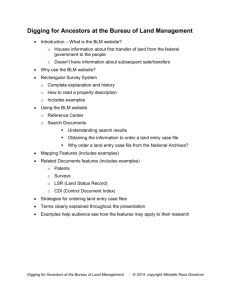

4310-84P DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR Bureau of Land Management

advertisement