Hobbes’ redoubt? Toward a geography of monetary policy Article

Article

Prog Hum Geogr OnlineFirst, published on January 28, 2010 as doi:10.1177/0309132509353817

Hobbes’ redoubt? Toward a geography of monetary policy

Progress in Human Geography

1–25

ª The Author(s) 2010

Reprints and permission: sagepub.co.uk/journalsPermissions.nav

10.1177/0309132509353817 phg.sagepub.com

Geoff Mann

Simon Fraser University, Canada

Abstract

This paper undertakes three tasks: (1) to consider monetary policy’s role in contemporary capitalism and state governance; (2) to introduce the fundamentals of contemporary monetary policy; and (3) to outline some of the material and ideological stakes in the social, political, and economic geographies of monetary policy and central banking as practised in advanced capitalist nation states. I focus on subnational and class effects, arguing that the precarious relation between central banks and national democratic processes has become increasingly tenuous. Empirical examples are drawn from Canada and the USA.

Keywords

Bank of Canada, central banking, democracy, distribution, Federal Reserve, monetary policy

I Introduction

The First World debt crisis that began in late summer 2007 unsettled even dyed-in-the-wool celebrants of laissez-faire . As former chair of the

United States Federal Reserve Alan Greenspan admitted, ‘I discovered a flaw in the model that

I perceived is the critical functioning structure that defines how the world works’ ( Guardian

24 October 2008). ‘I no longer believe in the market’s self-healing power’, said Josef Ackermann, CEO of Deutsche Bank ( Financial Times

26 March 2008). The financial meltdown forced both men to turn red-faced to the state and confess their sins. Moreover, although their recantations came at a moment that highlighted the state’s purpose particularly emphatically, both implicitly acknowledge that even in ‘normal times’ it is essential to contemporary capitalism.

But it is not a monolithic ‘State’ that has taken up the reins. On the contrary, the state has mobilized in a very particular way to confront the crisis. In the global North, responsibility has to a significant extent fallen to, or been appropriated by, central banks and the monetary policy they formulate. The events of the last two years have powerfully reminded us of the power of contemporary central banks, and the absolute centrality, even dominance, of monetary policy in the modern state’s regulatory arsenal. This situation, of course, is not entirely novel; central banks and their monetary policies have long helped shape the operation of capitalism. But the recent meltdown has clarified the range and volume of resources available to institutions like the US

Federal Reserve (the ‘Fed’), the Bank of

England, and the European Central Bank, as well as the extraordinary prerogative with which these resources are allocated. In 18 months, trillions of dollars of ‘liquidity’ was mobilized by central

Corresponding author:

Department of Geography, Simon Fraser University, 8888

University Drive, Burnaby, BC V5A 1S6, Canada

Email: geoffm@sfu.ca

1

2 Progress in Human Geography banks in their usually underemphasized role as

‘lender of last resort’, the reassuring and necessary backstop for capitalism’s inherent volatility. The necessity of such regulatory frameworks to modern capitalism stands as the most embarrassing empirical objection to any case for ‘unfettered’ markets and the ‘rolling back’ of the state. The state’s monetary authority is contemporary capital’s invisible infrastructure, the skeleton that keeps it upright when its muscles have failed.

Few geographers would deny the ‘enormous power’ of modern monetary policy (Harvey,

2006: 68) – and of its neoliberal variants in particular (Epstein, 1992; Posen, 1995; Helleiner,

2005; Pollin, 2005; Krippner, 2007). Central banks try to control the supply and value of money in the state, and, insofar as there is a geography of money or even an economic geography, they are shaped in important ways by monetary policy. Even a cursory glance reveals its uneven spatiality and its political economic significance. Take two examples. First, with the crucial exception of the European Union, monetary policy is formulated at the national scale, as if the nation were one smooth, clearly bounded political economic space. Yet, if there is one lesson economic geography teaches, it is that political economic space is neither smooth nor clearly bounded. One might therefore expect the operation of monetary policy to be significantly uneven across, say, different regions within a nation, as a few economists have found (Scott,

1955; Garrison and Chang, 1979; Jackson,

1998; Carlino and DeFina, 1998; 1999; Di

Giacinto, 2003; Rodrı´guez-Fuentes and Dow,

2003; Fielding and Shields, 2006; Dow and

Montagnoli, 2007). Second, even those who emphasize money’s tendency to ‘deterritorialize’

– a group eclectic enough to include Deleuze and

Guattari (1983: 197) and Cohen (1998) – recognize that the spatial circulation of domestic currency is nonetheless part of what defines the modern nation state’s territoriality (Gilbert,

2005). Monetary policy is the principal means by which states regulate the value and velocity of this circulation, thus helping produce state space (Helleiner, 1999).

Yet geographers have rarely examined these dynamics, despite much attention to closely related problems: money and finance, exchange rate regimes like Bretton Woods, multilateral agencies like the IMF, and monetary union in

Europe (eg, Corbridge, 1993; Leyshon and

Thrift, 1997; Tickell, 2000; Gilbert, 2005; and the edited volumes Corbridge et al ., 1994;

Martin, 1999). Cameron’s (2006; 2008) recent work on the ‘fiscal state’, and Hamnett’s

(1997) on uneven social and spatial distribution via tax cuts, are excellent models of what policyfocused geographical inquiry can do, and there is no reason why monetary policy would not benefit from the same spirited investigation.

This article tries to make some sense of the geographic work monetary policy does, and show how an attention to monetary policy matters to human geographers across the subdisciplinary range. Through a (non-technical) explanation of some ‘technical’ aspects of monetary policy, and of the spatial-distributive relations they help constitute, my objective is to introduce the main institutions, tasks, and questions in contemporary monetary policy and to identify some of their underappreciated political, social, and economic geographies. I also initiate a rough theoretical account of the ways in which recent developments in monetary policy and theory relate to the institutional and ideological infrastructure of capitalist democracy and national geography, a relation I argue is increasingly Hobbesian, non-democratic, and absolutist.

The discussion has three parts. The first

(section II) introduces the problem of monetary policy, and the principal dimensions of central banking and monetary policy of interest to human geographers. It describes the main threads of existing analyses (principally from economics) to introduce those new to the subject, and to provide a framework with which to identify problems inviting more geographically

2

Mann 3 sophisticated investigation. Section III lays out some material implications of the issues described in section II. I focus on distributional questions in particular – ie, the uneven class and regional geographies produced, maintained, and sometimes obscured by the structure and conduct of monetary policy in contemporary capitalism. Drawing mostly from Canadian and

US examples, I emphasize intranational concerns because they are crucially shaped by monetary policy, and because (with the notable exceptions of Corbridge, 1994, and Harvey,

1999: 247–51, 306–309) the sparse attention geographers have given monetary policy generally emphasizes international effects on capital flows and value chains (eg, Leyshon and Thrift,

1997).

1

Section IV concludes with some reflections on the Leviathan that haunts the geography and politics of modern monetary policy and central banking.

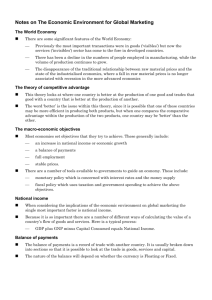

II Central banking and monetary policy

Neoliberalism – the multiscalar efforts to construct a regime in which the movement of capital and goods is determined as much as possible by firms’ short-term returns – has profoundly affected macroeconomic policy (Peck and

Tickell, 2002: 389; Peck, 2004: 402–403;

Harvey, 2005: 54, 123). As policy goals change, so too do the relations between and relative contributions of each of the three main policy realms

– ie, monetary, fiscal, and incomes/prices (Acocella, 1998; Peck, 2001; 2004). From the 1970s to the present – variously theorized as a shift from Fordism to flexible accumulation (Harvey,

1990; Hayter, 2000), accelerating neoliberalization (Peck and Tickell, 2002) and/or financialization (Krippner, 2005; Blackburn, 2006;

Arrighi, 2007; Erturk et al ., 2007) – monetary policy rose to pre-eminence in the policy suite of most powerful capitalist states, relegating fiscal policy to secondary status, and incomes and prices policy to a distant third place (Arestis and

Sawyer, 2005: 10; Krippner, 2007: 486; de

Resende and Rebei, 2008).

