1 Submission # - 20729 ECER Network 22 – Higher Education

advertisement

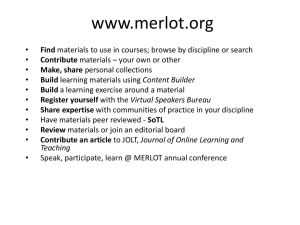

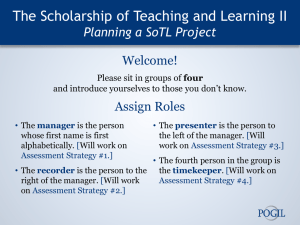

1 Submission # - 20729 ECER Network 22 – Higher Education Title: A Comprehensive Framework For Evaluating A Scholarship of Teaching and Learning Initiative In Higher Education: Successes And Challenges Authors: Cheryl Amundsen and Gregory Hum, Simon Fraser University, Canada Introduction Boyer (1990) conceptualized academic work as having “four separate, yet overlapping, functions” (p. 16): the scholarships of discovery, integration, application and teaching. The first three functions are consistent with the commonly held idea of doing research in one's field (discovery), understanding it in a larger intellectual context (integration) and applying it to problems that matter (application). Boyer argued that the scholarship of teaching should not be separate from these three functions. In other words, scholarly teaching should be founded on an understanding of knowledge development in one’s discipline, knowledge of broader pedagogical principles and practices and the use of systematic inquiry into student learning. Boyer’s notion of the scholarship of teaching and learning (SoTL) has been the catalyst for many institutions, in many countries, to develop initiatives to foster SoTL amongst academic staff (Chalmers, 2011; Hutching et al, 2002). So too has the literature relevant to SoTL grown in size and international authorship with contributions providing further definition (e.g., Kreber, 2002) and models for practice (e.g., Connolly et al, 2007; Healey, 2002; Trigwell et al, 2000). Policy efforts to promote teaching and learning tend to work at the level of the individual or the institution, with little connection between these levels, thus inhibiting change, as Trowler, Fanghanel, and Wareham (2005) have noted in the UK context. Reflective of this situation, evaluations of SoTL initiatives tend to focus either on the individual academic (Chalmers, 2011; Kember 2002) or on the departmental/ institutional level (Gray et al, 2007; Waterman et al, 2010). What is lacking is a comprehensive evaluation framework across multiple levels of an institution, making it possible to better understand impact more holistically and conclusively. There is also a lack of consistency in points of evaluation used in different studies, making it difficult to compare studies and to derive clear ‘next steps’ in the promotion of SoTL. The purpose of this paper is to describe a multi-level framework for evaluating a SoTL initiative, explain how we applied the framework, and present our initial findings. Description of the Initiative Simon Fraser University (SFU) is a mid-sized university located in Canada. The SoTL initiative described in this paper is one aspect of a broader institutional process to rethink how best to support and enhance teaching and learning. This initiative, or as we call it at SFU - the Teaching and Learning Development Grant program - is facilitated through a 2 partnership between the SFU Teaching and Learning Centre1 and the Institute for the Study of Teaching and Learning in the Disciplines2. Teaching and Learning Development Grants are awarded in amounts up to $5,000 If a faculty member so decides, they may extend this funding, and proposals for two consecutive phases of a project of up to $5,000 each may be developed at one time, with the release of funding for the second phase contingent upon completion of the first phase and submission of the final report for the first phase. The specific goals of the Teaching and Learning Development Grant program are to3: Allow faculty to identify and pursue questions about teaching and learning of specific interest to them. Focus faculty investigation on student learning. Support the systematic investigation of how the design of teaching supports learning. Enhance conversations about teaching and learning within and across academic units. Utilize faculty expertise, gained through conducting a grant project, to work with other faculty to develop grant proposals. To accomplish these goals, the process is designed as follows4: 1 Faculty attend two two-hour project proposal development workshops led by faculty who are educational researchers, faculty who have previously completed projects, and staff of the SFU Teaching and Learning Centre. At the first workshop session, those developing grants discuss their ideas with other faculty attending the workshop and workshop facilitators with the purpose of turning ideas into research questions. At the second workshop session, faculty present a draft of their proposal, receive feedback and refine the budget request. Proposal drafts are further refined on a one-to-one basis with workshop facilitators, if necessary. Proposals are funded once they meet the required criteria – this is a developmental process rather than a competitive process. In other words, any faculty member who follows the process and finalizes a proposal will be funded. The majority of projects involve teams, which could include (in addition to the project leader), other faculty members, support staff, undergraduate/graduate student research assistants, and outside technical experts. Grant recipients meet once or twice during the implementation process to share successes and challenges with each other. http://www.sfu.ca/tlc.html http://www.sfu.ca/istld 3 More information about the grants process can be found at: http://www.sfu.ca/sub/teachlearn/grants.html 4 Descriptions of completed and in-progress grant projects can be found at: http://www.sfu.ca/istld 2 3 The final report takes the form of a 3-4 page written submission or a poster presented at the annual Teaching and Learning Symposium sponsored by the Teaching and Learning Centre. Findings are shared with departmental colleagues (required) and oftentimes more widely (faculty, university events, disciplinary conferences, publications). This process promotes Boyer’s (1990) notion of teaching and learning as a scholarly activity. Our design shares many characteristics of programs at other universities that seek to promote SoTL (cf. Connolly, Bouwma-Gearhart, & Clifford, 