A VOLUME-BASED METHOD FOR DENOISING ON CURVED SURFACES Harry Biddle

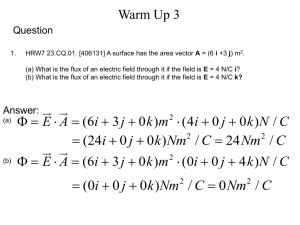

advertisement

A VOLUME-BASED METHOD FOR DENOISING ON CURVED SURFACES Harry Biddle Ingrid von Glehn, Colin B. Macdonald, Thomas März∗ Double Negative Visual Effects London, UK Mathematical Institute University of Oxford Oxford, UK vonglehn|macdonald|maerz@maths.ox.ac.uk hb@dneg.com ABSTRACT We demonstrate a method for removing noise from images or other data on curved surfaces. Our approach relies on in-surface diffusion: we formulate both the Gaussian diffusion and Perona–Malik edge-preserving diffusion equations in a surface-intrinsic way. Using the Closest Point Method, a recent technique for solving partial differential equations (PDEs) on general surfaces, we obtain a very simple algorithm where we merely alternate a time step of the usual Gaussian diffusion (and similarly Perona–Malik) in a small 3D volume containing the surface with an interpolation step. The method uses a closest point function to represent the underlying surface and can treat very general surfaces. Experimental results include image filtering on smooth surfaces, open surfaces, and general triangulated surfaces. Index Terms— Image denoising, Surfaces, Partial differential equations, Numerical analysis. 1. INTRODUCTION Denoising is an important tool in image processing and often forms a crucial step in image acquisition and image analysis. On general curved surfaces, denoising and the corresponding scale space analysis of images, as well as other image processing tasks have seen some interest [1]. For example, Kimmel [2] studies an intrinsic scale space for images on parametrically-defined surfaces via the geodesic curvature flow. More recently, Spira and Kimmel [3] use the same flow for segmentation of images painted on parametrically-defined manifolds. Bogdanova et al. [4] perform scale space analysis as well as segmentation for omnidirectional images defined on various shapes. Our aim here is to provide simple numerical realizations of the Gaussian diffusion filter and the nonlinear Perona–Malik [5, 6, 7] edgepreserving diffusion filter for images on general surfaces. Fig. 1 shows an example comparing the two approaches. In applications, image processing on curved surfaces can occur even when data is acquired in three-dimensional volumes. For example, Lin and Seales [8] propose CT scanning of scrolls in order to non-destructively read text written on rolled up documents. In digital image-based elasto-tomography (DIET), a new methodology for non-invasive breast cancer screening, the surface and the surface data are measured from strobed lighting with several calibrated digital cameras [9]. In such applications, it may be useful to perform denoising and other techniques on surfaces embedded in three-dimensional volumes. Denoising on surfaces is also related to ∗ The work of all authors was partially supported by Award No KUKC1-013-04 made by King Abdullah University of Science and Technology (KAUST). (a) (b) (c) Fig. 1. Denoising on the surface of a fish using our algorithm. The original noisy surface data is shown in (a), Gaussian diffusion gives (b) with blurry edges whereas (c) shows that Perona–Malik diffusion removes the noise while maintaining sharp edges. surface fairing if the surface data is a height-field which gives a perturbed surface of interest as a function on a reference surface [10]. In this context the Perona-Malik model and variations of it have already been considered in the literature [10, 11, 12]. A common theme in many techniques (e.g., [2, 3, 4] above) is the use of models based on partial differential equations (PDEs). Applying PDE-based models on surfaces requires some representation of the geometry and this choice is significant in the complexity of the resulting algorithm. A common choice is a parameterization of the surface; however this introduces artificial distortions and singularities into the model, even for the simplest surfaces such as spheres. On more complex geometry, joining up small patches is typically required. On a triangulated surface, PDEs can be discretized using finite element methods, e.g., [13]. Alternatively, implicit representations such as level sets (e.g., [14]) or the closest point representation employed here can be used. These tend to be flexible with respect to the geometry although level sets do not give an obvious way to treat open surfaces. Using level set methods in a 3D neighbourhood of the surface also requires introducing artificial boundary conditions at the boundary of the computational band. In this work we use the Closest Point Method [15] for solving both the Gaussian and Perona–Malik diffusion models on surfaces. Using this technique, we keep the resulting evolution as simple as possible by alternating between two straightforward steps: 1. A time step of the model in three dimensions using entirely standard finite difference methods. 