At its most basic, monetary policy as currently practised involves state regulation of domestic monetary dynamics by a relatively autonomous, state-affiliated central bank. Central banking has changed a great deal since fiat currencies replaced the gold standard in Europe and North America in the interwar years, but despite international variation the fundamentals have remained basically the same since that time. First, a central bank manages the value of national currency. Second, it is the ‘bankers’ bank’, and serves as the ‘lender of last resort’ in times of financial crisis. Conventionally, these two operations constitute the sphere of monetary policy per se . One further responsibility, oversight of the domestic financial sector, is the area of greatest variation. For example, while the Fed has significant regulatory responsibility, neither the Bank of Canada nor the

Bank of England oversees financial regulation

(the jurisdiction of separate bureaucracies).

Today it is accepted wisdom among central bankers that in overall macroeconomic strategy, fiscal policy should serve monetary policy (eg,

Mishkin, 2007: 38; cf. Allsopp and Vines,

2005; Krugman, 2005; de Resende and Rebei,

2008), which should take the clear lead, prioritizing the health of its ‘special’ constituency, finance capital (Bernanke, 2007: 66). Indeed, many economists – including current Fed chair

Ben Bernanke (2000) – believe the Depression of the 1930s reached its depths largely because of a lack of monetary policy response – ie, the

Fed failed adequately to undertake its lenderof-last-resort responsibilities to the banking system (Friedman and Schwartz, 1963: 299–305;

Eichengreen, 2008). Consequently, in marked contrast to the 1930s, the first and most substantial responses to the subprime crisis were coordinated by monetary authorities and targeted the financial sector alone, the leading role of the central bank and finance legitimized by the fact that a continued dearth of liquidity (a ‘credit crunch’) paralyses the capitalist economy.

3

4 Progress in Human Geography

To understand how monetary policy’s power shapes contemporary spatial political economy, this section outlines the function of central banking and monetary policy in ‘normal times’ – ie, the principal elements of everyday central banking operations in the affluent global North for the decade and a half prior to the subprime crisis of 2007 (the exceptional operations undertaken since the onset of the crisis deserve another paper). I focus on: (1) central bank operations and monetary policy instruments; (2) central bank control and decision-making systems; and

(3) policy objects and objectives. In practice the categories impinge on each other, but the distinctions usefully highlight the key spatial and social-political distributional implications. I emphasize those dimensions of monetary policy relating to the distribution, institutional structure, and political constitution of social power, because geographers can bring a particular attentiveness to monetary policy’s political effects across differentiated time and space, something economists generally do not do (Lee, 2002).

While economics has quantitatively analysed some distributive effects of central banking and monetary policy, geographers have the capacity not so much to ‘add space’ as to fill the gaping qualitative hole in the analytical donut.

2

As such, although the ideas presented in this section are challenged in sections III and IV, they are important starting points.

1 Central bank operations and policy instruments

Let us begin with the problem of what monetary policy can and cannot do. The mainstream is undecided. There is a persistent tension between economists’ and central bankers’ frequent assertions, on the one hand, that the expert conduct of monetary policy is the essential stabilizing force in modern capitalism (hence former Fed Chair

Alan Greenspan’s coronation as ‘The Maestro’;

Woodward, 2000) and, on the other, that monetary policy is a blunt and increasingly constrained instrument from which we should not expect too much (Epstein, 1992: 1–2). As Milton Friedman once noted, this contradiction does a good job of deflecting criticism:

In years when things are going well, the [Fed’s annual reports] emphasized that monetary policy is an exceedingly potent weapon and that the favorable course of events is largely the result of the skilful handling of this delicate instrument by the monetary authority. In years of depression, on the other hand, the reports emphasize that monetary policy is but one of the many tools of economic policy, that its power is highly limited, and that it was only the skilful handling of such limited powers as were available that averted disaster.

(Friedman, 1962: 233)

The power of this discursive ambivalence persists.

3

Part of the problem lies in the fact that central banks’ ultimate policy objectives are beyond their control – for example, a bank interested in stabilizing inflation at a particular rate cannot itself fix that rate – so operations can only influence ‘proximate’ targets. Over the years the targets of choice have varied, but the proximate target of virtually all central banks today is short-term interest rates, which they affect by manipulating a nominal interest rate they can determine by fiat. In all cases, the rate in question is for some essential form of short-term financing, denominated in domestic currency and essential to the everyday operation of the financial system. The interest rate of choice and the means by which it is manipulated depend upon national institutional and financial structures. For example, the Bank of Canada targets the rate on one-day lending between participants in the domestic financial sector, known as the

‘overnight rate’; the Fed targets the ‘federal funds rate’, the interest rate on funds held by member institutions to meet their reserve requirements (the portion of their liabilities they must by law keep in reserve). Assuming sufficiently accurate and tractable economic forecasts and models, the central banker

4

Mann 5 anticipates the effects of an interest rate change, and adjusts to effect a range of possible ultimate policy objectives, like exchange rate stabilization, unemployment reduction, and so on (more on this below; see Fortin, 1996; Wray, 2007;

Epstein, 2008; Braunstein and Heintz, 2008;

Cordero, 2008; Lim, 2008). In practice, however, not all ultimate objectives are considered equally worthy. In our anti-inflationary era, using interest rates to keep inflation low and stable is often treated as the essential purpose of modern monetary policy. This has significant spatial and distributional implications which are intimately tied to the politics of the theory of monetary policy, and the ambivalence regarding what monetary policy can or cannot do. As discussed in more detail in section II(3) and section

III below, both monetary policy’s purported powerlessness to direct intranational flows and the choice of inflation as ultimate policy object are legitimized by reference to monetary policy’s structural limitations – ie, its dependence on interest rate operating procedures.

These operating procedures are supposed to work like this: if inflation appears to accelerate, pushing interest rates up should slow things down by subduing consumers’ and producers’ demand for credit; if the economy is deemed too sluggish, lowering interest rates should stimulate investment and consumer demand. The particular instruments any one central bank uses to affect the interest rate of choice are determined by history, institutional structure, statutory obligations of monetary authorities and the financial sector, and the nature and degree of national capital market liberalization. Nevertheless, some basic features are generalizable. Much of a central bank’s power in the industrialized world derives from its power to ‘create its own liabilities’ (Laidler and Robson, 2004: 34) in the form of ‘high-powered money’, and from its regulation of the payments and/or reserve system, key means through which banks settle debts with each other or with the central bank. Consequently, most monetary policy actions fall into two broad categories: (1) exercising its position as the ‘bankers’ bank’, lending to and accepting deposits from the financial sector at rates the central bank determines by fiat; and (2) central bank participation in the market for domestic government securities, of which it is usually the largest holder.

a The bankers’ bank.

The central bank’s role as the bankers’ bank derives from its access (at least theoretically) to an unlimited supply of highly liquid reserves. The power of this function manifests itself in two ways. First, the central bank is the ‘lender of last resort’, the ultimate backstop for the financial system in times of crisis. This is arguably the key role played by the Fed since the onset of the subprime crisis: from August 2007 to April 2009, its balance sheet grew from US$869 billion to just over US$2 trillion, or 130 % , peaking at

US$2.3 trillion in December 2008 (Board of

Governors of the Federal Reserve, 2009:

Table 10; Federal Reserve Bank of New York,

Markets Group, 2009: 27). Second, because it is usually the sole intermediary in one or more essential interbank lending markets, the central bank influences the interest rate at which banks lend money to each other. The normal functioning of the modern financial system leaves some banks debtors and some creditors at the end of each day; debtors’ obligation to pay creditors, hold mandatory ‘settlement balances’, or meet reserve requirements forces some to borrow money for very short periods of time (hence the term ‘overnight rate’).

