20 Fair Chase Summer 2011 n

advertisement

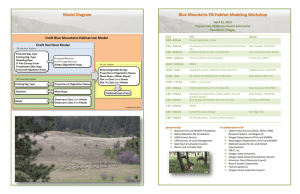

20 n Fair Chase Summer 2011 Elk are one of the most popular game species in North Healthy Forests Restoration Act Mike Wisdom and Marty Vavra have provided valuable insight on new approaches to elk habitat management in western Oregon and Washington, and by inference in much of the rest of elk habitat in the West. This has important implications for maintaining and restoring healthy fire-prone forests. The Healthy Forests Initiative of 2002 and Healthy Forests Restoration Act of 2003 (P.L. 108-148) were implemented by the U.S. Forest Service and BLM on their fire-prone forests and rangelands in the West to reduce hazardous fuels contributing to increasing catastrophic wildfires and to restore fire-adapted ecosystems. Action was taken following a landmark wildfire season in 2000 and dire predictions of future recurrences based on an estimate of about 190 million acres of federal forest and rangeland in the lower forty-eight States with a high risk of large-scale insect or disease epidemics and catastrophic fire due to deteriorating ecosystem health and drought. Data related to Wisdom’s and Vavra’s report show that in drier (“eastside”) forest and rangeland types, the same conditions contributing to increased risks of insect and disease and catastrophic wildfire outbreaks (too much of the wrong kind of plants) are also contributing to declining elk habitat quality (low nutrition quality for cows on summer range.) Improvement of elk habitat quality and restoration of forests and rangelands in these drier ecosystems appear to be compatible and complementary if not compelling goals. We look forward to future reports from Mike and Marty to provide more detail on this important relationship. America. Their widespread occurrence on public lands provides a myriad of public hunting and viewing opportunities. Trophy hunts are now offered for bull elk in every state in the West, and much of this trophy hunting occurs on public lands. But all is not well with elk on public lands. In the past, By Michael Wisdom and elk nutrition on summer range Martin Vavra Ungulate Scientists for the USDA Forest Service was sustained on public forests by Pacific Northwest Research Station extensive timber harvest, which Photos provided by authors opened up forest canopies. The open canopy allowed full sunlight penetration to ground level, in turn promoting vigorous growth of grasses, forbs, and shrubs that established a nutritionally-rich forage base essential to sustaining healthy elk populations. Today, following two decades of limited timber harvest on many federal forests, the abundance of high-quality forage for elk has declined. Federal forest managers scramble to prevent even the smallest forest meadows from being overwhelmed by tree invasion and to maintain their forage productivity, but it is a never-ending battle without active silviculture on the larger areas of forestlands. In response, elk have increasingly sought highly nutritious forage on private forestlands in areas where better forage has been maintained through active timber harvest. Or, alternatively, elk have increasingly sought higher quality forage provided by agricultural lands adjacent to federal forest habitats. Management concerns expressed about elk spending more time on private lands, coupled with the potential for reduced hunting opportunities on federal forests recently provided a strong impetus for new thinking about elk and forest management. These concerns were exemplified by the situation in western Oregon and western Washington. During the 1960s and 1970s, researchers such as Charles Trainer and James Harper, then of the Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife, documented low pregnancy rates, low body fat, and low calf production in westside elk herds. Trainer’s and Harper’s research concluded that the low productivity of westside elk herds was directly related to the low quality of available forage, a characteristic of the unproductive soils of western Oregon and Washington, which are inherently low in nitrogen, calcium, and other nutrients essential to production of nutritious elk forage. Trainer and Harper also reported that the nutritional deficiencies of greatest consequence to elk reproduction and productivity occurred during summer, when lactating females need high-quality forage to successfully rear calves, and when yearlings require high-quality forage for growth and development. Strangely enough, most of the lush understory vegetation present in westside landscapes is unpalatable to elk, and in some cases contains compounds that actually suppress digestion if consumed. The low nutrition levels of the westside, however, appeared to be offset by extensive timber harvest, which provided a more nutritious forage base on forests throughout the region during the 1960s, 1970s, and 1980s. Since then, timber harvest has been halted on most federal forests in the region, leading to the widespread view that elk nutrition has declined dramatically in the absence of continued