wof lIc/s? 19 -'1956

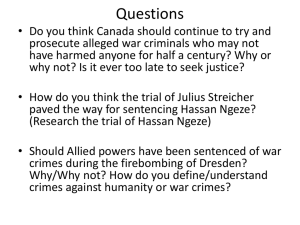

advertisement