Since the central bank sets its own short-term deposit and loan rates, it effectively sets a floor and ceiling on systemwide rates. No creditor bank will lend money if it can get a better return by depositing with the central bank, and no debtor bank will borrow from other banks if they can get cheaper rates from the central bank. In

Canada and Sweden, where banks have no minimum reserve requirements, this work is performed within the payments system, but the

5

6 Progress in Human Geography process is similar where member banks must keep reserves with the central bank representing a proportion of the value of certain types of liabilities. In the USA, for example, by setting a rate at which funds are available to those short of their reserve requirements, and intentionally undersupplying reserves to encourage a private market in federal funds – the so-called ‘structural deficit’ – the Fed attempts to keep interbank rates inside a narrow band.

b Open market operations.

No interest rate policy performs its job perfectly. Because central banks cannot fix a target interest rate by fiat, but only their own operating band, if the market rate does not immediately settle at the target rate

(which is almost always the case), moving rates in the desired direction requires additional work.

This additional work mostly takes the form of

‘open market operations’, or OMOs – central bank participation in financial markets, usually for domestic government securities.

4

OMOs have two simultaneous and mutually reinforcing effects. First, they have a short-term effect on systemic liquidity. If central banks sell securities to financial intermediaries, systemic liquidity is temporarily reduced, since purchasers buy these bonds with high-powered money the central bank receives and ‘removes’ from circulation.

Conversely, when the monetary authority purchases securities from market participants, it transfers liquidity from the central bank to the financial system. It is important to note that changes in systemic liquidity are not limited to the value of the securities exchanged. If financial intermediaries are depository institutions, the amount of money removed or supplied to the system will be greater by some multiple reflecting the ratio of holdings to total assets and liabilities; for instance, if reserve requirements are 10 % of assets, then a million-dollar reduction in reserves means a 10 million-dollar reduction in lending.

Second, OMOs are the principal means through which central banks influence interest rates other than the target rate, since they have a direct impact on the yield of government securities, and consequently on the term structure of interest rates, or the ‘yield curve’.

5

A bond’s yield is an ‘implicit’ interest rate, the percent difference between purchase price and face value: lowering the price of a bond increases its yield, raising its price decreases its yield. Since bonds are often traded several times before they mature, yields can vary while they are outstanding (before they mature), but the initial yield determined at auction is crucial.

For some clarity, take a financially fanciful but mathematically simple example. When the central bank wants to buy or sell bonds to increase or decrease liquidity, it must do so at prices that attract sellers or buyers. If the Bank of Canada sells, for 80 dollars, a bond redeemable for 100 dollars when it matures one year from now, the implicit annual interest rate, or yield, is 25 % : the investment will yield 20 dollars, or 25 % of the 80-dollar purchase price, in one year. But if for some reason the Bank can find no buyers at 80 dollars, it must lower the price until buyers become interested. Say this happens at 50 dollars. A 100-dollar one-year bond purchased for 50 dollars has a yield of

100 % . In other words, in purchasing the bond, the buyer is effectively lending the state money at a rate of interest of 100 % . So, in the process of increasing or reducing systemic liquidity, the central bank is simultaneously lowering or raising interest rates across bonds of various maturities: by buying securities and increasing liquidity, it pushes interest rates down; by selling securities, and decreasing liquidity, it forces interest rates up. This dynamic complements the operation of the payments system and reserve regulations, since raising and lowering the target rate has a similar effect on economic activity by increasing or decreasing the cost of capital.

Interest rates on government bonds of various maturities influenced in this manner set baseline interest rates in most countries, since they represent the rate at which the financial sector can access or lend capital in the money market.

6

Mann 7

2 Central bank control and decision-making systems

Who controls the central bank and monetary policy? How do they make decisions? Framed in terms of ‘central bank independence’ (CBI) and policy ‘rules’ versus ‘discretion’, current wisdom holds that the effectiveness of monetary policy is a positive function of (1) monetary authority’s freedom from non-central bank influence, and (2) the narrowness and predictability of central banks’ policy actions.

a Central bank independence.

When central bank autonomy first emerged as an object of analysis, the chief fear was that, without some guarantee of institutional independence, actors outside the central bank, especially elected representatives, would generate excessive inflation by manipulating monetary policy as part of the

‘political business cycle’ (Nordhaus, 1975) – ie, they would loosen credit to create a boom before elections or when otherwise expedient

(Friedman, 1962). Since the early 1980s, however, with the increasingly rapid spread of antiinflationary zeal across the planet (Corbridge,

1994), the CBI debate has revolved mostly around less ‘intentional’ monetary causes of inflation. These are commonly considered a product of so-called ‘time-inconsistency’, an essential concept in contemporary macroeconomic theory (Kydland and Prescott, 1977;

Calvo, 1978).

‘Time-inconsistency’ does not denote the fact that monetary policy operates with a long lag between the decision to raise or lower rates and the moment when any change begins to influence the economy (the Bank of Canada, for example, estimates its policy lag at 18–24 months; Desjardins Group, 2005: 27). Making policy today for economic conditions two years from now is of course difficult, but timeinconsistency arises specifically because there are evident, not merely expedient, benefits to bursts of ‘surprise’ low-level inflation, which tend to increase economic activity and reduce unemployment (Barro and Gordon, 1983: 102–

104). Efforts to increase social welfare by exploiting the trade-off between unemployment and inflation by way of expansionary monetary policy make sense (appear ‘optimal’) in the short run.

6

The problem, however, is that this strategy becomes expected by buyers and sellers of commodities, labour, capital goods, and the like, who start to calculate anticipated inflation into pricing decisions and labour contracts.

The only way for expansion to have a positive effect in such conditions, then, is if it exceeds expectations (Mishkin, 2007: 9–10). This can lead to higher and higher rates of inflation, as monetary policy must become increasingly expansive to create the desired ‘surprise’.

According to orthodox economics and economic policy-makers, the inevitable result is that any positive impact of such loose money policies, however well intended, is only short-term, and far outweighed by the negative long-term impacts of inflation, which accelerate as inflation rises (Walsh, 1995: 239). The question of

CBI arises because of consensuses among contemporary economic theorists and policymakers that: (1) governments are prone to such short-sightedness; (2) economic agents develop

‘rational expectations’ of economic change; and

(3) democracy in particular exacerbates the problem of time-inconsistency, since elected governments are more likely to try to appease the electorate by pushing unemployment below the ‘natural’ or ‘non-accelerating inflation rate of unemployment’ (NAIRU) (Alesina et al .,

1997; Drazen, 2000: 142–57).

7

The logical conclusion is that countries should have an

‘independent’ central bank to avoid or minimize these temptations. As Alan Blinder, an economist and former member of the Fed’s Board of

Governors, puts it:

[M]any governments wisely try to depoliticize monetary policy by, e.g., putting it in the hands of

7

8 Progress in Human Geography unelected technocrats with long terms of office and insulation from the hurly-burly of politics. The reasoning is the same as Ulysses’: He knew he would get better long-run results by tying himself to the mast, even though he wouldn’t always feel very good about it in the short run !

(Blinder, 1998:

55–56)

Blinder’s comments inadvertently expose an important problem with an independent central bank: the plainly non-democratic nature of a handful of ‘unelected technocrats with long terms of office and insulation from the hurlyburly of politics’ (cf. Harvey, 2006: 68). Proponents of central bank independence (which today include central bankers, orthodox economists, financial capital, multilateral institutions like the International Monetary Fund, and most economic policy-makers) assuage this concern with a distinction between ‘goal independence’ and ‘instrument independence’: ‘goal independence is the ability of the central bank to set its own goals for monetary policy, while instrument independence is the ability of the central bank to independently set the instruments of monetary policy to achieve the goals’ (Mishkin,

2007: 43). Advocates of independence argue that central banks should be goal dependent, but instrument independent. General policy goals like ‘low and stable inflation’ or ‘price stability’ can be determined in consultation with elected officials, but monetary authorities should pursue these goals without interference (Blinder,

1998; Bernanke et al ., 1999; Crow, 2002;

Woodford, 2003; Mishkin, 2007).

