MIXED BAG BIG PIC/BACK WHEN • WILDLIFE

advertisement

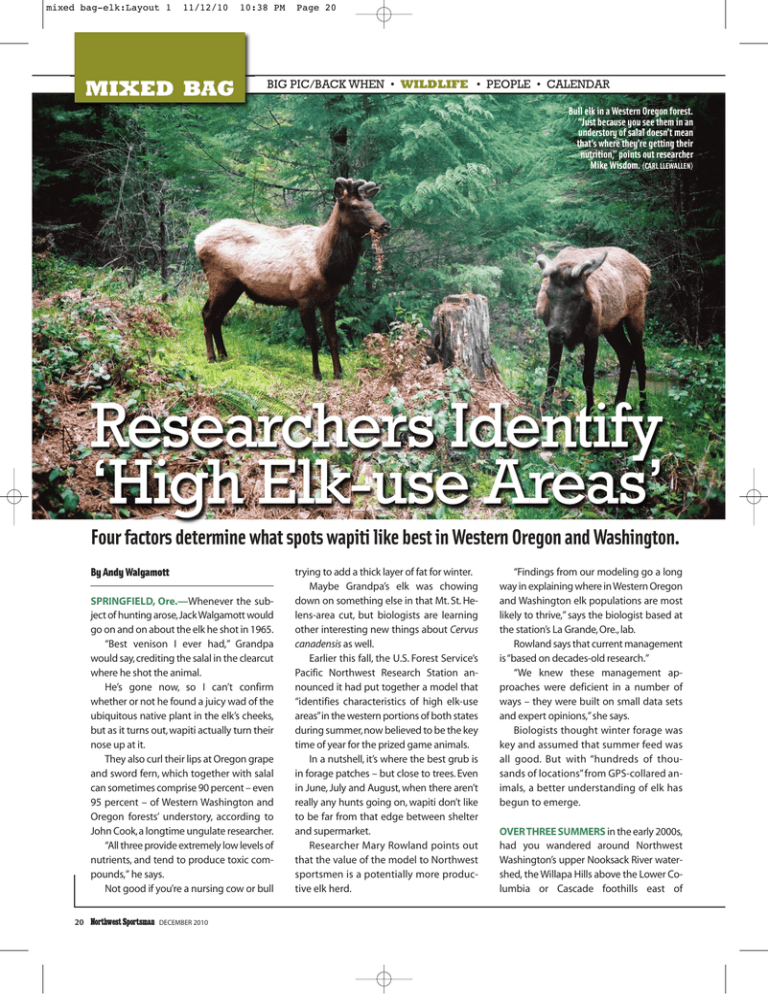

mixed bag-elk:Layout 1 11/12/10 MIXED BAG 10:38 PM Page 20 BIG PIC/BACK WHEN • WILDLIFE • PEOPLE • CALENDAR Bull elk in a Western Oregon forest. “Just because you see them in an understory of salal doesn’t mean that’s where they’re getting their nutrition,” points out researcher Mike Wisdom. (CARL LLEWALLEN) Researchers Identify ‘High Elk-use Areas’ Four factors determine what spots wapiti like best in Western Oregon and Washington. By Andy Walgamott SPRINGFIELD, Ore.—Whenever the subject of hunting arose, Jack Walgamott would go on and on about the elk he shot in 1965. “Best venison I ever had,” Grandpa would say, crediting the salal in the clearcut where he shot the animal. He’s gone now, so I can’t confirm whether or not he found a juicy wad of the ubiquitous native plant in the elk’s cheeks, but as it turns out, wapiti actually turn their nose up at it. They also curl their lips at Oregon grape and sword fern, which together with salal can sometimes comprise 90 percent – even 95 percent – of Western Washington and Oregon forests’ understory, according to John Cook, a longtime ungulate researcher. “All three provide extremely low levels of nutrients, and tend to produce toxic compounds,” he says. Not good if you’re a nursing cow or bull 20 Northwest Sportsman DECEMBER 2010 trying to add a thick layer of fat for winter. Maybe Grandpa’s elk was chowing down on something else in that Mt. St. Helens-area cut, but biologists are learning other interesting new things about Cervus canadensis as well. Earlier this fall, the U.S. Forest Service’s Pacific Northwest Research Station announced it had put together a model that “identifies characteristics of high elk-use areas” in the western portions of both states during summer, now believed to be the key time of year for the prized game animals. In a nutshell, it’s where the best grub is in forage patches – but close to trees. Even in June, July and August, when there aren’t really any hunts going on, wapiti don’t like to be far from that edge between shelter and supermarket. Researcher Mary Rowland points out that the value of the model to Northwest sportsmen is a potentially more productive elk herd. “Findings from our modeling go a long way in explaining where in Western Oregon and Washington elk populations are most likely to thrive,” says the biologist based at the station’s La Grande, Ore., lab. Rowland says that current management is “based on decades-old research.” “We knew these management approaches were deficient in a number of ways – they were built on small data sets and expert opinions,” she says. Biologists thought winter forage was key and assumed that summer feed was all good. But with “hundreds of thousands of locations” from GPS-collared animals, a better understanding of elk has begun to emerge. OVER THREE SUMMERS in the early 2000s, had you wandered around Northwest Washington’s upper Nooksack River watershed, the Willapa Hills above the Lower Columbia or Cascade foothills east of mixed bag-elk:Layout 1 11/12/10 MIXED BAG 10:38 PM BIG PIC • WILDLIFE • CALENDAR • PEOPLE • BACK WHEN Springfield, Ore., you might have come across an unusual sight. A herd of 15 to 20 elk grazed inside enclosures while being watched over by people scrutinizing what the cowcalf pairs were gobbling up. The elk were on loan from the Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife to Cook and his wife and fellow researcher Rachel Cook, both with the National Council for Air and Stream Improvement and also based in La Grande. John says that previous studies show tame elk eat what wild elk would. What they discovered was that the elk really tore into deciduous shrubs like big leaf maple, hazelnut and cascara as well as forbs like false Solomon’s seal. They tolerated most types of grass as well as alder and salmonberry, but avoided not only salal, Oregon grape and sword fern, but also deer fern and most conifers. The work helped develop a nutrition model that predicts “dietary digestible energy,” or DDE. It varies by ecosystem that elk are grazing in, but is a measure of the quality of forage in summer, a