Roosevelt’s Elk: ELK HABITAT SELECTION IN WESTERN OREGON AND WASHINGTON:

advertisement

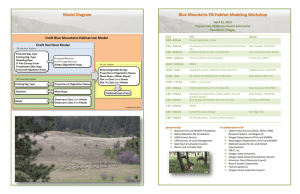

Roosevelt’s Elk: Research ELK HABITAT SELECTION IN WESTERN OREGON AND WASHINGTON: Models for a new century By Mary M. Rowland Wildlife Biologist USDA Forest Service, PNW Research Station La Grande, Oregon 044 ethicsheritage integrity fellowship Elk are big business in western North America, with millions of dollars spent annually on viewing and hunting these magnificent animals. But management of Roosevelt and Rocky Mountain elk in the Pacific Northwest, including direction in federal land management planning documents, has relied for many years on outdated guidelines for elk habitat. Three key reasons justify the need for new information to support updated guidelines: l Elk are highly sought by the public for hunting and viewing – they are a prime recreational resource. l The economic effects of managing for elk are substantial, whether through direct habitat improvements or other costs like those associated with damage hunts for problem herds. l Habitat management for elk is likely to benefit many other native species that depend on early-seral (e.g., grass and shrub) habitats or that are sensitive to human disturbance. First-generation models of elk habitat in the Northwest focused heavily on minimizing effects of human disturbance (like traffic on roads) on elk, but failed to address the limiting effects of specific habitat elements. Declines in elk populations in the 1990s led researchers to pay more attention to these elements, especially summer nutrition, which was previously not considered a problem for elk populations. The last two decades have seen a surge in new research addressing these factors, including elk nutrition. These new studies also reaffirmed the impacts of human disturbance on elk. It was time to put these results to use in new evaluation tools for elk habitat. Enter Mike Wisdom, a research wildlife biologist with the Pacific Northwest (PNW) Research Station of the Forest Service. Wisdom mobilized a team of scientists from state, federal, private, and tribal entities in 2009 to develop and apply new elk nutrition and habitat models for management use in western Oregon and western Washington (“Westside” region - MAP). The project is nearing completion and has incorporated modern modeling techniques to provide a strong foundation for guiding future management direction and habitat restoration for elk. The new models focus on summer range, which is a critical time for elk productivity. The team developed two new models – the first was the elk nutrition model, which then became part of a more comprehensive elk habitat model. The nutrition model predicts dietary digestible energy (DDE) that elk can acquire from each plant community during summer. The predictions from the model are based on diet data collected during years of grazing trials with tame elk across the Westside region, led by ungulate ecologists John and Rachel Cook of the National Council for Air and Stream Improvement. Digestible energy levels in elk diets in summer are affected by the nutritional adequacy of the various vegetation communities used by elk while foraging. Importantly, the DDE levels are related to reproduction and survival of elk in summer and subsequent seasons. This new nutrition model has been applied across the entire Westside region for all land ownerships, based on current conditions, to produce a wall-to-wall map of DDE – the first of its kind. The next step was to integrate the summer nutrition model with several other variables in a “resource selection” modeling process to predict elk habitat use at regional levels. A resource selection model—a special kind of habitat model—estimates the probability of an animal using a particular part of a pre-defined landscape, based on the environmental conditions that most affect or account for landscape use. The model selection process was guided by the expert skills of Ryan Nielson, a biometrician with WEST, Inc., in a complex, iterative process. The team initially considered over 50 traditions fair chase environmental variables related to nutritional, human disturbance, and biophysical conditions, such as distance to nearest water or open roads, slope, and aspect. The scientists then considered subsets of these variables in different combinations to identify which of the many models tested were best supported by patterns of observed elk use, based on radio telemetry locations of elk. To obtain the telemetry data, the team scoured wildlife agencies and Tribal Nations in both Oregon and Washington for such information. The search yielded a variety of data sets, with all but one from Tribal sources. One of the project’s objectives was to build an elk habitat model without spending thousands of dollars putting new radio-collars on elk throughout the Westside, but instead relying on existing radio telemetry data. In the end, usable radio telemetry locations were found in eight areas ranging from the Coquille River in southwestern Oregon to the Nooksack area in north-central Washington. challenge conservation 045 Models for a new century By analyzing the fit between model predictions and elk locations, the scientists were able to determine the top-performing habitat models. These analyses demonstrated that a combination of four variables was consistently and strongly associated with elk locations: l elk dietary digestible energy (higher DDE, higher pre- dicted elk use) l distance to roads open to public access (farther from roads, higher use) l percent slope (flatter slopes, higher use); and l distance to cover-forage edge (closer to edge, higher use). This 4-variable model was head and shoulders above any other combination tested, which was a surprising but welcome result. But answering the next question was even more important – how good a job does this model do in predicting where elk will be in other areas? The modeling team used locations of elk from three of the study areas to build the model, but the true test was application of the model in new areas to evaluate its predictive capability. The remaining five radio telemetry data sets were used for model evaluation. These telemetry data sets were independent of the ones used in the model selection process, an important distinction in a sound scientific process. The 4-variable model performed remarkably well during these tests - the correlation coefficients between predicted use from the model and observed use from elk locations in the five areas ranged from about 0.30 to 0.95 - with most values greater than 0.80. Given that the highest possible correlation is 1.0, the results showed the strength of this model across a