2. An interpolation step, which encodes surface geometry and makes the 3D calculation consistent with the surface problem. One benefit is that the Closest Point Method uses a closest point function [15, 16] to represent the surface, and therefore does not require modification of the model via a parameterization nor does (a) (b) (c) Using this representation, we can extend values of a surface function u into the surrounding volume by defining v : R3 → R by v(x) := u(cp(x)). (2) Fig. 2. Our computational technique, illustrated here in two dimensions, is based on a volume representation of a surface (a) where each grid point (voxel) knows the closest point on the surface. On a uniform grid of points surrounding the surface, we then alternate between two steps: (b) evolving the Perona–Malik equation using a finite difference stencil at each grid point; and (c) replacing the value at each grid point with the value at its closest point, using bi-cubic interpolation. it require the surface to be closed or orientable. The Closest Point Method has already been used successfully in PDE-based image segmentation [17] and PDE-based visual effects [18]. In §2, we demonstrate the Closest Point Method by applying it to the standard diffusion equation. This gives a method for Gaussian filtering on surfaces. §3 reviews the Perona–Malik model for edge-preserving diffusion and adapts it to the Closest Point Method. This is followed by numerical experiments in §4. 2. SOLVING DIFFERENTIAL EQUATIONS ON SURFACES We begin by demonstrating our approach on the Gaussian diffusion equation using the Closest Point Method [15]. This flow does indeed remove noise from the image but it also results in considerable blurring of edges. In order to preserve edges we extend the approach to the nonlinear Perona–Malik model in §3. The technique presented here is more general than either equation and can be applied to a wide variety of surface differential equations. 2.1. Surface functions and images Suppose we have a surface function u0 : S → R which takes each point on the surface S and returns a real number. We will think of this function as representing image data on the surface where the values of u0 encode intensity (for colour images, we could replace u0 with a vector function u0 : S → R3 ). We can blur such a surface image by solving the surface PDE ∂u = ∆S u, ∂t (1) for a finite time from initial conditions consisting of our image u0 . Here ∆S is the Laplace–Beltrami operator, the surface intrinsic analogue of the Laplacian diffusion operator. We solve (1) by embedding the surface in a higher dimensional space (typically a threedimensional volume). 2.2. Representing the surface We represent the surface S using a closest point representation: each point x ∈ R3 is associated with its geometrically closest point on the surface cp(x) ∈ S. Fig. 2a shows a closest point representation of a curve (an example of a one-dimensional surface embedded in two dimensions). Notably, v will be constant in the direction normal to the surface. This feature is crucial because it implies that an application of a Cartesian differential operator (such as the gradient or Laplacian) to v is equivalent to applying the corresponding intrinsic surface differential operator to u. These mathematical principles are established in [15, 16]. 2.3. The Closest Point Method We want to solve the three-dimensional diffusion equation ∂v = ∂t ∆v subject to the constraint that v(x) = v(cp(x)) (i.e., that v remains constant in the normal direction). One simple approach to solving this constrained problem is to discretize in time and alternate between advancing the three-dimensional PDE in time and reextending the results [15]. Using the forward Euler time-stepping algorithm with step size τ , this gives the following two-step process n n n ṽ n+1 := v n + τ ∆v n = v n + τ vxx + vyy + vzz , (3a) v n+1 := ṽ n+1 (cp(x)). (3b) Note that the temporary ṽ n+1 contains the result of a forward Euler step using the Cartesian Laplacian, but this might not be constant in the normal direction, so we re-extend to obtain v n+1 . For additional accuracy, this can easily be extended to higherorder Runge–Kutta or multistep methods [15]. Implicit methods are also practical [19, 20] and useful if the problem is stiff. 