The goal dependence-instrument independence compromise aims to limit democracy’s time-inconsistent ‘inflationary bias’ (Drazen,

2000: 114; Laidler and Robson, 2004: 80–81), while ensuring the ‘accountability’ of monetary policy. Goals may be re-examined, the argument goes, but infrequently, perhaps with a change of government or at predetermined intervals (in

Canada, presently every five years). Proponents of CBI claim the institutionalization of nondemocratic control of the monetary regime can be compensated for by central bank transparency and accountability, which they argue will allow the public to understand its goals and judge if the bank is meeting them (Woodford, 2003).

In the global North, monetary policy-making characterized by what one might call periodic democracy – or punctuated totalitarianism – is common practice today. Goal dependence with instrument independence, with a varied commitment to procedural transparency, fairly characterizes central bank operations in, for instance,

Canada, the United Kingdom, Denmark, and

Australia. The European Central Bank (ECB), with its goal and instrument independence encoded into the Treaty of European Union, is an exception (Randzio-Plath and Padoa-

Schioppa, 2000; Baltensperger et al ., 2007: 97).

8

b Rules versus discretion.

The institutional question of who makes policy is further complicated by the question of how decisions are made. Among the most important changes in monetary policy in the last 30 years is the increasing adoption of policy rules, monetary authorities’ formal renunciation of ‘discretionary’ policy flexibility in favour of ‘pre-commitment’ to policy goals the central bank is obligated to make its first, sometimes only, priority, rendering other objectives secondary. As recently as 1990, discretion dominated the monetary policy landscape; outside of the experiment with monetarism in the late 1970s and early 1980s, central banks would historically set themselves several policy mandates, prioritizing unemployment reduction when it got too high, for example, checking the exchange rate when it moved away from optimal arrangements. Today, substantive policy flexibility is rare, and where it persists, as in the USA, it does so because of what current Fed chair Bernanke

(2003: 14) once called ‘delicate issues of communication’ (ie, public opposition to dropping the Fed’s commitment to employment), and is nonetheless severely constrained. Not every central bank has opted for rules-based targets

8

Mann 9 but, with few exceptions, central banks in powerful countries have either explicitly adopted such rules or formulate policy to control de facto targets within predetermined quantitative ranges.

Friedman put forward the original case for rules in 1968, arguing that central banks should be constrained to increasing money supply by a fixed annual percentage to prevent inflation bias.

Today, rules are justified by theories of timeinconsistency and rational expectations. According to this analysis, discretionary policy choice is particularly prone to time-consistency problems, since it prevents market participants from formulating sound expectations regarding the price level. Rules not only constrain monetary policy from excessive expansion, but only when monetary authorities make clear and credible commitments to a particular target, and the public understands that target, is the expectational spiral of time-inconsistency avoidable (Barro and Gordon, 1983).

For successful monetary policy is not so much a matter of effective control of overnight interest rates as it is of shaping market expectations of the way in which interest rates, inflation, and income are likely to evolve over the coming year and later . . .

Not only do expectations about policy matter, but, at least under current circumstances, very little else matters. (Woodford, 2003: 15)

Clear and credible commitments to a rule should thus diminish or even erase timeinconsistency, because rules make central banks’ behaviour predictable, and optimal policy outcomes (ie, the target) are the same at all times and places. As such, they ‘anchor’ market expectations: if the rule says that policy will do whatever is necessary to keep inflation at or around 2 % , and the central bank has demonstrated that it will adhere to the rule, then when inflation does rise, for whatever reason, rational producers and wage-earners will assume the blip is temporary, and refrain from pricing inflation into their contracts. The goal is to overcome the fact that ‘aggregate unemployment will fall in response to positive inflation only if the inflation is unanticipated. Perfectly anticipated monetary expansions will be reflected in higher nominal wages and prices, with no significant effect on real economic activity’ (Drazen, 2000: 114).

3 Policy objects

While the case for rules has gained favour

(Wray, 2007), it is not settled, as the case of the

Fed demonstrates. A similar situation holds concerning what policy objects such rules should specify, and what quantitative level of those objects should be targeted. Let us deal with these issues in turn.

First, monetary policy has several ‘ultimate’ policy objects it might aim to effect: real exchange rates, the output gap (the difference between actual economic activity and the

‘capacity’ of the national economy), inflation rates, or employment levels, each of which could be targeted at a range of values.

9

Central banks’ experiment with monetarism – an approach to inflation control involving the manipulation of monetary aggregates (different elements of the money supply) – beginning in the latter half of the 1970s was in effect the first policy rule. By the mid-1980s, however, monetarism had fallen from grace, since a monetary aggregate the central bank could control with any precision proved elusive (Goodhart, 1995: 72). With no legitimate alternative policy strategy, the industrial world’s central bankers were somewhat rudderless, and the search for an adequately manipulable and meaningful policy object grew urgent (Freedman, 2005: 178). The same rational expectations theories that recommended policy rules also suggested monetarists’ beˆte noire , inflation, as the only appropriate choice, since, according to the logics of timeinconsistency and the natural rate of unemployment, in the long run monetary policy could not affect real variables – ie, ‘actual’ economic variables like employment and output (Lucas, 1972;

9

10 Progress in Human Geography

Sargent and Wallace, 1975). Although monetarist methods failed, a quasi-monetarist ‘new consensus’ macroeconomics reaffirmed ending inflation as really the only positive market intervention a state could undertake (Leijonhufvud,

2001: 22; Lavoie, 2006: 177).

Many argue that the political power of finance capital guaranteed the retrenchment of monetarist anti-inflationary zeal (Posen, 1995;

Wray, 2007). Despite the fact that strong cases can be made for the equitability and effectivity of other ultimate policy goals like stable real exchange rates (eg, Frenkel and Rapetti, 2008) or employment-targeting (eg, Fortin, 2003;

Epstein, 2008), mainstream economists and policy-makers virtually unanimously defend the hegemonic rule of ‘inflation-targeting’ or IT

(Arestis and Sawyer, 2005: 7; cf. Woodford,

2003; IMF, 2006). IT central banks adopt a policy rule aimed at a predetermined annual inflation rate, commonly measured by the consumer price index (CPI).

10

Most mature IT rules target a rate of about 2 % , often the mid-point of a band of more-or-less acceptable inflation between 1 % and 3 % . The difference between monetarism and quasi-monetarist IT is that, rather than trying to control the money supply, the IT solution uses interest rates like a thermostat, heating up or cooling down economic activity to maintain the inflation target. Central bank observers argue over the extent to which targets are to be achieved at all costs (Crow, 1988), or whether IT is in fact ‘constrained discretion’

(Bernanke and Mishkin, 2007: 213–15), but in any case in IT countries the lion’s share of banks’ efforts are focused on their first priority, low and stable inflation.

Geographers of neoliberalism often list IT among paradigmatic neoliberal policies, its spread across the planet helping enable a wide variety of ‘neoliberalizations’ (Peck and Tickell,

2002: 389). As of 2008, 24 central banks had formally adopted an IT rule (seven industrialized,

17 industrializing), and 18 more were candidates, expected to adopt IT in the next three to five years (Epstein and Yeldan, 2008: 133).

Since the Bank of New Zealand, the first to adopt an IT regime, did so only in 1990, this represents a remarkable rate of policy diffusion – at least as impressive as the ‘roll-out’ of intellectual property rights and the ‘roll-back’ of capital controls, two other key planks in the neoliberal platform. Rule-based IT central banks operate in some of the planet’s most affluent and influential countries (eg, UK, Sweden, Canada,

Australia, and Israel), and in many less wealthy nations as well (eg, Ghana). Several powerful central banks that have not adopted an IT rule are widely seen as ‘implicit’ inflation-targeters.

Although the Fed’s statutory mandate remains a discretionary ‘dual mandate’ of maximum employment and stable currency, current Chair

Bernanke is a long-time proponent of inflationtargeting (Bernanke et al ., 1999; Bernanke,

2003; Bernanke and Mishkin, 2007). The ECB’s reluctance to announce inflation targets is due not to comfort with inflation but to institutional commitments to goal independence that make any rule undesirable (it has an even greater anti-inflationary orientation than most IT banks, aiming at ‘below, but close to’ 2 % ; ECB,

2008).