key time for bulls, cows and calves to put on the weight that makes them more reproductively fit and better able to shiver through winter. Researchers then used DDE predictions with 50-plus additional factors to check out actual elk habitat use in the Evergreen and Beaver States. That included information from radio- and GPScollared animals in the White, Green and Cedar River basins of Washington’s Central Cascades, and the lower Elwha River on the northern Olympic Peninsula. Four variables that “consistently provided the most support for observed habitat selection patterns of elk” bubbled up. Any guesses? The best grocery stores, for starters, as well as proximity to the nearest open public roads and slope steepness. “Gentler slopes are preferred,” notes Rowland, adding that distance to the nearest cover is a “very strong” consideration. GOVERNMENT AND TRIBAL biologists are testing the habitat model this fall to see 22 Northwest Sportsman DECEMBER 2010 Page 22 cades (13 percent and 95 percent in the Nooksack herd), but those drop sharply as you head towards the coast. Animals around Forks, Wash., and in the Willapa Hills average just 6 percent body fat while pregnancy rates in the Siuslaw and Wynoochee Basins were only 50 and 53 percent. It’s unclear why that is. An easy (JOHN AND RACHEL COOK) answer would be herbicide spraying, but much of the elk-grazing data came from private timberlands that had been dosed to give Doug firs a head start against deciduous shrubs and showed that there was still plenty of good stuff to eat. A better understanding of how chemical applications affect elk and deer browse is needed. Asked their works’ importance to hunters, John Cook responds, “Do you want higher pregnancy rates? Do you want bigger, healthier calves? Do you want yearlings to grow raphow easy it is to apply with their own data. idly? That all happens on the summer Rowland’s fellow PNW researcher and projrange.” ect initiator Mike Wisdom says there were Several Western Washington tribes pro“close matches seen between predicted elk vided elk location data. Oregon State Uniuse from the model and locations of elk in versity is collaborating too. the study areas.” In other words, they say, “The Rocky Mountain Elk Foundation the model is performing well across much has been a huge supporter of this work,” of the region. adds Rowland. “It’s not perfect everywhere, but it Other sportsman groups as well as the works,” Rowland adds. Oregon and Washington Departments of Potentially, the model could be used by Fish and Wildlife have also assisted. federal and state forest managers. There are 3 million acres of Bureau of Land Management and state Department of Forestry land ROWLAND NEXT HOPES to round up in Western Oregon and 1.45 million acres of enough money to send the Cooks and Department of Natural Resources land in ODFW’s herd to Southwest Oregon for anWestern Washington. There’s another 10 other nutrition study. Pointing to differences million acres of national forest in both in the region’s vegetation, she says, “We states, but logging has dropped off sharply don’t think our model is appropriate there.” on that land. She also wants to publish the work in Biologists will be able to make maps that peer-reviewed journals next spring, and the show which areas of the woods offer the modeling team has already begun a similar most forage and what logging or thinning study in the Blue Mountains of Oregon and does for that feed. Washington. “This information can help set goals for As for the all-important question of changing elk use in certain areas and guidwhere the critters go when we’re chasing ing management prescriptions for elk habiafter them ... tat,” says Wisdom. “If we had more time and money, it The Cooks have found that Westside elk would be interesting to continue this with tend to have higher body fat and pregnancy hunting season data,” Rowland says, “but rates the further north you go in the Casthat’s not in the cards right now.” NS This map shows the distribution of DDE, dietary digestible energy – basically, the availability of good (blue) and poor (red) grits for elk – outside of farming areas in Western Oregon and Western Washingon.