1 N

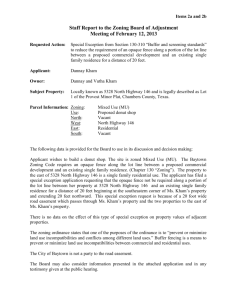

advertisement