11

Once the priority policy object is identified, central bankers face the problem of selecting a quantitative target level. Take inflation as the relevant example (although similar challenges arise with any quantitatively defined goal). Let us say we are central bankers taking the orthodox position that an inflation-targeting rule is our best policy option. Alternatively, say we are central bankers in a country like Ghana, and our

IMF loans are conditional upon the adoption of an IT rule (Epstein, 2006). Even though we now know we are inflation-targeters, much of the difficult political work lies ahead (even if in the case of Ghana we have little room for manoeuvre). Although our goal is ‘low and stable inflation’, we have yet to define ‘low’ or ‘stable’. Is 3 % ‘low’? How much volatility does

‘stability’ allow?

10

Mann 11

The problem persists if our goal is something more aggressively anti-inflationary like the

ECB’s ‘price stability’ (Parkin, 2009: 6–11).

The standard IT target level and range – 2 % , plus or minus 1 % – aims for rates of growth and volatility in the price level very low by historical standards, but notably higher than the conventional definition of ‘price stability’ as 0–2 % inflation (Walsh, 1995: 244–50; Crow, 2002:

178; ECB, 2008). At least if the anti-inflation coalition has the power to impose their policy directive, as is the case in most of the capitalist world, one might think these definitional and policy problems resolvable by simply equating price stability with ‘zero inflation’. But ‘zero inflation’, as appealing as it might first appear to central bankers and monetary economists, is generally considered unworkable for several reasons, among them the risk of deflation, the high likelihood of failure to achieve it and a resulting loss of credibility, reduced government revenues, and the surrender of a significant source of the central bank’s stimulative power

– ie, temporary and mildly inflationary pumppriming (Lucas, 1989; Johnson, 1990).

12

Definitions of price stability therefore usually allow for some inflation, which means they also allow for some definitional instability. If price stability means something more like the ECB’s

‘below, but close to’ 2 % annual inflation, then even in the technical literature it remains unclear why at that rate of inflation prices are ‘stable’, but 2.3

% renders them ‘unstable’. (This is not nitpicking. Economists and policy-makers consider a difference of 0.3

% substantial.) The importance of these definitional politics is increased by the enormous income- and wealth-distributional variability possible within the range of 0–5 % inflation (Meh and Terajima,

2008). Mild inflation redistributes real income from creditors to debtors by reducing the real value of outstanding debt because dollars paid back to the bank are worth less than dollars borrowed. Moreover, there is little evidence that such ‘moderate’ inflation impedes growth, even at 5 % (Jackson, 1998; Fortin, 2003; Brenner,

2006; Wray, 2007; Epstein and Yeldan, 2008;

Posen, 2008).

Additionally, different rates of inflation impact sectors in uneven ways, since they vary significantly in their credit dependence and financial arrangements. For instance, manufacturing firms with debts denominated in foreign currency usually fear inflation since it lowers the value of the domestic currency, increasing costs of repayment, while commodity exporters can benefit from increased foreign purchasing power

(Helleiner, 2005: 29). In other words, inflation is rarely an unmitigated evil, but is always an element of an accumulation strategy, the effects of which vary across classes, sectors, and regions

(Frieden, 1991).

III Material geographies of monetary policy

With some more specific understanding of central banking and monetary policy, let us turn to a discussion of some of the geographic work they do in contemporary North America. Given the vast range of macroeconomic policymaking’s consequences, I limit myself to the consideration of two broad dimensions in which intranational spatial political economy is produced, reproduced, and challenged by the dynamics of modern monetary policy. In this section I discuss some material-distributive dimensions. In the fourth and concluding section, I consider some discursive-ideological issues and their meaning for the thorny problem of monetary policy’s relation to democracy. The two aspects are inseparable in practice, but a distinction is useful in a first-cut account.

Material-distributive geographies of monetary policy include the many ways in which central bank operations affect flows of value and the distribution of income and wealth across spaces and social groups in the nation. As I mentioned in the introduction, perhaps the most glaring of these are the geographical unevennesses at

11

12 Progress in Human Geography various subnational scales produced by the differential impact of the monetary policy operations described in section II(1). Although formulated as if the nation were homogenous, regional differences across a vast array of conventional variables – industry mix in terms of interest-rate sensitivity and firm size, debt levels, access to and demand for credit, labour force composition, unemployment rates, flexibility of the banking system and so forth (Carlino and DeFina, 1998;

Rodrı´guez-Fuentes and Dow, 2003) – mean that interest rate changes have uneven effects (Carlino and DeFina, 1998; 1999).

13

Consider Canada, for instance. For several decades, industrialized and financially integrated central Canada (the provinces of Ontario and Que´bec) has generated much of the nation’s aggregate economic energy. Positive and negative shocks to national economic activity are generally channelled through central Canada, and, depending upon the nature of the shift, slower to take effect elsewhere (Brady and

Novin, 2001). The Atlantic region (the provinces of New Brunswick, Nova Scotia, Prince Edward

Island, and Newfoundland), in contrast, has long had higher unemployment and trouble attracting investment (a recent energy boom – now over – temporarily altered this pattern), and is disproportionately dependent upon federal transfer payments (Day, 1989; Lefebvre and Poloz,

1996; Amirault and Lafleur, 2000). Thus, while not always knocked as hard as Ontario and

Que´bec by slumps, the Atlantic provinces are almost always slower to enjoy the benefits of a recovery. These differences are ‘anecdotally’ monitored by the Bank, but are not factored into the Bank of Canada’s formal decision-making models (Amirault and Lafleur, 2000; Crow,

2002: 77, 88; Murchison and Rennison, 2006), which analyse purely aggregate national data according to the same assumptions regarding efficient markets and rational expectations that underpin the rest of the modern theory of monetary policy (Lavoie, 2006: 177–78). Among these assumptions – though unstated – is perfect intranational factor mobility, which is belied by substantial interregional variation in inflation, credit, and labour markets, for example

(Maclean, 1994; Porteous, 1995). These decision systems are thus structurally unable to reflect the Atlantic experience, and may not adequately represent central Canada either. It is no exaggeration to say that the more peripheral the region, the more it must weather a monetary policy regime intended for a set of political economic structures qualitatively different than its own (Dow and Rodrı´guez-Fuentes, 1997).

Indeed, the Bank of Canada’s technical literature on monetary policy implementation makes no mention of subnational regional difference

(eg, Engert et al ., 2008), and its ‘workhorse’ projection model for the national economy

(Murchison and Rennison, 2006) does not contain a single equation to account for interregional variation. A distinct set of equations describes a geographically unspecified ‘commodities sector’, which might be taken to represent dynamics specific to rural Canada but, if so, it is not noted by the Bank; on the contrary, it seems intended to reflect a purely sectoral differentiation in the Canadian economy. Alternatively, one might argue that the model is based on the long-standing intuition that the Canadian economy is best represented by the metropolishinterland binary (Lefebvre and Poloz, 1996), the diversity of the latter being lumped together in the commodity sector equation set. Again, if this is the intention, it hardly seems adequate to the problem. It is perhaps worth noting that although modelling intranational variation would not be easy, the Bank’s global model works with a basic spatial differentiation between five ‘regional blocs’ in the world economy, with separate sets of equations for Canada, the USA, ‘emerging Asia’, an unspecified ‘commodity exporter’, and ‘the remaining countries’

(Lalonde and Muir, 2007). The Bank’s technical literature does not explain why a similar differentiation is not tractable for the domestic model.