2007; Kember, 2002). These shared characteristics are that faculty choose the questions they will systematically investigate, questions are focused on student learning, findings are used to revise or redesign teaching practice, and findings are shared close colleagues with the purpose of informing the teaching practice of others. We also have built into our design safeguards against some of the problems identified with the practice of SoTL (Chalmers, 2011; Norton, 2009). For example, the assertion that this type of research often results in educational research of poor quality because faculty trained in research methodologies suited to their disciplines often are less knowledgeable about, and less experienced with, methods suited to researching teaching and learning (Colet, McAlpine, Fanghanel, & Weston (in press); Gray, Chang, & Radloff, 2007). In our case, experienced educational researchers work with faculty to develop project proposals and to support the implementation of the project as required. As well, faculty are directly provided with at least two published research studies relevant to their project with the idea that this will connect them with the work of others who have similar interests and model the educational research process. We are also building a database of these published studies (that includes the published papers that have already resulted from a few of the funded Teaching and Learning Development projects) so that grant recipients may access this broader resource. Another, often voiced, complaint about SoTL initiatives is that the expressed goal of published research as an outcome is unrealistic for most faculty for whom disciplinary research is most highly valued. While a few (n=5) of our grant recipients have gone on to produce published papers and many have presented their findings at disciplinary conferences – these activities are completely up to them. For the purposes of our grant process, the only requirement is to share (in some form) project findings with departmental colleagues. In our experience, one’s closest disciplinary colleagues are the most likely to ‘use’ the findings to inform their thinking and teaching practice. We have, as have a few others, gone beyond the design of individual teaching and learning projects to also intentionally develop community around these projects. For example, our design situates the project in the local academic workplace (cf. Boud, 2008), involves project teams (other faculty, student research assistants), and presentation to departmental colleagues is required, as noted above. We also intentionally cultivate community across academic units (cf. Waterman et al, 2010) through the collaborative development of project proposals in the workshops sessions, interim meetings of project teams during project implementation, and drawing on the expertise of faculty who have completed projects to be co-facilitators of grant proposal development workshops. 4 Methodology and data collection As an overarching evaluation framework, we draw on Maki’s (2004) notion of building an institutional process of inquiry over time and across multiple levels of the university using a ‘cycle of inquiry’ that deepens as we come to better understand the scope of what we are evaluating, providing the opportunity for depth and emergent findings. However, whereas Maki’s focus is on student learning through the systematic consideration of curriculum, our focus is on faculty, student and institutional learning through systematic inquiry into teaching and learning by faculty. Our evaluation framework focuses on both outcome and process across three levels: individual (faculty member and student), program/department and institutional (Fanghanel, 2007). Norton’s (2009) notion of “pedagogical action research” specific to the higher education context brings these three levels together by producing research evidence at a micro level (individual projects) with the aim of dissemination to make changes at the meso (departmental) and macro (institutional) levels. Our broad purpose is consistent with that of program evaluation: to collect feedback about the process that has been put in place and the outcomes that have emerged in order to better understand and improve both (Levin-Rosalis, 2003). Level One: Individual (Faculty grant recipients and students) Faculty: At this level, we are primarily interested in documenting the learning and professional growth of individual faculty members as related to their role as a teacher and as a researcher of teaching and learning in their discipline. To inform our thinking about the aspects we want to document, we have drawn on a model of SoTL (see Figure 1) developed by Trigwell and Shale (2004) that includes three components that build upon and interact with one another: knowledge, practice and outcome. At the core of the model is teaching practice – which the authors describe as “The act of academic engagement in deliberate, collaborative meaning-making with students.” (p. 530). The outcome component “includes the results of teachers' and students' collaborative efforts … the documentation that constitutes artefacts of the teaching act, such as course outlines, evaluation results, investigation results, etc., and teacher satisfaction. All contribute to what might be made available for public peer scrutiny.” (p. 530). Taking much the same position, but coming at it first from professional growth rather than SoTL, Clarke and Hollingsworth (2002) have provided a model which conceptualizes teaching development as a constant and non-linear interplay between experimentation, knowledge/beliefs/attitudes, and outcomes (see Figure 2). Both models suggest that there are different points of entry and multiple pathways to faculty learning about teaching (McAlpine, Amundsen, Clement and Light, 2009). Engaging in a SoTL process is one of these pathways. We agree with Theall and Centra (2001) who argue that there is an “ important and necessary synergy between the scholarship of teaching and learning and the improvement of teaching” (p. 34). 