices. For example, flexibility to manipulate the working, teaching, and learning spaces (e.g. control over lighting, sound, climate, configuration of furniture) had a positive relationship with the level of satisfaction with the spaces. Participants expressed great value in having the room or a variety of spaces available to accommodate their pedagogical and working needs rather than having the pedagogy be determined by the spatial limitations. While the physical spaces are important, it is also important to note that participants expressed that teaching and learning was not limited to the classroom. This is an important point and should be acknowledged and fostered in the planning of physical architecture of educational institutions. For example, in the present study, Participant 9 indicated that much of his learning takes place in conversations with others; and that these conversations tend to take place in spaces where he is comfortable. Several participants reported that informal hallway conversations were an important part of the development of community and their sense of well-being in the place where they worked and studied. Pedagogically, this is important to note, as the culture of an organization appears to have the potential to have a significant impact on students’ pedagogical experiences. This connection has been explored in other studies that look at the connection between campus environments and student engagement (see Kuh (2006), for example). Institutional spaces serve to create opportunities, to structure social interactions, and by doing so, educate community members about the organization’s culture. This idea should be recognized and explored amongst an institution’s community members, and to as great extent as possible, be considered in the design of an institution and institutional spaces. Several participants noted a need for a balance between offering spaces where quiet work that required intense concentration and those offering opportunities for social engagement and the sharing of ideas and interdisciplinary work. Questions for general Survey Instrument for Educational Sustainability A community that has citizens who are engaged has a much better chance of being successful in coordinating efforts and making progress towards its goals. These questions seek to determine the level of engagement with the working and learning spaces as well as the alignment between the function and form of the classroom and working environments. 1. To what extent do the spaces you use in your institution seem appropriate to the way you use them? Rate in terms of alignment between the space you use and what you do there. SEE Group 3 Report, Plants and People 13 1----------------------------2------------------------3------------------------4----------------------------5 Great alignment some alignment little/no alignment 2. On the spectrum below, how would you rate the decision-making process that led to the allocation of spaces you use? 1----------------------------2-------------------------3------------------------4----------------------------5 Fully transparent Somewhat transparent opaque 3. How would you rate your overall experience with the process of space allocation at your educational institution? 1----------------------------2-------------------------3------------------------4----------------------------5 Very satisfied Neutral Not at all satisfied 4. How would you rate the flexibility of spaces to accommodate your learning or teaching functions? Rate from fixed to flexible: 1----------------------------2-------------------------3------------------------4----------------------------5 Space is very flexible some accommodation possible space is fixed References Burke, E., & Varley, D. (1998). Space allocation: An analysis of higher education requirements Retrieved from http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/BFb0055879 Canadian Association of University Business Officers (CAUBO). (2000). A point of no return: The urgent need for infrastructure renewal at Canadian universities. Canada: CAUBO. Cavenagh, R. (2005). The faculty office revisited. Paper presented at the Proceedings of World Conference on Educational Multimedia, Hypermedia and Telecommunications 2005, 26112616. Cole, L. (2003). Assessing sustainability on Canadian university campuses: Development of a campus sustainability assessment framework. (Master’s thesis). Retrieved from the Library and Archives Canada Electronic Theses Repository. Cortese, A. D. (2003). The critical role of higher education in creating a sustainable future. Planning for Higher Education, March-May. Creswell, J. W. (2008). Educational research (3rd ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Education, Inc. Filho, W.L. (2000). Dealing with misconceptions on the concept of sustainability. International Journal of Sustainability in Higher Education, 1(1), pp. 9-19. SEE Group 3 Report, Plants and People 14 Fullan, M. (2005). Leadership and Sustainability: System Thinkers in Action. Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin Press. Hargreaves, A., & Fink, D. (2005). Sustainable leadership. San Franciso: Jossey-Bass. Kickul, J. (2001). When organizations break their promises: Employee reactions to unfair processes and treatment. Journal of Business Ethics, 29(4, Special Issue on Work), 289-307. Link, T. (2007). Social Indicators of Sustainable Progress for Higher Education. New Directions for Institutional Research, 134. DOI: 10.1002/ir.214 Masland, A. T. (1985). Organizational culture in the study of higher education. The Review of Higher Education, 8(2), 157-168. Meusburger, P. (2008). The nexus of knowledge and space. In Meusburger et al. (Eds.), Clashes of Knowledge. Sackney, L. (2007). Systemic Reform for Sustainability. Government of Saskatchewan Report, ID 12184. Retrieved from http://www.publications.gov.sk.ca/details.cfm?p=12184 Schofer, E., & Meyer, J. W. (2005). The worldwide expansion of higher education in the twentieth century. American Sociological Review, 70(6), 898-920. Sherren, K. (2007). Is there a sustainability canon? An exploration and aggregation of expert opinions. Environmentalist, 27, pp. 341-347. Tierney, W. G. (1988). Dimensions of culture: Analyzing educational institutions. Unpublished manuscript. Tierney, W. G. (1991). Utilizing ethnographic interviews to enhance academic decision making. New Directions for Institutional Research, (72), 7-22. Vischer, J. C. (2005). Space meets status: Designing workplace performance. New York, NY: Routledge. Wright, T. S.A. (2002) Definitions and Frameworks for Environmental Sustainability in Higher Education. Higher Education Policy, 15(2), pp. 105-120.