12

Mann 13

Before the adoption of the IT rule, discretionary attention to unemployment allowed Atlantic concerns to register on the Bank’s principal policy radars – although, as years of complaints regarding the Bank’s anti-eastern, anti-western and anti-Que´bec biases suggest, this does not mean the problem was fully addressed

(Helleiner, 2007: 228–29; see also Passaris,

1977; Constitutional Committee of the Que´bec

Liberal Party, 1991). However, since the adoption of IT, the single-minded focus on price levels has turned Canadian monetary policy into a thermostat responsive, more than ever, to price and output levels in central Canada (Crow, 2002:

165). As such, it is often the case that the

Atlantic provinces are only just beginning to enjoy the benefits of a ‘boom’ when inflationary concerns in Ontario, Que´bec, and latterly

Alberta lead the Bank to tighten rates, or, having a similar effect, to suggest they might soon raise rates. Since monetary policy has greater effect in contraction than in stimulation (Garcia and

Schaller, 1999) – you cannot ‘push on a string’, as the saying goes – and contractions tend to hit fragile economies harder (Florio, 2005), the consequence is that both booms and busts can have the effect of leaving more politicaleconomically and spatially remote regions like the Atlantic provinces further and further behind, exacerbating existing disincentives to investment, and further encouraging businesses and workers to leave the region (Drewes,

1986). Similar dynamics have been identified in the USA (Hanson et al ., 2006), Europe

(Rodrı´guez-Fuentes and Dow, 2003: 976–77), and South Africa (Fielding and Shields, 2006).

The justification for central bankers’ studied ignorance of regional unevenness is that because contemporary monetary policy operates through increasingly mobile capital, ‘one size must fit all’ (Issing, 2001: 448).

14

Today’s central banks have no time, either technically or normatively, for subnational variation, or subregional variation in the case of the EU (Crow, 2002: 14–16;

Gros and Hefeker, 2002; Frantantoni and Schuh,

2003: 585, note 7). The implications of this variation on ‘there is no alternative’ provide a crucial insight into modern monetary policy theory and practice. Insofar as contemporary central banking is predicated upon near-perfect capital markets – without which a short-term nominal anchor could never do the work it is supposed to do, since interest rate changes will not have a similar effect economy-wide – problems in monetary policy effectiveness cannot be attributed to the policy regime, but only to the real world’s failure to meet policy’s expectations.

Ingham (2004: 149) argues that, consequently, ‘modern central banks continue to attempt ideologically to universalize social and political relations’. True, but there is more to it than that; the substitution of the logical time and space of macroeconomic modelling for real time and space constitutes a ‘real abstraction’ (Colletti,

1975: 38). Central banks not only universalize – ie, extend and homogenize – but also, and even more fundamentally, abstract social and political economic relations such that the ‘real world’ is understood as a manifestation of abstractions that are themselves derived from a prior, seemingly forgotten, hypostatization of that very real world

(cf. Colletti, 1975; Mann, 2009). Modern monetary policy-making depends upon abstraction, but insofar as its abstractions are then substituted for the world itself, these abstractions are made real, materialized in the world. The logic of monetary policy’s ‘one size must fit all’ is premised on an understanding of money and monetary relations that is only possible after the key problems have been assumed away – ie, all regional and class differences are discounted as temporary. That this logic has not been extended, beyond the limited case of the EU, to challenge the political economy of state power and national territoriality as such is perhaps testament to both the centrality of state institutions to the project of monetary governance, and the exceptional ‘suprapolitical’ status monetary management currently enjoys.

13

14 Progress in Human Geography

In this instance, real abstraction lays the groundwork for some of monetary policy’s most important spatial effects, for the task is less to make policy adequate to the specifics of intranational political economy than to produce an intranational political economy adequate to policy.

Contemporary central banking consists, among other things, in the effort to performatively rewrite a nation’s regional geography, to bring into being not merely a market (MacKenzie,

2006) but a national space like that presupposed by its theory and practice. As Cameron (2008:

1146) says of the fiscal state, monetary governance too ‘has always been a means through which the norms of state form are actively imagined, created, imposed and reproduced.

Contained within . . .

is an active and continuously renegotiated imaginary of the state and its attendant ‘‘national’’ economy’. The monetarism of the late 1970s and early 1980s is only the most glaring expression of modern monetary policy’s unspoken, sometimes unconscious, attempt to sculpt the nation in the image of a computable general equilibrium model, partly because that is what economic theory says would be best for development, but even more because monetary policy would be exceedingly effective in that geography. On these terms, intranational capital mobility is less a condition for or constraint upon monetary policy than an intended effect thereof.

Indeed, one could argue that in its hegemonic, quasi-monetarist inflation-targeting form, monetary policy hopes to function as a subnational

Rostovian modernization machine, coercing regions into fitting its model of policy effectivity.

In Canada, the UK, and the USA, for example, the central bank faces, but must nevertheless ignore, the glaring problem of differing regional inflation and structural unemployment levels. It is as if they must wish the regional disparity away, or force it out of the picture – ie, keep doing what they are doing until prices equilibrate, labour markets become more flexible

(wages in low income regions drop) and/or workers migrate (Drewes, 1986; Frantantoni and

Schuh, 2003). Moreover, fiscal efforts to diversify regional economies, like those undertaken by the Canadian government’s Western Economic

Diversification programme, should produce increasingly homogenous rate-sensitivity across regions over time, making monetary policy all the more powerful a macroeconomic tool.

This is not to say that monetary authorities are unaware of subnational variation. Indeed, Eddie

George, former Governor of the Bank of

England, famously admitted that he judged unemployment in the north ‘an acceptable price to pay for the control of inflation’ (Coyle, 1998).

Confronted with regional dissent, many central banks have built regional representation into their institutional structure. The Board of

Governors of the Fed has some rotating regional membership, drawn from its 12 regional reserve banks, and the Bank of Canada has an informal tradition of provincial representation on the

Board of Directors. In both cases, core regions are still privileged – the New York Fed, with its tight links to Wall Street, is the only regional bank with a permanent place on the Board of

Governors, and Ontario and Que´bec each have twice the membership of any other province on the Board of Directors – but regional representation is not entirely absent.

From a geographical and distributional perspective, however, significant unevenness persists because of the virtually complete capture of central bank control and monetary policy decision-making by one class fraction, finance capital. With very few exceptions, regardless of region, central bankers come to monetary policy work from the financial sector, and when they do not, they come from affiliated fields

(university economics departments or the IMF, for example). In Canada, the directors have a somewhat broader background, but have basically no influence on policy, which is determined by the Governor and his council (Clark,

1996: 335). The justification for this narrow range of occupational and class backgrounds among monetary policy-makers is the expertise

14

Mann 15 necessary for the job, but that does nothing to address the fact that monetary authority throughout the global North is in the hands of a group of men – they are virtually all men – who share a perspective and privilege. Studies of policy voting behaviour show conclusively that who central bankers are – where they come from, their gender and class background, their politics, training, occupational histories, etc – is relevant to any understanding of their policy stance (Greider,

1987; Gildea, 1990; Havrilesky and Schweitzer,

1990; Bernhard et al ., 2002: 713–19). The political economic import of these particulars presumably only increases in proportion to the degree of autonomy the central bank enjoys (Friedman and

Schwartz, 1963: 419; Siklos, 1999).

In fact, one of the most influential models of monetary governance recommends the appointment of a ‘conservative central banker’ whose

‘inflation-aversion’ is greater than that of society as a whole (Rogoff, 1985). Inflation-aversion is highest among creditors (Epstein, 1992; Posen,

1995: 257; Bearce, 2003: 400), and significantly higher among the rich than the poor across many otherwise very different parts of the world

(Jayadev, 2006), since the principal opposition to inflation (and thus the support for IT rules) is due to the fact that unanticipated inflation redistributes income from finance capital and the wealthy to lower-income groups and debtors

(Hetzel, 1990: 99; Panico and Rizza, 2004: 454;

Meh and Terajima, 2008). This is to say that the

Rogoff model essentially asserts that central bankers must be creditors – ie, they must represent finance capital.

Finance capital’s increasing control of central banks is, as such, a priori for both the theory and practice of modern monetary policy. Empirical studies confirm this. Adam Posen’s (1995) influential work on ‘financial opposition to inflation’ shows clearly that the degree of central bank independence (see section II(2) above), ‘reflects national differences in effective financial opposition to inflation’ (Posen, 1995: 271):

The financial sector gains access to elected government and central bank officials by being their main external sources of information and advice on monetary policy . . .