5 Informed by the perspectives reflected in these two models, we are documenting faculty thinking about teaching as systematic inquiry, conceptions of the self as teacher and researcher, changing understandings about student learning, and the application of project findings to teaching practice. We also want to know the challenges and tensions they face in completing the project and if the support provided is adequate. We are accomplishing this through the analysis of submitted documents (i.e., versions of the grant proposal leading up to the final version, final reports and any conference papers or published papers), notes taken at interim meetings where those conducting projects share their impressions and challenges with others at a similar point in the implementation of their projects, and post-project interviews. Student: The Trigwell and Shale model of SoTL (2004) also includes student learning as an outcome that can be documented. In our initiative at SFU, students ‘participate’ in two ways: 1) as paid research assistants working with faculty members to conduct a project. These are usually graduate students, although two projects have employed undergraduate students. Post-project interviews are conducted with all project team members including student research assistants. In these interviews, we seek their perceptions of their experience of the project in general, what they have learned about teaching, and their experience of teamwork. 2) as members of the course/program in which the project is being conducted. Teaching and Learning Development Grant projects must focus on student learning, and every project collects feedback from students and information about student learning. Through the analysis of the final reports, we are documenting student learning that results from each project. Grant recipients have used a variety of measures to document student learning including marks on individual assignments, final marks, classroom observations, questionnaires/surveys, focus groups, and interviews. Level 2: Department/School/Faculty Local academic contexts (schools, departments) can facilitate or hinder the conduct of SoTL projects (Fanghanel, 2007) as well as conversations and collaborations that support teaching development (Quinlan & Åkerlind, 2000; Knight & Trowler, 2000). Therefore, one of the stated purposes of the grant program is to encourage more conversation around aspects of teaching and learning and to build community amongst the individuals who conduct these grant projects. Consequently, at this level, we are documenting, over time, the number of projects conducted by more than one faculty member from the same academic unit and in combination with students, consideration of project work by promotion committees, dissemination of project findings within units and cost sharing with departments and faculties to support longer-term application of project findings. Level 3: Institution At the institutional level, we are documenting increased activity related to the grant projects As a start, we are documenting the number of projects completed, the number of departments represented by these projects, the number of project collaborations across academic units and the number of those who complete grant projects who present a poster of their project at the annual university-wide Teaching and Learning Symposium. As an 6 indication of building community, we are documenting the number of grant recipients who attend the interim meetings and the number of faculty members who complete projects and agree to help facilitate proposal development workshops for other faculty. Findings to date Since March 2011, 40 projects have been funded, 14 have been completed and 26 are inprogress. We present our findings to date organized by the three levels described above. Level One: Individual (Faculty grant recipients and students) Faculty: We have conducted four post-project interviews with faculty and analyzed the final reports submitted by those four faculty members. We are in the process of building an emergent coding scheme (citation) for both the interviews and the document analysis. Here we provide some excerpts from the four interviews completed providing at least some understanding of how these faculty perceive the experience of studying their teaching and the learning of their students and what they took away from their findings that they plan to apply to their teaching. None of the faculty interviewed had previously investigated their own teaching practice or student learning in any systematic way, other than through the marking of assignments and exams, nor had they read any literature about teaching in general or in their specific discipline. One faculty remarked: I found out that research in teaching in my field is a field of study itself … because research in mathematics is something different than research in mathematics education and that is—I cannot say that was something new, I knew that before, but this was my first experience really with it. Another explained his overall feeling of the usefulness of the process: I’ve been teaching I don’t know for how long, but this investigation and the [research] techniques I learned helped me to get deeper into the [student learning] experience. In terms of what they learned that they would apply to their teaching, all four mentioned some general ‘dispositions’ as well as specific activities/processes. One faculty was surprised at how well students attended to what happened in class: And another thing—I mean this could be a little bit strange—but really it was a surprise to learn going through those surveys that what we do in the class really matters. What we say to students, that really matters, so even we don’t always have a feeling the students listen—apparently most of them do—so that was—if I can say a surprise—but a realization that kind of came from this experience. 