2.4. The role of voxels We discretize the three-dimensional embedding volume, typically with a uniform Cartesian grid as this makes the algorithm straightforward to implement and analyze. We will think of this threedimensional voxel grid as our discrete image with the voxel size parameter h specifying scale. This could be appropriate if the surface and image data were acquired in three dimensions using e.g., CT scans [8]. In that case, the grid parameter h could be naturally chosen by the resolution of the CT machine. In other cases, h may simply be a numerical parameter. Acquiring closest point representations is a research area in its infancy and for now we assume such a representation is given. However, it is straightforward to convert triangulations into this formation [21] or to perform steepest descent on level-set representations [16]. 2.5. Interpolation Because we are working on a discrete grid, cp(x) is likely not a grid point and thus we need a way to approximate the extension operation of (3b). One approach is to use interpolation on a stencil consisting of the surrounding grid points nearby cp(x) [15]. We use a standard tri-cubic interpolant which gives good accuracy and stability; a schematic of the extension is shown in Fig. 2c. The numerical properties of the Closest Point Method are fairly well-understood [15, 16, 19, 20, 22] and highly accurate computations have been done up to fifth-order accuracy [21]. In some cases, stability analysis has also been performed [22, 23]. The operations can also be accelerated using a multigrid strategy [23] although we do not do so here. 2.6. Banding We have described the algorithm as taking place on the voxel grid of a full cube. This will work fine in practice but many of the grid points are not required and thus the code can be made more efficient by working on a narrow band of points surrounding the surface. For any particular discretization, the minimum bandwidth is easily computed as a small multiple of h and using a wider band will have no effect on the solution. Notably, no artificial boundary condition need be imposed at the edges of the band [15]. 3. PERONA–MALIK DENOISING The Perona–Malik equation [5, 6] is a classic modification of Gaussian diffusion that employs edge preservation by varying the diffusion coefficient across the image, penalising it at edges and structures that should be preserved in the image. The equation in its general form is ∂u (4) = div g(|∇u|) ∇u , ∂t where the image is defined on a finite rectangle Ω ⊂ R2 via a function u : R2 7→ R that describes the pixel intensity at any given point, for example where one is white and zero is black. If the diffusion coefficient g : R → R is taken to be a constant, we recover the Gaussian diffusion equation. Instead, we take the popular choice g(s) = 1 1+ s2 λ2 . (5) Edges are detected via the gradient: a large gradient |∇u| λ means that we are close to an edge and the diffusion almost stops, since g ≈ 0. A small gradient |∇u| λ means that we are away from edges, hence we filter (locally) with Gaussian diffusion, since g ≈ 1. Here λ is a tunable parameter that controls the sensitivity of the scheme to visual edges; it gives a threshold to separate noise from edges. 3.1. Perona–Malik on surfaces To formulate Perona–Malik diffusion on a surface S, we simply replace operators with in-surface operators: ∂u = divS g(|∇S u|) ∇S u . ∂t (6) The original noisy surface image is the initial condition u0 : S → R. We solve this equation for t ∈ [0, tfinal ], where the final time is a second parameter which controls the amount of denoising. 3.2. Numerical discretization We start with the three-dimensional Cartesian form of (4) i ∂ h q 2 ∂v = g vx + vy2 + vz2 vx + ∂t ∂x i i ∂ h ∂ h g(. . .) vy + g(. . .) vz , ∂y ∂z and discretize with a textbook-standard finite difference scheme for parabolic equations. Combined with forward Euler, the time- evolution in 3D is thus given by n x n n x n gi+1/2,j,k D+ vijk − gi− 1/2,j,k D− vijk n+1 n ṽijk = vijk +τ + h y n y n n n gi,j+ 1/2,k D+ vijk − gi,j−1/2,k D− vijk + h n z n n z n gi,j,k+1/2 D+ vijk − gi,j,k−1/2 D− vijk . (7a) h α α Here D+ and D− indicate forward and backward finite differences, in the direction indicated by the superscript α, on a grid spacing of h. The expressions involving g between grid points are calculated as the average of the values at the two neighbouring grid points, e.g., n n n 1 gi+ 1/2,j,k = 2 (gi+1,j,k + gijk ), n n n 1 gi− 1/2,j,k = 2 (gi−1,j,k + gijk ), (7b) n where the nodal gijk are computed using central finite differences α Dc applied to g(|∇u|) q n n n n gijk =g (Dcx vijk )2 + (Dcy vijk )2 + (Dcz vijk )2 . (7c) As in (3), after advancing the solution in time using the above scheme, we perform a re-extension of the surface values n+1 = ṽ n+1 (cp(xijk )), vijk (8) where ṽ n+1 (cp(xijk )) is approximated with tri-cubic interpolation on the surrounding grid points (see Fig. 2c). The numerical scheme (7) uses a stencil shown in Fig. 2b. The extension (8) uses the tri-cubic interpolation stencil shown in Fig. 2c. To determine the minimal computational band §2.6, we must be able to apply former stencil at each point in the latter [15]. In 3D, this results in a band with a width of 4.9h. We note that the computational band scales with the area of the surface and not with the volume of the embedding space. In practical computations, we find this band contains less than 10% of the (theoretical) voxels of the bounding box of the surface (and the difference is even more significant in highly-resolved calculations). For a chosen number of time-steps, the running time scales linearly with the number of voxels in the computational band. 4. RESULTS The results of our algorithm are demonstrated in Fig. 1, which shows denoising on the surface of a triangulated fish [24]. Gaussian diffusion blurs the image, while Perona–Malik diffusion removes noise while preserving sharp edges. Our implementation uses M ATLAB. Parameters used were h = 0.002, λ = 5, and 100 time steps of size τ = 0.15h2 = 6 × 10−7 . The fish is about 1 unit long. The computational band consists of 2 837 600 voxels surrounding the fish. Each of the 100 time-steps takes about 1 second on an Intel Core i7 CPU running at 3.20 GHz. Our surface images have a range of [0, 1]. In our experiments, we apply additive noise in the embedding volume, normally distributed with amplitude 0.3, mean 0 and standard deviation 1. However, Perona–Malik is not limited to this noise model. Fig. 3 shows an example of computing on the surface of a globe. In Fig. 3c we show that our approach results in a uniform application of denoising over the surface. We also demonstrate that if one first maps the surface image data onto a plane (easy enough here with a sphere but quite hard in general), and naively applies the standard (a) (b) (c) Fig. 3. Denoising on a unit globe. (a) Original noisy surface data. In (b) the data was projected to a 2D image where Perona–Malik denoising was performed. We note artifacts near the pole, while (c) shows Perona–Malik diffusion on the surface using our approach gives a uniform treatment all over the surface. We use h = 0.01, λ = 5 and 100 time steps of size τ = 1.5×10−5 . The computational band consists of 1 232 586 voxels surrounding the surface. Each time step takes about 0.4 seconds. (a) (b) Fig. 5. Perona–Malik denoising of an image texture-mapped onto an open fishbowl of unit radius. (a) Noise added in the embedding volume. (b) Denoised image, using h = 0.007, λ = 5, and 109 time steps of τ ≈ 7.34 × 10−6 . The computational band consists of 1 927 978 voxels and each time step takes about 0.6 seconds. (Photograph by the first author.) 1.2 total average area 1 area 2 area 3 average intensity 1 0.8 0.6 0.4 0.2 0 −0.2 0 20 40 60 timesteps 80 100 Fig. 4. The average grey level over the image is preserved using Perona–Malik denoising. The average grey level over the small regions shown is also preserved. planar Perona–Malik, distortions from the parameterization appear in the image. In particular, if the noise is added in the 3D embedded volume, then projection onto a 2D plane can easily distort the noise so much as to make denoising with the (standard) planar Perona–Malik impractical (see Fig. 3b). Although this approach can be ameliorated by a significant modification of the PDE (involving the metric tensor and artificial boundary conditions), this must be done for each surface. This contrasts with our approach where the standard 3D Perona–Malik PDE is applied independent of the specific geometry. The average intensity of the entire surface image should be constant (as can be seen from the divergence theorem on (6)). Fig. 4 shows this is the case using our algorithm. Additionally, in cartoonlike images, we can expect the average intensity in certain smaller subregions to be invariant. Fig. 4 also shows this form of contrast preservation. Fig. 5 shows another example where an image has been texture mapped onto a curved surface. The denoising algorithm is performed in the embedding volume. The surface in this case is open, which is easily handled by our algorithm—a homogeneous Neumann condition is automatically applied by the re-extension [15]. 