IC 1' T-,T fi A1I2TLYTTCAT

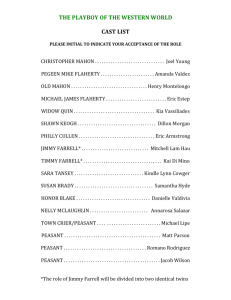

advertisement