maintenance of open-canopy, early-seral forests. In addition, private forest owners often accelerate the return of tree cover after timber harvest, shortening the time period in which nutritious forage is available on those lands. Attention to the topic of declining forage conditions for elk on federal forests led to new nutrition research for the species in the westside region in the early 2000s. The research was initiated by John and Rachel Cook, elk nutrition scientists with the National Council for Air and Stream Improvement (NCASI). To understand and quantify the relation between forest management practices and forage conditions, the Cooks used tame elk to estimate the quality of elk diets under a wide variety of forest timber practices and associated conditions. Tame elk, reared from birth by the Cooks at the USDA Forest Service Starkey Experimental Forest and Range near La Grande, Oregon, provided an essential mechanism for the diet work. By following the tame elk over a series of grazing trials in each forest condition (e.g., young stands follow clearcutting, mid-age pole stands, mature stands, Fair Chase Summer 2011 n 21 Tame Elk in Grazing Trial Westside Seral Stages GPS Collared Elk old-growth stands, etc.), the Cooks were able to identify the forage species selected by the elk, and estimate the amount of each forage species eaten. Additional samples of the selected forage species in the elk diets were subsequently analyzed for nutritional quality through laboratory work. Results from the grazing trials and diet quality analyses were dramatic and obvious. Open-canopy forests established immediately after timber harvest, particularly as a result of clear-cutting, resulted in “earlyseral” forest conditions that provided elk with digestible energy that exceeded their daily maintenance needs. All other closedcanopy forests, including old-growth, did not provide adequate amounts of highquality forage sufficient for elk to maintain body fat during summer, a critical time period for elk to accumulate body fat needed for reproduction and survival. “We were astounded at the consistently low quality of available forage under closed-canopy forest conditions in western Oregon and Washington,” said John Cook. “Our findings clearly pointed to the importance of the grass-forb-deciduous shrub stage of succession, following timber harvest, as a critical source of nutrition for elk.” The elk nutrition findings of John and Rachel Cook prompted discussions about new ways of evaluating and managing elk habitat, and the need for new evaluation tools to reflect the new thinking. An earlier elk habitat evaluation model, developed for the westside in the mid-1980s, originally considered elk nutrition as one of four model components, but the nutrition component was ignored by model users. In addition, the model contained a cover component that was later determined to be outdated, based on thermal cover research conducted by the Cooks in the 1990s. Bull elk on U.S. Forest Service land Discussions about the need for new modeling approaches, based on the new nutrition research, were prompted by the leadership of the Boone and Crockett Club and Rocky Mountain Elk Foundation. Said Steve Mealey, vice president of conservation and board member of the Boone and Crockett Club, “Our field visits to national forests in western Oregon clearly showed that the nutritional needs of elk in the region were not being met with current forest management practices, and that land use plans on national forests contained little direction for managing habitat for elk nutrition.” Melissa Simpson, then the undersecretary of agriculture for natural resources, and Jim Caswell, then the director of the Bureau of Land Management, to further identify funding needs and sources. As a result of these efforts, over 20 scientists, representing federal, state, private, university, and tribal partners, began work in 2009 to synthesize and model the findings of the Cooks’ nutrition research in combination with analysis of radio-telemetry data collected during the 1990s and 2000s on wild elk from seven different study areas across western Oregon and Washington. Radio-telemetry data on elk were provided from the seven study areas by the Muckleshoot Indian Tribe, Lower Elwha Klallam Tribe, Makah Nation, Quileute Tribe, Sauk-Suiattle Tribe, and Oregon State University. The synthesis and modeling work had two main objectives: (1) to predict and map elk nutrition across the entire region in relation to all management conditions, encompassing all land ownership areas; and (2) to integrate the nutrition predictions with all other factors that affect elk use of habitat across the region. To meet these objectives, the synthesis and modeling of elk nutrition and radio-telemetry data posed a daunting task that had not been attempted before for elk or other species that range over vast areas. None of the data sets had been collected for such a synthesis, requiring a tremendous amount of time to understand, edit, and integrate the data. Moreover, these data sets required the estimation and mapping of over 50 different types of environmental characteristics, such as slope, aspect, vegetation types, and forest conditions. Such maps had to be developed for vast areas, encompassing many millions of acres of western Oregon and western Washington. And finally, the many radio-telemetry data sets on Management concerns expressed about elk spending more time on private lands, coupled with the potential for reduced hunting opportunities on federal forests recently provided a strong impetus for new thinking about elk and forest management. 