5. SUMMARY AND CONCLUSIONS In this paper, we describe a numerical realization of nonlinear diffusion filters for images on general surfaces. We obtain our filters by combining the in-surface PDE models of Gaussian or Perona–Malik edge-preserving diffusion with the Closest Point Method. The re- sulting filter is simple: it alternates a time step of the corresponding diffusion PDE in a 3D volume surrounding the surface with a reextension step. In this approach we use the closest point function to represent the surface. Notably, only the re-extension step evaluates the closest point function, and the PDE need not be transformed as in other approaches to surface PDEs. The fully discrete algorithm uses standard finite difference techniques on a voxel grid to approximate the diffusion operators and tri-cubic interpolation to do the re-extension. Our experiments demonstrate that the filter works well and that we can handle complex geometries. Here we have considered Gaussian and Perona–Malik diffusion on surfaces but the Closest Point Method is not limited to these two models. Indeed, the Closest Point Method applies generally to surface PDEs and could be useful in other surface image processing tasks. Applications other than denoising include deblurring and inpainting and are part of ongoing research. 6. REFERENCES [1] R.-J. Lai and T.F. Chan, “A framework for intrinsic image processing on surfaces,” Comput. Vis. Image Und., vol. 115, no. 12, pp. 1647–1661, 2011. [2] R. Kimmel, “Intrinsic scale space for images on surfaces: The geodesic curvature flow,” in Graphical Models and Image Processing. 1997, Springer-Verlag. [3] A. Spira and R. Kimmel, “Geometric curve flows on parametric manifolds,” J. Comput. Phys., vol. 223, 2007. [4] I. Bogdanova, X. Bresson, J.-P. Thiran, and P. Vandergheynst, “Scale-space analysis and active contours for omnidirectional images,” IEEE Trans. Image Process., vol. 16, no. 7, 2007. [5] P. Perona and J. Malik, “Scale-space and edge detection using anisotropic diffusion,” in Proceedings of IEEE Computer Society Workshop on Computer Vision, 1987. [6] P. Perona and J. Malik, “Scale-space and edge detection using anisotropic diffusion,” IEEE Trans. on Pattern Analysis and Machine Intelligence, vol. 12, 1990. [7] J. Weickert, Anisotropic Diffusion in Image Processing, B.G. Teubner Stuttgart, 1998. [8] Y. Lin and W.B. Seales, “Opaque document imaging: Building images of inaccessible texts,” in Proc. ICCV’05, 10th IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision vol. 1, 2005. [9] R.G. Brown, C.E. Hann, and J.G. Chase, “Vision-based 3D surface motion capture for the DIET breast cancer screening system,” Int. J. Comput. Appl. T., vol. 39, no. 1, pp. 72–78, 2010. [10] M. Desbrun, M. Meyer, P. Schröder, and A.H. Barr, “Anisotropic feature-preserving denoising of height fields and bivariate data,” in Graphics Interface, 2000, pp. 145–152. [11] U. Clarenz, U. Diewald, and M. Rumpf, “Processing textured surfaces via anisotropic geometric diffusion,” IEEE Trans. Image Process., vol. 13, no. 2, pp. 248–261, 2004. [12] C.L. Bajaj and G. Xu, “Anisotropic diffusion of surfaces and functions on surfaces,” ACM Trans. Graphic., vol. 22, no. 1, pp. 4–32, 2003. [13] G. Dziuk and C.M. Elliott, “Surface finite elements for parabolic equations,” J. Comp. Math., vol. 25, no. 4, 2007. [14] M. Bertalmı̀o, L.-T. Cheng, S. Osher, and G. Sapiro, “Variational problems and partial differential equations on implicit surfaces,” J. Comp. Phys., vol. 174, no. 2, 2001. [15] S.J. Ruuth and B. Merriman, “A simple embedding method for solving partial differential equations on surfaces,” J. Comput. Phys., vol. 227, no. 3, 2008. [16] T. März and C.B. Macdonald, “Calculus on surfaces with general closest point functions,” SIAM J. Numer. Anal., vol. 50, no. 6, 2012. [17] L. Tian, C.B. Macdonald, and S.J. Ruuth, “Segmentation on surfaces with the Closest Point Method,” in Proc. ICIP09, 16th IEEE International Conference on Image Processing, 2009. [18] S. Auer, C.B. Macdonald, M. Treib, J. Schneider, and R. Westermann, “Real-time fluid effects on surfaces using the Closest Point Method,” Comput. Graph. Forum, vol. 31, no. 6, 2012. [19] C.B. Macdonald and S.J. Ruuth, “The implicit Closest Point Method for the numerical solution of partial differential equations on surfaces,” SIAM J. Sci. Comput., vol. 31, no. 6, 2009. [20] I. von Glehn, T. März, and C.B. Macdonald, “An embedded method-of-lines approach to solving PDEs on surfaces,” submitted, 2013. [21] C.B. Macdonald and S.J. Ruuth, “Level set equations on surfaces via the Closest Point Method,” J. Sci. Comput., vol. 35, no. 2–3, 2008. [22] T. März and C.B. Macdonald, “Consistency and stability of closest point iterations,” in prep., 2013. [23] Y.-J. Chen and C.B. Macdonald, “The Closest Point Method and multigrid solvers for elliptic equations on surfaces,” submitted, 2013. [24] M. Attene and C. Pizzi, “Fish,” in the AIM@SHAPE repository http://shapes.aimatshape.net/view.php? id=262, 2005.