by Submitted in partial fulfillment

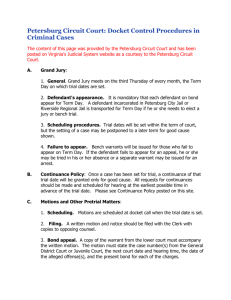

advertisement