[T]he financial sector’s monitoring of the central bank’s actions and top personnel plays the most prominent role in the government’s evaluation of central bank policy. (Posen, 1995: 227)

Monetary authorities can depend upon finance capital to defend contemporary central banking practice. ‘The Fed identifies its self-interest with the self-interest of groups antipathetic to the redistribution of income associated with unanticipated inflation. It can then appeal to these groups when its institutional autonomy is threatened’ (Hetzel, 1990: 102). While the recent crisis has troubled the relation between global finance capital and central banks, especially regarding the expansion of their regulatory authority (Guha and Braithwaite, 2009), a shared commitment to strong institutional independence persists (Gertler, 2009).

The class politics at work is not specific to the post-Fordist, neoliberal era. Monetary policy was an effective tool of capital before Volcker.

Dickens (1995), for example, shows how the Fed used tighter monetary policy in the late 1950s to suppress insurgent labour in core industries.

Arrighi argues that Nixon, confronting historically unprecedented working-class power, adopted an ‘inflationary form of crisis management’ for the downturn that began in the late

1960s (in contrast to the deflationary form it took in the late nineteenth century and during the

Depression):

To put it bluntly, at the end of the long postwar boom, the leverage of labour in core regions was sufficient to make any attempt to roll it back through a serious price deflation far too risky in social and political terms. An inflationary strategy, in contrast, promised to outflank workers’ power far more effectively than international factor mobility could.

(Arrighi, 2007: 130)

From this perspective, the breakdown of the labour-capital accord that characterized Fordism

15

16 Progress in Human Geography is the result of capital’s realization of the long-run futility of Nixon’s mode of crisis management (Ingham, 2004: 148), a movement that reached its crescendo with the imposition of global financial hardship by Volcker’s Fed beginning in 1979 (ie, before Reagan). Not incidentally, it also marks the point at which the influence of the financial sector on monetary policy increased considerably, while that of non-financial interests declined, at least in the

USA, Canada, and parts of western Europe

(Panico and Rizza, 2004; Weise, 2008).

It is notable, too, that it is not only critics of orthodox economic policy-making who emphasize these class dynamics. Mainstream economists give similar credence to the utility of monetary policy in managing working-class demands, although they tend to share the perspective of the victors in the antagonisms of recent years. As

Charles Freedman, a long-time Bank of Canada economist and deputy governor, put it in a celebration of IT:

[M]any of the other benefits anticipated from low inflation, such as low and less variable interest rates, longer terms of wage settlements, fewer costof-living adjustment (COLA) clauses, a reduction in the number of workdays lost to strikes, a lengthening in the terms of financial contracts, and well-anchored inflation expectations, have also been realized. (Freedman, 2005: 186)

Since, in the IT era in Canada, real wages have fallen, and income and wealth inequality has accelerated, labour’s quiescence is presumably not due to growing satisfaction with macroeconomic conditions, monetary policy, or labour relations. Since the decrease in COLAs and strikes is clearly associated with a general decline in the power of unions in Canadian labour markets, there is no other way to read

Freedman’s claim than as a clear endorsement of Canadian monetary policy’s contribution to the suppression of labour. Indeed, that is exactly what it is. Whether or not democracy has an

‘inflationary bias’, in anything like a reasonably democratic nation finance capital’s effort to constrain the state from following an ‘unduly’ inflationary path depends absolutely on crushing workers’ opposition. That effort is abetted by an ideology of shared interests between capital and labour, according to which inflation is an unambiguous cost (Ingham, 2004: 149). Since inflation has long been attributed to workers’ wage demands like COLAs (cf. Rudd and Whelan, 2005; Mitchell and Erickson, 2008), ending it is predicated on workers’ silence. In this light, the Bank of Canada’s serious consideration of price-level path targeting (Bank of Canada,

2008: 17), an anti-inflationary policy rule more radical than IT, is an indication of how completely labour has lost its voice in macroeconomic management.

15

The hegemony enabled by these relations shapes the distributive effects of monetary policy significantly. Most notably, it has a negative impact on wages (Arestis et al ., 2006) and employment levels. Analyses in several nations demonstrate that inflation-oriented, independent central banks depress employment levels over time, undermining hegemonic macrotheories that assume ‘monetary neutrality’ – ie, monetary policy has no effect on real variables beyond the immediate term (Fortin, 1996; Iversen, 1998;

Cornwall and Cornwall, 1998; Palley, 2006;

Epstein, 2008). These effects may be exacerbated by regional disparities (Dow and Montagnoli, 2007; Jackson, 1998). The specific spatial implications of this distributional regime at several scales are undoubtedly enormous, and merit the kind of detailed analysis Hamnett

(1997) performed on Thatcher’s tax cuts.

IV Conclusion: spatial ideologies of monetary policy

To conclude, I will draw out three geographical arguments from my analysis. The first concerns the performativity of central banking for the spatial economy. Many of the claims regarding the power of monetary policy are the outcome of

16

Mann 17 ongoing processes of real abstraction under capital, and are themselves materially and ideologically productive – ie, performative. As

Ingham (2004) explains:

What are twenty-first century central banks doing?

Manifestly, they are attempting to establish a transparent procedural correctness that is assessed according to the agreed organizational arrangements and the current macro-economic thinking.

The construction of the institutional fact of stable money is established, in part, by the performativity of economic theory and practice conducted by experts . . .

Performativity is seen very clearly in the efficacy attributed to inflation targeting – that is to say, the belief that the mere setting of a target will bring about the intended result. (Ingham, 2004:

148)

For Ingham, a Weberian, the ultimate aim of central banks and their monetary policies is ‘the highest level of formal rationality of inflation expectations’ (2004: 149) in the interests of a hierarchically stable institutional rationality shared by the state, its constituents, and the markets.

Ingham’s comments bring me to my second concluding point, which concerns monetary policy and state territorialization. For an emphasis on institutional rationality can serve, at the scale of the state, as a complement to Harvey’s account of capitalism’s ‘creation of nested hierarchical structures of organization’ – in effect, the production of scale – in the attempt to confront, at a global level, the ‘tensions between fixity and motion in the circulation of capital’ (Harvey,

1999: 422; cf. Leyshon and Thrift, 1997: 49–

50). In Brenner’s (1998: 461) compelling elaboration of these ideas, the state as a specific form of territorial organization is a crucial aspect of the ‘scalar fix’ for capital.

That scalar fix has multiple material and ideological modes through which it is configured, and, as Leyshon and Thrift (1997: 260–321) show brilliantly, money is among them. Since the literature analysing these modes has a decidedly international or global leaning, much attention has been paid to international currency regimes like Bretton Woods and the more informal US dollar hegemony constituted since its collapse (Swyngedouw, 1997; Arrighi, 2007).

But it is also true that the intraterritorial circulation of national money – defined as such by virtue of its denomination by the state as the domestic unit of account (Keynes, 1976;

Aglietta, 2002; Ingham, 2004) – is among the most essential modes in the production of the state as scalar fix (Helleiner, 1999; Gilbert,

2006). In fact, although it may be a stretch to assert that the space of domestic monetary circulation defines state territory, not vice versa , it is nevertheless the case that the coherence of that territory, and the relations it ‘contains’, are tightly bound to the value and stability of domestic money (Cohen, 1998). To talk of the end of money is surely to talk of the end of the state

(Mann, 2008).

There is much excellent work by geographers and other social scientists on the work that money does in this regard (eg, Dodd, 1994;

Leyshon and Thrift, 1997: 291–321; Bryan and

Rafferty, 2007), but little consideration of the necessary and commensurate work of monetary policy and its institutional infrastructure. Yet surely, if the modern state lives on (in many ways robustly) when it was supposed to have withered in the face of international capital, it lives through its money. The management of the current crisis and the recent domination of monetary policy in the macroeconomic mix index the extent to which many states identify their interests as coextensive with those monetary relations. The domestic regulation of money is essential to the production and reproduction of the state. This works in the material ways described above, through which central banks rewrite subnational economic geographies by disciplining intranational difference, but it also works ideologically through the production of a class-differentiated political economic citizenship sufficiently loyal to an aggregate ‘national’ welfare to accept that discipline as necessary.