22 n Fair Chase Summer 2011 Mealey and Bob Model, past Boone and Crockett Club president and Club board member, joined with Jack Blackwell, then vice president of lands and conservation at the Rocky Mountain Elk Foundation, to organize a series of meetings with state and federal agencies to find funding sources for the new modeling work. Mealey, Model, and Blackwell then facilitated the development of a study plan and grant proposals that led to formation of a team of scientists to initiate the new modeling work. The trio further collaborated on the details of the proposed work with Boone and Crockett Club members wild elk across the region had to be evaluated to assess how well the data could be used to meet objectives. The synthesis and modeling work focused on analyzing the nutrition predictions with the telemetry data, to understand how well elk used areas of highest nutrition, and what other factors, such as motorized access, might inhibit elk use of areas of high nutrition. The modeling work was recently completed, with results that are considered remarkable by elk scientists. In each of the seven study areas where telemetry data were evaluated, elk consistently selected for areas of highest nutrition, particularly when such areas were farther from public roads, on flatter ground, and closer to areas near cover. Remarkably, of over 20 models tested, the same habitat-use model consistently produced the most accurate predictions of elk use across all study areas. The elk nutrition and habitat-use models are now available for management applications. Early uses by federal, state, private, and tribal management partners appear extremely promising in terms of the potential benefits for management. For the first time, nutritional conditions for elk can be accurately mapped across vast areas, and the probability that elk will use these nutritional conditions can be estimated with the habitat-use model that considers nutrition in concert with other major factors that affect elk use. Given the mixed land ownerships in most areas of the region, of particular benefit is the capability to map elk nutrition and habitat use across multiple land ownerships to compare and contrast the probabilities of elk use on private and public lands. Such evaluations allow all landowners, in partnership with state wildlife agencies and conservation groups like Boone and Crockett Club, to discuss and devise ways to effectively manage elk distributions across land ownerships to meet overall objectives for nutrition, population productivity, viewing, and hunting. The developed models predict a need for more early-successional habitats for optimum maintenance of elk herds. Interestingly, a recent article by several noted forest ecologists in the journal Frontiers in Ecology has pointed out the value of early-successional ecosystems that occur following disturbance. These systems were described as providing resources that attract and sustain high species diversity, complex food webs, large nutrient fluxes, and high spatial and structural diversity. The authors concluded that where maintenance of biodiversity is an objective, the importance and value of these earlysuccession ecosystems are underappreciated. The challenge to managers is to develop strategies that effectively provide the structure and composition of these early-succession habitats. Providing improved habitat for elk may, in fact, improve the overall ecological health of westside landscapes. Scientists involved with this new elk modeling would like to expand their approaches to other areas of the western United States for benefit of elk, landowners, and the hunting public. These new modeling approaches also are proposed for development of new evaluation tools for mule deer. Whether this type of innovative work for benefit of elk, mule deer, and other big game species can be sustained depends largely on future support for continued big game research. The key to such future work will be maintaining strong partnerships among federal and state agencies, conservation and hunting organizations, universities, private industry, and tribal nations, as demonstrated by the elk modeling work in western Oregon and Washington. n Drs. Michael Wisdom and Martin Vavra are ungulate scientists with the USDA Forest Service Pacific Northwest Research Station in La Grande, Oregon. They have conducted long-term research on a wide variety of land use issues related to elk, mule deer, and cattle management on forests and rangelands of the western U.S. Fair Chase Summer 2011 n 23