7 The findings of one project that compared (on a number of variables) two sessions of a calculus course (both sessions having 200+ students), one taught by distance education and one face-to-face produced a number of interesting findings that could improve the distance version. However, one unexpected finding was that 83% of the face-to-face students reported watching the recorded lectures that were originally developed for the distance students and found them very worthwhile. This finding led the two faculty involved in the project to redesign the face-to-face version, as follows: So what we are going to do is we are going to ask students in the face-to-face version to watch the pre-recorded lectures before the class. Then we are not going to lecture in class, we are going discuss the topics in that lecture and pose questions/problems using clickers for students to respond. So in a way maybe we can claim—and we should claim I guess—that this new design is based on our experiences from the project. We have a feeling from reading the interviews that there is some evidence of an increasing sophistication in terms of recognizing different types and levels of student learning, but we haven’t figured out yet how to code for that. Students: We have completed three interviews with graduate student research assistants who worked on two of the four projects where we have interviewed the faculty team leaders. In this case too, we are developing an emergent coding scheme, refining it as we conduct more interviews. In terms of the learning of students who are members in the courses or programs were projects are being conducted, evidence of student learning is clear, using multiple measures, in most of the final reports. Level 2: Department/School/Faculty There is strong evidence of collaboration around these grant projects. Several projects involve multiple faculty members from within the same academic unit (10/40), and nearly all projects involve graduate student research assistants from that unit. In two cases, there has been continued support once the funding from the grant is finished. In one case, ongoing funding was given by the department chair to provide a teaching release so the initial idea investigated in the project could be expanded; in the other case, funding was provided by the Dean so the program developed through the grant project could be expanded to another department within the faculty. Level 3: Institution Four projects involve inter-departmental collaborations with faculty from different academic units and two projects involve support staff as co-investigators. As well, a number of projects have hired graduate student research assistants from the Faculty of Education because of their expertise in aspects of educational research (survey development, qualitative data analysis, etc.). Most grant recipients have attended at least one interim meeting to share their experiences in conducting the project with others; some have attended two meetings. Their evaluations of the interim meetings are very 8 positive with most indicating they found the time spent extremely valuable. Nine of the fourteen completed projects were presented in the poster session for the 2012 annual Teaching and Learning Symposium and most of the in-progress grant projects have listed this as one of their dissemination plans. Funds allocated to the grants program by the central administration has increased based on positive outcomes to date, and there is recognition that research conducted in grants must be considered for career progression decisions – although we cannot yet document if this is happening in practice. Overall: Evidence supports the notion that this initiative is a pathway to teaching development and the work that emerges can impact multiple levels, promoting useful teaching research, and raising its prominence and status. References Boyer, E. (1990). Scholarship Reconsidered: Priorities of the Professoriate. Princeton, NJ: Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching. Chalmers, D. (2011). Progress and challenges to the recognition and reward of the scholarship of teaching in higher education. Higher Education Research & Development, 30(1), 25-38. Connolly, M., Bouwma-Gearhart, J., & Clifford, M., (2007). The birth of a notion: The windfalls and pitfalls of tailoring a SoTL-like concept to scientists, mathematicians, and engineers. Innovative Higher Education, 32(1), 19-34. Gray, K., Chang, R., & Radloff, A. (2007). Enhancing the scholarship of teaching and learning: Evaluation of a scheme to improve teaching and learning through action research. International Journal of Teaching and Learning in Higher Education, 19(1), 21-32. Kember, D. (2002). Long-term outcomes of educational action research projects. Educational Action Research, 10(1), 83-104. Kreber, C. (2002). Controversy and consensus on the scholarship of teaching. Studies in Higher Education, 27(2), 151-67. Levin-Rozalis, M. (2003). Evaluation and research: Differences and similarities. The Canadian Journal of Program Evaluation, 18(2), 1-31. Maki, P. (2010). Assessing for Learning: Building a Sustainable Commitment across the University. Sterling, Virginia: Stylus. McAlpine, L., Amundsen, C., Clement, M., & Light, G. (2009). Challenging the assumptions of what we do as academic developers. Studies in Continuing Education, 31(3), 261-280. 9 Norton, L. (2009). Action Research in Teaching and Learning. A Practical Guide to Conducting Pedagogical Research in Universities. Abingdon, UK: Routledge. Rege Colet, N., McAlpine, L., Fanghanel, J., & Weston, C. (in press). La recherche liée à l’enseignement au supérieur et la formalisation des pratiques enseignantes: le concept du de SoTL. N° 65 revue Recherche et Formation. Theall, M., & Centra, J.A. (2001). Assessing the scholarship of teaching: Valid decisions from valid evidence. New Directions for Teaching and Learning, 86, 31-43. Trowler, P., Fanghanel, J., & Wareham, T. (2005). Freeing the chi of change: the Higher Education Academy and enhancing teaching and learning in higher education. Studies in Higher Education, 30(4), 427-444. Waterman, M., Weber, J., Pracht, C., Conway, K., Kunz, D., Evans, B. (2010). Preparing scholars of teaching and learning using a model of collaborative peer consulting and action research. International Journal of Teaching and Learning in Higher Education, 22(2), 140-151. 10 Figure 1. Components of a model of scholarship of teaching (Trigwell & Shale, 2004, p. 530) 11 Figure 2. Professional growth (Clarke & Hollingsworth, 2002, p. 962)