17

18 Progress in Human Geography

These questions bring me to my third conclusion, on the political geography of financial regulation in the IT era. In contemporary capitalist states, the very structure of modern monetary authority has a distinctively Hobbesian quality.

Technocratic, class-privileged, autonomous governance of central material and ideological aspects of collective and individual life – ie, money and monetary relations – is difficult to reconcile with any acceptable definition of democracy, but it is nevertheless modern monetary policy’s modus operandi : to paraphrase

Hobbes himself, Autoritas, non veritas, facit pecuniam .

16

Complete and unchallengeable control of the monetary regime is in fact the standard against which ‘new consensus’ economists and central bankers measure the ‘inefficiency’ of current practice. For ‘efficient’ monetary policy,

‘one must either permit an initial government to make decisions binding for all time . . .

or restrict available strategies [of future governments] still further’, thereby effecting the same outcome: the goal is a situation in which one either sets policy now for all time, or makes it impossible for anyone to change policy in the future (Lucas, 1986: 128). Framed in these terms, conversations inside the central banking community consequently substitute ‘credible’,

‘transparent’, and ‘accountable’ for ‘democratic’ (eg, Woodford, 2003: 2–17), despite the fact that the first two bear absolutely no necessary relation to democracy, and the last, instantiated in the goal dependence-instrument independence arrangement, in practice merely describes the central bank’s relation with those who share its expertise. The IT regime in Canada has been renewed four times since 1991, and only economists and capital participate in the discussions.

In sum, modern monetary policy is deemed unsuitable for democratic deliberation, and intentionally operates out of public reach. Here,

‘democracy’ is merely an information problem, a principal-agent relation in which the ‘asymmetry’ – central bankers’ privileged knowledge and autonomous authority – is not to be overcome, but preserved and made permanent. As one of the world’s most influential monetary economists puts it, ‘what is important is not so much that the central bank’s deliberations themselves be public, as that the bank give clear signals about what the public should expect it to do in the future’ (Woodford, 2003: 17).

Do people ‘need to be fooled’ (Drazen, 2000:

109) by central banks? Do they need monetary governance more ‘conservative’ than themselves (Rogoff, 1985)? That much of the orthodox theory of monetary policy answers these questions affirmatively is telling, but, like its reasons – inflation bias, time-inconsistency, the

‘hurly-burly’ of politics – it dodges many of the most important problems. Surely now is the time to formulate questions adequate to the dynamic complexity of the political economy and geography of the contradictory amalgam that constitutes ‘actually existing neoliberalism’

(Brenner and Theodore, 2002; Peck, 2004). But what alternative approaches might be available?

If money is not the one sphere in which we should accede to the Leviathan, then what is to be done? Mandate rotating elected representatives on central bank policy committees? Allow referenda on policy rules? Grant regional and/or sectoral vetoes? Have fiscal agents reabsorb monetary authority? Abolish monetary policy in favour of Hayek’s (1976) market in private monies, in which the most ‘competitive currencies’ win? All that can be said at this point is that there are more options open to us than the hegemonic narrative of monetary stability and central bank independence at all costs would have us believe, and that the right questions – questions that reinvigorate the politics so ironically subdued by the term ‘policy’ – are crucial. And some of the possibilities available might be initially identified by a critical public discussion of the stakes in monetary governance. In other words, what if our first questions were not what can monetary policy do, and how does it do it – these lead almost inevitably to a technical

18

Mann 19 discussion open to the expert or powerful few – but politically prior and more fundamental questions: what should monetary policy do, and why?

Acknowledgements

Thanks very much to Roger Lee, Joel Wainwright,

Peter Mann, and those reviewers who remain anonymous. This research was supported by the Social

Sciences and Humanities Research Council of

Canada (grant number 410-2009-2812).

Notes

1. Jones (1984), Leyshon and Thrift (1997), and Martin

(2001) contain more limited or indirect discussions.

2. Innovative quantitative approaches may also get at some of the crucial dynamics.

3. See, for example, the recent debate on the Fed’s ‘dual mandate’ in the journal International Finance (Friedman, 2008; Schwartz and Todd, 2008).

4. For precisely the reasons enumerated above regarding the limits of the federal funds rate, in the implementation of

US monetary policy much depends on the Fed’s OMOs.

5. The ‘term structure of interest rates’ is a ‘curve’ because yields on bonds vary by time to maturity. Usually, it is positively curved and mostly monotonic (meaning its upward direction is not interrupted by downward blips), because a bond’s yield is normally higher the longer its term to maturity, longer terms implying increased risk and opportunity cost. Throughout the autumn of 2008, however, parts of the yield curve were ‘inverted’, since the short term seemed unstable relative to the recovery expected in the medium to longer run. The Fed regards the yield curve as a crucial ‘leading indicator’. For a graphic illustration for the Euro area, see http://www.ecb.int/stats/money/yc/html/index.en.html (last accessed

28 October 2009).

6. The inflation-unemployment relationship is described by the famous Phillips curve, the long-term and shortterm shapes of which have been a topic of much debate in macroeconomics since Phillips’ original 1958 paper.

7. There are good reasons to challenge this consensus.

More on this below, but see Cornwall and Cornwall

(1998) and Desai et al . (2003).

8. The independence conditions of the US Federal

Reserve are up for debate. Baltensperger et al . (2007:

97) classify it as goal independent under Greenspan, but current Chair Bernanke has advocated goal dependence in his published work (Bernanke et al ., 1999). In other parts of the world, institutional arrangements are more varied. Chinese monetary policy, for example, is formulated by the People’s Bank of China but approved by the State Council. Governor Zhou Xiaochuan and his deputies cannot develop policy unpalatable to fiscal-political authorities: ‘PBoC proposes but the

State Council disposes’ (He and Pauwels, 2008: 4–5;

Laurens and Maino, 2007: 19).

9. Extreme, and increasingly uncommon, ways of targeting real exchange rates used in the past include fixed exchange rates (during and after the Bretton Woods era), and ‘dollarization’, the adoption of another country’s currency. Exchange rate targeting like that practised in

Argentina aims at a non-fixed, but ‘stable and competitive’ real exchange rate, which allows monetary policy a great deal more room for manoeuvre than the country’s former peg to the US dollar (Frenkel and Rapetti, 2008).

In an era of capital mobility and global currency markets, fixed exchange rates, as Sweden learned in the early

1990s, are easy to speculate against and hard for monetary authorities to defend (Obstfeld and Rogoff, 1995).

10. IT banks that focus on the CPI are usually interested in

‘core’ as opposed to ‘headline’ inflation (Hogan,

2000). Core CPI measures movement in the prices of the CPI’s basket of goods, but excludes its more volatile components like fruit, vegetables, and fuel.

Despite its attraction to central bankers, who worry only if headline inflation ‘spills over’ into the core, many argue that core CPI is enormously problematic

(Laidler and Aba, 2000; Arestis et al ., 2006; Laidler and Banerjee, 2008), since it would seem to measure

‘inflation excluding inflation’, in blogger Barry

Ritholtz’s apt phrasing (http://www.ritholtz.com; last accessed 28 October 2009). While neither the Fed nor the Bank of England use the CPI, both nonetheless rely on ‘core’ versions of their respective measures of inflation (Laidler and Banerjee, 2008).

11. The same can be said of the Bank of Japan, the Swiss

National Bank (Baltensperger et al ., 2007: 90–95), even the People’s Bank of China (He and Pauwels,

2008: 26), all of which are implicit IT banks, the last in perhaps a less transparent manner.

12. Government revenues are positively affected by low inflation since many taxes and transfers are only partially indexed, or even non-indexed to inflation. Any transfer payment not fully indexed costs the government less in real dollars over time, and any taxes that

19