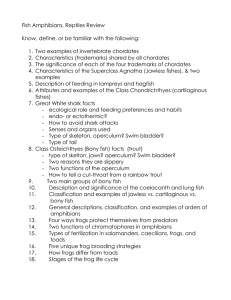

GUIDELINES FOR USE OF LIVE AMPHIBIANS AND REPTILES IN FIELD... LABORATORY RESEARCH

advertisement