variety of diverse landscapes in western Oregon and Washington. “Our results were extremely encouraging, with close matches seen between predicted elk use from the model and locations of elk in the study areas,” said Wisdom. “This information can help set goals for changing elk use in certain areas and guiding management prescriptions for elk habitat.” The model performed most poorly at the very southern reaches of the Westside study area. The modeling team was not surprised – in this corner of Oregon, square in the range of Roosevelt elk, the climate is warmer and the vegetation becomes much more diverse and unlike that of the forests farther north. To address questions raised about the suitability of the Westside model for southwest Oregon and northern California, the Cooks hauled the tame elk around this area for most of the summer of 2011, re- cording what elk ate in different habitats and measuring vegetation in hundreds of plots. These data are now being analyzed to develop a new “variant” of the nutrition model, which will be plugged into the elk habitat model to predict elk use in this area. A key objective of the modeling project sponsors was the creation of management-based tools – not obscure research to be published in scientific journals with little relevance to management. In partnership with land managers and biologists of the Forest Service, Bureau of Land Management, Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife, and Tribal Nations in the Pacific Northwest, the new models were tested with data from a suite of “real life” management scenarios, such as timber thinning projects. This allowed the modeling team to gain users’ perspectives and to obtain constructive feedback about the models and how well they worked for end users. Months of web meetings and conference calls yielded extensive comments and gave the modelers a better understanding of how the models could be applied at a ranger district or regional office level. The modeling results were also shared at two workshops open to the public, held in 2010 and 2011. The modeling team will continue to work with management partners to assist in applying the models on local units and to develop guidelines for best management uses. To recap – what was learned about Roosevelt’s elk populations and habitat? l Elk needs are best met through active management, particu- larly silviculture and fire. Elk benefit substantially from a variety of management practices that reduce overstory cover, but use of the resulting forage depends on managing human disturbance, for example through seasonal road closures. l In general, within our Westside modeling region, the lower the canopy closure and the higher the elevation, the greater the abundance of high quality forage species and dietary digestible energy (DDE). Digestible protein also tends to follow this pattern. l Nutritional resources for elk are relatively poor in the Coast Range and many areas in the Cascades. Even with clearcuts, forage quality is often below maintenance level during summer for lactating elk in these areas. l During summer in western Oregon and Washington, elk select gentle slopes close to cover-forage edges, but away from open roads; consideration of these preferences in planning management activities on public and private lands that sup- port elk is necessary to maximize benefits to elk. l The importance of summer range conditions cannot be underestimated. Forage available to elk during summer directly affects growth of young elk, pregnancy rates of cow elk, and body fat levels of elk entering winter. Consequently, evaluation and management of summer range conditions is essential to year-round management of healthy elk herds. Now that we have these models, what can they do to help elk management? l The new habitat model predicts the probability of elk use across landscapes. The model can be used as the basis for setting goals for changing elk use in certain areas, and to assess how to get more “bang for your buck” with management prescriptions. It can also show the consequences of NOT improving habitat. l Users can compare different management scenarios: for example, using modeling tools that simulate vegetation change, one could “remove” canopy cover in units across a management landscape and then estimate DDE at specific time intervals to make predictions of elk use. If management speeds up or retards vegetation succession, the model will reflect that. l The models are suitable for application across large regional landscapes that cross multiple ownerships and include multiple elk populations. This big-picture approach is designed to help landowners work strategically to integrate management objectives and habitat treatments for elk across ownerships. Management of public lands involves a complex balance between sometimes competing demands. Regardless of the management objectives on a given piece of forest, these new models provide key insights about impacts of different land uses on elk populations and their habitats, and help practitioners weigh possible alternatives. As one workshop participant said, “Having these nutrition maps could really help us from an administrative standpoint because they justify creating openings.” A comprehensive monograph is now being prepared for publication that will ultimately provide the scientific foundation for long-term, credible management use of these new evaluation tools. For those who want more information, a project website has been developed with summary reports and presentations from the two workshops that have been held to demonstrate the modeling results: http://www.fs.fed.us/pnw/calendar/workshop/elk/index.shtml. Acknowledgments The success of the Westside elk habitat modeling project resulted from a diverse array of partners. Key sponsors of the research included the National Fish and Wildlife Foundation, Boone and Crockett Club, Rocky Mountain Elk Foundation, Sporting Conservation Council, the US Forest Service (Pacific Northwest Research Station and Pacific Northwest Region), and Bureau of Land Management. Many other entities contributed data or personnel, including Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife, Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife, the National Council for Air and Stream Improvement, WEST, Inc., Oregon State University, and Oregon State University Extension Service. The project would not have been possible without the help of Tribal nations that provided all of the elk radio telemetry data, with the exception of data from Oregon State University from southern Oregon. Participating Tribes included the Lower Elwha Klallam Tribe, Makah Nation, Muckleshoot Indian Tribe, Quileute Indian Tribe, and Sauk-Suiattle Indian Tribe.